|

ISSUE 6 - MAY 1975

cover size 210 x 148 mm (A5)

EDITORIAL

This is Voices 6, and our total output covers about 300

pages. There have been more than 200 separate pieces in these 6 issues, written

by more than 80 writers, the overwhelming majority of whom have never had work

published previously. The quality varies greatly of course: some of the pieces

(and at this point it would be invidious to select examples) are of high poetic

or literary merit; others are not. The whole purpose of "Voices" is not to

perpetuate mediocrity, but to fan the sparks of imagination and revolt against

what is reactionary, soulless, greedy and exploitative, and to encourage writers

from the factory floor and the branch meeting. We would like world famous

writers, and national figures, and we admire their works in other publications:

but our aim is to help to build a team of working men and women who are

reflecting in new and vivid writing the explosive left movement in Britain and

the world.

We need a lot of help. We are getting new writers with

each issue. Our sales, still modest, are growing. Our financial appeal was

generously backed. But we still do not know whether Labour Party wards, Trade

Union branches, workers in factories, students, Communist Party members, enjoy

"Voices" and feel that it meets a need.

Three of us went recently to a Labour Party group in

Stockport, and read pieces from "Voices" to them and discussed them. There was

genuine appreciation of what we are doing We would like to test the reactions of

all sorts of people to "Voices" and invite you to ask your organization, or

student bodies to give us a chance to explain "Voices" to them.

We need the Labour Movement. Does the Labour Movement

need us? We think it does. Us and organizations and publications like us. We ask

Labour Party and Trade Union and Communist Party, Young Socialist and Student

bodies to help us. How? These are some ways.

Buy a number of copies of "Voices" to distribute and

sell to your members.

Circulate an advertising letter of ours to your members.

Give us a regular subscription (yearly, half-yearly or

quarterly) on which we can rely and budget.

Affiliate to Unity of Arts our parent body, and

contribute an agreed annual affiliation fee.

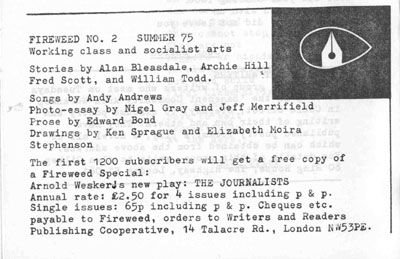

Elsewhere, we welcome "Fireweed" which has an

advertisement of its second issue in the summer. We also give a free

advertisement to "The Basement Writers". We will gladly give publicity to all

ventures which try to establish an association between the Labour Movement and

the arts.

Finally, if among readers living within 10 miles of the

centre of Manchester, there are three or four prepared to give time to helping

to widen the contacts of "Voices" such people can be sure they will be warmly

welcomed.

Our thanks to Peter Carter for the graphics.

Ben Ainley

JOHN MACLEAN

Brian Gallon, 12 Frank Place, North Shields, Tyne and

Wear, is researching material for a play about John Maclean, the Clydeside

socialist leader.

If anyone has personal recollecticns or parents or

grandparents who remember Maclean, or any written material about him, will they

please get in touch with Mr. Gallon.

The cash raised by our appeal in November which finally

raised over £145 helped us clear our debts, and get "Voices 5" out. We are not

out of the wood. It costs around £150 to get out an issue of "Voices" and at

this moment, from the proceeds of sales of "Voices 5" we have around £100. We

are compelled therefore to ask people interested in our survival to continue to

help us financially. We will acknowledge directly all sums received. Make

cheques payable either to Ben Ainley or to Frank Parker.

NOTE TO CONTRIBUTORS

We welcome contributions in prose and verse. But we

cannot undertake to return manuscripts unless stamped addressed envelope is

included.

Number the pages of your contribution. Write your name

and address on each page. If possible, send typescripts; but if your piece is

hand written1 make sure it is legible to the printer.

We are dealing with between 80 and 100 contributions per

issue, and this number is growing. Bear with us if there are delays.

PLEASE TYPE (or WRITE) ON ONE SIDE OF THE PAPER ONLY

This is a must.

A brief personal biography (about 40 words) will help

us, but will not necessarily be published.

|

Reincarnation |

|

|

|

Do you feel misspent |

|

Are you fully content |

|

In the role life's given to

you? |

|

|

|

Do you feel all the while |

|

Something more worthwhile |

|

Is what you should be aiming

to do? |

|

|

|

Do you feel overwrought |

|

At the change change has

brought |

|

In this life by men different

than you? |

|

|

|

Do you just criticise, |

|

Live a life like the flies |

|

And discontent spread like

disease? |

|

|

|

Do you play your part |

|

On the basis of art |

|

Deny what the heart tells you? |

|

At the end of the day |

|

When you get your pay |

|

Do you feel it just isn't

worthwhile? |

|

|

|

Then cor blimey mate, You're

in a helluva state |

|

And there's not going to be a

next time. |

|

|

|

Or |

|

I hope that it's different

next time. |

|

|

|

M.Doyle |

The Christmas Present

The placards screamed the headlines. The evening paper

followed through with the rest of the story.

Citizens homeward bound released from the day's toil,

bought the papers and read the news in shocked silence. "EMINENT NUCLEAR

PHYSICIST RESIGNS".

Professor Lewley withdrawn into the corner of the first

class railway compartment and taking refuge behind a copy of The Times, shook

his head sadly and sighed. Seeing the announcement of his action in the cold

black and white of the placard and stripped of the warmth of his covering

explanation, aroused in him a deep sense of desolation. However, he thought to

himself, staring unseeingly at the small print of the morning's paper, the deed

was now done and the step now taken from which there was no retracing.

He had resigned on a matter of principle and that was

that.

His thoughts went back to that final scene when after

months of grave and gnawing disquiet within himself he had faced his eleven

colleagues on the committee of top level scientists and had delivered the

bombshell. "Gentlemen", he had said, "Brother scientists, after deep and serious

thought on my part I have come to the conclusion that I can no longer reconcile

my own feelings with the aims and objects of this committee for the development

of weapons for use in nuclear warfare.

Please colleagues, I ask you here and now to be good

enough to accept my resignation from this committee."

Looking at the stunned faces of the men around him had

moved him to add softly, "Believe me, I have, as I said, given this matter deep

and serious consideration and I find that now at long last I must face the

realisation that I can no longer work on objects for which the ultimate use will

be the destruction of man, by man."

Of course his resignation had not been accepted

unanimously. Some of the older ones had been prepared to argue it out with him,

make him see reason so to speak, but in the end they too had had to give in,

hoping that perhaps he had been overworking and needed a break for two or three

weeks.

"Why not take a trip over the Xmas holidays,

Lewley old

chap", professor Dacre had said soothingly in a tone suspiciously like that one

would use to a man on the brink of a nervous breakdown. "Just pack a bag and fly

off with your wife and kiddie, say to the Bahamas." "It should be pretty warm

there, just now, I can fix the flight for you old man, no trouble at all, and

you'll get there just in time for the Xmas celebrations." quite an idea y'know."

Lewley shuddered a little, thinking back on Dacre's

patronising air.

Hm! The Xmas celebrations that really was what had

brought things to a head and had determined him to take the final step.

So simple. So utterly, utterly simple, the circumstances

that had at last removed the scales from his eyes and had revealed the image of

his true self, standing clearly before him, face to face.

How often one's puppet sneaks in and takes command,

steering one this way and that whilst one's own soul squeezed out stands by

biding its time just waiting the opportune moment in which to reassert itself.

And so it had been with the learned man of science.

The false premise on which his own sense of security had

rested and which had begun to rock quite some time ago, had finally toppled when

he had been assigned to the role of Santa Claus at the Xmas party of his young

daughter Caroline.

Several of Caroline's little friends were spending the

Xmas holidays abroad with their respective parents and so the Xmas party had

been held three weeks before the holidays.

Dorothy the professor's wife had made up a cloak for him

out of some red cotton fabric, a bit of medical tow had done for the beard and a

furry cap had completely covered his dark brown head. When he had protested at

the too obvious fake of the tow, Dorothy had replied, "Oh the kids'll never

notice, all that interests them is the sack of gifts which you are going to hand

out, after all Caroline and her friends are only five years old."

Then she had added in mock solemn tones,

"I promise you

when Caroline's seven you shall have a full blown grey beard."

When Caroline's seven - sev-en sev-en were his last

thoughts as he drifted off into uneasy slumber that night. "What makes you so

sure Caroline will reach seven?" said his soul, accusingly, confronting him and

barring his way so that he could move neither to the left nor to the right, but

only backwards.

Wildly he tried to press on, but his soul now dressed as

Santa Claus and sporting a full blown grey beard and wearing a mask of the

professor's own features, continued to stand in his way. "Who told you, who told

you?" Frantically the professor looked around for a scapegoat, his eyes large

with apprehension. Then he spotted the tow-bearded Daddy Xmas. Pointing a

forefinger in his direction he cried out desperately,

"He told me, he told me."

The tow-bearded red-cloaked figure advanced towards him, also wearing a mask the

replica of the professor's own features. "Ha, you'd no need to listen to me," he

croaked. "No need at all to listen to me."

"You see", said his soul, gently. "You see!"

"Yes, I see it all now," said the man of science,

dropping swiftly into a relaxed sleep. The way was now clear, the doubts, the

uncertainties, the nagging pointers were stilled once and forever.

And so he had gone forth and given his decision to them.

The decision which by now was being blazoned forth for the world to see and to

wonder at. To be repeated faithfully by some, to be distorted by others.

Dorothy was waiting for him when he arrived home. He

took three large strides towards her and with a tired sigh went straight into

her outstretched arms.

They clung together thus, for a few moments, neither

speaking, each deeply aware of their spiritual oneness.

Then Dorothy looked up at her husband, her eyes shining

as she uttered the words he wanted more than anything to hear from her lips at

this moment. "Don't you see, darling," she said, "You have given those kids the

best Xmas present in the whole world."

Rose Friedman

|

The Quiet Black |

|

|

|

I lay in the darkness looking

at the black |

|

A car past placing a window on

each of the walls. |

|

The clock murmured on and on

always asking the same question |

|

I was uneasy waiting for a

voice that never came. |

|

A tree its branches moving as

a Japanese hand dancer |

|

Formed slowly in half closed

eyes. |

|

Black on a white grey haze,

branches pointing. |

|

Shiny raven branches, carving

twisting in unsettled order |

|

Each offset joint a shape of

beautiful agony |

|

Saying something that I

couldn't hear. |

|

Warm blankets collected my

thoughts |

|

I mumbled prayers in tired

subconscious |

|

Sleep pulled at my eyelids and

the story was left untold. |

|

AM Horne |

|

|

|

A Man in Winter |

|

|

|

I've no flowers for your grave

to-day |

|

So I'll offer my thoughts as a

bouquet. |

|

You remember the clock you

used to wind? |

|

Think of it ... you'll call it

to mind. |

|

It misses the hand that wound

it up |

|

And treated it like a loving

cup. |

|

The roof still leaks, it's not

very strong, |

|

The nights are awful ... awful

long. |

|

My pension was cut when you

went away, |

|

In fact, it was cut the very

same day. |

|

And flowers are dear in the

winter time, |

|

If only we lived in a warmer

clime. |

|

You still haven't got a stone

at your head |

|

My money just goes for rent

and some bread, |

|

And the children don't visit

me any more |

|

Life is harder ... when you're

very poor. |

|

Everyone goes rushing and

tearing about, |

|

Remember old Ted, the way he

did shout? |

|

My old friends have gone ...

all gone away, |

|

Young folk are different ...

nothing to say. |

|

I'm afraid I won't see you

to-morrow, |

|

My dear ... it causes me very

great sorrow. |

|

I'm so shaky now ... I suppose

I'm old |

|

And I walk so slowly and, oh

it's so cold. |

|

The old coat I have so faded

from blue |

|

Lets the wind come tearing

through. |

|

If old Ted were here he'd help

me along, |

|

Young folk are different ...

tho' big and strong. |

|

They just pass me by with

never a glance |

|

For them to speak ... there' s

simply no chance. |

|

Maybe they're thoughtless, the

folk of to-day, |

|

And not unkind as some might

say. |

|

Do you think, dear, that

people do change, |

|

Or is it just me, that's

acting strange? |

|

But, here I am talking in the

wind and the rain, |

|

And all I keep doing is just

to complain. |

|

But, listen to this ... it'll

make you smile, |

|

Yesterday, I walked for nearly

a mile. |

|

I was passing a church, old

and black, |

|

And, thinking of you, went

slowly back. |

|

I went inside and walked all

around, |

|

Apart from my footsteps there

wasn't a sound. |

|

I went so very softly, so

timid and mild, |

|

Right up to a statue of

Madonna and Child. |

|

A candle was burning with

slow, steady flame, |

|

I lit one for you ... and said

softly your name. |

|

I loved you all the days of

your life, |

|

I love you still, oh, my wife. |

|

When summer comes and the

birds are singing, |

|

I'll come every day and I'll

be bringing |

|

Roses of red to show I love

you, |

|

And to make you smile, flowers

of blue. |

|

Your favourite colour ... just

like the skies, |

|

And, oh, I remember ... just

like your eyes. |

|

|

|

Michael Ferns |

|

|

|

|

|

The Gun: Television Gangster

Blues |

|

|

|

Courageous man, he copulates; |

|

He gives to earth the gift |

|

From out his loins: |

|

His living replicas. |

|

His phallic organ |

|

Rejoices in new life. |

|

|

|

Perhaps he has forgotten |

|

The phallic symbol gun, |

|

Shooting out destruction |

|

Into earth's worn womb; |

|

For everyone that he creates |

|

A hundred more shall die. |

|

|

|

For you, for me, O sorry man,

I sigh. |

|

|

|

J McFarlane |

Pseudonyms

F.G. Walker

Father John O'Rourke, small and wiry, was in his study

when the bell rang. He put the silver chalice back in its case and opened the

door. Outside, in the bloom, was a woman. She was tall and

slim like a willow, wearing a dark green suit and a green 'Robin Hood' hat.

"Good evening."

"Good evening. I'm sorry to come so late, but I well, I

was in the district so I thought it would be alright." Her voice had a soft,

light sound, like spring rain.

"I don't believe we've met." She shook her head.

"I'm a writer ... Pat Fielding and I

thought ..."

"Not the Pat Fielding?"

"If you mean the one who wrote 'Tombstones at Midnight'

, yes."

"Well!" He studied her for some moments.

"Perhaps I'd better tell you why I've called."

He stood aside. "You'd better come in then."

She stepped into the light. He closed the door, noting

that she was much younger than he had first thought, and she was quite pretty

too. He led the way to the study; waved her to a chair.

"Thank you." She sank into the seat, sending a

speculative glance around the room.

Father O'Rourke stood across from her, fingering the

soft flesh at the end of his chin.

"You were saying," he said.

"What?" She flicked her eyes back.

"The reason you came."

She smiled lopsidedly. "Well, it might seem silly really

but I've just started my next book and I'm trying to ..." She paused,

gesticulating with one hand. "How shall I put it ... trying to get the right ...

atmosphere." Her voice rose on the last word.

"I see." His eyes narrowed. "This new book. Is it

anything like the last one?"

"You've read it?" She lifted her eyebrows a little.

"Yes, twice as a matter of fact."

"I'm flattered. I hope you'll buy the new one." He

shrugged. There was a small silence. An idea flickered in his brain. "Perhaps I

could offer you a glass of sherry?"

"Yes, thank you."

He went over to the sideboard and poured one glass of

sherry.

"Look," he said then, "I have to make a phone call, I won't be a

minute." He went through to the hallway, made the call and then padded outside

into the drive. Her car was turned round, facing the road. He wondered what she

was doing here. Then he laughed softly. He opened the car door and took the

ignition key. Then he went back to the study.

"May I look round the church tonight?" The woman stood

up as he entered.

"I suppose so ... if you're not frightened."

"You'll tell me it's haunted next."

He held the door open and waited while she picked up her

handbag. As they went out he said: "I suppose I'll be in your book?"

"Perhaps." She stopped; gave him a quick look from under

her dark lashes, then she added: "In fact it might be a good idea."

"You haven't decided then?" She tilted her head on one side.

"It depends on the

story ... and the atmosphere. Shall we go?"

"Sure." He led the way across to the church; pushed open

the door. "What would you like to see?"

"The belfry." She sounded as if she had been expecting

the question. He turned left into the small alcove that led to the

stone steps. Looking back at her, he said casually,

"They say a ghostly monk has

been seen hereabouts." She stiffened visibly.

"Oh! Really?" Her voice trembled.

"Where ... exactly?"

"Here. Still want to go up?" She looked at him for several long seconds.

"Yes." He started up the narrow winding stairs. At the top he

unbolted a small trapdoor and climbed through. He turned, looking down at her. She stayed there, her head and shoulders through the

opening. A little breathlessly she said:

"Are we alone now?"

"Of course." He stepped back. "Come on up." A smile pulled at her lips. She reached up; grabbed the

trapdoor.

"Sorry Father. But I've made other plans. She pulled down the trapdoor then and slipped home the

bolt. With a laugh that echoed on the stairs she hurried away. He knelt down; tugged at the handle. It held fast. He

stood upright, breathing hard. Then he remembered the torch in his pocket. He

rushed over to the wall and stared hard at the darkness. Twin headlights pierced

the night on the main road. He almost laughed out loud as he began flashing the

torch.

The police car swept up to the church. Two minutes later

he heard the bolt drawn on the trapdoor. A burly constable led the way down into

the church and across to the vestry.

"We caught her, sir," he boomed. "Trying to start her

car." He swept open the study door.

Father O'Rourke blinked at the brightness. In a chair

near his desk sat the woman. Her face was the colour of raw cod. A police

sergeant towered over her.

"Caught her with this, sir," he said. He indicated the

silver chalice on the desk. "If the car had started she'd have got away with

it." Father O'Rourke smiled impishly. He took the ignition

key from his pocket; tossed it on to the desk.

"I made sure that she wouldn't,"

he said. The woman jerked her head up; for a second her eyes

blazed.

"You ... you... How did you know about me?"

"Simple." He spread his hands, as if that one -gesture

was sufficient. There was a tiny silence.It was almost as if, from across the room, he felt her

wince. The police sergeant rubbed thoughtfully at his chin. Father O'Rourke sauntered across to a book case,

selected a volume and handed it to the woman.

"Perhaps you'd like to read this,"

he said in a soft whimsical voice.

She gazed at it curiously. It was encased in a brightly

coloured dust cover. Her eyes lingered on the words: "A NEW NOVEL BY PAT

FIELDING." She turned the book over, and on the back was a picture of Father

O'Rourke.

|

The bell spews its evil |

|

|

|

The bell spews its evil and

the leash is slipped, |

|

you're washed, your gear's

gathered |

|

and you sail like a pigeon

into the clean fresh air |

|

circling through the scent of

honeysuckle that isn't there |

|

flying up up into the bright

sky until the sunlight hurts your eyes |

|

then you come to rest upon the

gentle, rose scented waters of melancholy |

|

until the leashes of necessity

and conformity drag you back next morning. |

|

|

|

Jimmy Barnes |

|

|

|

|

|

The Name of the Game |

|

|

|

People like us |

|

can be very mean |

|

until we learn |

|

the name of the game. |

|

|

|

Blame if you must the blacks |

|

for the squalor we live in, |

|

for our depreciated |

|

standard of living, |

|

|

|

but who gains most |

|

from lack of houses, |

|

whose profits are swollen |

|

with stolen wages? |

|

|

|

Mean we shall remain |

|

until we learn |

|

the name of the game |

|

is money. |

|

|

|

Bill Eburn |

|

|

|

|

|

Harry the Tick Man |

|

|

|

Harry comes on Fridays,

paydays |

|

Round the doors in his estate

car |

|

Holding back the revolution

singlehanded |

|

Outfits for you and your man

for the club dance |

|

Fifty pence a week, no

deposit, no bother. |

|

|

|

He carries an armload of lurex

dresses |

|

Cheap tinsel, wherever he goes |

|

In case some one's in need |

|

The car is bulging with

cellophaned sheets |

|

Shoes and boots, jeans and pit

shirts |

|

All new, all in a jumble. |

|

|

|

Working late for village

Cinderellas |

|

Swopping shift money for

weekend dreams |

|

No deposit, no bother. |

|

|

|

Vivien Leslie |

|

|

|

|

|

Staunch, true Comrade |

|

|

|

Staunch, true Comrade |

|

it hurts to see you |

|

suffer for your belief. |

|

You are ready to fight |

|

for a world that seems lost. |

|

You swim against the tide |

|

waving your convictions |

|

like a banner |

|

while others run and hide |

|

wrapped in their cocoon |

|

of complacency |

|

fed on glib promises |

|

and poisoned by subtle

tongues |

|

against you. |

|

Your courage shines like a

beacon |

|

A light in a dark world. |

|

|

|

Jean Sutton |

|

|

|

|

|

Factory Boy |

|

|

|

Went to school, got no joy - |

|

Where's your school uniform,

boy?" |

|

Messed around, broke up

chairs, |

|

Smoked fags under the stairs. |

|

|

|

Got a job on the assembly

line |

|

Same bloody thing all the

time. |

|

Look forward to Fridays - at

the pub scene. |

|

At the match on Saturdays -

let off some steam. |

|

|

|

Born into this mess, never had

a hope, |

|

Too many kids, me mum couldn't

cope. |

|

Too noisy and crowded at home,

same at school; |

|

No wonder I broke the rules! |

|

|

|

Me mum just watches the tele, |

|

Me dad's always on the drink. |

|

And you wonder why we go on

strike, |

|

The system that causes this

stinks. |

|

|

|

I'm the stool the middle class

sit on, |

|

I'm the tool the middle class

shit on. |

|

But one day - you wait and

see, |

|

We'll run our factory; me

mates and me. |

|

|

|

Oppression |

|

|

|

Oppression... |

|

Corruption... |

|

|

|

Depression... |

|

Disruption... |

|

|

|

Eruption. |

|

Solution? |

|

|

|

Revolution! |

|

|

|

Tony

Harcup of the Basement Writers |

A number of comments follow on the article by Ken Clay

which appeared in Voices 5:

Of course there is a tendency for new, dedicated,

enthusiastic working class writers to write in the way he deplores, but I think

if they are sincere, and not just striving for effect, or to convert, they'll

learn to be artistic as well as realistic.

There is also a technique of writing which does not come

easily or naturally to people whose vocabulary has already been limited by the

so-called examples of culture around us. Small wonder they overdo things, when

they write themselves, like teenagers who must be fashionable, even if it hurts.

Finally, if we are sincere, we too must strive to be

encouraging, as well as critical, both of ourselves as well as fellow writers -

God knows the unpublished, unknown, writer has enough to contend with, when

trying to get somebody to read his work, and there must be many who remain dumb

through lack of opportunity or hope. This is where VOICES CAN HELP, by making

people more articulate, and perhaps eventually more observant, analytical,

critical, and discerning too.

W. Froom

Would Ken Clay perhaps have modified his schoolmasterly

rudeness if he had thought his letter would be printed? Talk about didactic? Of

course it is often hard to avoid sounding bossy if we lay down the law,

especially to those who don't accept our ideas.

People write out of their experience of life; often it

is a hurt that sets us composing. Capitalism is a system that crushes and hurts

us and we cry out. Our one sidedness is usually too much doom and gloom and we

are embarrassed when we celebrate the joys of life, but that too is real, and

genuine experience. Why should those of us who are happy in love be called

dreamers for example? As for style, people write as they have learnt, and only

in relation with others do they modify and refine in their own way the common

heritage - which of course is part of bourgeois culture - but are we to stop

speaking in case we are bourgeois? It is not the words we use, it's what we say

that makes us different.

The fashion is to be opaque, of course, and such a style

is great fun to write; but are we writing to show off or to communicate? In

years of reading poetry (not just my own) to ordinary people I for one have had

to make a choice. If art is communication, as I believe, and if we want to talk

to people, we must talk in common ways. But not in watered down English or in

bad language. The Labour Movement taught me that long ago.

Finally, how intolerant can you be? The infinite variety

of personality offers many ways and styles of writing. There is more than one

'right' way. The thing, surely, is the affirmation of belief and confidence in

people, and the refusal to accept misery as our lot.

As for me, I have lived as an active communist for forty

years, and must write out of such an experience subconsciously by now.

Frances Moore

I find it a matter of urgency

to make a reply to the

article about "Voices" written by Ken Clay. I hope you can find room in your

next issue to publish this.

The main error in his article is his definition of

Socialist Realism, Socialist Realism is NOT "A discipline designed to produce

parables rather than art." That may be Ken's definition, I suspect Ken has

mistaken the crude "banner waving" material that does at times appear in

"Voices" for a definition of Socialist Realism, if so, he couldn't be farther

off the mark. The discussion that really remains is: What is "Socialist

Realism"?

How many conflicting ideas emerge, basically ranging

from those who never seem to have shaken off their respect for bourgeois ideas,

hence they do produce these abstract, complex, over-worded symphonies of

literature that Ken mentions.

Then the other extreme is the growing idea that any

crudely rhyming, "Red Banner" waving wordiology, however crude it is in form

(sometimes the cruder the better) in fact anything written by a worker

constitutes "Workers' art": therefore if it waves aloft the red flag that is

"Socialist Realism".

This form of diversity will I think be inevitable in any

left wing movement of the arts such as "Voices" which is trying to counter

bourgeois publications, and I think it will be some time before Socialist

Realism in the western movement really emerges.

Anyone in contact with present publications from the

Socialist Countries (Soviet literature etc.) will see the results of past

struggle, the emergence of Real Socialist Realism.

Socialist Realism in my definition is art conscious of

its role in Society. An art having something progressive to contribute, an art

based on all aspects of humanity, progress and beauty. Art should uplift,

agitate, enlighten, educate and give the reader a greater understanding of his

relationship with his fellow man, nature, society, love and the ever present

riddle of infinity, but must always retain some aesthetic quality.

Poetry is a medium of expressing ideas, thoughts,

feelings etc. that cannot be expressed in any prose. If prose could cover these

manifestations fully Poetry would never exist, therefore Form is important as a

medium of creating in the reader the emotions that the writer intended.

Socialist Realism strives to create positive emotions and reactions to the world

around us. The worker who is talented and has something to say, will, with

effort, defeat all the obstructions that lack of decent education present to

him.

Oversimplicity, crudeness and "banner waving" (The

glorious working class marching sternly forward etc.) is not only unreal because

it is most often not the case, it also lacks humanity and didn't Marx call

Communism "Scientific humanism"? Also it can tend to embarrass the audience.

Over-complexity tends to often cover subjectiveness and tends to overawe the

audience.

Our job is not to create a "sub-culture" but real

Socialist culture of the very best. The idea that any worker who picks up a pen

and scribbles a few words is a proletarian artist is false and often comes from

the middle class. Bringing culture to and out of the working class is a

challenge, but not impossible.

By supporting "Voices" we can help this process, so let

us throw our words at one another and the world for the sake of humanity.

Fraternally, Ian E Reed

To Instruct or Delight?

1. "He will win universal applause who blends what is

improving with what is pleasing, and both delights and instructs the reader"

wrote, Horace, which does rather suggest the problem is not altogether new. Ken

Clay would doubtless like Voices to do both. The question is how.

2. Things to avoid according to Ken

(a) Didacticism - many of us feel there is not much

point in writing unless you have an audience; some of us go further and consider

there is not much point in having an audience unless you give them the works.

Too true. How many of us have lost friends that way?

(b) Social realism - this seems to me to be an extension

of the above except that to the sin of proselytising is added the further sin of

over simplifying. Capitalists wear black hats, communists white ones. To this

too some of us must plead guilty.

(c) Naive idealism - Ken seems to be suggesting that

even if people like us have something to say they don't say it because they feel

inhibited, and tend instead to ape their betters. One reason for this might be

that Voices is unique. Other journals won't publish unless the contributor

sticks to the rules.

3. What is to be done then? Or, to put it another way,

what would I do if I were a member of the Editorial Board?

(a) I would accept with gratitude any contributions

which both delighted and instructed, although one could expect these to be few

in number. Blake, Byron and Shelley, and say Siegfried Sassoon in his anti-war

poems, could do it; but most of us are learning the hard way.

(b) The rest I would select according to whether they

delighted or instructed, though I would expect Voices to have a bias in favour

of the latter. There are enough glossy journals that serve to please.

(c) Those that appeared to fall into neither category

would have to be returned to sender, though I would like to think that someone

would be able to find the time to return them with a word of encouragement.

There is no point in our persuading ourselves there is a vast amount of talent

available unless we do our best to use it.

4. Ken may well think that my response raises more

problems than it solves. e.g. what do we mean by "instruct" and "delight"? Well

I'm not greedy. Let someone else have a go.

Bill Eburn

|

The Silly Bloody Working

Class |

|

|

|

Who builds the bridges and the

'planes |

|

Who builds the ships and all

the trains |

|

Who builds the roads and sleek

fast cars |

|

Who are slaughtered in their

masters' wars |

|

Who wander homeless in every

nation |

|

Whilst editors express their

jubilation |

|

At the jumping stocks and

shares |

|

Whilst pensioners starve and

no one cares. |

|

And who the fools that endure

all this, alas, |

|

The silly, bloody working

class. |

|

Who sweats and groans and

grows old fast |

|

Who suffers and moans and at

the last |

|

Are led like beasts to grim

old places |

|

To sit and sigh at unknown

faces. |

|

Whilat politicians lie in beds |

|

Making up speeches about the

Reds. |

|

Who forms the queues outside

the dole |

|

Who in history has the role |

|

Of saving all, except

themselves, alas, |

|

The silly, bloody working

class. |

|

|

|

Michael Ferns |

Modern Poetry, Eliot and the Working Class

Does the modern poet write for the working class, or for

fellow poets and critics? I'm afraid it is not the former. It is not that poetry

is not easily available to the working class - it is. Its insularity derives

from its esoterical lineage and its erudite- ness. A poet, such as Eliot, has so

many cross references (what working class man hears of Webster, or St. John of

the Cross?) that the poetry can become like a Times crossword puzzle -

interesting, taxing but pointless.

One can't help feeling that Eliot can only be

appreciated by someone with a similar education to his own (remembering that he

was at school until his mid-twenties). Obviously, he can only write of his

background, his class, and the preoccupations of his class. The truth of the

matter is that Eliot writes for poets; for a man to understand him, he must

raise himself to the level of a poet. Which isn't a bad thing, but hardly

feasible considering the circumstances of most people. To use one of Eliot's own

phrases - "there is no objective correlative common to the rich Oxford educated

banker, and the ill educated capstan lathe operator."

Poetry can only become truly modern, when it can live as

the expression of a struggle to raise our conscious mind to a greater level of

awareness. What has gone before in poetry has been the expression of a small

minority of people's reaction to the universe and society, the greater part of

humanity's feelings going unverbalised. It has been played like a game for the

elite, with a strict, almost impenetrable code of conduct. It has been preserved

like a Ming Vase, for all eternity - daring imitation or improvement.

Poetry should be written, digested and thrown away for

practical purposes. Art is of its time, created from its time, by people who

will take the rein of history and guide it. Do we need this over-indulgence in

past expression, expressing what has gone is dead?

A people has its creative wellspring, and only when we

become involved in history, will the poetry flow. When we awake to the modern

situation, we will get modern poetry; and what poetry does a line of machines

inspire?

Real modern poetry will only come through an honest

survey of the situation. Eliot represents decadence, art for the liberation of

the individual, He is not concerned for the rest of humanity, other than the

rich, or gifted.

A modern poet will realise his purpose and function. It

will not be to give the dilettante something to prattle on about; or to furnish

material for the professors to write exegesis. It will be to reflect, consider

and direct the mass of people now ready to break in on history. To give them a

mirror on themselves, and a fresh language to express their struggle.

Poetry has become the activity of the few for the few.

It still is the poetry of unconnected individual destiny with an unhealthy

preoccupation with self. Even poetry of rebellion - say Baudelaire or Rimbaud is

put into a snug system, its shock value eliminated by careful study.

The truth has to be retold by each generation to itself.

Reality has to be re-examined in the light of our total experience, which is

different from generation to generation.

If we are the lost children of god, alone without a

faith, we should not waste time looking for our lost father as Eliot does. We

should look to find ourselves, and poetry must be of this struggle, not of lone

individuals' search for the absolute.

Tony Whitfield

|

Poetry Where Are You Now? |

|

|

|

Poetry; Daughter of

inspiration and love, |

|

where are you now in England? |

|

Are you now drowned in

intellectual blood, |

|

has your body been ravished |

|

and drowned by the flood? |

|

Smashed into formless

phantoms? |

|

|

|

Poetry; Mother of rebellion

and hope, |

|

where are you now in England? |

|

Have bandits of words now

tethered your scope |

|

to meaningless rantings? |

|

Now in darkness to grope |

|

in their minds empty spaces. |

|

|

|

Poetry; Lover of freedom and

truth, |

|

where are you now in England? |

|

ravished by demons both base

and uncouth, |

|

with no direction to roam |

|

your torn body a proof |

|

of dignified killers still

prowling. |

|

|

|

Ian E. Reed |

|

|

|

A Matter of Opinion |

|

|

|

He came to the village

brandishing wall charts |

|

Equipped with degrees and

graphs |

|

He lectured on social change

and evolution |

|

He stood his reasons up in

rows |

|

And argued with himself |

|

To make his lack of prejudice

apparent |

|

Out of the crowd came a

demanding shout |

|

"Think yer clever, eh? Name me

three early tatties!" |

|

|

|

Vivien Leslie |

|

|

|

Remember Your Kerb Drill |

|

|

|

Stephanie |

|

Wait for me |

|

Stand still |

|

Remember your Kerb Drill |

|

Open your eyes |

|

It's not just a prayer. |

|

|

|

Look right |

|

Look left |

|

And Look right again |

|

And Look left again! |

|

And Look right again! |

|

And Look left again! |

|

And... |

|

|

|

Wimbledon has nothing |

|

on this |

|

At last a gap |

|

Run across as fast |

|

as your little legs |

|

can carry you |

|

Do not trip! |

|

They cannot stop |

|

They are not |

|

Niggers or hippies |

|

or old age pensioners |

|

but good solid |

|

First Class citizens |

|

who do not |

|

have to wait |

|

respectfully |

|

at the kerb. |

|

|

|

Alan Prior |

|

|

|

|

|

We

came en masse |

|

|

|

We came en masse |

|

To cheer you in your hospital

bed |

|

complete with gifts |

|

and smiling faces, |

|

grouped round your clean

clinical bed |

|

a mission of love |

|

with one eye on the clock. |

|

|

|

And then you took the stage |

|

and held us spellbound, |

|

words and pictures tumbled |

|

from your lips. |

|

Heads turned round |

|

and smiled to see us

laughing, |

|

though they could not hear |

|

your droll and merry quips. |

|

|

|

You warmed us, |

|

we who had come to comfort |

|

and to cheer. |

|

And when we left |

|

turning to wave at the door |

|

we saw your smiling face |

|

and took you with us |

|

-somehow, we did not leave

you |

|

lying there. |

|

|

|

Jean Sutton |

|

|

|

On Winter's Highway |

|

|

|

Through a haze of driving

rain |

|

the distant hills are bleak

and grey. |

|

Wind, cold, gusty, gaunt,

flaps the rain like blankets |

|

pinned against the sky, |

|

then slaps the backs of

animals as they stand, miserable, patient. |

|

|

|

The fields, full-flooded

lakes, feed the ditches and the roads, |

|

drowning all life. |

|

|

|

All his darts thrown, |

|

the wind staggers, falls,

feebly struggles. |

|

The rain, his former

plaything, now gently covers him. |

|

Suddenly the clouds break, a

javelin of light flames through, |

|

touches the hills on the

instant, for man to see |

|

all his hopes and yes, his

immortality. |

|

|

|

AG Froome |

|

|

|

|

|

Saving

Face |

|

|

|

The Pound, my son, is best of

friends, |

|

which in thy pocket dwells, |

|

In two score years and inure,

I've proved, |

|

No lie my Father tells, |

|

Whilst pride of place, the

cash to save, |

|

He gave his full attention, |

|

There's saving, other, I've

learned dear Father |

|

Than cash to merit mention. |

|

|

|

The life-boat crew, whilst

battling through |

|

the storm think not of

earning, |

|

Or the fireman bold, when

flames enfold, |

|

Some helpless victim burning, |

|

The Surgeon's skill with

scalpel, will |

|

Great numbers save from dying, |

|

Each course they choose, at

times may lose, |

|

None count the cost of trying. |

|

|

|

Although we toast this

numerous host, |

|

And others, who us do favour, |

|

Unlike these deeds, among us,

breeds, |

|

Another form of saver, |

|

Whose fellow man, he'd trample

down, |

|

That he himself may climb, |

|

Would soul deprave, his face

to save, |

|

It's the ultimate, untried

crime. |

|

|

|

This Predator, in peace and

war, |

|

To no one land peculiar, |

|

Would he in Hell be better

placed? |

|

He's surely nature's failure? |

|

The death he's planned, while

in command, |

|

Some died without a trace, |

|

what thousands yet will die to

save? |

|

Some Politician's face? |

|

|

|

Will he, in anger with his

finger? |

|

Press the button we cannot

stop, |

|

All life disgrace, whilst

saving face, |

|

We can only wait and hope, |

|

That while there's time, men

will combine |

|

With Charity and Worth, |

|

No privilege crave, but just

to save, |

|

The face of Planet Earth. |

|

|

|

Alexander Jamieson |

|

|

|

Turning Point |

|

|

|

Liggin' together o't' th'after, |

|

We talked o' thi mam. |

|

Aw'd said, |

|

Mindin' 'er gabbin' an'

laughter, |

|

It wur 'ard t'insense, as

hoo'r dead. |

|

An aw rued hoo couldn't ha'

known |

|

Ut, tho' yo'n parted, 'im an'

thee, |

|

T' feelin's twixt us a' t'

while 'ad grown: |

|

Ut sum'dy luv'd thee - an'

theaw me. |

|

But, at t'moment, aw'r some

an' ta'en |

|

Aback, as tha nestled to lay |

|

Thi yed o' mi shou'der - an'

then, |

|

She'll know now, though", aw

yeard thee say: |

|

An' so tha wept |

|

Afoore tha slept. |

|

We're nooan o' t' same mind o'

this'n, |

|

Us two; for me it's 'ard to

grasp |

|

One meht lam an' look an'

listen |

|

Who's nobbut neaw yepsintle

ass. |

|

Beside which, t' thowt one

meht ha' sin |

|

Us bally-to-bally jus' neaw |

|

a rude sort of intrusion in |

|

Ear lowly luv-o'er-t'latch,

chuseheaw. |

|

Thi breathin' steady wur good

t'hark, |

|

Whilst t' sliftert city neet-sky

leet |

|

Thwittled thi beauty eawt o'

t' dark |

|

So's gazin', fond, aw'r fain

to see't: |

|

An' aw c'd own |

|

Aw'r nooan alone. |

|

|

|

Bu' t' neet-lang shadder fancy

- yearnsfu' to compensate |

|

for t' mischance o' t' toom

moment when aw'd failed to relate - |

|

proved nooan jannock bi t'

dawn leet, an' ony rooad to' late: |

|

frae't let-deawn - reet that

moment - thy luv wur set t'abate. |

|

|

|

Jone o' Broonlea |

GLOSSARY - Turning Point by Jone o' Broonlea

Insense - realise. Some-an' - very much. Yepsintle ass -

a small amount ("handful") of ash. Meht ha' sin - might have seen. Sliftert -

enter through a crack. Thwittled - carved. Fain - glad. Own - admit. Toom -

empty. Jannock - genuine.

The Housewife

"Dear God, another day! What was it? - Tuesday, Oh yes,

stairs and hall and mince-meat stew." Already the morning was slipping by. The

pots waited; silently sneering under a blanket of egg-yolk and toast crusts.

They should have been washed long ago, still, she promised herself that she

would do them as soon as she had had another cup of tea.

She wandered over to the kettle, her image curving down

its side, like the walls of the house around her throat. Icily she picked up the

baby's rusk and put it into her mouth. She hadn't even realised what she had

done until angry screams of annoyance met her half-closed ears. "Sorry chicken,"

she thought, too tired and distant to speak, and placed it back into her child's

mouth. She lifted her hand to ruffle his hair but accidentally knocked his cheek

with water-worn hands, heavy with boredom and hidden despair.

Plugging in the kettle she thought about how she had

found her ring in last night's hot-pot. Should she tell her husband and make him

laugh like she used to? Searching in her mind for the answer she realised she

didn't even know how to talk to him any more; besides he probably couldn't

remember her losing it. She put the thought out of her mind. It was too much

trouble worrying over words. The pots grew in number. The electricity ran out

and the kettle murmured to a halt. She went to sit down, tired out from

thinking. Scared of thinking.

Rosslyn O'Connor

Fireweed

A warm welcome to "Fireweed" announced as a quarterly

magazine of working class and socialist arts, beautifully designed and printed,

copiously illustrated, and with a dozen distinguished contributors, including

the world-famous Bertolt Brecht and Pablo Neruda. If this level can be

maintained, "Fireweed" will be that "flowering weed that spreads across waste

land" which is the meaning of its title.

For the most part it is a fine compilation, and if this

reviewer expresses his preferences, for the world-famous Neruda and Brecht, for

Archie Hill's unbearably tragic story of a boy's first day at the foundry, for

David Craig's poems of crofters, for the extract from Margaret Parkinson's

novel, and for Leon Rosselson's magnificent folk ballads, others may well find

matter for pleasure in other contributions.

It is said to be a brave venture to launch a magazine

like this in these difficult days. But when the old world is visibly collapsing

before our eyes, when revolutionary ferment and change is seen on every

continent, among millions of people, the need for art to give confident

expression, imaginative creative expression to it, to open up for hitherto

silent man and women a medium in which they can speak for themselves, is very

urgent.

Elsewhere "Voices" carries an advertisement of Fireweed

No. 2 which will appear in the summer, and this promises to maintain the present

level. "Voices" which carries no national names, and whose writers are so far

unknown, sees in "Fireweed" a colleague and a co-worker, and we hope to be of

mutual assistance in the future. Trade Unions, Labour Party, Communist Party and

the host of people who both love the arts and work for socialism and peace,

should give "Fireweed" active support.

Ben Ainley

|

|

|

Listen to the Old Men |

|

|

|

Listen to the old men cry the

pity |

|

Remember remember remember to

weep |

|

Remember to breathe in long

and deep |

|

The smell of grass burning in

the city. |

|

|

|

Balcony railing scrapes shins

unused to climbing |

|

Bloodstain like ink on

blotting paper |

|

Spreads downwards and outwards

on nylon stocking |

|

Tears mingle at corners of

mouth with desperate |

|

saliva |

|

Red scrabbling furious hands |

|

Scratch at brickwork |

|

Grasp at stanchion |

|

In vain |

|

The final irony |

|

Not to jump but to fall |

|

Like the first autumn acorn |

|

|

|

Ten storeys she plunges |

|

Breath forced out of tortured

lungs |

|

Screeches like the death cry

of a train |

|

Entering a tunnel |

|

Turning on a bedroom light on

each floor as she passes |

|

Finally explodes blood and

brains |

|

Like a water bag on the

concrete car park |

|

The new curtains just would

not fit |

|

|

|

Ten storeys' worth of women

send ten storeys' worth of children |

|

To bed and weep |

|

Ten storeys' worth of men make

love to the women |

|

Below on the adjoining half

finished block |

|

The old night watchman throws

an empty soup can |

|

At a mongrel peeing on the

cement bags |

|

On the ninth floor a woman

stretches to put up new curtains |

|

|

|

Smell of grass burning in the

city. |

|

|

|

Alan Arnison |

|

|

|

|

|

Woman's Paper |

|

|

|

Comment upon this whore's

exchange |

|

On methods how to get your

man? |

|

Sales talk on an accepted

range |

|

packeted to a streamlined

plan. |

|

|

|

Protuberance of breast and bum |

|

Permitted but of belly barred

- |

|

Hogarth's exuberance become |

|

Vulgar and therefore off the

card. |

|

|

|

More mealymouthed less glossy

page - |

|

That gives the little woman

hints |

|

On what attractions will

engage |

|

And hold her worker between

stints. |

|

|

|

Intellectuals display |

|

Unmealymouthed and without

ruth |

|

Their wares in the same brazen

way |

|

Tricked out with scientific

truth. |

|

|

|

If you accept the woman's

place |

|

As brood mare, lollipop and

drudge, |

|

Here's how to prosper in that

race, |

|

But here's no relevance to

love. |

|

|

|

Frances Moore |

|

|

|

|

|

Promise |

|

|

|

Those who are ossified

themselves in mind |

|

And therefore also calcified

of heart, |

|

Postulate natural laws that

bind |

|

All of us to as limited a

part. |

|

|

|

When we first start to notice

on our face |

|

Wrinkles begin to annotate the

years, |

|

We hold our peace about our

passion's pace |

|

Lest we provoke the ignorant

to jeers. |

|

|

|

But lay it to your heart for

coming time, |

|

Love's possibilities are not

laid down |

|

By armchair pedants bent on

tidying life. |

|

Middle age modulates new joys

to crown |

|

Remembered raptures with

refreshed delight; |

|

Whose days are very full live

far into the night. |

|

|

|

Frances Moore |

|

|

|

|

|

Midnight |

|

|

|

Flaps the ivy softly, |

|

Cold against the wall? |

|

Is the moon a-peeping |

|

Neath its cloudy pall? |

|

|

|

That's my love a-waiting |

|

Shadowed by the beams |

|

Harvest moon is making. |

|

Wind, what are her dreams? |

|

|

|

Lift the swaying curtain, |

|

Trip the mossy stone |

|

Round about the rose-bush |

|

Love we are alone! |

|

|

|

Midnight from the belfry |

|

Booms for them its bliss |

|

Age all lies a-sleeping. |

|

Youth can kiss. |

|

|

|

Kenneth B. Stump |

|

|

|

|

|

Modern

Magic |

|

|

|

In the year thirteen hundred

and seventy six |

|

The people of Hamelin were in

a rare fix; |

|

Though the issue was simple

and not politics - |

|

All over the town rats were up

to their tricks. |

|

They lodged in Hamelin's rooms

and halls, |

|

Below the floors, behind the

walls; |

|

Moreover - this truth really

shamed her - |

|

There were rats at large in

the Council Chamber. |

|

At length an angry population |

|

Flocked in a local

demonstration, |

|

Causing the Mayor and

Corporation |

|

To quake with a mighty

consternation; |

|

In absence of a quick solution |

|

The townsfolk promised

retribution: |

|

Let the problem be rats, or

the trouble be muck, |

|

The Council of Hamelin could

not 'pass the buck'. |

|

|

|

Six hundred long years later |

|

to us this story's strange; |

|

better does Bristol City |

|

its corporate chores arrange: |

|

|

|

Bristol has men and women who

toil day by day; |

|

They sweep the streets and

catch the rats, |

|

They heat the schools and feed

our brats, |

|

Unclog blocked drains; for

little pay |

|

They nobly clear our waste

away. |

|

Yet, as I write my ditty, |

|

To see fair Bristol dirtied

so, |

|

And see her townsfolk come and

go |

|

Mid refuse, is a pity. |

|

|

|

MUCK |

|

|

|

It overtops the dustbins, and

blocks the drains and sink |

|

It's pumped into the Avon so

that the river stinks; |

|

It's piled high in our

gardens, and litters all the Down; |

|

It's massed in heaps and

scattered on the pavements of the town; |

|

|

|

It clogs our feet and nostrils

though we avert our eyes; |

|

It lies in open spaces, and it

smells where'er it lies. |

|

|

|

I wish we had more people |

|

Like Hamelin's forthright

folk; |

|

I looked up Browning's poem |

|

And I read the words they

spoke; |

|

I imagine them in Broadmead,

on the Downs or at the Zoo - |

|

I overhear their comments, and

watch all that they do: |

|

|

|

Gazing wide wonderment at our

predicament |

|

Observing incredulous Bristol

ridiculous, |

|

They soon appraise it all, are

not amazed at all, |

|

Treat with derision our sham

indecision |

|

Avoiding solution, creating

confusion. |

|

To our body corporate in

forthright terms they state |

|

|

|

This firm conclusion: |

|

You need not seek Pied Pipers

of magic, good or ill, |

|

Your cleaners, sweepers,

wipers have the necessary skill; |

|

Our Mayor and Corporation,

knocked by our population, |

|

Gambled fifty-thousand

guilders |

|

To rid our rats and mice. |

|

You've got a better system?

Then pay up, don't resist 'em; |

|

Rise the fifty-five bob; pay

the rate for the job - |

|

Believe us; it's cheap at the

price.'. |

|

|

|

Barbara Smith |

|

|

|

If Things Go on as They Are |

|

|

|

If things go on |

|

as they are |

|

we shall soon |

|

have more cars |

|

than people |

|

which means that |

|

some of them |

|

will have to be |

|

driven by computers |

|

if the profit increment |

|

of the Stock Market |

|

is to be maintained. |

|

|

|

If things go on |

|

as they are |

|

what with all this |

|

plastic rubbish |

|

even babies will |

|

come wrapped in |

|

polythene and |

|

we shall all go to |

|

the Supermarket to |

|

take our frozen pick. |

|

|

|

If things go on |

|

as they are |

|

what with all |

|

these transplants and things |

|

my heart will be |

|

in Liverpool |

|

my kidneys will be |

|

in Bristol |

|

and my head |

|

will be in the clouds. |

|

|

|

If things go on |

|

as they are |

|

what with |

|

Electronic Telephones |

|

the cost of connecting |

|

you from A to B |

|

will be less than |

|

the cost of working |

|

out how much it is |

|

and the system, |

|

like the Oozlam bird |

|

will disappear up |

|

its own whatsit. |

|

|

|

Alan Prior |

|

|

|

|

|

War Maimed Girl at a Dance |

|

|

|

A hurt one |

|

A maimed one |

|

A doll of a girl |

|

A doll of a girl |

|

|

|

She watches |

|

They're dancing |

|

They're all of a whirl |

|

They' re all of a whirl |

|

|

|

Just a short raid |

|

Just a few dead |

|

A handful hurt |

|

Nothing more to it |

|

|

|

Tee tom tom |

|

Tee tom tom |

|

(I wish I

could dance) |

|

(I wish I

could dance) |

|

|

|

Tee tom tom |

|

Tee tom tom |

|

(I wish I

could dance) |

|

(I wish I

could dance) |

|

|

|

Rose Friedman |

|

|

|

|

|

Far From My Window |

|

|

|

Far from my window, far said

he, |

|

Ships skim the horizon, |

|

And boulders bend down to the

sea. |

|

Near to my body, near said he, |

|

Cogwheels spin my reason, |

|

And Metals move close to me. |

|

Fresh round my body, fresh

said he, |

|

Tulips and sapphires |

|

Cling to the tree. |

|

Stale to my mouth, stale said

he, |

|

Oils and grease |

|

Collect around me. |

|

|

|

Tony Whitfield |

|

|

|

|

|

Drama Now |

|

|

|

What a place for drama is the

countryside; |

|

Panic-bold a rabbit darts

across the lane, |

|

Death by mutilation only just

defied. |

|

|

|

Overhead the crows watch,

wickedly alive, |

|

Waiting for the pallid lambs

too weak to live |

|

Their dim eyes to steal, e'er

death itself arrive. |

|

|

|

Half-up the hill, the old

sheepdog plays his part, |

|

Watch him as he crouches,

coaxes, curls and twists, |

|

Dog and man together knit in

shepherd's art. |

|

|

|

In the hedge the whitethroat's

courtship song is sung, |

|

Poised on a branch he

pirouettes and patters, |

|

Till from his mate the

ans'ring notes are rung. |

|

|

|

Oh! What a place for drama is

the countryside, |

|

And lucky he, who sees the

pageant passing by, |

|

And seeing it finds all his

senses gratified. |

|

|

|

Winifred Froom |

|

|

|

|

|

The Dancer of Death |

|

|

|

And she danced, and she

danced, |

|

And she reeled, |

|

and she stealed, |

|

across blood sodden turf |

|

on that murderers field, |

|

and her feet as they

squelched |

|

upon gore and on flesh, |

|

the Generals they cheered, |

|

their blood red eyes peered, |

|

and their darkened mouths

leered |

|

at that stadium in Chile |

|

that stadium of death. |

|

|

|

And she span, |

|

and she ran |

|

her eyes full of glee, |

|

a quaint "grand jetes" |

|

on the graves |

|

of the slaves |

|

that once were so free, |

|

to the tune of the bloated |

|

that cackled and gloated |

|

and clapped bloodstained

claws |

|

at that stadium in Chile |

|

that stadium of death. |

|

|

|

As she swung |

|

her mind sung |

|

of the gold she would make |

|

for the ghouls and the

Generals |

|

that sealed Chile's fate, |

|

and they fed her with caviar |

|

with wine and with blood |

|

fresh from the graves that |

|

their soldiers had dug. |

|

Oh she danced and she pranced |

|

controlling her breath, |

|

her feet caked with blood |

|

Dame Margot Fonteyn |

|

he dancer of death |

|

|

|

Ian E Reed |

|

|

|

|

|

Elegy |

|

|

|

Now theirs is the

comprehension |

|

of the strain and strand of

the silky root, |

|

and the seed's division. |

|

They know |

|

the flaws where life broke

out, |

|

and the secret chemistry which

forced fruit from the rock, |

|

the disposition forming man, |

|

And how the first beat leapt. |

|

From earth's fat in slow toil

drawn erect, the |

|

cause and strength, the single

self; |

|

from dissolution at the first,

to unity, |

|

the dispensation was this; |

|

from the stillness to the

creating realisation |

|

in the individual reality. |

|

Now for them combine those

oppositions, |

|

twist, tug, and link, which

make the dry bones warm, |

|

the grapple and union on the

forge of thought. |

|

And so on will they flare in

the sun's last slide; |

|

and in their transmutation, |

|

the fullest communication. |

|

By their going forth they have

had assumption. |

|

|

|

Keith Lloyd Jones |

|

|

|

|

|

Person with the

grace of a tall ship |

|

|

|

Person with the grace of a

tall ship |

|

the frame of a humming bird |

|

the eyes of a peacock |

|

and the voice of the lilac on

a warm spring breeze |

|

Let the shrouds of what you

want to desire be lifted long enough for |

|

me to be in your eye a moment,

that I might, for that moment, stand as |

|

tall as singers and men of

property |

|

so that I might not be

condemned without |

|

soul or dignity to the shadows

of the gathering dusk as it whispers |

|

across the fields cloaking all

but the moon in black, |

|

and that you might see

reality, or me, for that moment. |

|

|

|

Jimmy Barnes |

|

|

|

|

|

North Scale's Winter |

|

|

|

Oh lonely beach so long and

flat |

|

Glistening the memory of a

recent tide, |

|

Reflecting the cold blue

winter's sky, |

|

Deserted forum of summer

pleasure, |

|

Buckets, spades, freckles and

sunburn, |

|

Forgotten behind frosty

windows. |

|

Only I stand on your silken

coat, |

|

Tasting the salt from icy

tears, |

|

While the wind moves you

always on, |

|

Goading your being to restless

wandering, |

|

I stare at your open face

listening for your secrets. |

|

But even now wrapped in the

same wind, |

|

I am only an alien in your

deep eternal doings. |

|

|

|

AM. Horne |

|

|

|

|

|

Father Crisp Sell |

|

|

|

Having sold his toys, |

|

Pleasing 1,000 yelling boys, |

|

Removed his scarlet cloak, |

|

A ribboned cracker joke, |

|

Pulling off a tacky beard, |

|

He winced and round he peered, |

|

Seeing no one in sight or

sound, |

|

Thank Christ for that!' he

shouted loud. |

|

|

|

A.N. Horne |

|

|

|

|

|

Last

Rites |

|

|

|

Sorry were we |

|

to put John down, |

|

not wholly because |

|

our turn would come. |

|

|

|

Back at the house |

|

full of wind and piss, |

|

someone had to say |

|

"John would have liked this." |

|

|

|

Bill Eburn |

|