|

ISSUE 30

cover size 205 x 295 (A4)

CONTENTS

EDITORIAL

Literary merit? Don't let it scare you. When I look at the more tasteful

magazines - those which represent the flower of "our" culture - I feel proud to

be a part of VOICES. Not only because we care about what we have to say, but for

the sake of technical proficiency. Look at "Decline of the Hull Fishing

Industry..." in VOICES 26 or "Last Liner" (27).

Yet many of the best pieces in VOICES draw their power from a waning source.

Poems, in particular, are often farewells to a world their author knows is

dying. They describe an industry in decline, or they may dwell on an aging

workmate or relative.

Fewer and fewer of us belong to that world of traditional manual industry. That

doesn't mean we don't need to be told what it is (or was) like. But if working

class writers are to have a future outside of absorption into the "mainstream",

we must have more to show of ourselves. It may not be so easy writing about

slopping out bedpans on a hospital ward, or working on a checkout or taking

fares. Those kind of jobs don't have the ready made imagery of the steelworks or

coalmining or ships at sea - no fire or molten metal. Nor do the people doing

them have the confidence in their own experience that generations of trade

unionism have given men in heavy industry. Yet they are parts of our lives, as

are many areas besides what we're doing if we are at work at all.

I know there's lots of good writing that never turns up in the VOICES office.

I've heard people in my own group shy away, saying their work isn't "right" for

VOICES; or carefully select a piece of work they think will make the right

impression on the editors, even though it isn't really the best they can do.

There is an idea that something exists called "Voices material", which must be

about something obviously political, preferably to do with work, probably set

thirty years ago, and which proves the author's working class credentials before

the first sentence has finished. What this boils down to, is that people

submitting to VOICES are consciously or unconsciously imitating the rules that

we condemn in commercial publishing; they're fitting their writing to a

preconceived market.

There is no one working class, any more than one writer's experience will be

identical to another's. There are working class people brought up in council

flats and gerry built private estates, as well as those well-known terraces.

There are teenagers and pensioners, women and men, black, white, Asian, Chinese,

gay and heterosexual worker writers. That's obvious isn't it - but that's not

always the picture in VOICES. We should take that variety as our strength. Our

strength consists of more than putting slogans into rhyme or spelling out our

politics in blinding neon signs. To me, working class writing is about making

visible the under-rated, challenging the assumptions in our own heads, as well

as the wicked "media".

So far as my own group, Common-word is concerned, I've always wanted us to

represent city life today and to find new ways of describing it, taking a pace

and a mood in the language from the experience itself. In VOICES, too, I'd like

to see work that is adventurous in style, yet loud and clear in its message.

More sanctified writers live in country cottages or academic suburbs; they don't

have our advantages. That's why they spend their time counting the pimples on a

toad's back for those other small magazines.

We should all know that this is the time, more than any other, when we need to

identify ourselves. The traditional rhetoric of the left has crumbled under

Thatcher. Images of our past have been tamed into nostalgia by the makers of

advertisements. We need new images and a new language as much as we need to find

new ways of fighting back.

This article is a personal contribution and does not necessarily express the

views of the whole editorial group.

DEAR GREAT GRANDFATHER

I have your marriage lines;

I hold them now

In my dying hand;

A yellowed leaf,

Folded, refolded, many times:

Henry Thomson, pitman,

To Martha McCloy, millworker,

In the parish of Dalry

In the county of Ayr,

This 26th of September, 1874,

James Armstrong, assistant registrar:

A fine official copperplate,

Neat as his pinned cravat,

To diminish your slow signature,

Howked from a difficult seam

With clenched fist, protuberant tongue,

Today as I scrape for the words

That might defeat the years.

Pen dried by the dross

Of worked-out sentiment,

I can think only of you and Martha

Wandering up the Linn Glen;

Sunday afternoons above the river,

Above the stour of pit and mill;

Clean and free, clean and free.

IT DON'T GO TO YOUR BOOTS

Jean Archer

Food meant a lot to my grandmother, especially potatoes. After church, the

most important area in her life was the kitchen, and even in the most drastic

years of rationing she could turn out a meal that a first class restaurant would

have been proud of; but not even for Lent would she give up potatoes and she had

been known to give up every kind of luxury for Lent. We always said she had a

cast iron stomach and in middle life, when she must have weighed about eighteen

stone, the family lovingly called her "potato face".

Maybe it was the passion for that particular vegetable that was responsible for

her whim to visit the pie and mash shop or maybe it was the slightly sour smell

of the parsley flavoured "likker" as it was called, that attracted her. It

reminded her of the sour white cabbage soup that in Polish was called Capoosta,

which she made so beautifully. Whatever the reason, the next time she and mum

and I went down the market on a Saturday, she bulldozed mum into visiting the

shop for a "taster".

"Voss dis pie and mash I hear so much?" she asked. "Must be good, yes?"

She'd based this assumption on the length of the queues she always saw outside

the shop. The queue usually consisted of the shabbiest, most undernourished

looking women and children to be seen even in those days of austerity, but since

she'd long ago dismissed the English Cockneys as a godless, feckless lot, who

spent all their money on beer, lower in the social scale than the even scruffier

Irish, who were at least Catholic, they didn't in the least put her off. The

fact that many of them carried basins and saucepans in which to carry away the

delicacy only served as further recommendation for it.

My mother tried to warn her. It wasn't the kind of food she was used to, it

wasn't "our" sort of place, it would upset all our stomachs seriously, and so

on. Mum had some experience of these places. She was second generation Polish;

she knew, but Nanny was determined. So to my great delight, for it was my first

visit too, we joined the line. Like a larger version of the Queen Mother, in her

best pink coat and hat and pearls and smelling of Yardley's Lavender, Nan stood

sniffing with pleasurable anticipation, oblivious to the nudges and stares of

the basin and saucepan brigade, mum, head lowered and biting her nails, hid

behind her and I passed the time by exchanging kicks in the shin with the little

boy next to me.

"You vurry too much tcorka*," Nan told mum. "Alveys you vurry too much. I big,

grown up vooman. You just eat, eat."

My grandmother, with her unshakable faith in God, was nearly always serene and

unflappable, although on the rare occasion when she did lose her temper, all the

family ran for cover from those strong peasant arms. She held the firm belief

that everyone would be a lot healthier and all the doctors out of business if

people didn't worry so much. As she often said, shaking her head sadly: "It

don't go to your boots, you know."

Inside the shop and right up to the counter, her round face continued to glow

with anticipation, even when the half burnt pies landed heavily on her plate -

all three of them. It was when the mash was being dished up that she began to

frown. When she started tut-tutting, I knew immediately it was because of the

lumps in it. Nanny's mashed potatoes were always smooth and creamy. Mum, with

her superior prior knowledge, asked for hot eels, but I would settle for nothing

less than what Nan was having, even though I was only allowed one pie.

We shuffled through the sawdust on the floor to one of the wooden booths and put

our plates down on the marble table top. They must have had big women in mind

when they built those booths. I could never imagine my grandmother squeezing

into the seat of a present day Wimpy Bar.

"Be careful. Whatever are you doing '- you'll tip it all over the table," my

mother, on pins and needles shrieked, as Nanny tilted the plate over for a

better scrutiny of the pies submerged under the likker.

Slowly and silently, like a surgeon Nanny dissected the first pie, sniffed it

and peered inside.

"Green? Voss dis? Green?" she repeated. "Parsley inside also?"

She took a forkful of this olive-green meat and raised it to her mouth and Mum,

abandoning her hot eels altogether, covered her face with her hands. From under

them came a faint murmur:

"You're supposed to put vinegar on 'em..."

Too late Nanny had already swallowed a large mouthful.

"Vinegar? So sour already I should put vinegar...?" and her Slav cheekbones

slanted up at an even sharper angle in company with her turned up Slav nose. A

glutton for punishment, she cut into the pastry and concentrating hard, moved

her jaws up and down. She suddenly threw her knife and fork down so that they

clattered across the marble table top ending up in the sawdust. As she pulled

the mangled morsel from her mouth, she sloshed it down so hard into the likker

and mash that it sent spots of green and white up her pink coat.

"Pastry? Diss is pastry?" she demanded of Mum who looked like she was trying to

slide down out of sight under the table. "Can't chew! Like rubber dis!"

All this while her voice had been rising in pitch and volume until every face in

the shop was turned our way and the guvnor came out from behind the counter to

investigate the fuss. Sensing what was coming, I was shovelling food into my

mouth so fast I almost choked. I wasn't going to be cheated out of the treat I'd

craved so long. But then I was always a child who would eat anything.

"You got a complaint, missis?" the tough looking guvnor said, making it sound

more like a threat than a question.

At times like this Nanny fought a running battle with the English language. "I?

Me? I? A nicer vooman you couldn't vish to meet. Vid neighbours - no trouble'"

"Be quiet mother, people are looking at you," hissed Mum, tugging at Nan's

sleeve. They weren't just looking, they were muttering too, mostly about "bloody

foreigners" and "'oo does she think SHE is ?" which didn't worry me in the least

because I already knew we were bloody foreigners. I just carried on eating as

fast as I could, even ignoring the out-thrust tongue of a sticky-faced child who

was leaning over from the booth behind with her chin on Nanny's shoulder.

"So?" my grandmother shrugged. "I don't mind they look - they don't know no

better - and you - " she pointed her finger at the pie shop man. "You should be

in prison - take good money for bad meat."

'"Ere, I've 'ad enough of you!" "You swindler.'" Nan's face was scar-The guvnor

pointed to the door. "Go on, out," he said. "Bleedin’ troublemaker!"

"Chizzler," Nan shouted. "My boots I could sole and heel vid diss pastry."

"Out. Go on," and as the man moved menacingly toward the table, a cracked voice

from behind me said, "Must be a Jew!"

"You don't clear orf now, I'll 'ave the law on yer."

Nan shot up from her seat, sending the sticky-faced child flying over backward.

"Goot. I go vid you to police station - fetch a pie - sole policeman's boots

too. In prison they should put you."

By now my mother had succeeded in pulling Nan out of the booth and she in turn

yanked at my elbow, preventing me from consuming the last few sloppy spoonfuls.

"Come Helenka," she insisted, her colour already dying down. "Vee go buy Syrup

of Figs," she smiled at me. "Then vee go home and nanny make nice latkis*, eh?”

*latkis - a kind of potato pancake

*tcorka - daughter

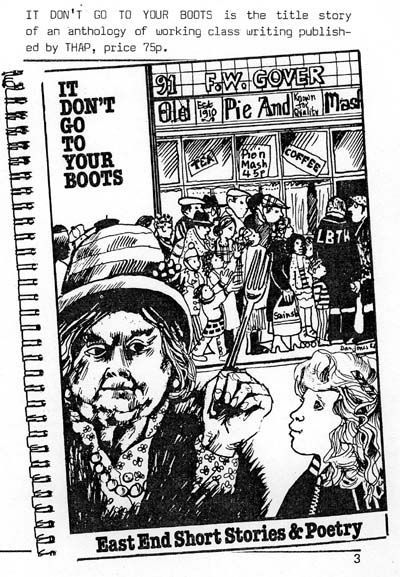

IT DON'T GO TO YOUR BOOTS is the title story of an anthology of working class

writing published by THAP, price 75p.

THE ASIAN

Julia Isaac

All alone in an alleyway

walked an Asian man last night

Although he knew it wasn't safe

he thought he'd be alright.

The alleyway seemed quiet

cause he couldn't hear a sound

But hiding in their hide-outs

There were skinheads all around.

The Asian man walked quickly

And his footsteps echoed loud

Near the ending of the alleyway

There stood a skinhead crowd.

He could hear abusive language

And the sweat poured from his face

Then some one shouted

PAKI, you're one step out of place.

Don't hurt me please, he begged him,

I have nothing, can't you see,

What fun, what joy, what laughter,

Will you get by hurting me?

They took all that he had on him.

They also took his clothes.

He just lay there unconscious

And the blood poured from his nose.

He's dead, one of them shouted,

And it's no longer fun.

They threw the weapons down on him

And all started to run.

All alone in an alley

lay an Asian man that night.

Half dying and half naked,

That really wasn't right.

Far off in the distance

The skinheads run away

Who will be their victim

In another alleyway?

BELFAST

Bronwen Williams

In sunshine

Painting my house

On Sunday, with the bells ringing.

Careful preparation.

A cheerful colour.

Still the old paint lifts

Even after two coats.

FINGER PAINTING

Chris Darlington

I did a finger painting of a finger

It was the finger of suspicion

That I pointed at you last night

With it I beat out a tune of hate

I was spelling jealousy in the dust

But the finger I painted belongs to you

Now it plays a silent symphony alone

With that finger you sent me away

The bacon slicer took it today.

VAUXHALL BRIDGE

Sue May

There's a Turner sky

with a sun like a fried egg

in the fog.

On the bridge a bandy legged man

is walking in the wind

like an elastic nutcracker.

All the Thames is rushing off to Tilbury

in bunches of ripples

and glitters of furrows.

A lonely barge battles the tide

weighed down with ballast.

Under the floorboards

Under the floorboards

a girl watches the window

o

CO

ico

lico

stop

doors open

Pimlico

Sue May is a member of Hackney Writers.

MICHAEL SMITH - MI CYAAN

BELIEVE IT.

I saw and heard Michael Smith read at the event that closed the London Black

Book Fair of 1982. He had the effect on his audience that I have seen in other

places when performers put across the use of Jamaican or other Caribbean

language with an audience that is used to having their speech ruled out of

order; people gasped, laughed, applauded with the release of something

forbidden. The forbidden stuff was the meanings he expressed as well as the

words he used. Life in the ghetto:

Doris is a modder of four

get a wuk as a domestic

boss man move een

an bap si kaisco she pregnant again

bap si kaisco she pregnant again

an mi cyaan believe it.

The he-man response to these conditions:

Mi use to live ina one

Little yard

Which part everybody

Think dem better off than de other

An di only thing mi could a do

Fi mek dem know dat mi nah

Skin up

When de area ready fi erupt

Is fe mek dem know dat mi is a man

Dat will bun up harp and tear off

House top because I got some wicked toughts

Mi a tell yuh trainer.....

Michael Smith was killed in Kingston on 17th August 1983, an attack apparently

carried out by heavies associated with the ruling Jamaican PNP. He was

twenty-eight. The human and cultural loss of his death has not been recognised

enough in the British press. I cannot speak, as a white reader, for his value

for Black people in this country. I know he helped me, as a straight, truthful,

non-partisan, radical, witty voice of the Black situation; and he still helps

me, as a teacher, to argue that Black English as it is spoken is a real language

that can carry meanings that must be told.

If you want to hear and read his work, he has an album M. cyaan believe it on

Island Records, ILPS 9717, with the words printed on the sleeve. The record

tells you a bit about one essential

element of his work; that it was with and for and close to an audience that

doesn't care so much if something is labelled 'poetry' as if it is a sharp truth

they need to hear. Listen to him.

Some a guh call it awareness

An wi a guh celibrate it

With firmness while others

A guh call it Revolution

But I prefer liberation

Fi de oppress an dis-possess

Who have been restless a full time

Dem get some rest

It a come

Fire a guh bun

Blood a guh run

It goen feh tek yuh

Not only fi I, but fi yuh too.

Sue Shrapnel

Sue Shrapnel is a member of the Write First Time Collective.

THE LODGE LANE WOOD WAR

John Walsh

To us, bonfire night wasn't just bonfire night. It was the night which showed

which gang was the best. The night the winners of the wood war would emblazon

their victory in scarlet plumes, that would rise higher than the rooftops.

The outbreak of war would start with the usual stockpile of bangers appearing in

the shop windows, and our mums and dads promising to buy us some fireworks, even

though they weren't as good as the ones in their day. It was also the signal for

the collecting of wood and the volunteering to begin. Volunteering was when we

offered to go on messages, for anyone we thought likely enough to reward us with

a tip. The tips were saved for one thing. Bangers. The pride and joy of any

would-be army on the eve of bonfire night. They would become the badges of

bravery as everyone tried to prove how hard they were, by holding them longer

than anyone else. They also became the symbol of pain, for those foolish enough

not to be content with being second best. Bangers, squibs and rip raps were

always the best fun on the night. Bangers for impressing the girls, rip raps for

scaring them. And squibs, well, they were used for the more meaner type of fun.

Squibs were like miniature rockets with wings. Ideal for firing off window sills

and doorsteps or up the entries at courting couples. They also proved great

favourites for firing at crowds from a distance or at doors of neighbours you

didn't like. I remember I was mean enough to use one once. I aimed it at old

Bob's door across the road from where I lived. He chased me, a few days earlier,

for playing football outside his window. I lit the fuse and off it went.

Straight to old Bob's door. And then he opened it and stepped out. Old as he

was, I've never seen anyone move so fast. He went back inside with the door

shut, just in time to hear the squib thud against the outside. I didn't hang

about to commend him on how fast he was.

But what the wood war really meant was the gathering of wood for the bonfires.

It also included pinching as much as you could from the other gangs. In our

area, at the bottom of Lodge Lane, there were three gangs. The Mozart Street

gang, the Coltart Road gang, and the one I was in, the Handel Street gang. The

other two gangs were on either side of us, with us stuck right in the middle. We

were a bit like the Israelites, surrounded. To make matters worse, Mozart Street

had Dougie's, the little street shop that was our main supplier of bangers, and

Coltart Street had the debby.

The debby was the bit of waste ground that used to be two large houses. The ones

with toilets inside as well as outside, and a bathroom to boot. A lot of people

wondered why the council hadn't bothered to build new houses on the debby. Some

reckoned it was because it was haunted, but we didn't care. It was our

battleground and warehouse. You see, as well as splitting Coltart Road into two,

it was also our foothold into enemy territory. On it we would build our

barricades of wood, bricks and broken paving stones, and dare the Coltart gang

to chase us off it. They only did it once when, unknown to us, the sneaky Mozart

Road gang made an alliance with them and attacked us from behind. Mind you, we

soon sorted their alliance out, when we declared all out war on them. We caused"

them so much trouble with ambushes, something we were famed for, that they broke

their alliance with Coltart Road and made one with us.

We weren't all that keen on an alliance, but they came in very useful for

collecting wood for us, or so we thought. We found out later that they had been

hiding most of what they had collected in their own secret stockpile. We all had

secret stockpiles. The wood in them was only to be used when the firemen had

been and put out the fake bonfires and gone away. Then out would come this wood,

and the real bonfires would blaze away all night undisturbed.

Most of the gang wars were caused by bonfire night. It was because of all the

work that went into collecting the wood and other materials to be burnt. And

there were quite a few ways of doing this. One way was simply to knock on some

one's door and look sheepish, as you ask them for the roof off their backyard

shed. Another was to be cheeky and say, "We hear you're getting a new couch next

week, can we have your old one for the bony?" Most people gave willingly,

probably just to get rid of us, but others, they wouldn't part with a used

matchstick. We had to use more devious methods with them. One of us. would knock

on their front door and keep them talking, while the rest of us pinched whatever

we could from out of his backyard.

We used to have it all worked out, you see. We'd walk along the backyard wall

and over the toilet roofs, spying out who had what. Of course, the best and

quickest way of collecting wood was to find out where the other gangs' secret

stockpiles were. This was often achieved with bribery. A packet of sweets won

many a wood war on the day. When a hideout was found, we'd keep a watch on it

until all the members of the gang it belonged to had either gone in to watch

telly or to have their tea. Then we'd pass the word around and move in quick. It

often took days to build up a good supply of wood, only to have it all pinched

in minutes by another gang. But that was all part of the wood war, and we

accepted it.

Anyway, after a short confrontation with the Mozart Street gang, we got all our

wood back, and most of theirs in the process. In the end, we had so much wood

that we had three bonfires going on the night. We even let the Mozart Street

gang watch them with us, and it wasn't long before the Coltart Road gang

infiltrated their way in. Yeah, we had won the Wood War that time, but somehow

it didn't seem like a victory any more. It was more like the coming together of

the gangs. The warring was over and the bonfire nights that followed never

seemed the same again.

And now, grown up, married, and living on a new housing estate, I recall those

days with a smile. Of course, we didn't realised how dangerous the things we got

up to were, to ourselves and to others. But that's the way of life, isn't it?

It's only those who have lived through such events and survived to look back at

them, that realise how dangerous they really were. But at the time, they were so

much fun.

And you know, it saddens me, not to have kids knocking at the door and then ask

if they can have our couch.

John Walsh is a member of the Runcorn Writers' Group, which is planning to

apply for membership of the Federation of Worker Writers.

HOW I BECAME A SHOP STEWARD

Tom Durkin

"There is a tide in the affairs of men" - so wrote Mr. Shakespeare, many

moons ago, and went on to explain how, by rising to the occasion, completely new

prospects open up.

Well, the tide occurred for me in the mid-thirties, when I was a poor immigrant

chippy, seeking the Holy Grail of work in depressed and slum-ridden England.

After months of searching, fortune smiled on me and I got a job.

It was a slave labour building site. Workers were being sacked at all hours of

the day and other unfortunates were ever ready to jump into their shoes. There

was a semblance of union organisation on the job.

The labourers' steward was a young and slightly built fellow, but what a brain

he possessed. There wasn't a thing about union history, structure and agreements

that he didn't know about. I often wondered how the head of any human being

could contain such knowledge, and expected that on a hot day it might expand and

explode like a bomb, scattering brains all over the place.

This day, the poor navvy slaves were digging a trench with water and sludge

almost up to their knees. The stewards asked the navvy ganger, an uncouth bully

and brute, to provide them with rubber boots.

"They're not here to picnic, but work," he roared, but later came back with a

load of old rubber boots, caked with mud and cement that had made the

acquaintance of many different feet in their time. "Get these on you, and lets

have some work, you pack of idle whores," he shouted, as he threw the old boots

on the bank.

The navvies scrambled out of the trench to put the boots on but the steward

intervened. "They are entitled to an extra penny an hour for wearing rubber

boots in water or concrete," he said to the ganger. It was as if he had asked

for the keys to the gold vaults of Fort Knox.

"A penny an hour more. Perhaps you want diamonds. Don't you know the jobs in

debt?" (That was the usual excuse in those days.) "They'll get no penny. They're

bloody lucky to have a job, and if they don't like it, there's no barbed wire

round the gate. There's plenty of good men outside looking for a job."

The steward told the foreman that the extra penny was part of the Working Rule

Agreement, and that unless it was paid the men wouldn't wear the boots or work

in the sludge. With that, the ganger, who was a strong arm merchant and had

.often previously lashed out at a worker, let fly a sudden right-hander and

flattened the steward in the mud. Then, like a mad beast, he bent over him and

tried to throttle him to death. He was plain berserk, and it took a couple of

the navvies to drag him off the steward, who was covered in mud with one eye

almost closed.

This was the spark that kindled the long simmering discontent. The slaves

rebelled and stopped work. It was about an hour to go before knocking off time,

and a meeting was held with the brickie steward, an old timer, taking charge.

No one really knew what to do next, and it was agreed that union organisers

should be called to the site for a meeting at starting time in the morning. The

brickie steward advised all trades not organised to hold meetings and appoint

stewards before leaving the site. The chippies held their meeting.

Many, like myself, were not in the union, and no one wanted to be steward, for

that often meant being first to "go down the road".

"What about you Pat?" said one of the chippies, pointing to myself. Then some

others joined in to put poor Pat in the hot seat. "Jaysus, what do I know about

being a steward, sure I'd only be a great omadhaun" (a gaelic word for a fool) I

answered, as scores of eyes focussed upon me.

"Go on Pat, have a go, the ganger won't try to lay a hand on you, 'cause you're

too big," they said by way of encouragement. "Jaysus, sure I couldn't make a

speech of nothing and anyhow to be a steward here would be like putting the

noose round my own neck. I'd be down the road on the very first day."

But it was no good resisting. Through a combination of praise and flattery and

opinions that the ganger was just a bully and coward who would be too scared to

raise a hand to me, I was press-ganged into becoming a steward.

On the way off the site, the brickie steward asked me what the chippies had

decided to propose at the meeting in the morning. I said that they had decided

nothing, only that I should be steward. "You must be on the platform in the

morning when the organisers come to report on the chippies meeting," he said.

"Holy Jaysus, sure I've nothing to say. I never spoke at a meeting in my life.

I'd only make a fool of myself," I answered, as the enormity of my

responsibility hit me and the thought of not coming in the following morning

began to take root. I was torn between the temptation to bale out so as not to

make a fool of myself, and wanting to back the steward that the ganger bully had

laid low.

On the way home from the site, my mind was in turmoil. I knew I would have to

say something at the meeting. I cursed myself for being such a thick and

inarticulate idiot and for all the time I had wasted in the village school when

the master, John Igoe, tried to knock some knowledge into my wooden head.

"You're as thick as the nine folds of a sack. If you spent less time blethering

and playacting, I might be able to knock something into your thick skull," he

would say as he belted me round the lugs.

Suddenly an idea occurred to me. I would go into the public library near to

where I lived and ask if they had any books of speeches made by stewards at site

meetings.

When I asked the library attendant, she looked at me in amazement, so I blurted

out my problem. "I have some books on public speaking. They might help you, but

as you're not a member you can't take them away. If you wish, I will let you

have one to study in the reading room," she said with some sympathy.

Desperately I leafed through the book, but there wasn't a single speech in it

made by a steward on a building site where a navvy ganger had beaten some one

up. There were plenty of speeches suitable for all kinds of events such as

elections, public meetings, dinners, conferences, birthdays, marriages,

funerals, in fact for every conceivable occasion except a site meeting.

Many of them began with "my lords, ladies and gentlemen; your excellencies" and

similar phrases. I felt they would be somehow unsuitable for the building site,

and handed back the volume, which was written by a gentleman named Theodore

Arnold Cowes-Blake, DPh, OBE, who apparently forgot to include stewards'

addresses at site meetings.

I think I spent the most tortured night of my life mulling over what I should

say in the morning. I recalled the labourer steward always starting his speech

with the phrase "Worthy Brothers," which sounded very impressive.

But what to follow, that was the question. I was like a man who had never

climbed more than a little hill setting out to tackle Everest.

Like a man in a daze, I mounted the canteen platform in the morning with the

organisers and other stewards present. Every pair of eyes seemed to be staring

directly at me, waiting with sadistic expectation for me to make a fool of

myself.

The brickie steward opened the meeting and introduced the organisers. Then he

called upon the aggrieved labourers' steward to recount the previous day's

experience. He started off as usual, "Worthy Brothers", and without a single

pause or hesitation told about the conditions of the trench, the boots, the

extra penny an hour as laid down and how the ganger assaulted him. He had by now

a real shiner on one eye, which was almost closed, and this aroused much

sympathy and anger.

Then one of the organisers spoke, condemned the ganger's vicious attack, and

went on at length to refer to early days of trade unionism, when men were

attacked, thrown into jail, transported in chains, worked all the hours of the

day, had no rights until they began to form unions. "If the ganger gets away

with it, we'll have those days back again. We mustn't allow it to happen. We

must make a stand now," he concluded. We all listened to him with rapt

attention, and I thought that this speech surely merited inclusion in Theodore

Arnold Cowes-Blake's book.

Then the chairman said, "The chippies have appointed Pat here as their steward

and he will report their views to you." I was dumbfounded. I stood there and

opened my mouth, but no words would come. My mouth felt as dry as a straw rope

on a hot summer's day. "Jaysus pity me and give me a few words to say," I

prayed.

Then I blurted out, "Worthy Brothers." It seemed so strange and artificial in my

mouth, while it sounded like music when spoken by the labourers' steward. "What

are we going to do? What are we here for?" I shouted out desperately.

"Hanging is too good for the ganger. He tried to kill the steward just because

he asked for an extra penny for the navvies working almost up to their necks in

water. He should be drowned in the trench like a rat. If he raises a hand to me

I'll shear his lugs off with my axe. I won't stand any of his bullying capers.

Jaysus, I won't. The steward was speaking up for us all, so he was, and well

able to do it he is too. I don't know why he works here at all with all that

education in his head. He should be a professor. The bloody ganger is pig

ignorant. He doesn't know his arse from a hole in the ground. Lets all go into

the office and demand the ganger be sacked for attempted murder. Lets bring our

shovels and hammers in and wreck the office if they don't sack him. The firm

should be proud to have a man like the steward working on the site."

The chairman was looking at me as if I were stone bonkers, and said, "Thanks

Pat," to shut me up before I would try to send the workers on the rampage around

the town. But a lot of the workers cheered, although they didn't agree with my

mad proposal. A few of the firm's stooges began to sneak out through the back

door so I hollered out, "Look at them slimy bastards sneaking out to tell the

site agent what we're saying. We should run them off the site."

Following on my wild outburst, there were a few restrained and statesmanlike

speeches made by others, and it was agreed that the stewards and organisers

should go to the office and demand the removal of the ganger from the site.

The management refused to remove the ganger, who claimed that the steward was

rousing the other men against him and trying to humiliate him with big words and

quoting agreements. He came out with the old tale about the job being in debt

and in danger of closing down. Then all would be sacked and far from being a

bully he was really a benefactor. He kept harping on the steward using big

words. "What's wrong with him using big words? Are you afraid he's going to wear

them out? You've got no words, only swear words and abuse," I shouted at him.

After a lot of wrangling, for almost two hours while the men sat in the canteen

playing cards or drinking tea, the ganger agreed that he had lost his temper and

apologised to the steward. It was also agreed that the labourers would get their

extra penny for wearing the boots in the sludge and while levelling concrete and

that other problems would be discussed at a later date. We hadn't a snowball's

chance in hell of getting the men paid for the time lost in the stoppage.

When the officials reported the result in the canteen, there was a great cheer

of relief. One or two said the ganger should be sent down the road and that he

was certain to try his rough stuff again. "If he does, let him not try it on me

or he'll have no lugs going home," I shouted out, but the chairman curbed me,

saying "Leave well alone, Pat, we've shown some strength today because we've

stood together. That will make him more cautious in the future. Unity is our

best weapon, lad, as you'll learn with time."

All the doubts and misgivings of the previous night had now evaporated. Here I

was, a steward and feeling ten feet tall. "You're a wild bastard from the bogs,"

said a few of the others to me afterwards, and I realised that there was a lot

to learn in the business of shop steward. I am still looking for that book of

speeches by shop stewards. Perhaps I'll get down to tackling it myself one day.

Tom Durkin is secretary of Brent Trades Council. He has had other work

published by London Voices.

STRIKE

Joan Batchelor

At first there was sympathy, the "I'm on your side..." manner. Then

impatience crept in. And a certain desperation. "On the books please," but no

money ever changed hands, so the shops stored less and less, selling things

singly. One candle, one egg, two ounces of tea. "Sorry, money down. We too must

live, you know."

The coalman "forgot" to call, the breadman rode past, the milkman paid delivery

boys in milk and orange juice. Vegetable gardens were ransacked, wild plants and

herbs bravely eaten. Stews made over low fires with scrubbed peelings and the

odd skinny rabbit from the sparse hills. Clothes were mended and exchanged.

Shoes stuffed tight with cardboard.

The word would pass along the houses. "The rent man" or "the insurance man", so

women hid and shushed babies, while rumbling turns gave them away.

Like black ants on the slag tips, children made pickings for the fires, proudly

carrying home the spitting fuel. A nightmare was the white, uncovered face

buried under a wall of shale, the little bag of fuel still in his small fist.

And a mother howled, shawl over head.

The men held meetings in the pub, totting up beer on the slate. Feelings ran hot

and high, and deadly tired women bore the weight of many a fist. Beer on an

empty stomach, and good money spewed into the gutter while women wept. The

doctor's surgery was packed with bruises, and terror in the guts, causing pain

and discomfort.

"Have you eaten, cariad?"

"Well, of course boyo, no good waiting around for you, is it?"

And sunken, hungry eyes watched each forkful stuffed into her man's mouth with a

sort of wistful satisfaction.

Grandma's on the pension saved oranges and home-made goodies to be stuffed under

their daughter's apron. "I'll eat it later mam..." (to be saved for the children

after school).

Skinny, shabby women with haunted eyes, ballooning with yet another pregnancy,

watched for the gas and electric vans, surrounded by small, clinging, silent

kids. Writing apologetic, painful letters, pleading, tongue between teeth, nose

to paper, head-office jokes. A swallowing of a pride far bigger than their

swollen bellies, smacking children who felt their fear, wearing leaden weights

about their hearts.

The chapels filled. A good hymn made lighter the day, for entertainment at home

was the beer-sloshing bellies against their own and yet another mouth to feed.

There was always gossip, with the true story-telling of the dramatic Welsh.

Sitting on the doorsteps, babies in shawls tied tightly under limp breasts.

The abuse grew.

"Get yer loafin' man back to work, missus!"

Daily were the fistfights of the men and the shrieking, no-holds-barred, of

women. With their hair unpinned, rolling in the mud, as wide-eyed children

watched in wonder.

Dog fights were betted on in fag-ends. If a maggotty sheep or two went missing,

blame it on the black, watchful crows, but good was the smell that arose from

the black pot bubbling on the hob. And mouths watered, dribbling.

The nights were split by quarrels.

"Come on girl, you 'ad the family allowance today an' my blutty slate is

full..."

The few shillings already filling their stomachs and the purse empty and flat.

Morning brought out the cut lips, the purple, swollen eyes - then the men would

say, "She spent the lot, the bitch.'"

Sympathy brought full, foaming pots for a while.

Later, desperation faced the pickets and were well beaten back. Windows smashed

and doors daubed, "Filth," "Blackleg," "Scum", "Traitor", all equally cursing

the unions inside, paid and smug they were.

The final wage increase did not cover the idle weeks. And so it went on and on,

never quite getting it straight. The men celebrated, but the women wept for the

debts of those lost weeks.

Joan Batchelor was born and bred in South Wales, where her father was the

village policeman. She has had a book of poems, ON THE WILD SIDE, published by

Commonword.

CAR FACTORY MUSIC

Michael Butler

MACHINES

Shut up your noise, listen to us.

Watch our wheels keeping time,

pouring the parts out to the cars,

even flow, steady feed.

We are the ones set you the beat –

stick with us, play our notes,

rhythm to fit - why d'you complain?

Just comply, take your wage.

Point of the job? Let it alone.

Method, speed? We decide.

All of your lives, same as in here,

drawn on boards, made to type,

live in the ways all of you know.

Why invent, dream to change

what you'll achieve? Keep to the plan,

run like us, screwed on base.

SOME MEN:

Yes, we'll oblige you, yield while it suits,

we're live machines locked to your hold,

bend at the rate the dials have set,

all tuned and timed, fitting your pace,

follow and serve as long as we're switched,

with wages' force opening valves.

Money'll suck our energies out,

and pipe them up, blend them with yours,

set them to work, and filter our choice

and push our thoughts covered from sight

-most of what's living carried below,

compressed and sealed, cramped in the gut.

Out of the gate our wages'll bring

some room to move, free of the clock,

time to uncan our life from the tin,

and pour it out, filling a glass.

Every container shaped like the next

I'll hold it safe, hidden till then.

OTHERS

Workday after day, fixed on an unchanging track,

rammed in a routine, twitching in the moves it set,

limbs worked and our brain slept.

Suddenly a stock injury, a common wrong

flashed across the stale gases of the choking hours

stored up through the long year.

Now we've come awake, shaken by the blast, we'll fight,

shatter every bolt, loosening the rigid rails,.

spring clear onto free ground.

Out of here we live, breathe,

weigh moves, can pick out a path,

his or that. We start, stop,

turn, linger, follow it through,

loose a while, to change speed,

clear space and level our way.

Watch between the piled bricks,

blocked concrete, traffic and gas,

trees against the grey walls

sprout leaves and shake in the wind,

spread towards the sun, teach

men, too, can branch in the light.

Racing horses, caged dogs,

bolts, drawn, ‘ll break from the start,

rush and jump. Their stored strength,

freed, flies through gates to the course.

We're like that at day's end,

cramped minds uncrease in the air.

Long as we're here, we're clamped, bolted,

tied, there's no choice taps our energy,

nothing'll use our minds, carry

current away, make or build with it.

Strike, then - we'll jump the gap,

power

leaping across, fuse machinery,

smash all the blocks they've laid, leave them,

cut all the rules, ropes to tangle us,

fight while the flame's still high, push them

back with our strength, fill the

vacuum.

Michael Butler is a former worker priest. He has worked as a

labourer in France, Portsmouth dockyards and in North Acton.

LETTERS

Write About It

Dear Voices,

I've been looking at the August edition, and it seems that Mike Kearney's review

of the WRITE ABOUT IT anthology from South Wales might deserve some reply.

Firstly, as Mike quite rightly points out, the funding of the project was

assembled from a variety of different sources by Sue Harries on behalf of the

Welsh Academy'. He complains that there was no 'political strategy'. I think it

requires considerable ingenuity and a very sharp strategy indeed to raise money

to run writers' workshops for the unemployed. Funding bodies in general are not

particularly interested in funding the revolution - at least not in this part of

the country!

The initiators of the project recognised their lack of experience from the

outset. That is why they wrote to Ken Worpole who suggested that Ian Bild and

myself might be asked to help them out. lan and I were able to introduce a

number of modifications to their ideas, to bring the workshops more in line with

normal Federation practice. However, the idea never was to produce 'socialist

working class literature' as Mike expresses it. The project was not set up for

that reason and we would have achieved nothing if we'd attempted to hijack it.

Finally, I'll come to Mike's rather abusive tone. As far as 'unemployed military

with ingrained reactionary prejudices' go, I should have thought that quite a

large proportion of working class men fall into that category - or is Margaret

Thatcher only a figment of my 'middle class jerk' imagination? One of the most

interesting political phenomena of this end of the 20th century is the

increasing politicisation of those 'petty bourgeois' horrors the white collar

workers, who are in the process of realising that even nice people get thrown

out of work. So far, none of the South Wales groups have affiliated to the

Federation. If they read Mike's review, they probably won't. That's a terrible

shame. I found it a privilege and a pleasure to work with them.

DAVE POLE, BRISTOL BROADSIDES

SW NEWS

The third of a series of one-day regional meetings between South Western member

groups of the Federation and other writing groups in the area, took place at the

Women's Education Centre, Shirley, Southampton, on Saturday 24th September.

Apart from the hosts - members of the Women's Education Centre who have produced

various publications but do not currently have an active writing group -those

attending were from Bristol Broadsides, Word & Action (Dorset) and a writers'

circle from New Milton in Hampshire.

The arrival of this latter group led to some interesting exchanges of ideas

concerning the Federation's approach to writing and publishing as a locally

based, community activity, and that of writing with the intention to be

published in national magazines and the like, earning an income.

The morning was spent with the thirty or so people at the meeting reading from a

variety of work of an impressive range and quality. In the afternoon we divided

into three workshops to discuss approaches to criticism of one another's work in

writers' groups; the value and experience of women writers' workshops; and the

general subject of poetry.

The next of these meetings will take place in Dorset at a date yet to be fixed.

Although a number of other groups in the South West had been contacted with

regard to this meeting, disappointingly, none of them came. If any readers of

VOICES in the South West are interested in coming to the next meeting, contact

myself, Dick Foreman, or Stewart German at Word & .Action (Dorset).

Finally a word of thanks on behalf of everyone attending to the Women's

Education Centre for organising the meeting and providing excellent

food throughout the day.

DICK FOREMAN, DORSET

MYTH & REALITY

Dear Voices,

You may remember that in your number 28 you published a letter of mine on a

writer's commitment. I've been doing some additional thinking since then.

Like, I believe, a lot of our writers, I find myself in a kind of cleft stick: I

want to latch onto things as they are (well, some of them). I don't want to

derail into fantasies. At the same time, 'things as they are" at the moment are

not exactly edifying, and it's very easy to turn into a bitter, purely negative

writer or into a facetious 'wit'.

I've just finished writing, a very short story about a happening I witnessed: an

old man, suspected of begging, being thrown out of a caff. And only after the

third attempt did I realise that I'd hit on where it's 'at': the gulf between

the poor and the not-quite-so-poor. But, to set something against the sheer

immorality of indifference, I found myself falling back on moral values that

would still find a resonance in our imagination. I made the old man 'look-alike'

God-the-father (as in popular pictures). But it might just as well have been

Odysseus disguised as a beggar, being pelted with bones, or Harun-al-Rashid, or

any other myth that uses the expedient of disguise to by-pass reality and get at

our pity and guilt.

But has our imagination been so flattened and cheapened that one has to fall

back on these ancient tricks? Of course, I could have twisted reality and

introduced a Robin Hood figure (the only anti-hero still living in popular

imagination). But that would have been a twist. True, I may have chosen an

unsuitable background - a caff in London NW1. But would matters have been

different in a Durham working men's club (where they don't admit coloured

workers)? No wonder the two most powerful protest works in recent years have

been steeped in mythology: Marquez' "One Hundred Years of Solitude" and

Rushdie's "Midnight's Children".

Anyway, going through with this very short story has made me realise:

One: the need to get hold of and grow clear about where it's 'at', where the

shoe pinches, however painfully and shamefully.

Two: though we can't have recourse to any ready-made myths, we still have to

weave our stories between what is and what could, might, should be - to affect

the; imagination.

LOTTE MOOS, HACKNEY

BYBYE FIDO

Dear Voices,

After several group discussions, we thought it about time that some one said

something about the logo design which appears on the back of the journal. First

of all, the dog strikes us at a glance as being overly aggressive and ferocious.

Perhaps this is designed to lure the public into purchasing a copy of VOICES,

but the message could easily be read as "subscribe or else". Secondly, ferocious

dogs in many people's minds, mine included, are associated with fascist

symbolism (i.e. the Nazi's use of Alsatians and the National Front's use of the

bulldog). Last, and perhaps more peripheral, is the issue of the use of

Alsatians which has accompanied "community policing" in Hackney. I think that

what this adds up to is the employment of an illustration which represents the

opposite of what the Federation stands for. I think that such a drawing has no

place in VOICES. I haven't come up with any specific alternatives, but I'm sure

that with a little imagination a logo which is more representative of the

ideology and aspirations of working class writers could be devised.

COLIN SAMSON

on behalf of Hackney Writers' Group.

Dear Voices,

My son Ian wrote this poem after being

on the dole for a year.

Ian is twenty-four now, and the eldest of my four children. He was always very

class conscious at school because although my husband has always been in full

time employment the children were all entitled to free school meals.

This meant standing in a separate queue so that everyone knew who the kids were

from low income families. Nevertheless, Ian regarded education as a right for

everyone, and went on to gain a B.A. degree.

Unfortunately this did not help to get employment. The D.H.S.S. were continually

on his back, and in desperation he has accepted a teaching post in Algeria. It

was his request for some "revolutionary poetry" which led me to the DAYS OF HOPE

bookshop in Newcastle, where I found some suitable material for him (and me!).

The assistant was most helpful and I look forward to returning for future

issues.

Yours sincerely, Mrs. C. Colley

Letters have all been cut this time, due to lack of space.

CLAIMS

Ian Colley

Who are the spongers?

You sit there in your knife-edge security

and talk knowingly of false claims.

They, the state, have claims,

they rule you they fool you,

they shoot you "they feed all"

If you let them.

They, the poor, have claims, they need food, houses, lives.

If that's all right with you

who don't like their faces.

You have claims, you claim to be a worker.

All your life you have generously worked for

some one else,

and given them your hopes.

Now they have given you claims as your thro-away

rooms send you out to work in the approved manner,

Will you reclaim your life?

Is it for this labour martyrs suffered and died?

You, a reasonable, sensible chap, will report

to the appropriate office and give

box numbers and particulars,

You won't make any false claims now will you;

WILL YOU?

COMMONWORD WRITING

I will try to explain what being part of Commonword means to me and what it

could mean to you who are writing and doing as I did, before finding

Common-word, putting your work into plastic bags or cupboard drawers.

We are comprised of several writers' groups, mixed, women and gay.

When I first came to Commonword to read my work, I was brought face to face with

the simplicity of my writing and my inadequate use of language. After three

years or so with the help and constructive criticism of other writers, my

writing has greatly improved.

I belong to the Monday night group, which is a mixed group of men and women. We

read our work, then discuss it, criticise it and if it's good enough publish it

in our magazine WRITE ON. The other groups are run in much the same way. The

groups fluctuate in size but there are new faces at most meetings.

The standard of work is quite high and many of us have already had work

published, either in VOICES or WRITE ON. We have also published many books of

individual writers and several anthologies. And, as if this isn't enough,

readings are organised throughout the Manchester area.

If you are interested in reading more of our work, or joining one of our

writers' groups, contact us at COMMONWORD, 51, Bloom St., Manchester M1 3LY.

Tel. 061-235-2773.

ALF IRONMONGER

Alf is an ex merchant seaman and steel erector. He started writing after he

finished work, following an industrial accident. He's been a member of

Common-word for five years, and serves on the executive of the Federation of

Worker Writers. 4 Community

DEATH OF THE HOBOES

Alf Ironmonger

They rode the rods

The silly sods

Across the Nullabor plain

They didn't know

They'd never see

Old blighty once again

The stones jumped up

From the tracks

Scarring their poor

Aching back

For them it did

Not matter

The yard dogs

With rope and chain

Knocked their bodies flying

Beneath the wheels

Of the train

They lay there

Slowly dying

Taken from Alfs AN

AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL, 60p +

20p postage from Commonword.

WHY CHANGE?

John Gowling

I got the idea for this story from a newsreel on Poland, but reflected it

back to my own life, relationships at work, and the economic depression in

England and Wales. I feel that both nostalgia and change are double-edged

swords.

You are awoken by the pigeon as it flutters off the wire which is attached to

your bedroom veranda. The wire starts to whistle as you open your eyes to focus

the condensation on the window.. The train rattles past, then moans up to the

terminus at the end of the street. The thought enters your head that it was not

yesterday but merely hours before that you drank with you brother and his

friends at the bar. You are still heady from the beer and although it is a

geographical fact, in itself each new day is no longer a revolution, it is a

part of a continuous term, a sentence for each life, ending in death.

Your hair in the mirror - the front parts are grey, the parting recedes exactly

like those men you'd observed as a youth. Today's preparation consists of a

swill under the tap, a glass full to bring the body back and generate the first

gut action of the day. And the clothes that don't smell too bad, but are already

ruined, they'll do you for work, they still wear quite hard.

So relock the padlock, descend to the street, and wait for the tram. Observe the

broken lino of your lobby from across the cobbled street; the porch door is left

open for the bread-man. Your tram rattles up like three broken food cupboards,

or old redundant wash boilers. Climb up its slimy running boards to aside the

driver. Bend your card and clip it into the machine -National Strip Card,

interchangeable for one week. It makes you no less guilty - punching it

correctly, the driver looks over his shoulder to check everyone is not cheating.

A conformist or ritualist is no less a cheat for it is he who will expect

something, some order, some inner peace, for following the rules. As the tram

pulls off, the clatter becomes the varnished woodwork, the seats tired past

splintering, which will become soft and sticky in the hot afternoon, but now are

hard and fresh like this morning's newspaper stories as the economy slides from

worse to a new level of coping: it is the food, producing the food, the wines,

the beers, the medicine, the stones, the bricks, the roofs; it never changes,

yet the coping becomes bolder as things slip from bad to worse.

And now at the coalyard, the heap of dusty trains, you ash out the boiler, cough

but the pains. And spit clear of the rust, for you don't have to be told this

machine has got to live out its redundancy, like the towns and the fields, and

us. And heap up the ash, don't look over your shoulder, don't listen for him,

he's come soon enough. Close your ears to his sickening yawn. Swallow, don't let

him know that he makes you feel sick. Don't even smile, you know he can't abide

creepy behaviour, just work on in silence, and stubbornly reach for peace. A

moan of recognition from deep in your throat tells him you can work, but quiet,

alone. And tip out the ash to the barrow on the track. Sweep off the muck from

the footplate round his feet. Pull out that little tin of wax from your back

pocket and wink to him as you pull out the rag to rub that little hole of rust

round the top of that huge armchair shape that holds the coal.

Leningrad Street Scene

Chugging through fields, pushing two coaches up front, shovelling in silent

obedience. He hardly needs to speak, just to gesture. Rarely an emergency alters

the pattern. The railway and engines are hardware like the fields and factories,

should outlive this century and our lives. They are too expensive to replace,

and besides, they are so simple that there is nothing to go wrong. They were

built to perfection at your grandfather's works. They are cast and remoulded

until finally their frames break of fatigue. And you hating the driver 'cos

you're past understanding, you know it's just him and that's how he is, and like

you, he'll never change. A working relationship where novelty was brief, and

touches and smiles and seriousness and times, times between stations and times

in the yard and times of bereavement, and hands on hands, and foreheads on

hands, and tears on hands, and hands on rags which polish the grime, and time.

And marriage and christenings and times of change, and time didn't matter 'cos

it all stayed the same. His whistle on the engine, his whistle on the street.

And times at your flat and his rows back home. And like the smoke from each

bridge that hung in the cab, it never changed. And now like each morning how you

never speak 'cos there's nowt to discuss and it's all been said before. The

silence maintained till twelve o'clock in the middle town when he brings out his

curry butties, his voice like the train, a lifeline in time.

And there's flags and there's signals but there's only one train, that's up on

the down line and down on the up. You know, you could win a considerable amount

of money by suggesting they tore up one line. But with one line would go half

the jobs and all your friends. The train wears the lines in trim for better

times, but we've all got a job so there's no point to change.

And now there's the town at the end of the line - just a heap of old bricks

redundant in time. Time grown tired at the heart of the vale, resigned and

fateful, in a nutshell; stale, just waiting to die. Just an old square of

buildings trim round a church, with fears of abortion, sex, greed and sin; a

town full of drop-outs who never dropped in.

A town in which at a quarter to two a dog sleeps on a doorstep and waits for a

train that pants and heaves up the line bringing roof tiles and grannies, a one

train a day train.

John's gay novel, MARSHALL'S BIG SCORE, has just been published by Commonword,

price £1.20 + 30p postage.

HIGH LIVING

Ruth Allinson

Living up here on the fifteenth floor

I'm supposed to be lonely and sad,

But I have to admit that I like it -

No! I'm not completely mad I

Of course it's no place for children,

For mums at home all day -

Growing limbs need fresh air

And plenty of space to play.

But I'm not a house-trapped mother,

My family is full grown.

I look out on the spacious Pennines

And at last my soul is my own.

It's only a background to living

And most of my life's elsewhere,

But it's good to come home of an evening

And have time for myself to spare.

I used to be forever working -

Domesticity, garden, career -

Till I decided I'd had enough,

Packed suburbia in and came here.

Perhaps when I'm old and tired,

Feeling sedate and sane,

I'll leave the crazy heights of the

fifteenth floor

And come down to earth again.

Ruth Allinson is a Tightfisted Poet (see p. 23)

STAYING IN

Tommy Barclay

Your talk was bluff, everyday stuff.

The little shackles of marriage

Were rattled with the semi-whine

Of rueful complacency,

The identifying accent

Of the married man.

I made the appropriate noises

In the small spaces provided,

All the while wondering

Whether your wife had a name.

Titles she appeared to have in plenty;

Cook, Laundress, Housekeeper,

Mistress, Nanny, Mother -

But no name;

"Typical," I was thinking,

Then he walked by.

Young, lusty, long-legged,

Unaware of his earthy effect.

Your voice wavered,

Then regained its strength.

But fleetingly,

Longingly,

Naked at the windows of your eyes,

Your soul looked out

From its prison.

Tommy is a member of Northern Gay Writers.

LETTING GO

Bernadette Tweedale

Both girls smiled at Monica from across the damp

road.

"Why don't you put your umbrella's up?"

Each teenager gave a knowing, slightly embarrassed look to the other. Monica's

daughter smiled and cockily answered: "It's only a bit of rain."

"Where are you going?" Monica asked.

The two girls looked at each other, gave that smile, and her daughter replied:

"Oh, just out, I'll be back for half past nine."

"Think on then, 'cause I'll be back for nine thirty too."

Both girls looked across at Monica as she put her umbrella up. Immediately they

burst out laughing. Monica smiled then shouted: "Why y're laughing?"

"Have you seen the sight of you umbrella mum?"

"What's up with it?"

"Look at it, it's broken."

"It's not bad, it keeps the rain off. Do you want to borrow it?"

The girls smiled and burst out laughing. As Monica was walking away, they

shouted, "Wouldn't be seen dead with that umbrella."

Monica smiled to herself as the girls passed on. Her umbrella only needed two

bits of material fastening onto the spikes. But this mattered to them. She felt

a gap growing between herself and her daughter, yet she had enjoyed seeing her

with her friend, seeing that youthful vitality brim full. But as Monica walked

to her evening class she began to visualise her daughter's face. As the picture

became clearer, she saw that her daughter was wearing make-up. Well, that's

youth, they've to try things out. But why make-up? Well, she's fourteen, lads

will come into her life now.

Monica really enjoyed the evening class and what made it more enjoyable was that

she could go out now and leave her child - teenager - without feeling anxious

and then guilty. It was the beginning of a new freedom for her. Even other

nights she could go out now to see her friends or go to the community school

meetings that she was beginning to enjoy being involved in.

As Monica returned home she noticed that there weren't any lights on in the

house, and her daughter left lights on as though it was Blackpool illuminations.

Anxiety began to creep through her as she found all the rooms empty. Fears for

her child shuffled through her mind. She didn't mind her daughter being a bit

late. Remembrances of her own teenage years came back to her. Nearly always late

home. Always the question: where've you been, you're late. And always the

excuses. Her Carl-ton days, shocking pink layered net underskirt, pink skirt and

bright green ankle socks, jiving with girls to Buddy Holly's music, but always

with an eye somewhere else. Talking to her girl friends, yet waiting for

something. That waiting was a transition - a gap between child and youth. The

something became clearer to Monica. It was part of the waiting in transition to

the something - boys. Was her daughter ready for this?

A fiddling, a key. The front door opening. Her daughter entering the room, all

vibrant. Fears slithered from Monica's mind.

"You're a bit late luv."

"Oh, me and Sue walked back from Alison's."

"Well, try not to be late again. I get a bit worried for you."

After supper was over and her daughter had gone to bed, Monica pondered over her

daughter's reason for being late. Was she seeing lads? Was she alone with lads?

Was her daughter ready for lads? Monica didn't like this at all. Her daughter

might not have been at Alison's, might even have been with lads. Yet Monica

accepted her daughter living her own life. She's a teenager, she should have

some freedom, just like me. But Monica did not like these strange feelings.

Perhaps she should insist that her daughter be home for a certain time. And

should she find out who the friend was? No, she didn't like that. It was prying

into her daughter's personal life. A life that her daughter was starting to

live. She must trust her. But still.....

Early summer with light, warm evenings. Monica loved these long evenings in the

garden. She loved looking at and tending her plants that she had grown from

seed. She watched them thriving, stretching themselves into the air, their stems

and leaves haughtily, healthily green. She passed by these to the flowers. Her

young lupins she'd grown from seed three years ago glowed pink and deep blue,

full of vitality in their flower. She felt so pleased and satisfied with

herself. It was demanding work, growing plants, but it was worth it for her to

see them thrive. The evening began to cool slightly as dusk filtered the air. It

was peaceful, just lingering there at the start of dusk. Minutes passed. Monica

stirred herself, looked around and gathered up her gardening tools. Quite

satisfied with herself, she went into the kitchen, unscrewed the top of a bottle

of damson wine, poured herself a glass and sat down in an easy chair in the

living room. She sipped at the wine, lingering over each sip. Until... She began

to feel uncomfortable. Surely it was getting late. It must be half past ten by

now, and her daughter was not back yet. It dawned on Monica that her daughter

had said she was going roller skating with her friend Sue. Monica searched for a

clock. Twenty to eleven, it's too late for her to be out. She hoped that nothing

had happened. But she began to get worried. She forgot her wine and stood

looking out of the window, out onto the street, then at the clock. Five minutes

had passed by, but it seemed ages. Monica turned and walked away from the

window. She didn't want to be seen watching for her daughter to come hone, it

didn't seem to be fair somehow.

Another five minutes gone. Monica sat in the chair, drinking. She looked up

through the window onto the street and saw her. The relief, the subsidence of

fears, raced from her. Her daughter came into the room, looking bright, full of

youth.

"You're late tonight. I was so worried. Why are you so late?"

"Me and Sue went to the chippy and then walked back with some friends."

"Who were the friends?"

"Oh, just some friends from the roller rink."

Monica dreaded this, but asked, "Were there some lads?"

Her daughter looked at her with a half-concealed smile and questioning glance.

"There may have been."

"I do get worried for you, you know. I wouldn't like anything to happen to you.

But mum, I can look after myself, I'm not stupid. I'll try to be earlier next

time."

Monica smiled at her daughter, looked at her young, lithe body in the fitted

denim jeans. Her eyes moved up her tee shirt onto her daughter's mall breasts,

then to her lightly made-up face, her brown, sparkling eyes. Yes, her daughter

was growing up. Jo looked at her mother smiled and passed by into the kitchen.

More damson wine and hours later into the night, Monica sat there thinking She

loved those moments in the evening - seldom now though - when her daughter came

and sat on the settee with her They'd talk, her daughter would nestle up to her.

Monica's arm would stretch onto her daughter's shoulder and her fingers would

start playing with he: hair. But a cold, hard feeling nun Monica now. What if a

lad had done that to Jo, and Jo had accepted, liked it even? That couldn't be.

Not her daughter.

It was painful for Monica. She'd never thought of this before. But her daughter

was growing up. Why shouldn't Jo want this? She was the same as other girls. It

hurt Monica, though, to set a picture of a lad's arm over the shoulder of her

daughter. She fought on through the pain, saw sex, dismissed it, realising her

daughter wasn't read} for this yet. Monica now saw Jo as she had seen her

tonight, vibrantly testing tasting, exploring her own persona] life. That must

be, Monica thought, One day, sometime, she knew that Jo would talk about lads as

well as girls, She'd have to accept and wait for thai something to happen.

Bernadette is a member of Womanswrite.

BABYLON STATION

Carl Holt

There was no rain

and graffiti sat like a pain,

chained to red walls

and all the calls of a stillborn night,

faded to jaded hours

when everything was alright.

Black boys turned to black men

grown lithe again

to a hybrid beat of cushion feet

when thicker lips whispered ‘neat’

complete with eyes of another light;

that burned when everything was alright

Bastard children flickered fixed smiles

on shattered aisles

as midnight whiles through Babylon's stone parks

where, in a new dark

kid rockers ran thin fingers through a culture,

Like vulpine vultures, perched in the lowest heights

where khaki skin pierced like a pin,

everything that was alright

Now the quiet cars are purple with a sleepless haze

And a rusted memory of days raised from a grave

of paving and doorways

where towering dreams died in ugly ways

that was colour etched on stretched senses

staring through glass fences

left - then right,

land Babylon station burned tonight.

All hour every hour radio

smashed the repeated video

a hidden dream ridden video

where mono, stereo and quadraphonic sound

treads deep steps through shoe-box chasms

and rhythmic spasms call the shots,

when dawn is hot with a chilling blight

singing dumb songs that say alright.

Words pushing now like unconscious drums

beaten with tired thumbs

on an empty glass that was once stale wine

that passed heavy lidded time

when the light flamed too-too bright

and Babylon station burned tonight

ORPHAN IN THE HYPERMARKET

Ailsa Cox

"She's fainted."

"Put her head between her knees."

"What good's that supposed to do?"

"A slap between the shoulderblades.." So it was true. Here I was, flat against

some grey and slightly muddied linoleum. Apparently I had lost consciousness. I

opened my eyes on the world,, and the world made itself known to me - the world

of Nescafe, Weetabix, Bird's Eye and Winalot, as seen through thin wire mesh. A

trolley. My trolley. "It's alright," I said, propping myself against the wire.

Of course. It's always alright.

An eager face appeared before me. "Anything I can do? I used to be a nurse.

"I'll just sit here for a while."

"It's hot in these places, isn't it," she said, a handsome woman, strongly

lipsticked and on guard for necessity.

I kept still and safe.

"Not pregnant, are you?"

"Oh no." Of that I was, for no clear reason, absolutely convinced.

"Funny how it happens. Just lucky that I'm in the right place. Same thing

happened last week, you know. Poor girl had a miscarriage, right there at the

bacon counter." She looked at her watch. "Will you be alright now?"

"Yes thank you."

The huddle of well-wishers released me. I made myself at ease with my discomfort,

thighs stuck to 'the cold floor. It was summer. I was, it seemed, awake in the

centre of an enormous and ornate clock. Caught in the peace that comes with

rhythm, I observed towers of baked bean tins, empires of toilet rolls, and

nugget upon nugget of frozen vegetables, ice cream, beefburgers and cod. Each

detail was carved in full precision, for my ears in the ringing of till bells,

the clarity of muzak and mutter; for the benefit of my eyes, in the crystalline

colours of metal, glass and plastic. This was my cathedral, my civilisation -

whoever I myself might be.

"Security." Another face broken into orbit. I looked from the tight, grey

features to my own human hands. "What's the trouble?"

I was brought water, cold and clear in its triumphant nothingness.

"On your own, are you? Feeling better? Can you get to your feet?"

"In a minute."

He waited for a minute. "What can I do for you, love? How do you feel? Do you

want some one to fetch you?"

"I feel alright," I told him. "But I don't think I ought to leave until I've

remembered who I am."

"What do you mean by that, dear?" The more anxious he became, the more