|

ISSUE 31

cover size 205 x 295 (A4)

CONTENTS

This issue of VOICES was produced by Ruth Allinson, Mike Binyon, Ailsa Cox,

Ivor Frankell, John Cowling, Alf Ironmonger, John Koziol, Olive Rogers,

Bernadette Tweedale, Di Williams, Gatehouse Project, Scotland Rd. 84.

THROUGH THE MANGLE

Roger Mills

The elderly woman pointed at the clothes mangle and smiled at me. "Bet you

don't know what that is, sonny." I felt obliged to shake my head and tell her o,

just to give her the pleasure of being able to explain its purpose to me. In

fact, my parents had one in the back yard and we were still using it in the

sixties. It was obviously a source of pride for the woman, though, to find this

ancient relic from her youth dumped here with all its associations of family

washdays and shared work.

Now, if I were to tell you that the elderly woman, the mangle and me were

standing in the middle of the Royal Festival Hall in London I suppose I'll have

to explain what was going on.

Exploring Living Memory 1984 brought together exhibitions and stalls from London

reminiscence groups and with the help of the GLC was able to stage it in the

Hall's main exhibition area. Much of the exhibition consisted ' of photographs

and accompanying text, but there was also video, live theatre and music (plus a

mangle). I was there with the Federation bookstall, containing stock made up of

a selection of our books.

Over the weekend we sold a lot of Federation publications, particularly London

autobiographies. We sold them mainly to people who had moved out of the inner

city areas long ago and gone to the new towns. The organisers of the exhibition

made sure that hundreds of people had been invited in groups and that these

were, for the most part, those who had lived in the areas represented. These

people had grown up in some of the worst housing conditions possible, and in

great poverty. They were born in bug-infested back-to-.backs and played in the

streets alongside rats and mice. Yet there was a celebratory feel to the event.

I don't think this was because they'd come to think of them as the 'good old

days' and I don't think they were smiling at the thought that they were lucky to

be out of it either.

The event reminded me of my own discovery of local publishing. During a period

of unemployment, I wrote several prose pieces and while wondering what to do

with them I stumbled over Centreprise bookshop in Hackney, where I had lived all

my life. In the clearly defined local section I found A License to Live by Ron

Barnes. It was the first locally produced autobiography I had read. The working

class had been talked about before but it was the other classes doing the

talking.

The book was a revelation to me. History meant the working class too. We were

writing about ourselves and reading about ourselves as well - smashing the idea

that only the famous had a tale to tell, a 'result’.

The structure of autobiography is really just a clothes horse oh which the

author hangs experience, knowledge and philosophy. It wasn't until I started to

put my own life on paper that I realised the importance of emphasis, selection

and interpretation.

In practise, the Federation has never differentiated between autobiography/local

history poetry/prose and adult literacy. We have broken down the barriers that

elsewhere still exist between these written forms.

The people shopping at the bookstall at the festival were primarily interested

in the autobiographical and history publications. Some also went away with a

book of poetry as well, however, finding in a different arrangement of words an

expression of working class life as real and valid as the more clearly labelled

life histories. The Federation is helping to develop a positive attitude to

poetry and prose in a class that has been alienated from it in the past.

Likewise, more people are starting to see working class autobiography as the

vital act of creative writing that it is.

On the last day at the Royal Festival Hall as I was packing away the bookstall,

people were literally pulling the books out of the boxes again to buy them.

People are interested in themselves. Not in a selfish way - they want to share

their lives. Writing in all its forms gives us the opportunity to make sense of

it all.

Federation groups and publications give working people the space to speak for

themselves, the means of self-representation. What a clothes mangle does is

easily explainable; you put your soggy socks and shirts in it and it wrings out

the wet. What a clothes mangle might mean however is another matter, to be

interpreted individually according to the experience of the writer.

In all our hooks we are presenting admonishment and a challenge to the accepted

view of history and literature as a nuts and bolts twin tub machine, wheeled out

for inspection with a 'No Tampering’ sticker on the side.

Roger Mills is the author of A COMPREHENSIVE EDUCATION, published by

Centreprise

FIFTEEN MILES FROM GREENHAM

Kathleen Horseman

Menopausal disorder, never my friend, never shrug off the implications of

this woman's condition.

I had run the emotional gauntlet, been tender as a kitten, a real granny grimble,

fiery in my temper as a whirlwind, and as transient, all at the drop of a

hormone or two, metaphorically speaking of course.

My husband must have been hard pressed indeed to understand, and even in my

unstable emotional state I knew when he came home from his work, the momentary

pause would be there - what mood was I in? And I did try, really I did.

Nothing is forever. This cliché so well used is nevertheless true, and on the

Thursday I walked along the main road from my home to the Hut. I felt a need to

rejoin the human race, and the woman's group meeting that afternoon seemed a

good place to start.

I almost changed my mind about joining in with the small group of young women

sat round the table.

What did I have to offer? My friendship, interest - gently does it, I thought, I

mustn't be a knowall.

"Can I join you?"

I made some frivolous remark about being a granny rather than as they were, a

young mum.

"Yes, come and sit down, course you can."

A chair was dragged a matter of inches to be nearer to the table by a young

dark-haired girl who used her foot, hooking it around the chair leg nearest to

her to achieve this movement of the furniture.

In her arms, her young son sucked at orange juice from his plastic bottle.

All things are, I suppose, as in the eyes of the beholder, like the ugliness of

a building's windows, shuttered against natural light with wood and therefore

vandal proof; the table's top surface, multi-coloured splodges of paint, a

permanent imprint left behind by some one seeking a kind of release through

artistic achievement. The baby's bottle was thumped down, finished.

A packet of cigarettes, a child's interlocking plastic toy and an upturned paper

cup, all on the table.

We had taken our time, just minutes in fact. Now we were relaxed and could talk.

Children playing, identifying, who was who's, isn't he like you?

"Two boys, other people minded more than me when I had another boy. But I

didn't care, they're alright." "Aren't people daft?" "Course, I live with our

mum now, couldn't stand my husband any more, you've got to live with them to

know them."

The pretty pregnant young girl who sat across the table from me had seemed so

quiet, in a half asleep retreat of her own created protection. Gradually she

joined the conversation.

"I knew my husband years before we got married, but once we did marry he was

different."

"I'm back with our mum as well, but I want my own place."

This young woman impressed me so much with her brave yet realistic acceptance of

her situation, though I did give a thought to the parents of the girl with

grandchildren, nappies, all the disorder that must have returned to their lives.

Coffee was made, squash for the children. I wasn't sure that any of us really

wanted it but it was part of the ritual. One of the children spilt his drink and

it spread in map-like fashion to stain that part of the linoleum that still

adhered to the floor. I made a conscious effort to ignore its existence. I

didn't want to break our moment of shared yet somewhat fragile conversation,

especially as the young mother that I had been trying to draw into the

conversation began to tell me she hadn't been well since her baby was born.

"Women's problems" - she was shy, this girl, needing gentle coaxing, "go

to the doctor, don't be afraid, tell him."

I felt the harsh realities of life hurt some more than others and they are hurt

by their indifference to it.

I could go on telling of conversation where I mentioned THE PILL and they

laughed, "oh sometimes I forget to take it."

I asked, "What do you most want from life?"

"To be able to go out, just up and go, not to have to get the kids ready first.”

"No pushchair, freedom."

“I could walk with my hands in my pockets."

"But then I would have nothing to hang on to."

"No, I couldn't do without my kids really."

"No," I thought, "no, but one day!"

During all of this one little boy had been climbing on and off of my lap. I had

felt too tidy, somehow restricted by the neatness of my appearance, but this

child, uncomplicated in his trust, had recognised me even as a stranger and

called me Nanny.

I loved the baby warm smell of this child, and wanted with an uncontrollable

need to kiss the top of his head.

How I envied these mothers. '

But anger came too: "why do you come here?"

"Because it's free."

"What about the playgroup next door?"

"It costs too much. I got two children. I can get a loaf for that."

I was angry with the restrictions of poverty.

Angry with the ugly discomfort of a building considered good enough for these

women.

Angry with the ones with knowledge to impart and the ability to recognise the

potential and need of these women with years of life before them and who weren't

there.

Angry with myself, with an emptiness that stayed with me as I walked home.

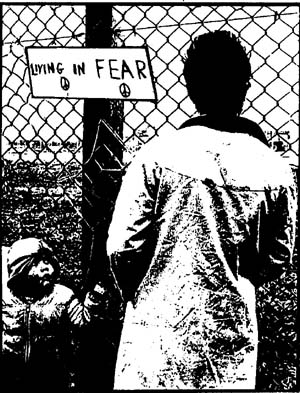

I thought of those other women at Greenhan Common, free from one kind of

restriction to fight against power of yet one other kind.

And I wondered at the difference.

I went into my orderly little council house where I looked for washing to

put into my automatic machine.

But I kept on the clothes that held just a hint of the smell of baby powder, and

Johnny.

KATHLEEN HORSEMAN

Kathleen Horseman is a member of Bristol Broadsides.

AND ANOTHER THING

The second collection of writing from Women and Words, a Birmingham women

writers' workshop. 56 pages. Price: £1.00, including p&p from Helen Pitt, 261,

Yardley Rd., South Yardley, Birmingham B25 8NA. P.O.'s and cheques payable to

Women and Words.

PENSION DAY

Alf Money

There was an air of nostalgia

in the long queue

at the local post-office, yesterday,

we were all there

dressed fop the occasion,

in our garb and finery,

the stoopers, the limpers,

those with some kind of cross to bear,

the sprightly, the unsightly,

the hold on to my arm dear tightly,

clutching our treasured passports

to modern world existence,

the long buff pension book,

there we all were, kids again,

bouncing down nostalgia lane,

chittering, chattering,

nittering, nattering,

of course the owld times crept in,

amongst us all,

"Remember in the Twenties, Jim,

"Aye a do an all, Alice,

t,owld penny rush,

at local picture palace,

the essence of it all

flowed amidst the post office queue,

and we wallowed in the gooey sentiments

for a while

Jack, Joe, Bill, and canny owld Sue,

laugh and tear and whimsical smile,

cough and splutter, guffaw, mutter,

all of us owld uns, and the odd young uns

caught up in that magical trap

the far, far off past,

getting our allotted pension,

and giving away free,

those owld memories, worthy a mention,

for them that wanted to grab them,

same nostalgic charade every pension day,

week after week,

a kind of senior citizen ritual,

so to speak,

"Aye, it's nice ter wander back,

wot der you think owld Jack?"

"Well a don't know,

past is past, an future's here ter stay,

owld rigmaroles dead an gone,

so a expects we've just got to carry on

an make the most a wots left fer us,

so lets call it a day,

see yer all next week God willin',"

"Penny for yer thoughts owld timer?"

"A penny nee good, my thoughts

a worth an owld, owld shillin',

an that were money in them days

when a was just a young un."

BUS STOP

John Walsh

Standing at the bus stop

feeling the wind hating it

watching the traffic

cars

driven by smug faces

think

glad I got that loan now

taxi's

with eyes that know

flirt their ebony welcome

call me

I'm nice and warm inside

but I will cost you

all your beer money for the week

lorries and vans

roar past

neither seeing

nor caring if they did

then the bus arrives

a bright green comfort

promising warmth and escape

until

"sorry pal, we're full up"

and it's back to the cold

the waiting

and the wind.

TO CATCH THE POST

Liz Verran

Helen rushes to the front door mat - two letters. She takes them into the

kitchen and pours herself a cup of coffee - she'll need her drug before opening

them. The first is from the Dolly Girl Bureau, telling her that she hasn't got

the post as secretary to an accountant in the City. "You were their number two

choice because you didn't sell yourself hard enough," they helpfully tell her.

Helen could have cried - she remembers the last time she had.

She was so heart-and-soul determined to get this one, she had looked at

timetables to see what train she would get morning and evening, thought about

how she could take an active interest in the charity she would be serving and

had read its reports in the reference library. She had prepared for every

conceivable question, she thought, but some one else had come along who had

worked for a similar charity before, and experience counts for all in this game.

The pain of that rejection was so great that she decided next time to hold back

some of herself.

She hopes the second letter will tell her she hasn't got an interview. "I can't

take any more pain just yet." It is just as she feared and hoped - an interview

with another agency, leading to the insult of shorthand and typing tests,

followed by another interview at a firm, followed by another interview if she is

shortlisted, only to fail at the final hurdle.

Helen puts, on a fairly formal suit and tights (ugh). Will the interviewer be

man or woman (men are impressed by sexy scent, women repelled)? She arrives at

the agency fifteen minutes early - too soon to annoy them with her presence, too

late to get a cup of coffee. She wanders up and down the road, getting her hair

windswept and her tights muddy.

The young woman gives Helen a form to complete (number 41, she mutters to

herself) with far too much space for work experience and far too little for

education. "I'm really hoping to do something administrative," she ventures.

"Oh, you can't waste your secretarial skills," warbles the interviewer.

Helen hates servicing men but if she were to say so secretarial/ administrative

jobs would be barred to her from this agency if not all, so she keeps mum, and

the first barrier to communication is built.

"You don't mind taking a typing test, do you?"

"No," says Helen through grit teeth - she has a typing qualification which

proves her standard is far above what any boss could require, but the process is

a mindless machine which, once set in motion, goes on to the bitter end. She is

so angry and tense, her typing is full of mistakes.

"I'll have to take those off your speed, dear. It's not as good as you thought,

is it?"

Thoroughly humiliated, Helen hangs her head and does not defend herself.

The next few days are spent in boredom and frustration - she daren't leave the

house for long in case she misses THE telephone call. Eventually it comes, and

she is invited to be interviewed by a group of holding companies with mines in

South Africa and Namibia.

The Personnel Department of Afro metal Holdings is concerned that Helen is over

thirty but has only three years' work experience (she had been "wasting" her

time in the thankless task of bringing up children). They think her shorthand

speed is not high enough - hardly surprising since she had escaped the cage of

secretarial work for over a year, and only the fact that her employers didn't

like her union militancy has driven her to the need to find work again. How will

she explain the year when her work was limited to routine office tasks because

she was being victimised? Come clean about her background and frighten off their

capitalist souls, or try and cover it and be totally unconvincing?

She meets her potential boss - middle-aged, humorous and friendly. The interview

is informal and Helen relaxes. She apologises for the folly of not finishing her

degree - "I was silly enough to get married and short-sighted in thinking I

would not need a career." (I can't tell him I left on the verge of a nervous

breakdown through depression. I'm sure 1 sound spineless and giddy.) He is

impressed by her personality and her confidence in dealing with important

people. He is amused at her feminism - just an eccentricity. She has re-assured

him that she is not REALLY anti-men or anything horrid like that.

As Helen thought, she did make a good impression and is told a week later that

she and two others are being invited back for a further interview with a

publishing company to do part secretarial, part administrative work. It sounds

more interesting, but she's put her heart into getting the job at Afrometals.

Still, she can't miss an opportunity so she accepts, knowing it will lead

nowhere as her mind will be preoccupied.

She has her period on the day of the third interview - she feels suicidal every

month since being unemployed: she never noticed periods when she was at work.

She arrives to discover that she will face a board of three men: her prospective

boss, his manager and the Head of Personnel. They sit in a row behind a table on

slightly higher chairs than hers so they can look down on her. As each asks a

question she replies to that one, aware that the others are scrutinising her

intently. She starts to sweat. Helen is at her best in informal situations but

this formality destroys her confidence (what little remains, that is after

twenty rejections). She is very conscious of her looks: mature enough? frumpish?

intelligent? or arrogant? How can she, a revolutionary, convince them she would

love to join their team exploiting the wealth of South Africa? They keep

returning to the question of whether she is over-qualified for the post. Far too

intelligent to be satisfied as a secretary she may be, but Helen knows she has

left it too late for a career and she would gladly settle for the relief of

having a permanent job for the first time in three years.

Helen leaves, dejected; she knows she didn't make the most of herself. "All that

emotional investment, and they still don't believe I really wanted the job.

Would I have got it if I'd lied about my education? But how would I have

explained what I did between the ages of eighteen and twenty-one? Or if I'd

prepared an answer to the question about where I thought my career would

develop? What career! If I'd had ambition, they would never have considered me

as a secretary."

She could, of course, comfort herself with lies. "I'm blacklisted. It's because

I'm such a threat to capitalism that I can't find work" but no, she believes

other myths: "I'm a complete failure. Nobody wants me because I'm just not good

enough." How many like her believe that unemployment is their personal problem

rather than the fault of a system that throws women and men on the scrap heap

for the sake of profit; that doesn't recognise child-rearing as useful labour?

She has a job now - working full time against the system that spat her out like

a bitter pip. She lives under a plastic sheet outside Greenham Common airbase,

building a community with women and children that is not based on privilege or

profit. She campaigns against male violence - nuclear weapons, rape,

exploitation - and dreams that her daughters may one day work using their

abilities not their feminine wiles.

Liz Verran lives in Gillingham, Kent. She works as a secretary to a trade

union official.

MEAT SANDWICH

Maurice Gosney

I am jobless, I am worthless, I am homeless,

And you are not.

I am desperate, I am desolate, I am separate,

And you are not.

I have torments, I have troubles, I have trepidations

And you have not.

I have uncertainty, I have unhappiness, I have uneasiness,

I have understood,

And you have not.

I am angry, I am unwanted, I am dangerous,

And you don't care.

I am without hope, I am without a future,

And you don't care.

I would like to change the system, and you would not.

I would like to change you, and you would not.

I am the surplus pool of labour.

I am the meat in the sandwich of capital and technology.

Hurrah for the brave new world,

Electronic gadgetry, video illusions,

Micro trickery and computerised trading,

Automation and Robotation,

Concentration of Investment,

For the elimination of repetitive, boring

Manual and semi-skilled occupations,

And the maximal, optimal production output,

With the least number of hourly paid operatives.

Welcome to the High Tech Age, full of rich enjoyment.

Begone you waged labour man, begone you full employment.

See the dancing robots, automatons at play,

Sweeping all before them, I am swept away. .

I am redundant, removed and retired,

I am dismissed, relieved and fired,

I am disheartened, discarded and disgraced.

I am the meat in the sandwich of Investment and Science.

Hooray for the Micro Way, Hooray for the Bright New Day.

Tell me of the pleasure, and tell me of leisure,

For I am the relic of boom time measure.

I am not old, I am not young,

I am the heart, and the brain and the lung,

I am the army of surplus labour,

Shedding its blood on the technocrat's sabre.

I am myself or any other, uncle, father or my mother,

I am me, I am them, I am those, I am us,

I am you or your brother,

I am the work ethic, I am the workforce, I am the worker.

WE ARE THE MEAT IN, THE SANDWICH.

TEXT 55

Terry Cuthbert

Dear Sir,

I wish to appply for the job as secutory to your firm, I no& i have not no

exberiance like an yet i feek i am jut the man, person for the job, uno- I can

use all tge bin words neaded, e.g. 8Situationwise, outputs i dont know whar they

meen of corse but then i dont surppose you do neither cock, Whom ever you enbloy,

i am sore it qill bee someone of my bavkground, after all cock, you need us

grityy workin class, its us wholl pur you in strikes and expose any sandles

between you and your female staf, we all nos what gos on do we in thuse big

ofesis do we gaffer, go on bang yout fuvking fist afaindst your oficse drinks

cabernot and ahad mit it, you ned someone lije me as your secadery, can you do

without my talent you wanker? i an sure we8ll have a @appy and long relanoshilxp.

i am 3x: 56 and livbig in the simon hostol and atdenig the alco ospatele so tou

see don8t yer mate, i am the right basterd for the porshition eh cock?

Yors Faiffuly

Terry Cuthbert will be known to readers of past issues as Blackie

Fortuna.

A sample from bloody L.I.A.R.S., a sketchbook of poems by Michael Rosen,

cartoons from Alan Gilbey and press cuttings from everywhere, including MILITANT

and MUSEUMS AND GALLERIES IN GREAT BRITAIN. £1.50 + 50p postage from 11, Meeson

St., London E5 OEA. Cheques to Michael Rosen.

CLASS

Rebecca O'Rourke

CLASS 1

Conjure up the images:

Glossy, stylish, upmarket.

You've either got it or you haven't:

classy little number.

I'm not talking about that.

I'm not talking about

"a structural relation to the means of production"'

either.

Which isn't to say that I don't think

some own the means

and some are the means.

Because that's true.

I'm trying to talk about history.

My own years of it.

This country's one thousand, nine hundred and

eighty odd years of it.

I'm trying to talk about a relation

about cultures

about ways of life.

I understand when you say

we're all people

I don't believe in class.

I understand, too, when you say

middle class has become a term of abuse.

If we can't all be socialists

it's patronising

it's insulting,

I understand that,

I've got my state education too.

But,

Middle class is more than a term

it is abuse.

It's a relation,

a culture,

a way of life.

And I'm implicated in it -too.

It seduced but didn't marry me

Doesn't house me, inherit me.

If I want it,

I want it out of lack.

I want 'middle class'

because, 'middle class'

is talking nice

and I can do that too,

Because it's warmth,

and comfort,

cars and carpets.

Middle class isn't

outside toilets

cold water taps

lino

sliced white bread

second hand clothes

second hand furniture.

Middle class isn't

chapped hands

snotty noses

shoes that rub.

Middle class isn't

gangs on the street

wild time and the coppers round the corner.

It isn't shared beds

going hungry

empty spaces.

Middle class isn't

being told not to presume

being told to work hard

in your secondhand school uniform

and non-regulation shoes

with your cheap pen

that leaks all over the page

and stains your fingers.

And you must be grateful girl

and think of god.

Aspiration is what it was all about.

If you will talk like, look like,

think like us

We'll let you in

When I was eleven

I lost all my friends. !

They didn't make the grade.

Six of us from a final year of eighty-six

passed a test we didn't know we were taking.

And it took three years

to make some' more.

It took getting quiet

and talking different.

It took scandal

When my father made it

by the front page of our local newspapers

by being sent to jail.

And when our headmistress,

most holy Sister Francis,

explained she couldn't ask me to leave,

But if I was to say

I thought it better that I did

they could arrange it

I was the centre of attraction.

And I dug

my worn down heels in

and thought I'd try it their way.

But you don't forget.

The 'O' levels and 'A' levels

and grants to go to university

don't mean a lot

in Chorlton and Hulme and Stockport.

They mean something

they mean getting out

they mean a crack in the sky.

We were all schooled in Macmillan's forcing house.

Get a degree, they'd say

Don't live like us, don't die like us.

Great aunts, uncles, the first to go

from little houses in Leigh and Wigan

and diseases of the lung.

Yes, they all smoked,

but some of them worked the mines.

And, more recently,

Dan and Tom and Steven and Pat,

leaving widows and children, some of us

with our bits of paper

qualifications, mortgages

A different way of life.

But families are strong

and you don't forget.

Pat worked in the fifties

erecting pylons across the country

And when that was done

and electricity lit the nation

He found a dark little corner in the docks

pleased that in the sixties they'd dropped the tally

and you didn't have to fight for work.

I remember him as a child

coning home to Russell street

and eating huge meals of soup and bread.

I remember a tin horse

he gave me, and walking back from Alex Park

how he bought a whole quarter of chewing nuts

just for me,

something else in his pocket for Kevin and Susan.

I didn't visit him in hospital

dying of stomach cancer

This huge huge strong man

who'd frightened and fascinated me.

I was at the funeral,

out of place.

Talking to Steven, dead a year later.

i

And Dan, before him, in Belfast.

Both dead of heart attacks.

Before they retired, all of them.

A life of work, for the likes of me.

And I can't easily

with this heritage, with this knowledge,

accept comfort, security, progress.

I can't define my interests and my needs

separately from those

of the class that made me.

Because all that I've had

I've seen paid for,

life by life.

I've seen the loss at which I got my gain.

Nothing slips down easily:

not my past,

in which ashamed of where I lived

and what my father did,

I've denied it

pretended I didn't have a brother or a sister

My past in which I lost myself

CLASS 2

Class is about conflict

and yet,

it grieves me that a woman I like

is so removed from me.

Feminism doesn't seem to make it easier

at times like this.

I know, you know

we share, as women, much that is common.

The way we're treated

looked at

thought of

what we can and can't do,

We find unity in that

but whole areas of experience and expectation

clash between us

when we try and talk of class.

And we're not just talking it:

we're living and have lived it.

You've never told me

and I've never asked you,

what it was like,

A strange land lies between us.

If we are ever to traverse it,

or even map it out

for future reference

we must first make the journey back ourselves.

I would hardly know the way.

I remember signposts, crossroads:

early marriage

illegitimate children

eleven plus failure

These mark my way:

I need to rediscover all the roads I didn't take.

I don't know what guided me;

mistakes my mother had made perhaps.

But I need, for her,

to make a more courageous stand.

To say, yes,

the violence, the fear

the terribleness of it all marked me

kept me on the narrow path

to independence and success. '

But more than that.

I have to give them their due

for every time they told me off

when I said I couldn't be or do something

I said I wanted |

because I was a girl or we were poor.

Mum and Margery with their friendship

and their strength

taught me women don't need men

in order to live and be happy.

And ray dad taught me about socialism

in practical ways

by being generous and good

and showing me which books to read.

I cannot trace out

the way they formed me.

But I find myself now,

uncertain of the future,

uncertain of the past

with some small strength.

I believe in a basic goodness

about the way

we think to live.

I don't deny your sisterhood

or your comradehood.

I recognise that we are here, together,

separate in our histories,

separate in our reasons

And I do not deny that we look to the same future

We could be dead in five or fifty years

It's important to me

that we don't waste the time.

There is nothing we can do to change the past,

maybe even the present,

but we must be together in the ways the future asks.|

I want to know

where it was and wasn't the same.

I want to know the difference.

It has to be the first

THE OLD COUNTRY

Ken Worpole

A now familiar envelope

Arrives each year from Ireland

Or Eire, as the postage stamp

Reminds us in runic lettering

On a small green square,

Like a lonely headstone or deserted obelisk.

The address is wrong, meant for next door,

It is not our letter but each year

We hesitate and open it and,

Unsurprised, read the familiar card:

'To Hughie and Bridie, always in our thoughts,

From Eamonn and Kathleen in the Old Country'.

They've been dead five years at least,

Hughie and Bridie, she followed him in weeks;

Their flat's been lived in twice since then,

Re-decorated twice, no one would know

They ever lived here, the old couple,

Except for the Christmas Card which

Brings them back to life again each year

Like a resurrection, a second life,

Which they in fact believed in,

Though they left no forwarding address.

BRISTOL DOCKS

Tony Charles

Textured glass: rust, amber

and cinnabar smouldering, melded

slab to slab on slick lead:

lights on water; you cannot see the oil spilled

Silhouettes of cranes

support the low cloud, cross-members and stays,

dense and delicate, drinkers of light,

nodders of stiff heads; not threatening

nor making statements.

And the warehouses do nothing,

leaning together like burnt-out

trolley-buses. They do not moralise

this urgent groping at cold bodies

under coats and sweaters in unlit

archways.

Couple; part; and re-arrange

your clothing. Smoke.

A youth with string and a woollen hat

quarters his rounds,

gathering newspapers for his night's

rest.

DON'T SAY

Keith Armstrong

Don't say it's nothing to do with you-

there are bullets in your speech.

Don't say it's nothing to do with you-

there are guerrillas on the beach.

Don't say it's nothing to do with you-

there are black birds lying on your bed.

Don't say it's nothing to do with you-

there are soldiers firing in your head.

Don't say it's nothing to do with you-

there are children starving in your stomach

Don't say it's nothing to do with you-

there are lies in the words you vomit.

CANCER ROOM

Steven McNee

Cancer sticks

Their life's habit

Wasting away my lungs

With unquestioned taint

Relaxing, making my ruin

Hovering grey white

This bluey dense poison

Before my sight.

Stumped there dead

Smelling stale

Feeling sick, turning red

I'm looking slightly pale.

Now with belching cough

Wheezing until I'm tired

Then feeling rough

With fresh air desired

Breeding me a cancer

Here in this room

Making a failure

In slow dying doom.

CLOUDS

Steven McNee

How you seek the blue sky

gliding through each others' subdued and endless path

Finding no more, no less but a hiding place

alone; above a hill's wintry white cloth

With the wind your master of high and low

Your distance goes.

Over and over you roll;

Slowly, dreamily as I gaze up, here below.

Away and afloat you pass by on a swollen lake

Fresh wind swept mountain sides.

As you navigate through jagged surface rock

of glistening snow covered tops.

REMEDIAL CLASS

Maria Sookias

Get your books ready now 4c.

And Maria it's time for Mrs. McFee.

A jury of eyes are scorning at me,

Convicting an idiot...ILLITERACY.

Slowly I rise avoiding smug stares,

And head for the door with uneasy flair.

Bag on one shoulder, I'm told not to chew.

I spit out the gum and utter "Stuff you."

I head for the room with thicko's and dims,

Hearing arch angels practising hymns.

There sit the rejects, all solemn and still

Each in their own world, intent on the kill.

War of the words, battling books.

The general enters, I'm sure the floor shook!

The onslaught begins and so does the sickness.

Line by line, "I'm not feeling well Miss."

The rigorous pages are mapped alphabetically.

Counting my classmates, attacking strategically.

Plotting planned paragraphs that I'll have to stutter.

I turn to a neighbour, "What's this say?" I mutter.

Remembering long words and guessing the short.

I'm bullshitting on and haven't got caught.

Odd words I don't know the general obliges.

On into darkness, my heartbeat rises.

The beetroot sits down in relief that it's over.

"An improvement, well done." The thick cow, I loathe her.

The end of the lesson and certainly hopes.

I'm told I can read, I can't but I'll cope.

Trapped in deceit, so I'll lie till I'm rumbled.

Crying I'll giggle, though I feel I might crumble.

I'VE HEARD IT

Anne Fazackeley

The end of your sentence - you're over the moon,

This time will be different - we'll be married soon.

You know who your friends are, you'll happily say,

The one who stood by you while you was away.

"Just you and the kids, love, stuff all my mates."

That's what you said as you walked out the gates.

But both of us know that within a week

You'll start to ignore me each time I speak.

You must think I'm stupid, believing your lies.

Well, stupid or not, a time will arise

When you will need me and I won't be there.

Where will your friends be - do you think they'll care?

It happens to everyone - you'll get what you earn.

The next time you're nicked - this worm's going to turn

LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT

G.P. Andrews

INTRODUCTION

name GRAHAM PATRICK ANDREWS

born 19 FEB. 1961, MIDDLETON ON SEA, SUSSEX

education LIMITED

spirit HIGH

compassion MUCH

doctor martin boots TWO PAIRS

I leave my P45

and my UB40 cards

to the government

as a celebration

of my wasted youth

I leave my empty

savings box

to the chairman

of ICI

In which

he can keep

all his spare

£50 notes

MUMMY I WANT

THAT ONE!

Mike Lynch

Sunday afternoon was showtime at the Elm Tree Children's Home. All the

children who were offered for fostering or adoption were scrubbed clean, dressed

in snow white rompers and laid on long brown tables. Like roses at a flower

show, we all had our names strapped to us. Babies who threw up on the floor or

wet their rompers were whisked away to some unknown destination and promptly

replaced by a dry substitute.

At 2.00 p.m., the doors were flung open. Hand in hand, couples came rushing down

the aisles, searching for the best babies. Babies screamed when prospective

parents tickled their turns to the rhythm of "citchy citchy coo". The whole

event was conducted like a church hall jumble sale. Being the only non-white

child on display, I received most of the attention. Couples crowded round just

to have a look; to most, I was a bit of a freak, like a five-legged dog or a

three-eyed budgie.

A middle-aged couple showed a lot of interest in me. They had a spotty-faced,

nose-picking three year old with them. When she saw me she clapped her hands and

gasped, "Oh. Just the little thing we were looking for." She went on to tell

matron how she had had her son late in life and she could have no more children,

so she wanted something nice for Billy to play with. If I could have spoken at

the tender age of eight months, I would have suggested a box of soldiers or a

teddy bear; but since I couldn't, I just had to gurgle contentedly and play with

my toes.

It looked like I was going to join the Clayman household, but after a few more

visits to Elm Tree Mr. and Mrs. Clayman had second thoughts. They tried to get

Billy to have a big-blue-eyed blonde-haired little girl, but Billy firmly stood

his ground.

"No mummy, I want that one" he said, pointing at me. I felt like a cheeky but

lovable sad-eyed mongrel dog.

So, after a chat to the matron and welfare department, the official

paraphernalia was signed and I was their foster child and they were my legal

guardians.

WHA' HAPPEN BLACK GIRL?

Wha happen black girl

You know here about family planning

how you just ah' breed so

And you Mr. so call black brother

Me know you believe in spreading the seed

but what life can you offer to the girl

that you just breed

Poverty and misery

Huh' but nourished with fools love

you think that you can support even the

Lord above

And when the children grow up

Ma what you gonna tell them

Dem papa was a sailor

He was more like a tailor

You know see him sew up your life good

and proper.

The work by Mike Lynch and Angela Mars in this section is

taken from AS GOOD AS WE MAKE IT, a collection of work from the

Centreprise young writers group.

extract from

ME AND MINE

About the age of nine, Christopher noticed there was another new baby, just

arrived from the baby shop, so his mum said.

This really annoyed Christopher, because he was only just getting to like his

younger brother Ray, who had suddenly started school.

The funny thing about Ray was he used to like his bottle - a hard habit to

break.

Instead of being on milk, Ray was on the hard stuff - tea. He used to hide his

bottle up his jumper when anyone came in.

He also hid it under the cushions on the sofa. Christopher knew this because he

never missed much.

One day Dillis, the local nosey parker, came in to see Christopher's mum about

something. Ray hid his bottle then hid behind the armchair. He only came out for

meals or the adverts on T.V., which were his favourite things on T.V. at the

time.

Halfway through a cup of tea and a gossip, Dillis and Christopher's mum were

interrupted by a loud scream. It was Christopher dancing up and down, waving

Ray’s bottle in the air. Poor Ray went red and didn't know where to look.

Ray came from behind the chair and kicked Christopher on the shin then ran into

the back kitchen.

The new baby, Shirley, was no trouble, except for the pile of dirty nappies she

made every day. Having no washing machine, the kitchen sink got blocked up a

lot, which annoyed Christopher's mum.

Christopher tried for a number of jobs, he finally got a job as a chain lad. He

was to get fourteen pound a week.

For this he had to stand in two foot of mud and knock six foot wooden stakes in

with a hammer he could hardly lift.

The continual swearing of his boss, plus the other heavy duties and dirty jobs

he had to do soon made him decide he didn't like this job, so he gave in his

notice. One of the funny things that happened to Christopher while he was there

was one of his wellies got stuck in the thick mud.

His face was a sea of mud. The world was black - well, dark brown anyway.

The boss stood there red-faced and shouting, then the boss slipped on his

backside in the mud.

The next job Christopher got was a car park cleaner. The wage was £8 a week. He

started that Monday morning: they didn't give you a brush or shovel. You had to

use your bare hands to pick up everything, from fag ends to dog dirt. All they

gave you was a plastic bag, which came out of your wages.

They also had nowhere to go to the toilet or to wash your hands. You'd eat your

dinner walking about, in your twenty minute dinner break. That evening,

Christopher was getting fed up. Some of the disgusting things found on a car

park floor defied description.

Worser was to follow, as Christopher was getting his coat on his boss told him

he was nightshift tomorrow.

So they only expected him to work seven to eight hour shifts for £8. Christopher

stormed into the manager's office and told him where to stick his job.

What Christopher really wanted was a shop job. Though low-paid, he liked it. It

was a great feeling - hard, honest work.

He tried everywhere, but his appearance put people off. He couldn't afford new

clothes.

Christopher only got £3.50 from the youth employment office. He gave £3 to his

mum; that left ten bob to last him two weeks.

Eventually, after he'd been called over to the social security three times

because he'd been out of work two months, he was soon broke.

The old man over there looked through all the papers and made you go for every

job, whether it was low paid, or even if you weren't qualified for it.

He didn't think about the wasted time or where the bus fares came from.

Eventually a miracle happened. Christopher was granted an exceptional needs

grant to get a suit or to try, with the princely sum of £14.

Even then, most suits were £25 to £30, for the cheapest, that is.

EYEBALL EXPLODER

Chris Darlington

My dad worked in a slaughter house

Stale blood on his boots smelled for miles

I thought what a cruel job he had

He was chief eyeball exploder.

For hours I used to watch over him

I sat staring at his eyes,

In case they exploded,

While he slept.

HEY!

Alan Hayton

You in the black leather jacket,

with a single earring!

What keeps you warm inside

on a cold street corner?

Love, friendship, humour or

what else?

As the rain sweeps past your view of massive concrete

courtyards and buildings, and of nothing else;

and an emptiness in the air, in the whole formation

of the world outside yourself

inviting you only to despair, grow empty too:

the corruption of a system blocking all alternatives

having done its best to narrow you

to drugs, mind-blowing decibels at discos,

space invaders, star wars; cynically

offering you nothingness as life itself.

You, though!

Hang on to your hopes, your loves, your passions anyway,

and the warmth in you. Believe

in a time that's better, in a warmth beyond yourself,

that's shared. This ice age is a fraud,

the fabrication of a dying class. And there's

a life and future that's worth fighting for;

just around the corner.

Alan Hayton's book of poetry, FAR CRY FROM 1945, is

published by Pertinent Publications, Scotland.

WEEPING WOMAN

I'll be no weeping woman here

Hiding behind a man to mask my fear

Taking those kisses tinged with frost

And watching eyes shielding love long lost

I'll be no weeping woman here

Holding my man with a rope of tears

Clinging to memories best forgotten

I'd rather be dead and buried and rotten.

OUTSIDE IN

They called her an alkie , me mam

Playground taunts and gossiping cows,

"Never walks straight, smelt her breath

I pity her kids, God help her husband,

He's a good strong father a lovely man."

Outside, pity they never knew him inside.

They called her an alkie' me Mam

"Don't talk to her, don't play with her kids

And how does she cope, such a lovely man

He's a walking saint, a saint, you know

And she's a sherry stinking drunken bitch."

Outside but no one knew her inside.

They called her an alkie' me Mam

Said she didn't clean us, couldn't be bothered to feed us

Said she was a whore a tupence ha'penny scrubber

Said she only kept us for state allowance,

Said she didn't care just staggered round the street

But they only saw the outside, never saw the inside

They called her an alkie', me Mam

They called him a saint, me Dad,

But they never saw her crawling kicked to the floor

They never saw her vomit in naked waiting fear,

And they never saw him punch her like she was a man

You see them outside, they never saw the inside.

Terry Brennan

LETTERS

Write About It

As an ex-secretary of VOICES, Scotland Road (VOICES 30) depress me, since they

cannot find a space for black, female or gay exclusive groups within the

Federation of Worker Writers. I left VOICES to form Northern Gay Writers two

years ago. In the five years I have been at Commonword, I have co-produced

twenty-nine worker writer publications, only one of which has been exclusively

gay; and my own Commonword 'gay' novel is in fact for the most part a working

class, black, immigrant and homeless gay journal. My five years have been spent

editing VOICES, WRITE ON and other projects such as a battered women's handbook

and the autobiographies of unemployed and retired working people. I have spent

many years encouraging black and prison writing.

But without the support of a gay writing group, which in turn has the support of

Common-word, I would have left the FWWCP when I left VOICES, the

reason being that I am not prepared to serve on a working class committee

as a minority of one, the token gay, the

stereotype gay treasure. Nor do many women fit the mould of

(1) silently taking the minutes of a loud, male dominated meeting, nor (2) being

elected the first and hoarse woman chairperson. Blacks

and Asians do not cherish being patted on the back as if they were a token, an

exception or futuristic trend nor it being inferred that as a minority versus

majority decision, they have a chip on their shoulder. But this

inevitably happens in any organisation; it can only be countered by

black, women and gay exclusive groups interacting with other groups.

Writers' workshops which are predominantly white, male and

heterosexual may only at the most hopeful be 5% black, 5% gay and 15% women. No

doubt the interests of the 75% will predominate.

Cynical, rude and offensive I am, but I can assure you that there is a lot more

to people's politics and liberational writing than throwing every writer through

the same mould. I'm not going to apologise to the FWWCP any more for the fact

that I am different, yet still socialist and working class.

Similarly I would hope that the FWWCP would find it in their hearts to encourage

more exclusive groups, i.e. prison writing, unemployed, gypsies, homeless and

single travellers, agricultural workers, council tenants, psychiatric patients,

Asians.

Otherwise I feel our organisation can only help writers develop until they wish

to specialise. Perhaps on specialisation writers should leave.

Also I consider the type of person who feels he has a right to sit at any group

or family table in his town or country is not particularly sensitive to

the needs and feelings of others.

The oppression of race and sexuality is, and always has been, fairly universal;

in fact it predates and shapes class politics. Sexual and racial divisions of

labour and property started economic class.

I remember being asked "How can you be a writer and be working class?" Now I can

also add to the list: "How can minorities and women form their own groups and

still be in the FWWCP?" Doubtless we know of the demagogy and purges of Stalin,

McCarthy, Hitler and public spending. This battle is being fought. This time

don't let humanity be the loser

JOHN GOWLING (Commonword)

Dear Editor,

When the American vocalist Joe Hill

was being beaten up in a prison cell by the reactionary bastards (there were

more of them then) he sent out the words: "Don't sympathise, ORGANISE." He then

belonged to a very courageous trade union called the I.W.W.

The advice I give to all organisations connected with Voices. Within reason. If

you get cash from new subscribers, acknowledge or you could lose such important

people.

As for writing, stop having post-mortems with every issue. Just keep going. The

results so far are good, damned good, when you consider the poor educational

background of most. To hell with the Arts Council cash. We'll get by without it.

Others, in the past did it before the Arts Council was formed.

Remember, we have a lot to learn from middle class writers some of whom have a

general sympathy with our clan. Where is there a better description of fear of

poverty than in Somerset Maugham's Of Human Bondage? Or of problems of a long

strike than in Germinal by Emile Zola? Keep reading and writing.

Yours aye,

PETER KEARNEY (Glasgow)

We're sorry we can't acknowledge every subscriber, or keep contact with the

huge number of people who send material. We're a small, struggling group and

hope you'll be patient with us.

- VOICES editorial group

SUITS

Mike Rowe

AN AUDIENCE WITH THE GOVERNOR

The Governor must reckon that I'm not a full shilling. He had me up in his

office yesterday just before finishing time.

"I don't know how much this means to you," he said, "but it means a lot to me -

the Company is on the verge of securing a large order. You can tell the lads on

the shop floor their jobs are safe."

THE GOVERNOR'S GUESTS

It was bloody freezing in work today. At ten o'clock The Governor and two other

Suits were walking around the factory; having a good butcher's at all the

different operations, weighing everything up with eyes like ferrets. The

Governor nodded briefly as they passed my bench. All three of them had thick

overcoats on.

FIRM BUT FAIR

C.W. Warrington-Dolby, Managing Director, The Governor's boss; his name carried

a rare majestic elegance, even when rolling off a tongue as rough as mine.

Before I ever set eyes upon the bloke I had built up a vivid impression of him,

solely on the basis of his splendid name.

C.W.T. Warrington-Dolby: ex-Guards Officer, Old School Tie Brigade; tall,

portly, of jolly disposition - firm, but fair. Old Man Gross, the Company's

founder, could undoubtedly rest easy in his grave, knowing he had left the

business in such capable hands.

C.W.T. Warrington-Dolby turned out to be nothing remotely like the above. He

inherited the Company by sheer default, being Old Man Gross's only remaining

relative. He was small and thin, with a black wafer-thin moustache and greased

back hair. On the occasions that sight was caught of him at the factory, it

would be a very fleeting sight indeed. He would climb out of his Rover and

scuttle across the courtyard towards the Company offices as fast as his little

legs would carry him; his head down, eyes glued to the ground, studiously

avoiding eye-contact with any of his employees whose employment necessitated

their presence in the courtyard at the same time as himself. He left the

day-to-day running of the Company to The Governor, preferring to oversee

operations from the sanctuary of his golf club bar.

NICKNAMES

Most of the Company's employees refer to C.W.T. Warrington-Dolby as "Dolly";

some of the younger shop floor workers call him "The Rat" on account of his

facial features; The Governor talks of him as "Himself", I myself go along with

the Rat contingent; although, I feel obliged to admit, this inclination is

mainly due to the obvious deficiencies of the other two contenders: I've seen

dollies, C.W.T. Warrington-Dolby looks nothing like one - and the mere thought

of the term Himself being employed in such a manner causes my scrotum to tighten

most uncomfortably.

A POINT

The Governor must reckon that I'm not a full shilling. He has a point, I

suppose, after all, it's him who's wearing the thick overcoat.

I'm bringing my woollen gloves tomorrow.

OLD MAN GROSS

The longest serving Company employee is Louis the Storekeeper, he's got

forty-odd years in. Louis openly admits that he's very lucky to be still working

for the Company. Throughout the fifties and sixties Louis was in the habit of

sneaking out to the transport cafe down the road at 10.05 precisely each

work-a-day morning, for a mug of tea and a bacon sandwich.

One particular bright summer's morning in the late sixties, unbeknown to Louis

at the time, Old Man Gross didn't happen to be feeling too good. At 10.10

approximately Old Man Gross called for his faithful Chauffeur, Spencer: "Take me

home, Spencer, I feel unwell."

As Louis was coming out of the transport cafe at 10.20 precisely, who should he

see riding past in

his Daimler but Old Man Gross - and, as these things go Old Man Gross had

spotted Louis too: he stared directly at him, "An icy stare chilled my bones to

the marrow."

That night, when Louis returned home, he told his spouse to prepare for the

worst; "Tomorrow I shall most likely be out of a job."

It was with a heavily furrowed brow that Louis clocked in at 7.30 the next

morning. Upon starting work he found it near impossible to store-keep in his

normal efficient manner; he found himself staring fixedly through the Store's

window at the Company car park, anticipating the arrival of Old Man Gross's

Daimler.

At 8.45 Louis saw the Works Manager's car draw onto the courtyard, a good three

quarters of an hour earlier than usual. The Works Manager, Arthur Wardle - it

was well before The Governor held the position - called for the Foreman, as soon

as he got into his office.

On his return to the shop floor, some ten minutes later, the Foreman summoned

the entire workforce around him; within a couple of minutes he was confronted by

a semi-circle of forty or so curious workers. The Foreman got straight to the

point, endeavouring to keep the loss of production down to a minimum; he told

the assembled group that Old Man Gross had passed away in the back of his

Daimler on his way home the previous day.

A RESPITE

Now and again, to get out of the cold, I go into the Foreman's office for a

quiet smoke. The Foreman, Nobby, obligingly lets me use his office to collect my

thoughts. In return I pretend to be his friend - his only friend. Nobby is

despised, at best, and hated, at worst, by both management and workers alike -

but somehow he manages to survive. As the shop floor workers whisper among

themselves when the job has Nobby under severe pressure, "You can do it Nobby!"

ROUGH AND READY

The Governor is a rough and ready, up and at 'em, take me as you find me sort of

bloke - but he always' wears a smart suit. He is tall, tubby, broad-shouldered,

clean shaven, with fair curly hair and bulging eyeballs. It is undoubtedly this

last characteristic that inspired a renegade contingent, Johnny-come-latelies

for the most part, to ignore his official nickname and refer to him instead as

Golf-ball Eyes.

The Governor is of that rare breed of people who assiduously work their way up

from the shop floor to a position in middle management. He started his career

with the Company straight from school at the age of fifteen. The older workers

on the shop floor, who remember him as both a raw Apprentice and, later on, a

young Journeyman, recall that he was "a right lazy little bastard."

The Governor's Father also used to work for the Company, he was a Progress

Clerk. It was his Father who secured the Governor his Apprenticeship to the

trade.

THE FORTUNE HUNTERS

I get paid weekly, very weekly. I cannot manage my home and affairs on the

weekly recompense I receive, though there are some who continually remind me how

lucky I am to have a job. All my workmates are in the same boat as myself; that

is why the majority of them are always willing to work overtime at the drop of

The Governor's hat. I think it would be fair to say that all of the shop floor

workers are only in it for the money; with one exception, Nobby.

Nobby conducts himself as though he would be perfectly willing, if required, to

lay down his life in service to the Company; that is why he is despised, at

best, and hated, at worst, by both management and workers alike.

Were Nobby to be served notice of the Company's intention to dispense with his

services, I am quite sure he would no longer be willing to die in the execution

of his duties and beyond - and I am equally sure he would amend his behaviour

accordingly, his work effort would slacken off appreciably; he would betray

little - and, depending upon the skill of the pumper pumping him, large -

confidences, formerly shared by himself and The Governor. This situation has

been known to occur from time to time - Foremen are generally easy to replace -

such a dramatic abandonment of loyalty is known affectionately in the trade as

"When rogues fall out."

WHAT DO YOU WANT?

"I wonder what the Suits who were walking around with Golf-ball Eyes wanted?"

"Perhaps they're here to place a big order?"

"Or to shut the place down."

"The Governor had me up in his office yesterday, just before we were going home.

He reckons the Company are about to secure a large order; he said, "Tell the

lads their jobs are safe."

"Oh yeah! I've heard that one before! They told us that at the last place I

worked - a couple of days before they made us all redundant."

"Aye, I suppose you never know, the state the trade is in nowadays."

"I'll tell you one thing, I kept my eyes on my tools while they were hanging

about - they looked the type of blokes who'd prise the shite out of a dog's

arse, given half the chance."

"It's funny you should say that. I noticed one of them weighing up my hammer."

"Bent bastards]"

"It's cold today, isn't it? I'm bringing my woollen gloves tomorrow."

WE'LL NEVER BE SLACK AGAIN

Nobby had a quiet word in my ear as I was putting my tools away at finishing

time. He told me that the two Suits who were walking around with The Governor

were at the factory to place a big order: "We'll never be slack again," he

chortled gleefully.

You can do it Nobby!

Mike Rowe makes packing cases in Manchester,

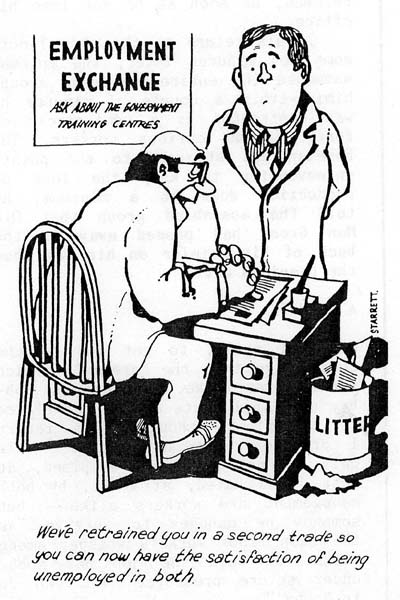

If you've enjoyed Starrett's cartoons in VOICES, you can novi buy a book of

them, from Ferret, Press, 10a, Queen Margaret Drive, Glasgow 12. Price: £2.75.

His targets include bigots, capitalists and warmongers. His heroes are the

proletariat.

EMPIRE OF SMOKE

Mike Jenkins

Inside the house, the sideboard glistened

like cut coal, the dust was embarrassed

and hid its face below the carpet.

My mother fussed around making slippered

and comfy comments, blessing the house

with a cloth to anticipate his homecoming.

His spade-wide hands with coal-dust

mapping out wrinkles like a chart of aging,

turning over the egg and bacon

as if he were revolving a globe.

Canaries still whistled like old boots

in his talk and pit ponies stampeded

like Derby Day: images snatched from the dark.

In the park I saw the parrots gossip,

their plumage the colour of her bright lipstick,

preening themselves like her feathered fancies

in front of every mirror. At night I heard

the jackdaws' rock-fall: his voice croaking

from their throats, dry as a swarm of dust.

These sounds were almost suffocating.

And then, hypnotised by my sister's success

framed, in pride of place, above the fire,

they talked of London as if it were Lord

of the Manor, deeming to greet them from behind her face.

They were escaping the church clock's spying gaze,

the weather-groans raining from mouths.

I walked out into the infirm landscape.

ADDICTED

Bel Walsh

Skull empty. Brainless

too little, yet too many thoughts within

no crimson heart beating

no murky brown liver churning and lurking

no magnolia, intestines digesting

no inside, completely void

A fragile china doll ready to crack open its

already broken frame

Just skin and skull, only bones and flesh

stomach maybe present - when hawking and

retching

but never felt

Body rocking - mind heaving and heavy with

nothingness

heavy footsteps trudging up and down my

ribcage

So kick it - I thought - kick the habit!

Completely. Totally. Have strength

No strength. So hard. Too bloody hard!

Withdrawal - must have withdrawal

Calm. Calmer now.

Must keep taking the pills

till sweet sanity resumes its beautiful

presence

Addiction too horrendous to give words too:

words alone seem too silly

Oh how beautiful it will be

When I'm not addicted anymore!

and my whole nervous system will heal

like a grazed knee.

REVIEWS

A HACKNEY MEMORY

CHEST George Cook, Centreprise

A friend of mine who spent her childhood hiding from the Nazi's in occupied

Poland has, in an attempt to block out those hideous years, completely forgotten

Polish - her mother-tongue until she was thirteen, when she finally left Poland.

I spent most of the year 1953 suffering from pulmonary tuberculosis at High

Carley, a sanatorium near Ulverston on the edge of the Lake District. an

experience which I found traumatic and on my return home I did my best to forget

it, which had the effect of dulling my memory as regards the happier times which

preceded it.

With greater courage than either of us, George Cooke delves deep into his

memories of a time spent suffering from pulmonary tuberculosis in 1940, and

these in turn lead him back to recollections of his childhood growing up in a

Hackney working class family in the thirties. The author is only .five or six

years older than myself, a relatively prosperous working class child (my father

was an artisan) growing up in Lancashire in the thirties and contracting

pulmonary tuberculosis in my early twenties, so this book is of great interest

to me as I compare my returning memories with his.

Leaving aside this personal interest, however, A Hackney Memory Chest is an

excellent book, conjuring up both the indignity and the joys of working class

life as experienced by a man. As Rebecca O'Rourke points out in the

Introduction:

"Men rarely write about their personal lives or publicly accept those intimate,

tender sides to their nature." This book is welcome on that score alone.

I particularly enjoyed the author's recollections which match my own of the 'Bisto

Kids', the 'bobbies' or "coppers ', the horse and carts used for milk

deliveries, street games, the seasonal ones particularly, like 'whip and top',

the Saturday cinema shows for children in Hackney known as the 'Tupenny Rush'.

Later, like me, he enjoyed the heart throbs of the day - Norma Shearer, Joan

Crawford, Loretta Young, Claudette Colbert, Ronald Colman, Clark Gable, Spencer

Tracy and the singers Jeanette McDonald and Nelson Eddy. We are also told about

the 'peasouper’ fogs, the radio series 'The Man in Black' with Valentine Dyall

telling spine-chilling tales, moonlight flits - the list could go on and on.

The latter part of the book deals with George Cook's experiences in the

sanatorium. In the same way as mine, his tuberculosis was discovered by a

compulsory check-up. I understand only too well what he means when he writes:

"It seems odd, but I must have grown with the disease in the .respect that I

never realised myself that I was ill". There is an amazing account of his

undergoing major surgery in the form of a thoroco-plastic, which at that time

had to be completed in three separate stages under local anaesthetic. Thirteen

years later, I was to find myself with a scar of over eighteen inches long which

traversed my shoulder blade on the left side like a railway line with a minor

branch line branching off at the junction lower down, but my operation required

only one stage and I never had to wear a surgical belt as George Cook did to

support his weakened side.

There are lively descriptions of the patients and staff at the sanatorium, some

funny, some sad, and overall this is a book where pleasure and pain are

intermingled. The hardships endured by working people are not sentimentalised,

but neither are the worthwhile parts of their lives denigrated. A Hackney Memory

Chest contains many interesting photographs and is a valuable social document of

the recent past.

RUTH ALLINSON

MARSHALL'S BIG SCORE

-

John Gowling, Commonword, £1.20

Marshall's Big Score is the worker writer movement's first gay novel. An

achievement that might embarrass some, or feel like a contradiction in terms to

others. "Can you be gay and really working class?" seems to be one of the

questions at issue in the recent debate about Northern Gay Writers, and I think

for some people in the Federation the answer is yes, but only if you keep quiet

about it.

Keeping quiet has never, thankfully, been one of John Cowling's strong points. I

have always enjoyed his writing in Voices, Write On and Nothing Bad Said. Part

of the attraction has been the vivid, racy description of a time and place I

grew up in. I think we all find it very powerful to read about where we've lived

our lives. It validates these often unremarkable places that have rarely figured

in print. Growing up in Stockport, it never occurred to me that anyone could ever

write about the place. It, like our lives there, wasn't what literature was all

about.

The other reason that I respect and enjoy John's writing is that I admire the

courage and honesty with which he writes about his own sexuality. Homosexuality,

in John's writing, is never the be all and end all, and Marshall's Big Score

isn't an argument for homosexuality, a coming-out novel or a defence of Gay

Rights. Being gay is simply there, as it simply is there for gay people. Except

of course that its being there can create a whole set of problems - yours and

ours.

Quite a lot of Marshall's Big Score, the account of the progress of a love

affair from the summer of 1976 to June 1979, deals with those problems. But,

again, as he writes of the problems around housing, families or jobs, it is as

much an account of working class experience as it is of gay experience.

"We had this old TV with a coin meter, which Jimmy had also tore off. The telly

had meant that we had money for food, for a night of good shows on the box would

keep us out of the pub. On top of the box we had a green lamp which made the

black and white screen less dull and more toned; and as its light reflected our

actions in the inky green-black window, it made it appear as if we too were on

T.V. It brought the programmes into our room so to speak." .

Through his love affair, Martin grows to a sense of awareness about himself, his

needs and rights in the world which are part of, but much wider, than his

sexuality. On the way to this, we travel with Martin through a variety of places

and situations - Liverpool dock-side, gay squats in London, bedsits and squalid

flats in Manchester, all described in that graphic, bitter lyricism that is

characteristic of John's writing. As you would expect of a first novel, the form

isn't perfect. Sometimes it seems we are moving jerkily from one fragment of

life to another. This is partly, I think, because some of the novel has already

appeared as short stories in various places, and I came to know it first as

episodes. But partly I think it is the nature of the situation and life-styles

he describes that they are episodic, fragmentary and often at a tangent to

themselves. In this sense, the form is appropriate to his subject. There is also

the problem we all know, of how to carry in our heads that sense of characters

and action developing and being sustained over a piece of writing of novel

length when we have to scratch around for the odd hour here and there for our

writing.

The novel has a lot to say about a lot of things, but inevitably it will be

mainly read and judged by what it has to say about being gay. For me, one of its

main values in that respect was that being gay isn't sensationalised or

presented as the preserved of over-indulged, aristocratic boys and girls. You

can be - are - gay in unromantic Reddish, and that matters; not just for people

growing up gay in that, or any other, working class area in this country, but

also for people growing up heterosexual too.

REBECCA O'ROURKE (Centreprise)

After the

Election, Keith Armstrong Robbie Moffat

"After the Election" is a tape of poetry by Keith Armstrong, founder of the

Tyneside poets, and the Tyneside writers. The reverse side features Glaswegian

Robbie Moffat. Listening to poetry on tape, as an alternative to the all

pervading "music" is an enjoyable and reflective experience.

I appreciated hearing the poet speaking his own verse, as one does in the

worker-writer groups. However, being robbed of vision, I did wish for a little

variety of voice once in a while. I should love to hear "The Jingling Geordie"

set to music-it almost took off anyway. The "Pub Poem", told at speed, might

improve with a change of voice. "Pierced Silences", a less characteristic,

rather sad and lost love poem, full of lovely beach images, could have been

shared with a female voice perhaps. Certainly a female voice somewhere on the

tape wouldn't have been amiss.

I enjoyed all the poems - although I had my favourites -

both for the broadness of interest, and for the skill in

poem-making. They range from "The Florist" - which manages to move from a

description of a flower seller to a philosophic whole view of "This Island" (of

Britain) - to a lamenting verse of solidarity "sung" to the people of El

Salvador.

"Hieronymous Bosch" starts with a description of his paintings, which almost

comes alive, and ends envisaging a modern, peopled Bosch scene-"They're building

the greatest nightmare ever around you, but your hands have grown too stiff to

paint.". As with the other poems, I liked this one at first hearing, but the

more I put my earphones on, the more the images in the poem became complete.

"To My Father And My Mother" is a moving dedication to his parents for bringing

him into being, bringing him up, and for continued support. The poem makes it

clear that in his background lies Keith's source of real wealth, and his depth

of thinking.

Many a poem had lines which I wanted to memorise for their "universality", even

as the rest of the poem receded. "Sounds In the Night" ends with the lines "no

one is ever self-taught, there are millions of people in every single thought."

The "Jingling Geordie" is a brilliant description of a poor, working class

caricature of a man, "made a fool of the stumbling system, emptying my veins

into a rich man's palace."

"After the Election, the title piece, has an air of not surprising depression,

with images of cages, people on the dole with nothing to do, hardly venturing

out of their box homes; "around a cricket field three times a day, a sad man

walks his dog." The starting poem "Map of the World" in contrast, exudes the

excitement of visiting unknown countries, of crossing boundaries and finding

things out, and then returning to well-known "home truths".

Robbie Moffat's poems on the other side of the tape, are full of lighthearted

visual accounts of his travels, particularly in India, but also in his native

Scotland.