|

ISSUE 29

cover size 205 x 295 (A4)

CONTENTS

THE HIGHEST COMMON FACTOR

Di Williams

One of the strengths of VOICES and the worker writer movement

is the breadth and wealth of individual experience reflecting the variety of

working class life throughout the country. This is important when the media (a

TV studio, for instance, which can create 'the thirties' with a few tell-tale

props) distorts the lives of working people past and present, pitching

themselves at a stereotyped audience, the man in the street, reducing the

working class to 'a lowest common denominator' .

The first time I heard this last phrase was at junior school when we had to

wrestle with some sums called LCDs. Whatever happened, I ask, to the next lot of

sums we tried, HCFs, that is the 'Highest Common Factors'? What are the factors

that good stories, poems, and articles have got in common? Without trying to pin

anything down about the words themselves, isn't it that they get through to you?

Something about them communicated something real.

To find out if a piece of writing 'works', and how it can be made even more

effective, reading by other people in a workshop is invaluable. Finally, work is

chosen to be published. For most of us, this is a new experience, to be a writer

in print. For many of the new writers in this issue, writing itself is a

relatively new achievement, as they have been adult literacy students.

As well as the hurdles of other working class writers - low confidence, a

literature and a schooling that has not answered their needs - they have had to

overcome yet another written language has been out of reach. But the degree of

difficulties and the experiences are so varied not to mention the people who

have them, that there is no stereotyped adult literacy student.

Some writing by students has already expressed the kind of alienation that they

have felt, and some ways they have had to conceal their isolation from those

with whom they work. But there are many non-readers (and not all literacy

students are non-readers) who have a great facility with the spoken word. Today

the oral tradition, story telling etc., is neglected as we put maybe too much

value on the printed word. A new reader, unfamiliar with the ponderous literary

phrasing of books, has a chance to develop a natural style and an original

approach. As a literacy student gains the ability to write what he or she could

already put into words, a lifetime's experience, struggles, humorous

observations and hopes, a writer evolves, needing some help with spelling like

most of us. Not all adult literacy students may want their writing to be shared

by others - at first the motivation may be simply to write legibly. But all have

got courage to tackle the hurdle for themselves, and to overcome it takes a lot

of bottle.

There is a danger that the spontaneity of expression, a potential wealth

untapped, may be lost unless control rests with the student. The workshop from

which the writing in this issue (see p. 5) has been taken has teachers, as any

adult literacy group must have. But they are particularly aware of the need for

the writing not to be teacher-controlled, as it may become under the influence

of teachers in many adult literacy classes. So the writing either takes the form

in which the student put it to paper, with some spelling help, or to help the

slower flow of words from halting expression, spoken words are 'scribed',

exactly as they are. Often a tape is used from which the speaker chooses what is

to be transcribed. The writing is chosen by its composer for selection by the

rest of the group of writers, for reading aloud in public and for publication.

The workshop, which is one held at Gatehouse, in Miles Platting, Manchester, is

run on lines similar to others of groups in the Federation. Gatehouse Project's

last report says:

"We are at present developing long-term writing workshops in which we join with

people interested in writing and who belong to literacy groups. The workshops

give people the time and space to enjoy writing and taping and to grow in

confidence about what they write."

In including writing from this workshop in the magazine, it should be judged by

the same criteria as other writing. This and future writing by adults who have

been 'new readers' needs a readership if it is to grow, as any writing needs

feedback. Does it communicate something real about the world of the writer? The

voices of those who have not been able to write need expression in order to

grow. The article in last VOICES from 'Write First Time' put it that "Those who

suffer in silence continue to suffer." The hurdles we have overcome to be

writers are shared in common with literacy student writers, and let us not

forget them. But also there may be much more shared in common when the best

expression of individual's lives comes to light.

Di Williams is a member of Womanswrite, a Commonword Workshop.

INSIDE THE GREENHOUSE

Steve Wingate

You worked hard enough -

So hard you forget you have.

Your body and mind both ache

For lack of exercise.

You live in this greenhouse now

Well fed, with plenty of light -

Conditions ideal for the growth of plants

But human beings need the windows left open,

Or at least the latches to the windows

Left within their reach.

And when friends become visitors

You have a sign on your face -

"NOT AT HOME".

By the end of the visit,

They think you've come to,

The signs removed.

But it's only you fulfilling expectations

And realising, by the weight of being visited

That this is as much a home as any was.

Steve Wingate is a member of Heeley Writers. He used to work in a

home for the mentally handicapped.

ONE OF US

Sue Gaukrojer

It was a short-stay psychiatric unit, an annexe to the General

Hospital. Harry had been there the longest of us all. Most of us were gradually

surfacing from our private hells, and, desperate for company, would gravitate

towards the charge nurse's desk, the focus of social intercourse in the ward.

There we would sit, many of us for hours on end, barely acknowledging each

other's presence, but taking comfort from a sense of it, in various degrees of

confusion and loneliness. Harry would sometimes shamble in our direction. On his

better days, he might laboriously lower himself into an armchair. He never

spoke.

Not that the rest of us were prodigal with our words. The nursing assistants

made heroic efforts to kindle a spark of interest or response. Their tone was

always kindly, and we had learned, like submissive children, to enjoy the secure

dependence of our social roles.

Elsie, for instance, just emerging from the self-imposed starvation of the

chronic anorexic, clung gimlet-like to her corner seat, as Megan, the staff

nurse on duty lectured her: calm and loving and threatening.

"That was another lovely porkchop Albert brought you last night. He's very

worried about you Elsie. He'll be cross with you again if we tell him you didn't

eat your dinner. Now what are we going to do with you? You do want to go home

next weekend, don't you Elsie?"

"Yes", said feeble, terrified Elsie from her heart, clutching for life itself to

Megan's eyes. Elsie was putting on weight now, but still so thin, she seemed to

have less flesh than blood, red purplish blood coursing through veins to

red-rimmed eyes and red-rimmed finger nails, and still at every meal-time,

rigid, she was coaxed and threatened through every mouthful of food.

"I thought you did." And Megan turned away, smiling. Elsie was stranded again.

White-faced, pathetic, fortyish, waiting for supper, waiting for Albert's visit.

In violet crimplene and black bouffant hairdo: the effort at survival.

Next to her was Gladys. Stalwart companions, they bunched together sheep-like on

the minor activities that constituted the hospital day - the trips to the shop,

the distribution of pills, the regular meals and coffee breaks. Gladys was on

the mend again: at first she had needed two nurses, one behind and one in front,

to push her donkey-stubborn to the toilets; now she could go on her own. The

shaking had stopped; she had knitted a dishcloth in therapy last week and was to

go into town on Monday.

Not so, the pasty, aging, joyless Doris. "I won't get better dear," she

announced, unshakeable, between cigarettes. It became a battle of wills. "They

don't know what they're doing," she would insist cheerfully, and to prove it,

she sat there in gloomy silence, glaring it out, incurable. Occasionally, when

they got tough with her, she would grudgingly make a token concession, agree to

have her hair done.

But she always had the last word. "They don't know what they're doing dear," she

called spitefully down the corridor, "I won't get better", the parting shot of

the sulky child.

Arthur was more forthright in the expression of similar views. His early morning

cry rallied the whole ward, "Bugger the bloody place", and stirred even the

gentle Miss Grey to a hissing display of anger. Arthur was confined to a

wheelchair, incontinent in every sense of the word, given to violent displays of

temper, unable to control language or bodily functions, his words coming out

with wild jerks of a badly swollen tongue, his pyjama flies permanently undone.

He slept a lot of the time.

But even Arthur raised his head and curbed his copious spits at visiting time.

They fastened his dressing gown, gave him teeth and combed his hair. He sat up

expectant, for one night last week they'd brought his new born baby nephew in to

see him. "A new baby," he said, cradling it, marvelling. But then the joyous

mood dissolved, he coughed up his phlegm and handed the baby back to his father.

"You can have that baby for £60,000," he informed the ward thickly.

Elsie's Albert never failed her. Bursting with red-cheeked health, he made his

brisk and cheerful entry on the dot, goodies for Erring Elsie in a carrier under

his arm. A neighbour had come to see Gladys. They sat there in nervous silence,

alarmed at Arthur's hideous, spluttering closeness. Chat was desultory: visitors

talked quietly, spasmodically, emotions suppressed, searching for words, faint

gestures across measureless distances. This was our life-line.

But Harry waited in vain. At first, we did not realise he was expecting his

brother. Harry never had visitors, and as he lumbered, glazed and trembling

round the ward, gripping the walls aghast, we had learned to expect none. He

seemed a special case, madder than merely mad, entirely isolate, staring

terrified sleepwalker.

But then Miss Grey pointed it out: Harry was crying; that shocked and tortured

frame had still some breath for gentle tears.

"Never mind, Harry", and Megan patted his hand, "I expect Cyril is working

nights."

Harry was bowed, still weeping.

That night he came to my door: he stumbled in, wild sunken eyes unseeing. Taut

fierce I turned him out, frightened at such a need. I shut the door, prayed for

deliverance. I'd never prayed before.

The next day was the last amongst us. I wondered at first if he was picking up.

At least he seemed to be talking. There he was, more determined than usual,

negotiating the corridor less blindly. But then I heard the manic cry and knew

the worst.

"I want a Mars bar," he told the charge nurse urgently. "I want a Mars bar," he

raised his voice.

"Shh Harry dear. We'll get you one."

"I want a Mars bar," he screeched it out, wheeled round in our direction, lunged

towards us. "I want a Mars bar."

We all resented this, the unpredictable. We bore with Arthur's early morning

tantrums, we listened unperturbed to Doris' ravings, but this was unexpected.

Harry we knew as docile.

"Shut up," Miss Grey hissed, vicious.

"We heard you the first time," snarled clever Doris.

We kept our distance.

Sadly he turned away. They led him back down the corridor, his incantation

quieter now, a dying song.

Those were the first and only words we heard him say.

That teatime they let him loose again. "Doesn't Harry look smart," said Megan

tenderly. "He's going out today."

He was wearing his Sunday suit, strangely incongruous after those weeks of

hospital pyjamas.

"You going home, Harry," came the envious cry across the ward.

"Cyril coming to pick you up?" suggested Gladys.

Harry kept silence now; his suit lent dignity, concealing a human wreck.

We watched him to the lift, his suitcase following. He did not say good-bye.

Like us, he had not understood.

"Never thought he'd be the first to go," we said, alerted, insecure. Why was the

door still closed on us? "He must be getting better."

"Oh no," said Megan. "He's not gone home. Harry's too sick. They've taken him

out to Broadfields. He'll be happier there."

We stared at the floor, our thoughts unspoken. He'd been the longest here, the

first to go, and not back home. What about us?

"That's terrible, Lord," said Arthur.

Sue Gaukroger is a member of the Gynerate Collective of women writers. She is

also part of a publishing project involving old people in the village where she

lives near Stoke On Trent.

LAST FRIDAY

Robert Hamburger

Blackshine taxi took her to that home

it was for the best.

She saw crowds in a mirror

hardly knows she's gone.

I will have her tablecloth four chairs

And a snap of my face as a child.

She can't understand who I am.

Confused among her visitors

With a moon to blank the window

and warm clothes

She's better off. We stay here

shutting rooms

Unhinge her empty mirror

carefully.

Robert Hamburger is a member of Basement Writers.

OLD AGE

Josie Anderson

Bewildered eyes

Sagging flesh

Nasty smells

loss of dignity

gratitude

is it as bad as it looks

this dependance, we won't

know until we are there

Josie Anderson is a member of

Gatehouse's women's writers group.

THERE HAVE BEEN WORKER

WRITERS BEFORE

Ken Worpole

There have been worker-writers' groups before. Yet sadly we

know very little about them. A recent conference organised by Andy Croft, a WEA

tutor and Birmingham University Extramural Department, gave a detailed, picture

of a group of working class and middle class writers who met as a group in

Birmingham in the 1930s. They were known as 'The Birmingham Group’, and

consisted of Walter Allen, Walter Brierley, Peter Chamberlain, Leslie Jalward

and John Hampson.

All of their work is out of print, as is so much important working class writing

of previous generations. Conferences or day schools such as these revive our

interest and increase the pressure to republish this important work.

Jack Common

Much of this day conference was taken up with family and friends' recollections

of these writers and detailed outlines of the books they wrote. These mostly

forgotten writers came alive again, and their problems as writers - trying to

find time to get the work done, trying to find publishers, arguing with each

other about form and style - seemed very contemporary.

Walter Allen is still alive, but only one of his six excellent novels is still

in print, All In A Lifetime. Walter Brierley, a Derbyshire miner who

corresponded with the Birmingham writers, published four novels, the finest of

which - and a classic account of the demoralisation of unemployment - The Means

Test Man is apparently going to be reprinted this year. John Hampson's most well

known book, Saturday Night at the Greyhound, like many of his other novels tried

to portray the predicament of a young homosexual man in the tough environment of

a mining village: this also apparently is to be reprinted, and is highly

recommended, not least for the author's courage in writing so personally about

such matters, in those highly censorious days.

It is to be hoped that in other towns contemporary working class writers,

together with local historians and teachers, will search out of the work of

earlier writers and make this known again. The firmer the foundations we build

on, the stronger our movement will be-.

Ken Worpole used to work at Centreprise in Hackney and has been involved in

publishing a lot of working class history and autobiography. He is treasurer of

the Federation of Worker Writers.

NEW WRITING

Unlike certain members of the literary establishment who believe that 'there are

too many writers and not enough readers,' worker writers have always stressed

the importance of encouraging more people to write. The short pieces on this

page are an attempt to represent this part of the movement. We hope that 'New

Writers' will be a regular feature of future VOICES. The writers here are all

members of Gatehouse's women's writers group.

PERSECUTED WOMAN

Doreen Ravenscroft

After a heated discussion with a friend of mine about woman's role in society, I

put my pen to paper and produced this short piece, and may I say I hope it will

provoke plenty of discussion:

Half of you deserve your lot, afraid things won't go your way, wanting all or

nothing, afraid to think in case he punishes you, in bed or out. Tread carefully

and smoulder until you are about to pop. Can't open up my feelings, I will be

classed as wicked but I feel them just the same. You were born free and have

your life distorted by different experiences until you end up some sort of

concoction they name Woman. Why let it happen? Do we need a new system? Must

woman prostitute herself in marriage to lead a worthwhile life? Hurry up Brave

New World!

SPRING

Josie Anderson

Spring is so delightful it must appeal

like a new born baby

so pure and clean and fresh

as they both unfurl their precious buds

to an audience eager to admire

effort rekindled

as you see the miracle yet again

NATIONAL SERVICE

Debbie Leigh

Born in a city tower block,

Alkatraz without the rock,

Sent to overcrowded schools,

Beaten up if you break the rules.

And our mothers sit and cry,

Because they know we're gonna die,

Beat the bulge with slimming meals,

Go to the seaside in stolen wheels.

You better watch out for the 'Boys in Blue',

You never know who's watching you,

Solicitors dressed in pinstriped suits,

Want us to wear marching boots.

This could be the story of anyone,

Just like daughter, just like son,

How about the 'Land of Hope & Glory',

Was it just a fairy story?

READING &WRITING PROBLEMS

Leah Hood

I would just like to say to people if anybody should have problems with their

reading and writing and feel they would like to write an article, but they are

worrying about their spelling, I feel they should not worry about their spelling

but put their ideas down on paper. With doing this it could help people in the

group to start getting their ideas down on paper and then talk to their teacher

about spelling problems.

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE

How 11 people survived as adult non-readers in a modern society that doesn't

accept or tolerate not being able to read and write. The book encourages an

awareness of reading and writing as a separate skill, _where some people can and

some can't with no shame attached to it.

£1.20. The 'Gatehouse Project, St. Lukes, Sawley Road, Miles Platting,

Manchester M10.

LONDON VOICES

London Voices was formed after a meeting called in Marx House, London, in

1974. Its main aim was to promote VOICES in London and the South.

It was not until 1979 that we became a poetry workshop in our own right. Meeting

monthly we gradually increased our skill in analysing, helping each other, and

passing judgement. The improvement has happened amongst a group of people from

very different backgrounds (engine driver, printer, social worker, housewife,

secretary, building worker, retired and unemployed persons to mention a few that

have come to the group). Nearly all are self-educated, and we are trying to

produce work which is accurate and truthful, reflecting the world as we see it.

Much of the work points to considerable political insight between the lines at

least, since the outright political poem is the hardest one to write, and those

who are brave enough to try, get the stiffest criticism.

The group has always been about equal numbers men and women, and the so-called

personal poems often written by women (and men on occasion) are particularly

valued. We publish them in a bi-monthly Broadsheet, and we are hoping to print

an anthology we have compiled.

The group now receives small sponsorship from the Co-op, who also helps produce

the Broadsheet. In exchange we read our work at Co-op Guilds, peace meetings

etc., as well as at CND meetings, cultural festivals, socials. We meet in the

Crown Tavern, Clerkenwell Green, or the Metropolitan Pub, Farringdon Rd., last

Friday in the month.

THERE'S A FOG OVER

LIVERPOOL

Pat O’Gorman

There's a fog hangs over Liverpool

The fog of C.S. gas

There's a plastic bullet waiting

to go through your head lass

My ring upon your finger

Is shining burnished gold

Love me now or never lass

We never may grow old

My brother served in Belfast

When they shot the Paddies down

I never thought the bullets

And the gas would hit our town

I never thought that Liverpool

Would see a barricade

And the C.S. gas come choking us

For petrol bombs we'd made

I thought the British copper

would protect me with his life

I never thought a bullet

Might come and kill my wife

I don't know much of politics

I didn't learn in school

But my eyes and ears are teaching me

That there's one golden rule

The politicians told the cops

To follow R.U.C.

And now the gas and bullets

Are turned on you and me

The workers always get it

Be they black or be they white

But they're rioters or terrorists

If they have the cheek to fight

My brother spoke of "terrorists"

When they shot the Paddies down

But now the bloody terrorists

Have come to Toxteth town

And they don't wear masks or berets

And their name's not I.R.A.

They're protecting Law and Order

In the good old British way.

LATE DAWNING

Rita Brewer

She sails her craft single-handed,

Outward-bound, no harbour in view,

Not chartered, the course of this voyage,

She had waited too long to make plans.

Looking back on the years left behind her,

She remembers her hopes slowly dying,

Her tenderness unshared, unanswered,

Submerging her essence, her soul.

Calming the wake of his anger,

soothing, placating, explaining,

Nights spent in dreamless exhaustion,

What use did her dreams have for him?

So long alone in the shadows,

The morning light dazzles her eyes,

Yet she welcomes the pain, and she savours

the chill autumn wind on her skin.

For these the signs of awakening,

Chrysaliding, rebirth as a person,

And her courage in facing the future,

Still the tremor of fear in her heart.

FOOL

Rosalin Howell

All alone at my sink

Pots and pans don't need my brain

I slowly remember all the hurt you've done me

Now my baby feels it too

that alone is unforgivable and where are you now

still working? I'm the last to know

can't stop thinking about the telephone call that Sunday

Still after all, they say it's only natural

Once bitten, never forgotten

Where is he, the husband, the father,

she needs you The son can't care anymore

too many - not this time luv, I'm playing darts –

Well, won't ask anymore

But the daughter - the bugger - the full of love - full of life

Still wants, still needs.

All alone at my sink

My tummy feels odd, like first time at a job,

like waiting outside the headmaster's room

Now my throat has a lump

Hurt me all you like, I yell inside

I've broad shoulders, I can cope - what lies –

Don't dare hurt my blonde baby girl

I love them both, I'm here when they need me

But him, where's he? where ever? when ever?

Oh man you are a fool to yourself.

TO JAPAN

Bill Eburn

'To Japan' is Chapter 11 of Bill's account of his experiences as a prisoner of

war.

(August - September 1944)

Manila again

Already I could see myself stretched out on the deck reading "Anne of Green

Gables" which I had thoughtfully omitted to return to the camp library. I hadn't

volunteered but the journey would make a welcome break.

We boarded a truck to Manila where we stayed up all night drawing our kit,

including a coconut pith helmet. We made a brave show as we marched over the

Pasig River to the harbour. I recognised one or two Filipinos, but none

recognised me. They looked at us in sorrow.

We lined up on the quay and in the distance could see a medium-sized ship, the

"Something-or-other Maru", and the front of our line going over the gangway. We

moved at a rapid pace but it seemed there would inevitably be a delay whilst the

ship cast off and another took its place. But the line kept moving. There was no

other ship.

All aboard

Rough hands received us. Everything was taken from us, except our mess kits,

shorts and singlets, and flung down into the lower hold. Some of us were pushed

into meshed cages in which all we could do was to lie down. "Who's that bastard

pissing on me?" enquired my neighbour, but it was only perspiration from the

chap overhead.

Chow time came and a flurry of flying figures, some getting more than one

ration, some none at all. In our cages we got nothing. It was difficult to know

what was happening. "Feel the man next to you and see if he's still breathing"

yelled my favourite M.O. above the tumult, although how we could do that I

wouldn't know.

I thought of the "Altmark", known to the British and American public as "The

Hell Ship". Conveying British POWs to Germany she was seized by the Royal Navy

who boarded her with drawn cutlasses. Much was made of the prisoners' privations

for in those early days of the war British propaganda was aimed at bringing

American into the war.

What cinema audiences saw of course was a reconstruction, but even from that it

was evident that the lads were seated in comfort, smoking and playing cards. I

wondered what the scribes back home would have made of this little lot.

Fore and aft

The next morning the Nips graciously allowed 600 of us to go forward, leaving

900 aft. Welcome as this was it still wasn't first class travel. By day there

was a constant stream waiting to use the can, so there was more room. But at

night it was difficult to find a place to park. You sat on the steel deck, your

legs straddling the man's in front, the man's behind straddling yours - like

negro slaves, except that we weren't chained. Sleep was no hardship. Slipping in

between two sleepers you wouldn't know, except for a muffled oath, they were

still alive. Once I had a bright idea. There was a vacant place beside the can

and I was able to lie flat out. It started to rain, warm at first as one might

expect, but getting warmer. Some poor fellow, half asleep, had missed the can.

Hit the deck

Three or four times a day this receptacle was hoisted aloft and the contents

emptied overboard. One day the string broke:

On the way to Japan

most of our time

was spent round the can

which, as required,

was hauled aloft

and emptied overboard.

On a sad day

the string gave way

allowing the contents

to descend on

the assembled company.

But we couldn't

complain all

the way to Japan,

and soon were lying

in our own despite

as to the manner born.

Sick bay

I had another bright idea. A flesh wound wouldn't heal and I reported sick. As

it grew dark the medic drew attention to the chalk line that marked the limits

of the sick bay. "Now don't forget", he said to those outside the charmed

circle, "We stay on our side of the line and you stay on yours." So once again I

stretched out thinking how lucky I was, and woke in a communal grave with more

and more bodies being flung on top of me. My good neighbours had stuck to their

side of the bargain until overtaken by sleep. I fought my way to the surface and

discharged myself as soon as it was light.

Loner

There was no-one to greet me for the other Limeys had been left aft and I was

one amongst 600 Americans. This wouldn't have deterred me for in the Philippines

where there were 8 of us and 8,000 of them, we had been made much of. But the

atmosphere wasn't conducive to making friends.

Every little group buzzed like an angry hive and these manifestations of

discontent echoing round the steel vault of the hold, sometimes reached menacing

proportions.

A wry ghost I wasn't conscious of being lonely; only of having no place to call

my own.

Therapy

Some of the first arrivals must have managed to hang on to various possessions

for the Chief Medical Officer, who was unfortunately the senior officer on

board, used to madden us by keeping up a constant stream of information about

items lost, and found. He may have thought this had some therapeutic value, like

the orchestras that continued to play as Nazi victims were led to the gas

chambers. If his object was to encourage us to give vent to our natural feelings

some of the answers he was receiving as to the disposal of these items suggested

he was only too successful; but the temperature required to be lowered, not

raised. Fortunately there were amongst us two characters who were competent to

do this.

The first was a joker who had managed to sling a hammock and spent his days

reading "The sun is my undoing". Either he sympathised with us or our brawling

made it difficult for him to concentrate; at any rate he offered to read to us,

and no-one could have had a more appreciative audience. "Anne of Green Gables"

where are you now? Down in the bilge with my precious letters and a pair of

boots anyone could be proud of.

The second character was the Padre (R.C.) who was able to command silence by

telling us what we wanted to hear. "Hail Mary, Full of grace..." he would begin,

and silence would fall like the setting sun. "You boys are sick... not

physically but mentally sick.... you'll need a course of rehabilitation when

this is over." This was re-assuring. Nothing was said about the US planes and

subs that were attacking shipping. We had heard gunfire and seen flames

spiralling from what we could only assume was a ship in our convoy. If we were

hit there could be no scaling the sheer walls of the hold. We would be trampled

underfoot, and the chances were the Nips would turn their guns on us.

Not a drop

"Who's drunk my water and pissed in the bottle?" enquires one fellow of his

mates, emptying the contents over them. Figures detach themselves from the main

body, and blows are exchanged amidst boos and cheers, until everyone sinks into

his former lassitude.

The Nips weren't enjoying this any more than we were, and after a couple of

warnings they cut off our water. For the first time since captivity hunger no

longer bothered us.

Fukuoka

Women come aboard to clear the lower holds. Our cherished possessions have

disappeared but our boots have been salvaged. Each man is issued with a pair

regardless of size or whether they be left or right, and we step ashore with

them dangling round our necks.

Some of us are taken to a hall where I for one, pillowed on my new-found boots,

sleep soundly. I see water spurting from a rock, cascading down into an

ever-growing stream, and wake to hear one of our chaps asking the guard to fetch

some; which he does, and is slapped by the sergeant for his pains.

Welcome to Japan!

A WEDDING IN THE IRISH

REPUBLIC

Evyn Rice

On the slipped lawn she stands, with careful spreading

Of her full-skirted gown, the veil of lace

Only half-hides the red-gold hair soft-falling

And leaves revealed the young lines of her face

He is lean-limbed, in well-cut light grey suiting

The dark eyes of the Celt, a jutting jaw,

Probably from Blackrock's quiet Dublin suburb

Looking as if he'd never roused the Law

He takes her hand and points to where, half-smiling,

The camera-man waits to record the day

Flutter of girls flower-wreathed and click of shutter

Captures Time's moment against Dalkey Bay

Guests gravitate towards the hotel, laughing,

Or lean on the sea wall to watch the tower

Of Dalkey Island, bride and groom still linger

Eye to eye holding back life's heightened hour

What are they thinking, poised among the roses?

She, Juliet-like, of night's surrendering breath?

Does she remember that North of the Border,

Nuptials are sealed with shots, smashed limbs and death?

And he, on fire tonight to prove his manhood

Feasting on love, sweet union of the flesh –

Will he remember those young hunger-strikers

Wasting their lives away inside Long Kesh?

FALLING OUT OF LOVE

Martin Jenkins

Falling out of love's like walking through showers

when the rainstorm's over, but you're not so sure,

and every drop of rain, you're running for cover,

soaked through already, so why should you care,

but anyway you dodge under the first tree

and watch the water trickle off the branches, gleaming

in a bright light from somewhere, and look up and see

the sunlight on the next hill, but still can't believe it.

LETTERS

Dear Voices,

Kathleen Horseman's review of NOT EXPECTING MIRACLES by Alice Linton was

thoughtful and interesting. However, what she had to say about introductions did

put my back up. Maybe that's only because I co-wrote the introduction with Jean Milloy, but I don't think so.

Kathleen wants Alice's book to make its own statement: I would say that Alice

Linton’s book, like all Federation writing, is not just its own statement.

Between Alice writing down her life story and the publication of it as a book

there was a whole wealth of work - not just work by Alice, Betsy, Jean and

myself - and others - in making that particular book, but a whole tradition of

creating a space, the encouragement and the achievement of working class

writing. For me, part of the importance of the Federation and the working class

writing it promotes, is the way it has brought producing a book into the range

of things that anyone can do. And I firmly believe that part of that process of

making writing and publishing more accessible to those of us who grew up

thinking it wasn't for the likes of us is to write an introduction that sets out

who did what, how long it took, and who the people are who helped. If we don't

have introductions then I think we run the risk of having our books just appear,

in much the same way anyone else's does and we lose that valuable exchange of

skill and information. We are different from the literary and the commercial

publishers and I think our introductions don't just follow a set formula, as

Kathleen complained, but are a very important way of showing just how we differ.

At the AGM I bought and read Peter Kearney's Glasgow From People's Publications,

it is a great collection of writing but has no introduction, not even a few

lines on the back cover, not even captions to the photographs. The book made its

own statement in so far as the poems were enjoyable and good to read and the

prose writing was informative too. But knowing nothing of who wrote them, or

how, or why, leaves me feeling something very important had been missed out.

Best wishes, Rebecca O'Rourke

Dear Voices,

I was glad to see

Phil Boyd's article in Voices 28. I have felt for some time

that the question of the quality of working class writing was being fudged and

it is good that it is being aired.

As a writer I see myself as a craftsman (with apologies for the sexist term). I

am at one with that mythical (perhaps) Rolls Royce worker who said that he

didn't work to a tolerance, 'it's either right or it's junk.' I don't think any

real worker finds difficulty in the idea that if a job, or a poem, is worth

doing, it's worth doing well.

Doing it well, in this context, means communicating, getting over the facts and

the feel of what you're writing about. In that sense Mickey Spillane is a good

writer: his style is dead right for the sexist, sadistic rubbish that is his

content. I loathe his matter, but his manner never bores me - and the second

half of that equation is the mark of a good writer.

I liked Voices 28. It was all good writing - I speak as a graduate (from a

working class family, I hasten to add) - and there was nothing in it not

immediately accessible to a working class family - I speak as a social worker

who has to communicate with them daily.

Can I now take up Wendy Whitfield's letter and suggest that Voices can enjoy a

useful relationship with the FWWCP and its member groups? If the job of the

groups is firstly to get ordinary working class people writing (never mind the

quality, feel the reality), it is secondly to help them, once started, to learn

to write well. What Voices should, in my view, be publishing is the best of the

member groups, the people who have learned. We should be able to say to new

writers, 'Joe Bloggs started just like you - and now he gets published in

Voices.' (Sorry - I'm being sexist again.)

Elitist? I'm sure it is - and it's elitist to prefer a piece of furniture made

by an expert worker to one made by an apprentice; but the expert was an

apprentice once, and we do our members no favours by helping them not to

complete their apprenticeship.

Yours fraternally, Martin F. Jenkins

Dear Voices,

Had a day-trip to London - and met up with your lovely magazine - after a short

period receiving it regularly in Norwich - so straight away - here

is my subscription.

Please do not fold and keep it up with lovely poems, short stories etc. As a

working class woman I can relate to it all - love it. Keep in touch.

Jeannette xx

A LETTER FROM MRS MAKANT

Paul Salveson

"It's either Mister Makant, or Driver

Makant t' thee" - the entire signing-on point, crowded with guards and locomen

on a busy Monday morning, went silent. The young management trainee immediately

wished he'd picked on someone else to exercise his new-found authority. Ezra

Makant was the crustiest of the old-hand drivers at Blackburn and the management

gave him a wide berth. "And if tha wants me to move that engine, it'd help to

say 'please'."

Apart from inbred awkwardness and sheer cunning - shared by many of the old

hands - Ezra had one special characteristic: obsessional inquisitiveness. It

probably began with the great interest many old railwaymen took in the Sunday

List, and seeing who was working their rest day. Fights had been known to break

out when one man suspected another of doing him out of a Sunday. The roster

clerks were old and wise enough to make sure Ezra got his Sundays in, so he

gradually broadened his interests to cover the doings of everyone at the depot -

as a sort of pastime. He would normally be found sat in the messroom, just by

the door. Casually perusing any paper he could find lying around, enveloped in a

haze of cigarette smoke - he looked harmless enough. The door would open, and

Ezra with leopard like cunning would spring the trap. "Whod art' doin?" was the

usual opening, and after that - if the victim showed willing - he just piled in.

"What time art’ on?" "Wheer's tha bin?" "Who wi?" until the poor bloke was

crying for mercy. Some of the secondmen ended up believing in reincarnation -

Ezra could only have been a throwback from the Spanish Inquisition.

To look at him, you'd say he'd had a hard life. His face was striking. Thin and

drawn, heavily lined and set off by sparse wiry hair. When he spoke the effort

seemed Herculean. His eyes would almost close as he pulled his face into a

grimace. His dress was fully in keeping with his looks. Winter or summer it was

the same railway overcoat - at least three sizes too big, acting as a sort of

bell tent for his meagre frame. He swore by the old 'company' overcoats - the

pre-1923 Lancashire and Yorkshire ones, nothing so modern as LMS! Behind his

locker was a stack of unopened boxes - containing his two-yearly issue of coats.

His boots were a similar vintage to the coat, though he made the occasional

concession to the leather trade by having them re-soled. Tradition has it that

the old railwaymen used to take great pride in having their boots highly

polished. If that is so, it was one tradition which passed Ezra by. The oil and

grime which held his pair together, combined with the coat and Ezra himself -

all made for a moving steam age relic. (Though many of the supervisors at the

depot came to regard him as a stationary exhibit!).

Don't get the impression Ezra lacked human warmth. He loved a joke, though it

was usually at someone else's expense. A favourite was to torment guards by

hooking the engine off from the rest of the train -after the guard had laboured

long and hard to get the train ready. When he got the 'tip' from the brake van,

Ezra would innocently set off, minus wagons and brake. When the guard came

panting down to the engine, Ezra would lean out and enquire "Hast fergeet t'hook

on cock?"

I'd had my fair share of Ezra's 'jokes', but when I worked with him on a long

distance job - Carlisle - a different side of him emerged. The train was

fully-braked so the guard's van was not necessary. I was riding in the loco cab

with Ezra, and after the initial enquiries about "my doings" the conversation

moved to wider things. His knowledge of his native East Lancashire was

encyclopaedic. Anecdotes about old Burnley characters, the Pendle Witches,

Chartist riots all flowed from him. With a bit of prompting from me, he began to

open up about his own life (I thought this justified because he made the most

intimate enquiries about other people's!) He'd started as a cleaner at the

small Colne L & Y ('Gown Lanky') shed when he was fourteen. When he reached

twenty he moved to Rose Grove - a few miles down the line - to get a fireman's

job. Then came the big move. It was wartime and the company was short of firemen

on the Midland at Derby. He signed on at the shed on Thursday morning and the

foreman handed him a letter:

Fireman E. Makant Rose Grove

Transfer Arrangements

Arrange to report at Derby (Midland Shed) 9:00 aw Monday 6.2.41 –

F. Hardcastle

District Loco Superintendent

Four days to get packed, move, get lodgings - and Ezra was not unusual in his

experience. Some of his mates got sent further south to the big London sheds.

After the initial shock, he felt he could have done worse. At least it was main

line work - heavy St. Pancras expresses with compounds and the newer '5X' 3

cylinder jobs. The most he'd got at Rose Grove was a slog over the Pennines with

a coal-hungry 'sea pig' or the occasional wakes special to Blackpool.

He'd met his future wife on the platform at Leicester - she was trying to get

back home to Derby, and as Ezra was going back 'on the cushions' after a twelve

hour stint on the shovel, they shared a compartment. A month later, they

'geet wed'. After the war ended a vacancy came up at Accrington. It

was near home, and Iris had grown to like East Lancashire on their trips up

there to see his parents. So they both agreed on the move, and Ezra got another

summary command this time more welcome - to report at Accrington for duty.

By 1960 the shed changed over completely to diesel. At a time when some steam

sheds were closing, everyone saw it as a good sign. Ezra was no sentimentalist

about steam and he took to the new diesels. Then the branches which the diesels

worked started falling under the Beeching Axe. The Bacup branch went, then the

Baxenden line, the Padiham loop, Skipton. There was less and less work for

Accrington's diesel fleet, and soon the rumours started to fly. The shed's worst

fears were soon confirmed. Newton Heath, the big Manchester shed, was to take

over maintenance and stabling of all the diesel units. Accrington would close

and redundant staff would be accommodated at Rose Grove and Lower Darwen.

For Ezra it was back to Rose Grove, and on some days at least, back to steam.

Four years later steam was drawing its last breath on BR and Rose Grove was the

final depot to close. August 1968 saw the curtain fall and even Ezra felt a

twinge of regret. For a while the drivers and guards signed on at the station

but everyone knew "The Grove" was finished. The yards - once the busiest in the

Lancashire - gradually grew quieter. The night turn pilot was knocked off. Some

of the sidings were lifted. By 1972 the lot went, and Ezra found himself, with

the remaining ex-Rose Grove men - travelling each day to Blackburn.

By this time, Lower Darwen, the old steam depot at Blackburn, had closed as

well. The 'Darreners' signed on at the station and it was here the Rose Grovers

went. In the face of common adversity - redundancy -the forced marriage of the

two old rival sheds actually worked. No-one liked the extra travel from Burnley,

Nelson and Colne but at least the company laid; on a staff train during the

night for the displaced men; and they got travelling time.

The move to Blackburn gave Ezra and the other 'Grove men' the chance to learn

the Carlisle road. Not the easy way over Shap, but the Long Drag from Settle.

Ten miles of hard unrelenting climbing up to the wilds of Blea Moor. Even the

diesels sometime found it too much.

After my first trip with him, the next one over that road was to be the last -

for both of us. I was moving on to a different grade, and Ezra was retiring. We

signed on at 6am - a beautiful early Autumn morning. Our train was witing - 1000

tons of rock salt for Scottish factories. The run through the Ribble Valley was

a delight, with Pendle Hill watching our progress as the Class 40 loco got stuck

into the sharp climb from Chatburn to Rimington. We were in 'witch' country now,

and Ezra had a few entertaining stories of witches and 'boggarts' - (Lancashire

ghosts). After Hellifield the country becomes more rugged as the line bites into

the limestone hills. This is the start of the Long Drag. Upper Ribblesdale is

not the place to go for fine weather in October - but today it was gorgeous. As

we settled down to a steady 20 mph I pulled the camera out of my guard's bag and

took a few shots of Whernside, Penyghent and Wild Boar Fell. I also managed to

get a couple of sly shots of Ezra - much to his consternation!

We got relief at Carlisle by a Scottish crew - 'Caley men’ to Ezra, (though the

Caledonian Railway went out in 1923!). That day we were 'home passenger' via

Preston. I filled the brew can up in the mess room and came out just as our

train pulled in. Settling down with a huge pot of tea Ezra was in a reflective

mood as the electric whisked us up the Eden Valley. I was going on to new things

- his working life was coming to an end. "Aw tell thi aw'll bi glad to be out o'

this lot. Railroad as aw knew it's finished. Aw've bin pissed abeawt from pillar

to post these forty year. Management today couldn't run a bloody chip shop -

neer mind a railroad. Like that daft bugger of a trainee. Tha cornt run this lot

wi a university degree - it teks skill and experience - years of it. Leek a lot

o' the' guards today - can't even use 't' pole (shunting pole for coupling

wagons) - but aw blame this management. Tha can't tek a man off the street and

turn him into a guard just like that. In th'owd days they served their time as

porter and shunter. But not today. Oh no! Bloody railways - aw hope aw never

sets eyes on a train agen when aw finish.'"

Ezra's intentions were to get down to writing a book on his home town of Nelson

- about the Luddites and Chartists - the handloom weavers and the early factory

masters. He'd also do that decorating he'd been promising Iris.

We signed off at Blackburn and Ezra, slightly embarrassed, took my hand. "Good

luck cock" - and he was away over the track to get his train home. The next time

I saw him was at Preston. I was returning from the north, and as we drew in I

caught sight of Ezra across the platforms. A driver was revving up a diesel unit

trying unsuccessfully to create vacuum pressure to release the brakes I suppose.

Ezra was eyeing him with a look of disdain. The roar of the engines made it

impossible to shout over to him and the next minute my train pulled out -

leaving Ezra stood there, for once minus overcoat. The fag was still in the

corner of his mouth.

Two months later, I received a letter postmarked "Burnley". It was from Mrs

Makant:

Dear Mr. Salveson,

I am sorry to bother you, but I am writing about my late husband, Ezra. You may

have heard he passed away last month after a sudden heart attack. I remember him

telling me you took some pictures of him on the railway and I would be very

grateful if you could send me some copies for which I will of course pay you.

Ezra never let me take any pictures of him and it would be a little something to

remember him by.

Yours faithfully Iris Makant (mrs)

A Letter From Mrs. Makant is an account of a real life incident. Paul

Salveson is an ex-railwayman and a keen photographer.

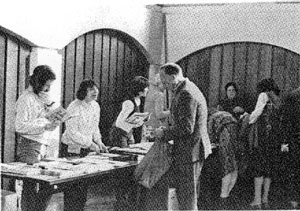

THE FEDERATION OF WORKER

WRITERS AGM

For some of us the Federation AGM held this April at Nottingham University was a

chance to renew old friendships and continue discussions that have been going on

for years: for others, put off maybe in previous years by the thought of

anything so formal as an AGM, it was a new experience. The business in fact took

up only a fraction of the two days, the rest being given over to workshops,

bookselling, and socialising. The aim of these seven pages is to give an account

of a few of the workshops and the ideas produced by them which should form part

of the agenda for the Federation over the coming year, but mainly to concentrate

upon some of the writing that was performed and read out, and hopefully explain

why 120 hard-up people should take the trouble of converging on Nottingham and

leave determined to be back in twelve months time.

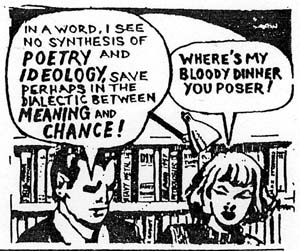

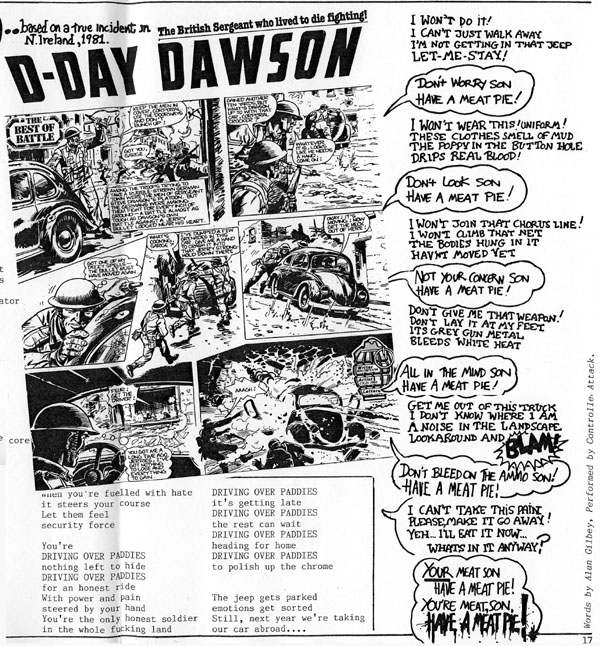

Things were set in motion on Friday evening with a performance by Controlled

Attack, the East End theatre/satire/poetry/comedy group. (Eyes right for a

couple of things they performed). Saturday morning was bookstalls on which were

displayed around a hundred worker writer titles, and writers workshops providing

an opportunity to get to know each other and our work. The weather being kind

for once, many of us were able to sit outside on the grass, lulling ourselves

into a false sense of relaxation before an afternoon given over to discussion

and business.

Apart from workshops reported elsewhere, there were ones on performance in which

people pooled their experiences (good and awful), discussing the best way to

make the words leap off the page to seize the audience by the throat; on working

class history; and on poetry as an expression of working class life.

For many of us the highpoint of the weekend was the social on Saturday night.

During the mammoth three hour reading all those phrases about the richness and

variety of working class writing with which we are familiar suddenly rang even

truer, with poems, stories and sketches from all over the country.

Sunday morning saw hangovers and another round of workshops including ones on

VOICES and on gay writers within the Federation, the latter obviously making

some people unhappy. (Perhaps further discussion in the pages of VOICES is

called for.) And so to the final session designed to draw different threads

together and then to the long road home......

DRIVING OVER PADDIES

Hold that steering wheel

in brown gloves

Young peacekeeper

who no side loves

From your jeep

what do you see?

A thousand shades

of bigotry?

Just doing your job

on a dangerous ride

In the name of God

shot by both sides

Caught in the middle

patrolling the peace

(checking the mirror

ignition release)

But that's not true

be honest and admit

That deep inside

there's a tiny little bit

That's bitter and festers

and grows and hates

That weights the accelerator

releases the brakes

That unsheaths speed

hard and true

You're running at

upon, into.

You're

DRIVING OVER PADDIES

for a smoother ride

DRIVING OVER PADDIES

no need to hide

Motives and emotions

let them push up from the core'

DRIVING OVER PADDIES

Pedestrian war

Up on the pavement

the pretence is gone

Red on the windscreen

wipers on

Smiles on your faces

bodies on the tar

Skittle of a nation

bullet of a car

Screaming, running

out of breath

It's clunk-click

every death

It's "Can't keep running

got to stop."

They're under your wheels

you're out on top

when you're fuelled with hate

it steers your course

Let them feel security force

You're

DRIVING OVER PADDIES

nothing left to hide

DRIVING OVER PADDIES

for an honest ride

With power and pain

steered by your hand

You're the only honest soldier

in the whole fucking land

DRIVING OVER PADDIES

it's getting late

DRIVING OVER PADDIES

the rest can wait

DRIVING OVER PADDIES

heading for home

DRIVING OVER PADDIES

to polish up the chrome

The jeep gets parked

emotions get sorted

Still, next year we're taking

our car abroad....

THE BOURGOISIE

Wendy Richmond ((Heeley)

scruffy clothes

a necessity

sexless dungarees

the uniform

you can tell them from a long way off

the battered vans

grimy windows

milk bottle gardens

out of date posters

and you can hear them when they begin to speak

looking sympathetically

as their nice smiles pat you on the head

you can see the books on the shelves

holding

the latest rave

of the latest ism

and you can tell them by the serious look

which overcasts the face

taling about their lives

the importance of

the reason for

you should and must and could

you can see the guilt surrounding them

needing to escape

degrees and mortgages

and so many responsibilities

and the worry about doing it all the right way

but space and time don't always allow

you can tell them by the groups they join

of houses shared

children, money, lovers, and bread

outside

open air

light a cigarette

and swear

you can tell them from a long way off___

RACIST ATTACKS

The FWWCP asks the Arts Council to urge the Home Secretary to pay greater

attention to the increasing attacks on bookshops. There can be no serious

literary and political culture if bookshops are subject to harassment from

racists and neo-fascists. Since the promotion of culture is the main objective

of ACGB, these attacks must be of direct concern to it, and it cannot remain

aloof. (From a statement agreed by the AGM)

SELLING OUT

As small, usually local publishers, Federation members have an uphill battle

selling to a national readership. The workshop on marketing went some way to

defining the problems and coming up with a few solutions. Having discussed the

need 'to project ourselves as having a collective and separate identity rather

than attempting to integrate ourselves into the mainstream of Literature', there

were two main proposals: to coordinate the selling of all our books at meetings

and conferences; and to organise reviews and publicity for all new publications.

This would mean more reviews in VOICES and providing reviews for the press. The

workshop also went into questions of pricing, selling to specific markets such

as schools and libraries, 'product image', and stressed the constant need to

develop personal sales.

WOMEN WRITERS

In past years at the AGM, we've argued the place of women-only groups in a

working class federation. This year, we came together to tackle the practical

problems of women writers. Whether we came from a mixed group, a women's group

or one of those that turns out mainly female by circumstance, all of us had

experience of a floating membership; a woman will arrive at a group eager to

take part, yet within weeks has drifted away with no explanation. The reasons

for this are fairly obvious. Under pressure from family demands, women don't

have the privacy, time or energy to keep up their writing.

Solutions aren't easy to find. Some of us felt that more links with adult

education would make a more comfortable framework for women, particularly if

writers' workshops could be based at centres where a range of other activities

were already going on. At the same time, we want to keep up the relaxed

atmosphere of most workshops, offering support and chat and the means to

self-confidence without forcing anyone to turn out "homework". Our groups are

about much more than simply getting a few poems on the page.

Ailsa Cox, Commonword

THE ORANGE

Sue May (Hackney)

An orange sat in the drawer of a desk

at the back

in the dark corner

where it had rolled and hid one day

when the man of the desk

went out to lunch

and threw his sandwiches away.

He forgot about the orange,

which soon made friends

with the paperclips

and the staplegun

and the compliments slips.

Day after day

in the dark

the orange sat tight

waiting to be

rolled by strong hands

and helped off with its skin

so eagerly that it would get ripped

and laugh at the tickling

and squirt in the eye of the beholder;

it sat hoping and wanting

to be

sucked and kissed by a searching tongue,

it was ready

to be

torn into quarters and shared out

between many tongues and teeth

as oranges often are.

It said to itself

'I've got the pip' and laughed

a bit sadly.

It got all lonesome and blue

and white

and looked like someone's tongue

when they're not well.

It thought it was going grey before its time

and its tears would have rolled down like rain

if only someone had squeezed it.

When the owner of the desk

moved to another job

he cleared his drawer out,

hoping to find his long lost

magnetic scrabble set;

his hand closed around the orange,

furry as a balled-up spider dyed white

'look at this Nige' he said,

and threw it away

JOB CENTRE

Beth Edge (Heeley)

This is not the Thirties.

The place is bright as lipstick

And well-groomed as the girl

In the swivel chair.

She dizzies round, just for the hell

But, always in control,

Ends firmly facing her typewriter.

Her fingers fit the keys precisely.

A staccato of neat white cards

Announces what's on offer.

I sidle over, neutrally.

There's nothing there!

Does the Job Library

House fact or fiction?

"Have you registered?"

The question takes me by surprise,

But she is keen to help

So I approach the desk.

She opens a drawer

In the filing-cabinet.

It slides out strong and smoothly.

I half expect to see

A label tied around a cold big toe,

But there are only cards

With names.

Now I'm in there.

At last I have a place.

That's me - a card in a drawer

Marked O to Z.

She shuts it with a satisfying click.

BURDEN ON THE STATE

Peter Carroll (Nottingham)

I was a member

I must confess

a high ranking officer

in the DHSS

but I was only obeying orders

we knew nothing of the distress

just rules and regulations of the DHSS.

What can just one man do

we were trying to make it a success,

it was just a clerical job like any other

with responsibilities yes

but it was all just names and figures

you get accustomed to it I guess

Of course we knew of some poor people

whose lives were in a mess

existing hand to mouth

constantly under stress,

pitiful some cases

I suppose they did impress,

but the rule was if you could

you had to give them less.

It wasn't real life you see

more a game of chess

I was going to expose it all

and tell my story to the press

but we were only obeying orders

at the DHSS

Why do they call me Rudolf Hess?

Since the AGM, Nottingham Writers' Workshop has applied to join the

Federation. Their book, From Egypt Road to Cairo Street, is due out

this autumn.

VIDEO

Worker writers have always been interested in more than the printed word. We

organise poetry readings. A number of us have written and performed plays and

sketches. Basement writers have just put out a cassette of Gladys McGee's poems.

In Nottingham a group of us discussed the use of video. Our starting point was

the experience some people had had using video with young children and with

teenagers. The workshop then developed some of these ideas and we talked about

using video to rehearse our public performances, and also the possibility of

groups making their own videos and thus reaching a wider audience. (Parts of the

AGM were being filmed. We look forward to being able to review the video!)

SCHOOL

F. Lydon (Tottenham)

I went to school,

Not because I wanted to,

I had to go,

Law of the land,

That's what I was always being told,

Rules were to be stuck to,

They were for your own good,

To help you become a better person,

Teachers were for teaching,

And students were to study,

I felt lonely and I wanted to leave,

But the rules wouldn't let me,

But when I did leave school

I felt lonelier and I wanted, to return.

PAPER BAG RAG

John Alien (THAP)

It was raining that day as I stood at the gates

of the hospital, smoking a fag.

My old man you see had just passed on

and they gave me this old paper bag.

He didn't leave me much you know

a quid or two, a tin of shag

A pair of his socks, an old silver watch

wrapped up in this old paper bag

Now I thought to myself, as I stood in the rain

that old man never did brag he'd had a hard life, now it's all

come to this wrapped up in an old paper bag

It makes a bloke think, when all's said and done

that life can be such a drag,

you can pick it all up and throw it away

wrapped up in an old paper bag.

WHERE IS THE SUN

Sally Flood (Basement)

Damp, clammy hands -

touch each corner of my mind.

Fill my eyes –

and make it hard to find.

The treasure that I seek

is hidden by the bleak

sheets of pouring rain.

Automatically -

I chase the dust, that I can see,

Fill the sink with soapy suds -

and last night's greasy plates.

Brush the skirting, and the stairs,

and feel the damp air mocking me.

Strip the bed, sweep the floor,

- dinner time is here once more.

Back to soapsuds and the plates

- dreamily thinking of my mates

back at work,

envying me,

my winter break!

THE FEDERATION AND THE FUTURE

The Federation's success is often expressed in terms of our growth from 8

member groups six years ago to the present thirty. This year we took the

opportunity to take a more careful look. Members of different groups explained

what the Federation meant for them. Some people pointed to practical things such

as promoting book sales and overcoming the isolation felt by individual groups,

while others saw the political importance of the Federation 'as the only

organisation that truly represents working class writers and demonstrates daily

the potential of working people.'

Arising out of the discussion was the feeling that while the Federation had come

to life during the weekend, we needed to do more throughout the year to involve

the membership. We wanted to see more events such as those organised by groups

in the South West enabling writers to meet either on a regional basis or

according to a common interest (eg working class history, women's writing). We

needed to involve more people in producing and writing for VOICES. And finally

we agreed to set up a fund produced by donating copies of our books to the

Federation, to pay members of one group to travel to readings organised by

another.

THE NEW EXECUTIVE

Eddie Barrett (Chairperson) (Scotland Road)

Ken Worpole (Treasurer) (Hackney)

Ian Bild (Secretary) (Bristol Broadsides)

Ailsa Cox (Assistant Sec.) (Commonword)

Jackie Abendstern (Commonword)

Sally Flood (Basement)

Alf Ironmonger (Commonword)

Jimmy McGovern (Scotland Road)

Rebecca O'Rourke (Centreprise)

Petrona White (Bristol Broadsides)

Chris Carson

LASTING IMPRESSIONS NOTTINGHAM '82

Marion Shaw (Commonword)

The dining room - large and airy. Long tables, full of food. Eating massive

breakfasts, fried egg and bacon, sausage and mushrooms. Silver jugs, the smell

of coffee. Ailsa's little boy, Tom. A baby girl.

The bar - adjoining the dining room. Cosy, but closed too early. The discussions

and workshops. The intensity but also the sincerity of the people. The talk

about "Voices" magazine.

The discussion on how workshops function - surprised to find some had no

premises, some sometimes had no written work, so discussed articles in the

paper. Other groups had to have written something before they were allowed to

join in with the group. One group had kept going for six months with just two

people. Whether to advertise or not.

The readings on Saturday night. All the different dialects. The chirpy Liverpool

girl, telling her story of a baby born in hospital ("Put that baby down").

The older woman reading her amusing story of Noah's wife finding a leak.

Joan, reading in her soft Welsh voice.

The A.G.M. The woman Chairman (or Chairwoman) trying to keep the meeting moving

on. The voting for delegates. The horse that didn't win.

A crooked spire at Chesterfield.

A van rushing through the Derbyshire countryside crammed with boxes and books,

twelve people and two babies. Speeding home.

SKYDODGE

Tom McLennan

Now the mugger on the street

For the sake of fifty pound

Will go before the beak

Most likely to go down

For the press is very savage

On crimes of that there kind

But do their headlines rant and rave

About robberies like mine

O no, not me,

I'm Freddy, fat Freddy

Honey maker

Heart breaker

And the sun shines out my arse.

Now the little clerk who sweats

A lifetime at the till

With amounts of cash he never gets

And knows he never will

When his hands grow sticky

And he decides to take a chance

You can bet your life real quickie

He'll be doing that jailhouse dance

But me, not me

I'm Freddy, fat Freddy

Money maker

Heart breaker

And the sun shines out my arse.

Now if you are one to disagree

The world's a crazy affair

Then explain, my friend,

How a man can be

A bankrupt millionaire

For I owe a good few ackers

I ripped them off good style

But they cheered me

as I kicked them in the nackers

I must have an honest smile

That's me alright, that's me

Honest fat Freddy

Money maker

Heart breaker

And the sun shines out my arse.

Now the lesson to be learnt

If you take advice from me

The crime's not being bent

It's a matter of quantity

Steal a pound or two when poor

You'll pay the usual price

But two or three million more

That's private enterprise

I'm Freddy, fat Freddy

Money maker

Heart breaker

And the sun shines out my arse.

Tom McLennan is a member of Liverpool 3 Writers

RUGBY

Geddes Thomson

I never did like rugby much,

Since that first desperate scrum

On the playing-fields of long ago.

Too much type-casting for me,

Too much of a premium on beef;

All that boys-together stuff

In the bath after the game,

The ritual pints of beer,

Those pathetic insecure

Woman-hating songs they roar

Like dirty-minded little boys.

I never did like rugby much

And today, when they ignore

The world for the sake of a game,

I like it even less.

Geddes Thomson teaches English in a Glasgow comprehensive

school.

JUST MY SIZE

John Walsh

He was digging a deep hole

but stopped to look at me

and jokingly to myself

I wondered where the body was

I don't like the way he keeps

looking at me.

John Walsh comes from Runcorn.

A FLORIDA FERNERY

Bleu Harrison

A cloud of dust billowed up around

the van as they came to a stop in front of a cluster of dilapidated white

clapboard houses. The three women looked around uncertainly, watching as a man

emerged from a large hothouse crammed with the glowing green growth of thousands

of ferns and approached, shouting back instructions over his shoulder to a

blonde, beefy-faced man dressed in blue denim overalls, from which his grossly

overindulged stomach threatened to escape.

Blue eyes darting enquiry from his weather-beaten face, he asked if he could

help them. They said that they had called in response to an advertisement for

workers the day before and the man they had spoken to had told them to come

right on down.

He nodded agreement.

"Yeah, we've got work," he said. "You can start right away if you

want...Where're you staying now..you need a place to live in while you're

working?"

The three women looked at each other enquiringly, then, "What kind of a place do

you have and for how much?" Maria asked non-committally.

The man launched into a monologue about a caravan just big enough for the three

of them, that he had just set up - only a couple of days before in face -

unless, that is, they wanted something bigger? His eyes questioned them.

"How much?" Amy persisted.

"Twenty-five for the smaller one...that includes water and electricity, but you

pay for the gas. If you want the bigger one it'll be a hundred and fifteen..."

His voiced trailed off as they shook their heads.

"It's a gas stove?" asked Rose.

"Yeah, that's right, honey. Well you wanna take a look at it girls?"

The women looked at each other, eyebrows raised in query. What did they have to

lose anyway? Right now they were in need of a job and a place to stay and, in

these parts, that seemed to be an elusive combination.

"Ah'll show you where it is," he said, "ah'm headed that way myself... ah'll

just ride along with you girls up there, if ah may."

Smiling as he spoke, he proceeded to climb into the passenger seat, where

Graycloud, their puppy, immediately clambered into his lap to his evident

discomfort, bracing herself against him as the van bounced over the ruts and

back onto the road.

They sped along the narrow road lined with ferneries and orange groves, he

struggling to restrain the dog as she lunged for the open window, ears flapping

in his eyes and saliva blowing back into his face from the breeze and, while he

cringed from the sharp digging of her nails into the fleshy part of his thigh,

he regaled them with excepts from his life story and tales of how he had

travelled the long road from his former executive position in a world-renowned

construction company in New Jersey to his present post as manager of a fernery,

which he had taken up on his retirement to Florida five years before.

"And ah'd rather take this job here, outside in the fresh air in the midst of

nature, than that other one, any time," he concluded as they pulled up in front

of another group of rundown wooden shacks where two paunchy white men were

loading ferns onto a pick-up truck.

Nodding a greeting to the two men, he turned back to the women. "See that house

there?" He pointed to a large building, originally white but with the paint now

peeling off in long strips. "That's one of the workers' houses - a whole bunch

of them young men sleep right in there." He walked on around the side of the

building, round to the back, where the shadowy forms of workers could be

discerned in the dim gloom of the fernery, stooped over the rows of green

fronds.

"And this here's the caravan that you'd be livin in."

He opened the door with a key and showed them inside - a pile of dirty dishes

sat in the grimy sink, a charred pot with the remains of an unappetising-looking

meal rested on the grease-bespattered top of the stove and a musty smell

permeated the air.

"Yeah, this is the caravan for three people. Twenty five dollars this one is.

Yer see - here's the

other bed, just folds down like this," he struggled to lower it, fumbling with

the catch and finally succeeding, "and then you can fold it up so that it's out

of yer way during the day. An1 that's the other bed..." he pointed to a skinny

sofa and the three women, who could barely find room to stand all at the same

time in the miniscule interior, nodded their recognition.

"And here's the refrigerator." Cockroaches and ants scurried for shelter,

abandoning the pile of dirt and mould in the bottom of it as he opened the door,

letting in the bright rays of sunlight. He shut it again hurriedly. "Of course,

it'll need a bit of a clean-up - one of the workers been living in here for a

bit."

Edging past them he opened another door. "And this is the bathroom -yer see it

has its own shower," he said. A strong smell of urine wafted out into the room

as he hastily closed the door.

"And this is the clothes-press," he brushed past Maria who quickly sidled into

the space that he had just vacated, staring into the narrow cupboard that now

stood exposed.

He looked at them expectantly, his tour of the caravan now completed, but their

faces betrayed no emotion so he quickly ushered them outside, pointing out the

other, larger caravan

a bare six feet away. "Would you like to see this other one," he asked,