|

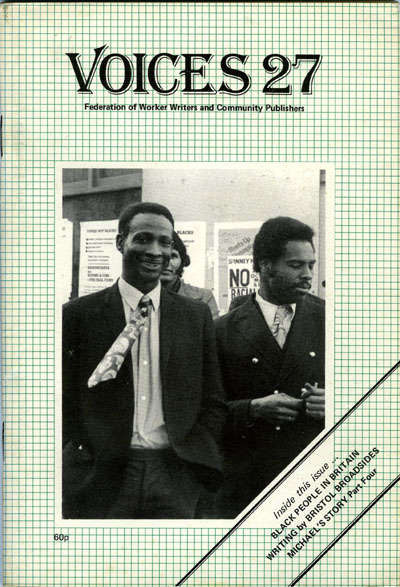

ISSUE 27

cover size 210 x 148 mm (A5)

CONTENTS

EDITORIAL

On being asked would I like to write the editorial for VOICES 27, I readily

admit I didn't feel over-confident. I realised I hadn't seen all the material

going into the magazine, but enough to tell me it would be interesting,

enjoyable and on the whole, widely representative of the worker writer movement.

The conclusion of Michael's Story is something many of us have been looking

forward to. There are some interesting women's pieces, and the Bristol worker

writers are well represented.

Women's writing is always a sore point with VOICES. Why? Because they never have

enough. I know there are excellent pieces out there, because I have seen and

read them. Working class women do produce good work. Is the fact that it is so

thin on the ground due to the pressures of this society, or is it that we lack

confidence in our own ability? I have to ask these questions in order to move a

little nearer the answers. The difficulty in maintaining balance in the content

of VOICES is increased by this ongoing problem: only women writers can relieve

it.

To change direction a little, I feel I should mention that in April the

Federation of Worker Writers and Community Publishers held their annual general

meeting at Nottingham University. It was a lovely feeling having representatives

of so many groups under one roof. Worker writers from as far apart as London,

Bristol, Newcastle Manchester and Liverpool, all with a common commitment to

writing and publishing were there.

During the weekend people attended a wide variety of workshops but one in

particular was of great interest. The subject matter was VOICES, standards and

criteria. One of the many questions asked was, "How does VOICES choose or reject

material?" The answer to that question is as follows. Work sent in to VOICES is

collected into a 'fairly' neat pile. The members of the editorial group read

through every piece individually, marking the work as it is read. It is then

passed on to the next editorial member until everyone has read, commented upon

and given a grading mark to the pieces. At a later date the whole editorial

group come together to discuss and select

material for the magazine. The self selecting pieces (those having an A rating

plus glowing comment) take up little time. Pieces in the middle range are more

difficult and sometimes require much discussion, even argument. The previously

mentioned problem always arises: shortage of women's work. A great effort is

made to maintain the balance required for a magazine like VOICES for instance

women /men, social/political, home/industry etc.

Coming back to the discussion on standards, criteria, we all have our own

opinions. This is a healthy state of affairs, the arguments go on.

I speak as a working class women writer and say, we must continue to question

the word 'standards', not because we are not working towards excellence, of

course we are!, but we should ask, whose standards?

If taken to extremes is there not a danger of these same 'standards' destroying

the very thing we have created? What have we created? The right to have our

culture validated. The right to use our own language to describe our own lives,

to kill the myth, colloquial is quaint. I believe we have to be careful in our

selection of the criteria and standards we adopt. What could happen? We could be

swamped by the sophisticated, killed by the glossy finish and lose the rough

edges to our words that portray the rough edges to our lives.

Finally, read VOICES 27, enjoy the rough edges, alongside the sophisticated:

there is room for both. If you think this editorial is unpolished, well, I

didn't promise you anything of 'great literary merit', you have to take me as

you find me, 'warts and all'. I wish you all peace.

Olive Rogers

(Liverpool 8)

(Olive is the part time literature development officer employed by the

Federation of Worker Writers and Community Publishers).

Amidst Smoke and Curses

Outside in the dusk three sheepdogs wait,

One sitting, one crouching, one lying by the gate.

Inside is beer, talk and cards.

An endless troop of feet to the yard.

The world through misty windows fades,

As pipes and fags colour in the air.

The beer resigns itself to fate.

Down the pints as fast as you dare.

Plotting caps nod to the floor,

Fidgeting fingers have heard it before.

Next to the largest glass of gin.

An old man stirs the fire and sings.

Insults fly across the bar,

Domino players bang and curse.

Time sweep on and sweep out care,

And by sweeping on make these boozers worse.

If you're sure the keeper is in,

Leave by the back-slip the chain

Down the fields to the river-side.

Lift the fish collect it by night.

The landlord calls, the night is done,

Leave-taking takes us friends wherever.

In hazy mind the words did run

Please preserve this pub forever.

Jonathan Hauxwell

(East Durham Writers Workshop)

The Pit's Closed

Pit head gear, black girders

Haloed by the Moon,

Pulley wheels still, bereft of their steel ropes,

Useless, waiting for the scrap-man's cutting flame.

At bank, where once the "chuck" of kepps banged home,

The hiss of rams and rumble of the tubs,

The banksman's bells and swish of rope upon the shoes;

Silence, save for the wind-blown dust.

The gleaming cylinders rusted now.

Where steam its power played,

The big end poised, to work no more,

The drum its life-work done,

That engine house where men lived out their lives;

Quiet as the tomb.

And down that shaft, where cages rushed,

Another world lies still,

Not even one echoing footstep

Where once boots clattered;

Back-shift out, night-shift in.

Those ways to Hell:-

Straight South, North drift, and East if lot decreed,

No sound except the drip of water seeping through the roof,

While Mother Earth relentlessly reclaims her own;

No girders now to hold her back.

Ron Oliver

(East Durham Writers Workshop)

Factory

These girders hold up my world,

shot through with stout rivets.

An architecture of purpose

and specific design.

like the brain of a mathematician.

Row upon row of geometrically constructed beams.

A giant Meccano set

painted black to hide the rust.

A spider's web of iron.

A symbol of stress and distress.

Thick black lines

painted on a canvas of industry and labour.

Kevin Cadwallender

(East Durham Writers Workshop)

If you can't manage the job

"Sorry Joe, your machine's broke down so you'll have to go on the

labouring gang for a couple of days."

"What?" asked Joe startled, hoping that he hadn't heard correctly but knowing

that he had.

Sid, the chargehand repeated the bad news.

"Er . . . well . . . what about the spare," Joe mumbled, "can't we use that?"

"No, that's knackered as well, and by the time they get it fixed it'll probably

be rusted bloody solid. But you'll be alright," Sid added, "It'll only be for a

couple of days, then I'll have you back on here."

Unable to think of anything else to say Joe stood there, looking at the broken

machine.

"We'll see you later," Sid said, giving Joe a friendly pat on the shoulder, "I'm

making a brew before the whistle goes."

Joe stood there alone staring at the machine. He felt sick. He'd worked in the

mechanised foundry for just over ten years now, and except for the first couple

of months, which he'd spent on the labouring gang, he'd worked on the core

plant. The job was boring, repetitive and unhealthy, but by mech. standards it

was a cushy number and Joe knew it. The jobs in the mech. varied from the bad to

the bloody awful, and on the labouring gang you could end up with any one of

them. It had been bad enough on the gang the first time; but now he was almost

sixty, and felt every day of it. Ten years on the core plant, breathing in the

fumes given off by the baking sand cores had made his already weak chest even

weaker. He'd lost count of the number of times his doctor had told him to leave

the job for the sake of his health. But where else could he get a job with as

good a wage, in fact where at his age could he get a job? Anyway, the work

itself was relatively light, it was only the fumes that bothered him. But. The

atmosphere on the core plant was like fresh air compared to that in other parts

of the mech. The very thought of some of the jobs scared him, he just didn't

think that he would be physically capable of doing them any more and he knew

what would happen then. The management here worked on the basis of the time

honoured principle: "If you can't manage the job get out." Still, it was only

for a couple of days ... he'd manage ... he'd have to.

There were only about five minutes left before the whistle and so Joe made his

way to the other end of the core plant to where the labourers gathered every

morning to be assigned to their various jobs. Six or seven of them were already

there, sitting or leaning on anything convenient. The whistle went as Joe

arrived; it was 7.45 a.m. Eight or nine others gradually arrived in twos and

threes to swell the size of the gang. They were mainly in their late teens or

early twenties, a few were older, but not as old as Joe. Some of the young ones

were laughing and fooling about reliving some of the funnier parts of their

weekend, but most were either chatting quietly with their neighbours or just

dozing, wishing they were still in bed. Joe was just about to begin inflicting

his problems on the young lad leaning next to him when Jimmy Walsh, the

chargehand over the labouring gang came around the corner.

"Everybody happy?" shouted Jimmy to nobody in particular, rubbing his hands and

smiling.

"Get stuffed," one of the dozers replied.

"Right then lets get on with it," Jimmy said, still rubbing his hands and

smiling, looking round to see who had turned in and who hadn't.

As usual on a Monday morning quite a few hadn't; still there were enough to fill

the essential jobs. "What are you doing here?" he asked when he noticed Joe.

"Well don't worry about it," he said when Joe had told him, "I'll see you're

alright."

Joe was relieved, maybe things wouldn't turn out so bad after all. Meanwhile

Jimmy sent the gang to work, to casting, dressing, machine moulding; and some to

cleaning up in the black, dust-filled tunnels called the spillage that ran

underneath the foundry. In fact they were dispersed throughout the whole

mechanised foundry system.

"Well then Joe," Jimmy asked, still smiling, though his hands were now in his

pockets, "how do you fancy a day on the sand-wagon?"

A day on the sand-wagon meant that Joe would be working outside on what promised

to be a pleasant summers day. He would have to spade a train-wagon-load of sand

onto a conveyer belt which carried the sand to the core plant inside the

factory. And, although at first sight it might seem to be a lot, after thinking

it over for a split second Joe nodded, smiling back at Jimmy.

"Just the thing," he replied. Knowing that if he worked easily but steadily he

could have the wagon empty with at least an hour to spare before finishing time

at 4.30. Also, with a chest like his, a day working in the fresh air might even

do him some good.

Now if Joe had grabbed a spade immediately and run out to the sand-wagon as fast

as his legs could carry him, he might not have ended such a nice summer's day in

hospital. But since Joe was just an ordinary kind of bloke, unable to tell the

future, he didn't, and as a result he did. Because at that moment Harry, the

chargehand over the casting bay came across to Jimmy saying that he was a man

short, he needed a skimmer. At the same time Simon, the Deputy Manager on that

shift came round the corner.

"Everything all right Jimmy? Everything O.K. Harry?" he asked.

"No. I need a skimmer," repeated Harry.

"Oh well, we'll find you somebody won't we?" Simon replied, looking at Jimmy.

"What job are you on?" he asked turning to face Joe, who, as we have said, had

not taken his opportunity to run outside.

"I've put him on the sand-wagon," Jimmy butted in.

Simon looked over towards the small mountain of sand that was already stockpiled

inside the factory. "That can wait," he said. Then, looking at Joe again, "you'd

best go skimming."

Joe was speechless. Speechless because he was scared. Scared because he felt

helpless. The skimmer had to skim the slag off the top of a ladle full of molten

iron using a skimmer, a four-foot-long steel bar with a flat steel disc at one

end, much as you would use a spoon to skim the tea-leaves from the top of a cup

of tea. There were of course differences. First, skimming was hard work. The

iron was poured out of the furnace into the receiver, then into the ladles

suspended from an overhead rail. The skimmer had to pull the ladles from under

the receiver, push them to where he skimmed them, then push them round to the

casters, who in turn had to keep up with the track carrying the newly made box

moulds up from the moulding machines. Moving at a set speed the track rarely

stopped, so that the casters had to push the ladle and pour the iron at the same

time, often spilling it over the track and floor. The skimmer only stopped when

or if the track itself stopped. But worse than this was the heat. It burned your

face and hands, it made you feel as if your goggles were melting and your gloves

catching fire, while the rest of your body and clothes were drenched in sweat.

Yet worst of all were the fumes given off by the molten iron. Fumes that hit you

straight in the face when you pushed the ladle, that burned your throat leaving

even the fittest men gasping for breath.

It wasn't the thought of hard work that frightened Joe, it was the thought,

however much he tried to

push it to the back of his mind, that he wouldn't be able to do the

job because of the heat and fumes especially the fumes. There were days when

he could hardly get his breath on the core plant, days when he wondered how long

it would be before he couldn't even manage that job any more. But what option

had he got? He knew what the mech. was like, how many times in the past ten

years had he heard people told, "If you can't manage the job - get out." If he

told the Deputy Manager about his chest, he knew what the answer would be, "Go

home and come back when you're fit to work"; the problem was that he'd never be

fit for work like that again. Alternatively, if he simply refused to do the job;

he'd be sacked on the spot. There was no embarkation in the mech. Apart from a

few fitters they were all labourers and had to do whatever job they were told.

And Joe just couldn't afford to go on the dole until he was sixty five. All this

flashed through his mind in a couple of seconds. He couldn't do the job; but he

couldn't afford not to. He didn't know what to do. So he stood there speechless.

Jimmy Walsh had realised what Joe must bethinking. Jimmy had worked in the mech.

for over twenty years, during which time he had seen it all and grown both

mentally and physically hard.

He had little

sympathy for his own misfortunes and less for other peoples. But he knew that

although Joe was a willing worker, that he probably wouldn't last very long in

the casting bay. And he didn't see the point of giving someone a rough time

unnecessarily. Besides that he didn't like the idea of the Deputy Manager

shoving his nose in where it wasn't bloody well wanted, much less needed. So he

suggested that Joe change places with one of the young lads on the labouring

gang who'd been given a lighter, cleaner job, arguing that nobody would bother

about such a swap in this case.

Simon however wouldn't be moved. He'd given Joe a job and if joe wouldn't or

couldn't do it, it didn't matter which, he shouldn't be there. "You know what

this bloody gang's like," he argued with Jimmy, "let one turn a job down and

they'll all turn the bloody job down. Let one off because he's sick and two

minutes after they're all bloody sick. Joe's worked here long enough, he knows

the rules, you either do as your told or you go home. Thats all there is to

it."

And that was all that there was to it. There was no court of appeal here. Simon

knew he was right. It was alright being soft, making allowance for this, that

and the bloody other. He wasn't being awkward for the sake of it, he wasn't made

out of iron. But they were a rough, troublesome lot here; give an inch and

they'd kick you a bloody mile; show that you were a bit on the soft side and

they'd play on it, they'd con you right, left and centre. He looked from Jimmy

who was unimpressed, to Harry, who wasn't interested, who had heard it all

before and who only wanted a skimmer; then to Joe who still hadn't opened his

mouth.

"Come on Joe," said Harry turning to walk back to the casting bay, "I'll fix you

up with some gear."

Joe meekly followed and collected his protective clothing; spats, goggles and

gloves. "It'll soon be half four," Harry commented consolingly as Joe

unwillingly set off for the skimming area. He got there just in time to see the

first ladle being filled.

"Are you supposed to be skimming?" the bloke operating the receiver shouted at

Joe. Joe nodded. 'Then don't just fucking stand there, shift this bloody ladle"

he screamed.

Joe hurried under the receiver, adjusting his goggles as he went. He pulled the

ladle a little away from the receiver then changed sides to push it the rest of

the way. But he hadn't gone far before he was bent double frantically rubbing

his head. For a minute he'd thought that his hair had caught fire, since when

you walked near the receiver you walked into what appeared to be a firework

display, a never ending shower of sparks and spots of molten iron. Joe wasn't

used to this, it seemed as if the receiver was aiming at him personally. He'd

heard and felt the sizzle as spots of iron had landed on his hair. Even as he

bent over sparks continued to fall round him. "Here, put this on" shouted the

bloke on the receiver, short temperedly throwing a flat cap at Joe, "and get

that fucking ladle out of the way." Joe grabbled at the hat gratefully, jamming

it onto his head as hard as he could.

"Come on Joe," shouted the caster waiting for his ladle, "we've only got till

half past four," he added sarcastically.

Growing ever more confused, gasping for breath, Joe pushed the ladle to where he

had to skim it. Sweat was already running down his face and back, he picked up

the skimmer, but instead of holding it over the ladle to warm it up a little, he

dipped the cold steel straight into the molten iron. It spat back at him

viciously. Joe dropped the skimmer and clutched the side of his face where a

spot of iron had him him, sticking to his skin, sizzling.

"Shift this bloody ladle," screamed the man on the receiver.

"Go and get the next one," the caster told him, "I'll skim this." Joe did as he

was told.

On and on it went, for an hour, an hour and half, two hours, with the machine

moulders filling every space on the track. Round and round the ladles came, Joe

got no chance to rest, no chance to sit down, even for a minute to rest his

weary legs. He had to keep up. Somebody younger and stronger who could work

faster would have been able to get in front a bit and snatch a minute's sit-down

every now and then. But Joe was neither young nor strong, he had to drive

himself to the limit just to keep up. The bloke on the receiver, who did a lot

of shouting, had started to help him a bit by pulling the ladles a couple of

yards from under the receiver; and some of the casters would sometimes give him

a lift by skimming their own ladles. This gave him the chance to empty the wheel

barrow into which he put the slag; or to clean his skimmer, which became

progressively bigger and heavier as more and more iron stuck to it. Joe cleaned

it by swinging it over his shoulder and bringing it down like a sledgehammer

against an old anvil kept for that purpose. He always seemed to be trying to

catch up. He lost track of the time, moving more and more mechanically.

The noise, the vibration, the crashing, banging roar of the machinery seemed to

get louder and louder, forcing its way into his head, making his veins throb as

if they were going to burst. The heat had become a part of him, he was wringing

with sweat. It ran down his body soaking his clothes, his shirt, pants and socks

were saturated. When he was actually skimming his gloves started to smoulder,

his face and hands felt as though they were being slowly roasted; his goggles

felt as if they were going to melt and the heat from them burned his eyes making

them water. Spots of iron had singed his hair, burned his arms and face, found

their way down his shirt and boots to stick and burn into his flesh. The

strength seemed to have gone from his arms and legs long ago, yet they still

kept going, he didn't know how, he didn't think about it any more. Worst of all

were the fumes, no matter how careful he was he couldn't avoid them. They burned

his throat, stung his eyes, suffocated him, making him fight for every single

breath. He felt as though he was being crushed, his chest just couldn't cope

with the poison that filled it.

Joe couldn't go on any longer. The physical effort, the noise, the heat, the

fumes had taken what was left of the strength from his legs. Gasping for breath

he couldn't breathe, he was choking; his heart was bursting, his head was

spinning, the foundry was rocking wildly. He fainted; falling across the

wheelbarrow full of red hot slag, bashing his head against the wall. Two of the

casters were quick to pull him off the barrow and put his burning clothes out.

He hadn't been burned too badly and, though the gash on his head looked nasty,

"It could", as the Deputy Manager said, "have been worse." Joe was put on a

stretcher, carried to the first aid building, then taken to hospital. He never

went back to the foundry; in fact he never worked again. Who wants to employ an

old man with a weak chest, burned belly and a scar on his forehead?

Len Taylor

(Bolton)

BRISTOL BROADSIDES

Bristol Broadsides has now published ten booklets. Some of the publications come

from writers' workshops; others concentrate on people's history. In the four

years that we have been going we have sold in excess of 25,000 copies of our

books, locally and nationally.

We are beginning to make an impact on the way people see history and writing.

Memory and experience - written or tape recorded is now a crucial part of

local history; creative writing is becoming a vital form of self expression in

council estates and workplaces.

Bristol Broadsides operates as a co-operative, with one full time worker, whose

salary is funded by South West Arts.

We are an active member of the Federation of Worker Writers, and it is important

to our work locally that we are part of a thriving national movement.

For more details about Bristol Broadsides, contact us at: 110 Cheltenham Rd.,

Bristol BS6 5RW. Tel: (0272) 40491.

Children in the

Kitchen

"Out!" said Ma,

"You've gone too far.

I have to tell you

What you are."

"You're cattle on the high road,

Pebbles in a shoe,

Nettles in the garden,

Sugar in the stew

Or any other nuisance

I can do without

Children in the kitchen,

Please walkout!"

Denise Doyle

The Wedding Guest

Lil stood in her pew and looked round at the assembled wedding guests and

bride and groom. "Well" she said to herself, 'There's our Mabel all done up like

a dog's dinner. Whatever made her chose that terrible shade of pink. With her

complexion she looks like an underdone lobster and that chap doesn't know what

he's letting himself in for. Right little madam our Lucy, all done up in that

white dress and her no better than she ought to be, had more blokes that I've

had hot dinners. Takes after her mother. She was fast. Look at all them nylons

she got from the yanks. Didn't get them for nothing I know. Look at our Fred

in his morning suit, and he ain't got two pennies to rub together. Up to their

eyeballs in debt the lot of them. Still, the lad's got a good job and his

mother's a lovely woman. Works in that office block, cleaning, and cleaning's

summat our Mabel don't know much about. The state of her windows! You can't see

through em, and got the cheek to buy new net curtains. Thought they'd hide the

dirt I suppose. Cor, our Fred's gut, its obscene. A good days work and a few

less pints, he'd loose a stone easy. Vicar's looking old. All grey and lined.

His wife looks all right though, done up like a 41/zd hambone. That make up

looks like she slapped it on with a trowel. I love's this church, makes me feel

all holy and religious. Sort of good inside.

Blimey, they'm coming out the vestry and I never even heard em say their vows.

Better stand up or I'll be last out and miss the photos.

Maureen Burge

School

"Tell me Diana what grows in your garden?"

"Goosegogs and taters, please Miss".

"Gooseberries and potatoes, Diana".

"Yes Miss".

"Collect the books please Jane"

'Teachers Pet!"

"Pat's wearin' her Brownie uniform to school.

I'm tellin' Brown Owl of you".

"Jane loves Stephen.

He sent her a note.

"I've got a new liberty bodice,

it's fleecy lined with rubber buttons,

so the buttons won't break,

when Mum puts it through the mangle".

"Show off! show off!"

"My Mum says I'm not allowed ankle strap shoes they're common."

Jo Barnes

Scholarship Boy

He knocked at the door.

"Come in, sit down.

Now what newspapers do your parents read."

'The Pictorial and the Daily Herald, sir."

"Who is your favourite comedian, boy?"

"Max Miller, sir".!!

'Tell us one of his jokes".

"I can't remember one,

but I can tell you one of Frankie Howerd's".

"What does your father do?"

"He's a docker, sir."

Each word a nail hammered his fate,

Their words, his words.

Not grammar school material, they said.

Jo Barnes

The Gardener

Pleasant house.

In a row of council houses.

Windows sparkling, clean white net curtains.

Neat garden.

Hedges trimmed, bright green privet hedges

all one height.

There's a wedding

Happy people walk on a lawn

short grass, no brown mud patches.

Rose tree in centre, pretty rose tree.

Pleasant garden.

One week later.

No green showing, a profusion of flowers.

Red roses, yellow daffs.

Pink carnations.

Pure white lilies, cards attached

Black edged, black print

In living memory, R.I.P.

There's a funeral.

Black suited men and weeping women

Walk through the pleasant garden.

Towards the hearse.

Two months on.

Dreary house no white net curtain

Empty lifeless windows.

Inside, bereft desolate women

Outside overgrown hedges

Grass lifeless, dull earth showing.

Straggly rose tree needs pruning

Sad house.

Unpleasant garden, deprived of care

like the women

The Gardener is dead.

Maureen Burge

That Feeling

Have you ever had that feeling,

you just can't go out?

Do your darling children,

make you scream and shout?

Or have you got a secret

you can't talk about?

Have you ever had that feeling

you're tired bored and worn out?

Do you stay in and moan

waiting for your old man to come home?

Have you ever had that feeling

while there's life, there's hope.

Your brain is not a cabbage

in life there is some scope?

Have you ever had that feeling.

Right! I'm going to start again,

to care about the world we live in

I'm going to learn again!

Now if you had those feelings,

then you're a lot like me

Remember life is for the living.

But you have to live it To be free.

Pat Dallimore

Day of Rest

Sunday get up at eight, get the spuds out to peel

put the meat in the oven

shell the peas, put the cabbage on.

Children up for breakfast, washing on the line

time for coffee, feed the dogs, dinner ready

time to eat, wash the dishes, put away

work out what to have for tea

bath the kids, get the washing in

get things ready for school, no button on the shirt

its time for bed. Why am I so tired

on my day of rest?

I'll be glad to get back to work.

Maureen Natt

Full publications list:

A Bristol Childhood 50p (+20p. p+p) ISBN 0 906944 00 7

Bristol as we remember it 50p (+20p. p+p) ISBN 0 906944 01 5

Up Knowle West 50p (+20p. p+p) ISBN 0 906944 02 3

Looking back on Bristol 50p (+20p. p+p) ISBN 0 906944 03 1

Shush Mum's Writing 50p (+20p. p+p) ISBN 0 906944 04 X

Toby 60p(+20p. p+p) ISBN 0 906944 05 8

Arthur and Me 50p (+20p. p+p) ISBN 0906944 06 6

Corrugated Ironworks 50p (+20p. p+p) ISBN 0 906944 07 4

Fred's People 60p (+20p. p+p) ISBN 0 906944 08 2

Shush Mum's Writing Again 65p (+20p. p+p ISBN 0 906944 09 0

Teaboy's Revenge

Down Trafford Road into Ashburton Road walked Alex Jones, his army gas

mask case with his sandwiches in, swinging at his side. He knew if he didn't

hurry he would miss the bus that went pass the gate of the factory where he

worked.

It was a freezing morning when he stopped under the bus shelter at the entrance

to Trafford Park, to wait for the fifty three. He stamped his feet, cupped his

hands and blew into them. "Jesus, what a morning, if only I had another few

pence I could have gone in the caff for a cuppa". He mind was racing as he

counted the coppers in his pocket without bringing them out. But no matter how

much he counted, he still had only his bus fare to work and back.

Just when he had made up his mind to spend his return fare on a cup of tea, the

bus came tearing around the corner and pulled up at the stop.

"Upstairs, upstairs, there's plenty of room on top." Alex tried to go inside the

bottom deck, "Hey mate, are you deaf? I said upstairs". Alex didn't argue as he

climbed slowly up to the top deck of the bus. Under his breath he cursed the

conductor, "Bleeding jumped up bastard, another of those give me the power, you

can keep the money type."

He settled into a seat next to an old man smoking a pipe. A shiver went through

his body as the warmth of the bus seeped into his cold bones.

A bell sounded. The bus started moving. The smoke from the old man's pipe

descended like a thick cloud around his face and head.

"What're you smoking, bleedin' socks?" he said turning fiercely towards the old

man.

The man just smiled as he drew once more on the pipe, then said, letting another

trickle of smoke from his lips, "No son, it's a bit of twist I got from my paper

shop this morning, good ain't it?"

Alex coughed "I don't know about thick twist, it smells like thick shit on me."

For the rest of the journey they didn't speak. The old man sucked on his pipe,

while Alex coughed. Two more stops and the bus would be outside the main gate of

the aircraft factory where he worked.

For a fourteen year old lad, Alex had a good job. He was brew boy to the men in

the shaping shop, that was where the propellers of the aircraft were shaped from

planks of laminated wood.

The process started with paper thin sheets of wood stuck together with glue and

compressed to make planks, then the planks were cut roughly to the outline of a

propeller and then they too were glued together. The glued planks then went into

large ovens which quickly hardened the glue before finally coming into the

shaping shop. Rows and rows of joiners benches, on each bench a propel lor in a

different stage of completion.

This is what Alex saw every morning. He would walk down the rows collecting the

brew-cans that each man placed on the corner of his bench, with his brew of tea,

cocoa or coffee alongside it. Some of the men had two sided tins, one side for

the brew, the other for his sugar or saccharine, while others had neat newspaper

packages with the tea and sugar mixed.

Alex had his little book with all the men's names entered in it. Alongside each

man's name was either a tick or a cross. A tick meant that the man had paid Alex

three pence, this was the agreed price all the brew boys got. Of course, the

firm paid him wages also, so by and large Alex was on a fairly good wage. Apart

from this, during the week, a man may come to work without a brew, having

forgotten to bring it or because they had no tea at home. In either case he

asked Alex to make him a buckshee brew. For this favour Alex charged an extra

three pence, although to get the brew all he did was pinch a few leaves from the

other men's brews. If a man welshed on his payment, Alex would make sure that

his brew was the last to be made which meant either a cold brew or a brew with

the tea leaves floating thickly on the top of the can, and until he paid, the X

against his name would remain.

Alex alighted from the bus, tucking his hands deep into his pockets and head

bent against the wind, he started to cross the train lines which were between

the road and the factory entrance.

"Hey, Alex.. "

He turned and looked up. "Oh, it's you Jack. Hurry up or we'll be late and have

Greenie after us."

Jack was the brew boy for the lathe shop and Greenie was the foreman over the

whole bay. Both boys hurried towards the security lodge to clock on.

"Did you hear about that twit who brews for the night shift? he's got a raise

and been promoted."

"Who said that, Jack? I'll bet he won't stick at whatever job they've given him.

He'll be asking for his brewing job back."

"What makes you say that Alex?" He put his hand on Jack's shoulder, "It's bloody

obvious isn't it? We were all on twenty two and a tanner. Well, with say about

fifty men each giving him three pence, well he'd have to get a rise of twelve

bob a week and I can't see these tight bastards giving him twelve bob rise. Can

you?" Jack looked thoughtful, "No I guess you're right. What a silly bleeder.

He'll be sorry."

They both laughed Alex said, "I'll see you later in the brew house," as they

parted, each going to his particular section of the works.

When Alex had hung his coat up on the nail on the wall alongside the empty bench

he used for sorting his brewcans, he took out his book. Only three names had

X's. Two of them Alex discarded! one because Alex felt sorry for the guy, and

the other was Big Mike, an ex-wrestler who Alex got on so well with. He ticked

them both, but the third was Phil, this was a guy Alex was always having trouble

with and he hadn't paid for three weeks.

Alex's face was stern as he tapped the book with his pencil. He spoke aloud to

himself while tapping. "Right you bastard, I'm going to give you one more

chance."

He walked down the row of benches until he came to a bench where a small man

with a large hooked nose was.

"Have you got my money for brewing up for you?" he asked. The man turned his

head,

"Are you talking to me?"

Alex opened his book,

"You owe me three weeks and I want paying."

"You cheeky young bleeder, you get your wages for brewing up don't you? now piss

off before I put my boot up your arse."

From one or two of the benches around came shouts of the men there, "Pay the

lad." "You tight bastard." "Give him his money."

Alex stood waiting until Phil the man at the bench moved in his direction in a

threatening manner, then he left saying, "Don't you ever ask for a brew when

your old woman runs out at home, because I wouldn't give you the snot out of my

nose."

The man chased after him, but Alex darted in between the benches and escaped.

Later that morning Alex collected all the brew cans and went into the brew

house. He always made a point of getting there first so he could fill all his

cans one after another under the tap from the boiler.

Only one can sat alone on the side waiting to be filled after he had finished.

His friend, Jack, had brought his cans in while Alex was filling his. He said,

"Hey Alex, You've forgot one." He handed the can to him.

Alex took it off him saying,

"Leave it until the last, he likes cold tea, the

guy who owns that. At least I think he does because he hasn't paid any tea

money."

Jack laughed,

"Whose is it? He'll bleeding kill you."

Alex shrugged his shoulders,

"I can't help it if the water is cold now can I,

eh?"

All the cans were on the bench near the door. Alex placed them in two rows so

the men could pick their own can easily. Right at the tail of the back row was

Phil's can. Alex waited. Each of the men came and took his brew to his own

particular bench. Phil was always one of the first to get his can. He sat at his

bench, opened his package of sandwiches then took the lid of his can.

"You bleeding whelp, wait until I get my hands on you!" He charged down the shop

in pursuit of Alex who as soon as he heard the shout had taken to his heels.

The men were laughing and shouting encouragement to him as he dodged in and out

among the benches. He stopped now and then to shout to Phil, "Pay me my money

and you'll get hot tea!"

Phil gave up the chase. Alex sat with his feet on Big Mike's bench. "Where is

he, can you see him Mike?" Big Mike stood up. Because of his size he could look

down the full length of the shop.

"I'm afraid you're for it kid, he's gone in Greenie's office with his brew can."

Alex was busy collecting the cans for washing when Greenie came behind him and

tapped him on the shoulder.

"I want to see you in my office." Alex continued collecting the cans. "NOW!"

Greenie shouted.

Inside Greenie's office Alex listened to the foreman's ranting, about how he was

paid to brew up, not have the men chasing him in working time. Then he calmed

and said, "I've put you up for promotion, maybe when you get a responsible job

you'll be better. Now go and behave yourself or there'll be no promotion."

Alex walked from the office in a daze, "Bloody promotion more like bloody

demotion!" He had to do something and fast, or he would get an Irishman's rise,

a bloody drop in pay. This was all that bleeding Phil's fault.

Lunchtime came, every brew can was steaming, including Phil's, and when Phil

took his can to his bench he looked at Alex, smiling a self satisfied smile, as

though he was saying "I got you now, you little bastard."

At just before the break in the afternoon, Alex had just gathered the cans when

Big Mike shouted to him,

"I see your mate Phil's gone home sick." Alex smiled,

"Yeah! It must have been something he drank."

Big Mike's face broke into a grin as Alex explained how he had doctored Phil's

tea with half a dozen Bile Beans.

It wasn't long before the story of the Bile Beans travelled round the whole

shop. Alex became a kind of hero figure with most of the men.

When Greenie heard he sent for Alex to tell him that because of his pranks there

would be no promotion for him.

Alf Ironmonger

(Commonword)

Notes Towards A Poem

On Russia

1

Red star night.

A badge in the sky.

Banners at the cross-roads.

Oh Mother Russia,

your past bleeding,

we are driving to the future

in a black limousine.

2

Rubbing hearts

in the lift

with travellers,

an atlas in microcosm,

all telling us,

by their accents,

the rooms

that they were born in.

In the Ukraine Hotel,

the bathrooms drip

with voices

and many tongues

sleep,

with the last words of the day

melting away on their lips.

3

Vodka is as warm

as a kiss.

It thrusts a burning finger

down your throat.

After a few,

we embrace.

Our arms surround

the World.

Warm Russian that he is,

Igor kisses me.

After fish and caviar,

the kiss

tastes good!

He signs away his writing:

To Keith,

who is both happy and sad.'

Another night

spurts into a dream.

In and out of trouble,

people will always

dance.

4

TO A FELLOW WRITER IN RUSTAVI

Last night we swopped our shirts.

They didn't fit our bodies too well

but they fitted our mood exactly.

5

WHITE NIGHTS

The huge spread of Leningrad.

Cold courtyard heart.

The winter is hard,

but the nights are turning,

from black to white,

to red and back again.

6

Circus,

and I'm dazzled;

not by the slender sway

of the supple trapezist

but by the spotlight

of a girl's blonde hair.

Shining from the audience,

she smiles

and all Russia smiles at me.

Such tricks in this moment.

I know I'll never see her again.

7

ZAGORSK

All the wailing

behind fine railings.

The seminary domes like suns

catch the sun

and priests, with long nights in their beards,

harmonize brilliantly.

Their voices,

polished gold,

sound out the walls

as a rocket

glints in the sky.

8

RUSTAVI STEELWORKS

It's hellish hot in here.

Beneath the Earth,

these are

men and women

sweating steel,

forging

futures for

their children.

Steel bars for prisons,

steel bars for playgrounds.

It's hellish hot in here.

Like a heart,

burning.

9

Three swaying silhouettes.

Three bureaucrats.

Along the street,

they joggle towards us.

In their cases,

they carry documents with drink

seeping between the lines.

And now they are laughing,

and now the words are laughing.

They are peace documents.

Messages.

Meant for bottles,

meant for oceans.

Keith Armstrong

(Tyneside Poets)

Hiding Out

Behind bolts and books, Mayfair, school desks, truth crouched:

Cowering, flowering under the table;

Afraid of himself and the class-room's touch.

Running scared on the spot from the Gay label.

In pubs and playgrounds and class-rooms truth lay hid

Beneath a cover tasteless joking, anti-Gay.

Bad Faith in person. Who was he trying to kid?

Himself? His friends? But too late, it happened yesterday.

He stabbed himself so others could not see:

Have you heard how many queers it takes to change

A light-bulb? Four; one to change the bulb, and three

'

To share the experience. Stabbed himself; strange .. .

And then off home to carefully hide Cover Girl

And Penthouse in obvious places to be found

By Dad. And all the time, the Gay flag furled,

Rolled up inside him. Dad found the mags; he was proud.

His son was growing up to be a real man;

Went out drinking, played snooker, darts, read mags:

Strange how kids never change, from tiny babes to football fans;

From string to johnnies in their pockets, and fags.

Then the strain of existing two lives,

Turning to fags to ease his mind and kill time.

He didn't want to think just survive

His feelings. Why was it such a fucking crime?

Incomprehension. What was it the World so feared?

Him? Flights of fantasy ran through his brain

In bed. The only time he ever lived was here.

Masturbation kept him sane, relieved the pain.

Masturbation, the under-cover living

Out of life as he wanted it in day-light.

And now he wanted light with no misgivings.

The time had come to tell the World. And he was right.

Howard Young

(Lancaster)

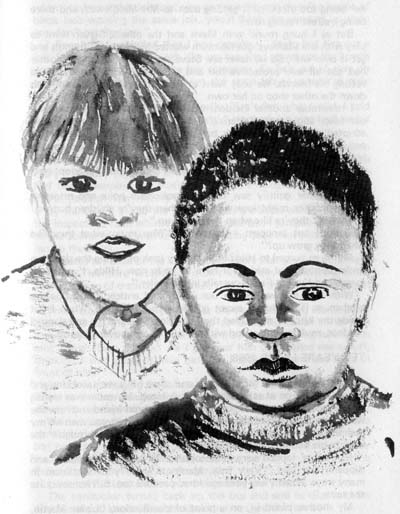

Bad News

1958

When I was little, this was in Reddish where we moved, Mrs. Middlewich from the

fish and chip shop a couple of streets away from us, her little girl died. So

she adopted a little black boy.

Now his real name was Steven but the older kids called him by an evil name; "Sam

Spade." And what's more there were a lot of older kids up Thirlmere Crescent

where he lived. So Steven used to come and play near us.

Actually he was in Mavis's gang. Mavis was a very big girl and she had a two

wheeler scooter with pnuematic tyres. So everyone who had a scooter or roller

skates was in her gang and she was king cos she had the best scooter. Mind you

she was always scrapping with the Rices because they had roller skates but

thought Mavis was a creep. Besides they could outskate and outscoot anyone,

including her.

I longed for a scooter so I could be in Mavis's gang. They always seemed so

clanny and so occupied and intelligent. They were always busy meddling and

meeting in each other's back garden sheds. The rest of the kids were stupid in

comparison to them.

I had a three wheeler bike so I played with the Stanleys who were just loud

noisy kids. Mind you, once all the Stanleys' tribe got mumps altogether and it

was then that I had to play in Mavis's gang. But Mavis took it philosophically

and let me join in.

So we used to play house behind the Jones's motorbike shed. And Mavis and Steven

were always mother and father on account of them being the tallest.

Now Steven had two handicaps: the first was that he was so tall and broad like

Mavis; the second was that he was adopted by the Middlewich couple. They were in

fact quite old and acted like children in order to make their child feel at

home. For example both Mr and Mrs Middlewich read kids' comics and were avid

viewers of cartoons. With Steven they would sit in front of the fire with bags

of crisps, chocolate chewey bars and fizzy pop and their house was full of

imaginary characters added to which there was Billy the Kid: Steven: Banjo Bill:

Mr Middlewich: and Sciatica Nell: Mrs Middlewich. And they would go on all night

like this in the chip shop with the TV full blast.

Consequently when we were all playing house the Jones's shed was full of all

imaginary knocks on the door and strange "who-done-it" conversations with

imaginary folk.

Now Steven used to wear long trousers which was quite unusual for children under

the age of thirteen in the nineteen fifties, but even the long trousers only

came to the top of his ankles on account of his legs being so long. We all

longed for a pair of long pants too, and eventually my mum gave in and bought me

a black pair of playing-out jeans with green stitching.

As soon as I got the pants, I wanted a pair of baseball pumps like Steven's too.

They were canvas with little rubber ankle bumps and I'd seen them in Woolworths

for nine and six. But my mum looked horrified and said, "Oh no, only darkies

wear them."

The effect on my image of Steven was as if I'd seen a bus inverted in a shop

window. I'd come to see him differently or maybe it was the way he really was.

It suddenly seemed to me that Steven belonged in a group which were wild in

Tarzan films and naughty in Noddy books.

Mind you, so what... it was nothing to do with us in Reddish and Reddish

stretched till eternity, even if you went as far as the Bulls Head or

Houldsworth Square I found it astonishing for my mum to keep insisting that we

were still in Reddish. So what if it meant being like Steven if I could wear

baseball pumps, it would be great.

But one day after I come in from playing I heard my dad telling my mum,

"Oh,

don't make such a fuss over it, Winnie."

To which my mum said:

"Go on, you tell him, go on."

My dad started hesitantly:

"Your mum and me think its high time you stopped

playing with Steven. He's not like us. He's different in ways you wouldn't

understand. It's alright you all playing together when you're babies, but its

just not done for older kids to play together. When you grow up thing'll be

different. And Steven won't understand why and neither will you."

So it was OK if I played with Mavis and the rest of the kids but not Steven.

That Sunday morning Steven knocked on our front door.

"Hey," I balled to my mother, "It's Sam Spade."

"Shut up For Gods Sake," she balled. "Look, just shut the living room door and

wait till he's gone. You can play out in half an hour."

Anyway, when I went out they were all there on the corner of Thirlmere Crescent.

Mavis balled out: "What yer called Steven" Sam Spade" through your letter box

for? Look at him, he's been crying."

Steven was rubbing his eyes. "I'm not, I've not been crying at all."

Knowing I was sticking up for my mum and dad I started skipping round the five

of them and singing, "Oh yes you have. Sam Spade's been crying. Sam Spade, Sam

Spade." And then I turned to the other three, Trevor, Raymond and Eric; and

said: "Hey lets run away from Steven. Mum says they're not

like us, pick their noses and eat bubblegum."

With that the four of us ran off and Mavis shouted after us, "Fartin' Martin,

your momma's done yer partin'."

Then Mavis got on her sturdy scooter and gave chase on us with us laughing at

them. But you could tell by her face that she was furious. I got frightened and

my legs were like jelly. I fell behind the"others who'd run down the bin tunnel

of the prefabs.

I couldn't stop in time to make the bin tunnel cos Mavis cut me off, but I

continued running up the street with Mavis at my tail. She overtook and got hold

of my hair and rammed my face into the concrete lamp-post.

My eye and cheek started to swell with the grit and the bruise and I ran home

crying very loud with Mavis shouting after me, "I didn't mean it Martin, we was

only playing."

My mum who heard the howling ran to the front door and Mavis shouted, "I didn't

mean to push him Mrs Golasowski. We was only playing."

I tore past my mum and up the path into our house and buried my face in the

living room settee. My dad who was having a shave to go to the pub at dinnertime

said: "Now whats up."

I said, "It's that Sam Spade, he's thumped me in the eye, he thumped me."

My dad said, "You big bar faced liar. I bet that big girl pushed you. You big

sissy letting yourself be pushed by a big girl. Why you all have to play with a

girl I don't know. You're mard, you want to stick up for yourself."

Well, I couldn't play out for the rest of the day on account of the big black

eye swelling up and leaving me near blind. I stayed off school till the

Wednesday when my mum sent a note saying I'd walked into a lamp-post.

With that, the gang got back to normal and everyone was friends again and my mum

let me play with Mavis and Steven on account of her being too afraid of it

getting back to Mrs Middlewich and there being a street raising row.

But as I hung round with Mavis and the others, Steven went to play with the

Stanleys' cos his mum wanted him to catch mumps and get it over with. So we

never saw Steven much after that. His mother had got all over-protective too and

since the incident had started vetting his friends. We only went to their house

when his mum was down the other shop on her own.

I remember another incident when Hilda Platt put her head over our fence and

started nattering to my mother. Steven's mother had adopted another little black

boy four years younger than Steven, and Steven was showing the estranged little

lad round the streets'. Hilda whispered, "Ah, don't they look nice playing

together. They don't fight like our kids. If I had a three bedroomed, I'd adopt

one, a little girl."

My mother guiltily saw this as a poisonous poke and retorted, "Ah, yes; they

might look nice now when they're children but you know what they're like when

they grow up."

Curious but innocent I butted in, "Why mum, what they like when they grow up?"

My mum turned to Hilda with the dry look of having the situation under control

and said, "I'll have to go in now, Hilda, I've just remembered I've got Fred's

overalls in the boiler."

With that she walked up our lobby and enticed me inside the kitchen as if she

had a secret goodie surprise for me. When I got inside the kitchen she pulled

the door closed behind me and slapped my face, muffling the sound with her

apron, for showing her up.

TEN YEARS LATER 1968

It was when we were all teenagers and some of us were working and Steven stayed

on at school to do his A levels. My mum was sewing and whispering to my dad

about Steven's first girl friend and how she was white. I felt quite rebellious

at this, "Yeah, but you married my dad and he's Polish, think of what we could

have gone through if the neighbours had the mind to be nasty."

My father looked very philosophical in his reading glasses and slippers, and

said, "Very true, Martin. I share your sentiment in many ways. When I was your

age I had passions too. But its not quite the same."

My mother piped in, on a point of clarification, "Listen Martin, when you're on

the dole and you go for a job and there's a queue of black lads wanting the same

job, you'll think the same as us when you don't get that job."

I flew back, reminded that I had passion, "Yeah, but I've got a job. Steven

couldn't get a job like us, our time round cos the bosses don't want to know;

just the bus company. So he's got to stay on and do his A levels so he can get

the same job as us who've only CSE's.

My father piped back pessimistically, "Isn't that what I said, I told you. Now

maybe you can understand." He stuck his pipe back in his mouth and smoked it.

But the most upsetting incident for me was yet to come. It happened a few months

later, like this. I had been to my new workmate's like every Thursday night. He

lived in the flats on Stockport Market. We had been swapping our Motown records.

I came to catch the last bus to Reddish from Mersey Square.

By the time I got to the "Bear Pit" all the buses were lined up for the

inspector's final whistle at twenty past ten. I jumped on the 17A to the sound

of the whistle and the sliding door shut behind me as I ran up the stairs.

Towards the back of the upper saloon were that gang of skin-heads from up

Thirlmere Crescent. I didn't know any of them by name. Just as a gang of

cretins. As I walked past them they were laughing at someone.

There was Steven slumped across the back long seat, stone drunk and asleep to

the world. I wanted to undo his collar to let him breath but I didn't have a

nerve cos they were shouting him to his nick name "Sam Spade." As I got near him

they called me a puff, thinking I was going to help him. So I spaced myself two

seats in front of him.

As the bus chugged up Lancashire Hill they continued calling him. Then as the

bus coasted round into Sandy Lane it started its usual slowly caressing every

bump and rut to gain full effect.

We had just climbed the bridge to Houldsworth Square when the conductor came

upstairs and walked to the back. He shook Steven but he didn't respond. The

conductor shouted in a loud voice, "Hey you, pull yourself together, wake up; or

we'll drop you in at the Police Station on the way to the garage."

I was terrified but Steven was out cold to everyone.

The conductor turned back up the bus and said to us,

"Is there anyone of you

know where he lives that can get him home?"

I just sat there minding my own business, scared of the gang. They were laughing

at "Sam Spade" ending up in clink. I was frustrated that I wanted to do

something but I was afraid of them calling me or maybe the two of us getting

done over. So I just sat there.

Between the Essoldo and the Emporium the faceless gang went downstairs to get

off. I breathed a sigh of relief. Just one more stop to go.

There was just me and Steven left upstairs when it turned into Longford Road

West and the roof started hitting the leaves of the low trees. I wanted to drag

Steven to the stairs but I was scared he might wake up and think something bad,

and scared if any of the neighbours might be downstairs and see me.

I had dithered too long and now it was my stop. I got up with my Motown LPs and

run down the stairs just in time for the door to slide open at our corner.

As the bus wobbled off over the canal brew I kicked myself. I had not acted on

my passion. I had not done what's right. I was Judas. Just afraid and weak and

comfortable to shut my eyes on the world, hoping it would wobble off over the

canal brew. But alone now I was alone with my wretched self. Alone with

uselessness. I now wished all the stupid people alive would laugh at me for

dragging a blackman down the stairs of the bus; or even hauling a cross between

the useless buggers.

I waited on the opposite corner for the bus to come back the other way. Maybe I

could flag it down. Soon the non-lit double decker raced back up displaying

"DEPOT" on the front light. It might have just as well said "POLICE STATION."

I stood out in the road but it just overtook and raced past, a limp brown hand

wobbling back and forth in the back upstairs window.

I wanted to swear, if only I could, that this would be the last time I'd betray

anyone. But gutless and ashamed at my shortcomings I didn't even have the sense

to go round to Steven's mum and say what'd happened.

I told no-one about this. And since then whenever I saw Steven on the street I

looked down or away, afraid to meet his eyes for fear of accusal. For fear of my

lousy self.

John Gowling

(Commonword)

Angela

St Lucia is a tiny island in the West Indies. In London where I used to

live, the white population considered all blacks to be Jamaican. But as a matter

of fact it is further from Jamaica to St. Lucia, than from Liverpool to Warsaw.

I can imagine what a Liverpudlian would think if he went to live in Africa and

everyone thought he was Polish that the natives were bloody thick. Luckily,

the people of St. Lucia are more tolerant.

Angela came to London from St. Lucia when she married a man who'd been recruited

by London Transport. Angela came from what we might see as a rather upper class

sort of family and, labour being cheap there, her family had had servants. So

cooking and cleaning were just two of the totally new experiences offered her by

London life. I think Angela's parents may have been rather shocked by her new

husband taking her off to the mother country. No doubt however they didn't quite

picture it the way it was. They pestered her for pictures of the house, but she

couldn't very well send a picture of the walk-up flat, 1926 corpy style, for

them to show around at home. So she sent a picture of the local Catholic Church

instead, as St. Lucians are nearly all Catholics.

You had to know Angela a long time to find out these things, because she was a

quiet, shy girl. Her husband had not adapted to the strains of the new life and

had left Angela, after producing four children. So Angela buckled down to

cleaning and canteen work, so as to scrape out a living. She was stricter than

the average mother of today, and as a result her four children were very demure

and well behaved, a fact admitted even by some of the more bigoted tenants of

her block.

Although she could feel proud of her children, Angela couldn't prevent being

overwhelming with bouts of deep despair from time to time. Looking around at the

damp, decaying blocks and the surrounding environment, no-one could feel that

they, or their kids had much of a deal. When she got despairing, she would go

more silent than ever. She hadn't many friends work and four kids took up her

time and somehow England had taken away her previous devotion to the Church,

leaving her with little consolation when depression struck.

One day her youngest came back from a message looking really upset. Accustomed

as they were to abuse in the school playground, and on the street, to National

Front propaganda through the door, and to insulting jokes on the T.V. at night,

someone must have said something exceptionally nasty. Eventually they said who.

Angela went straight out and demanded decent treatment for her children, to whom

England was their only home. After an argument, eight stone Angela ended up

throwing herself at the man. This meant a broken finger and a night of terror in

the police cells, terror on account of her kids, that is. But the eleven year

old put them all to bed, and then sat in the chair waiting for her return. Her

mother found her there asleep, when she was let out, uncharged, early next

morning.

After that, she used to get regular calls from a local policeman. He said he

thinks there shouldn't be black people in Britain, but offered his sexual

services in any case, as he told her that 'Jamaican women were alright. Once

black, never back.'

I know she'd have smacked him in the mouth too if she hadn't dreaded the thought

of being taken away from her kids for a long spell inside.

Well, you can't expect even St. Lucians to tolerate everything.

Caroline Williams (Liverpool)

Extract from Back Home

I remember when we first came to England, everything was entirely different.

People passed by without a word. Everyone walked about on the narrow concrete

pathway with the busy roadway on its side. It wasn't at all a free world as you

had in a village where there was all open field and pathways. In England

everything so compact, people walk with their own partners, minding their own

business, no-one to talk to except our own family at home.

Sometimes I would cry for I knew on-one. All we were was one small family in the

home my father bought when he first came to England on his own. There were a few

relations lodging upstairs but still there wasn't enough of us. Not like it used

to be; a big house where you could wander all on your own and a great big farm

you could visit every few minutes. All we had in England was a small garden and

no veranda, everything shuttered, houses with sloping roofs and surrounded by

wall inside and outside. Everything here was full of privacy.

Even though I was only 5% years at the time the memories lie deep inside and the

older I grow the more vivid they are.

Sometimes today I say to myself: "Oh brother, if only you hadn't died we would

never have been here, it's not a safe place to be in." It didn't really matter

when we first came to England but from today onwards things will get worse.

People don't love one another as they used to back home in our village in India.

There's so many problems you face in a world where there's different people from

yourself. You don't feel this at first but as you grow older you begin to

understand the environment you live in and its prejudices.

Even our relations who once lived as one big family have split up into their

small families in their own homes.

As I grow up I realise the cause of all this. Everyone in England works as an

individual and therefore keeps everything in private which wasn't at all the way

our grandparents brought us up. We were lucky in India not to have to face such

things. It is not at all a free world, everyone cares for himself and not his

neighbour.

Well anyway I suppose there is always one place you have in mind that you always

want to be in and I would always want, if I could choose, our village just the

way it used to be with a full house on each corner.

Now that we are in England, I suppose this place is meant for us, for there's

never been a time yet, during the last 13 years, for me to return to India, even

for a holiday. So all I have in mind are those old memories of childhood. Who

knows what I'll think of it when I return to see it again.

Ranjit Sumal

(Commonplace)

The Ballad of

Cuthbert Crout

Young Cuthbert Crout was a naughty lad

Of just ten summers he-

Each day his mum cried,

"Cuthbert! Don't dip biscuits in your tea!"

He would ignore her frequent pleas

And dream of goals to score.

He'd think of fishing with his mates

And cricket on the shore.

While he viewed the soggy heap

Of wet tea-dipped delight,

A rebel crumb fell in the drink

And soon was lost from sight.

He grimly scanned the murky depths

To try to glimpse his prize.

And bravely plunged his paw right in:

An act that was unwise.

For, though he thought he'd caught his crumb.

His hand was tightly held.

He silently began to sink

To where the biscuit dwelled.

The tea like quicksand sucked him down,

And Cuthbert screamed his plight.

His mother sat and sweetly smiled,

And said, "It serves you right!"

Cuthbert and his crumb were lost;

With tea leaves washed away.

So don't dip biscuits in your tea

For you may drown one day!

Katy Best

(Basement Writers)

Michael's Story -Part 4

When two weeks had gone by, Michael had grown accustomed to shopping, eating and

sleeping alone, doing everything for himself and having no one to talk to until

he went to the pub at night, where he had met a few Irish lads about his own

age, with whom he had struck up a firm friendship. Gradually the pub became a

very important factor in his life. It broke the terrible monotony of the life he

led and it helped him to forget about work and the insults and taunts the

'mouth' constantly slung out, as a fruit sorter slings rotten apples. But even

more gradually, yet more irreversibly, grew his liking, even longing, for beer,

and it was this off-shoot of his character which grew and flourished at the

expense of all other facets, like the sucker shoot sucks from the shrub a

disproportionate share of the sustenance garnered from mother earth.

One day as Michael was laying pipes, watched hawkishly by the 'mouth', the

walking ganger came along. He was also Irish, but one who tried to project a

different image from the run-of-the-mill Irishmen who followed up civil

engineering. He wore a neat, though well soiled, steel grey suit, brown shoes, a

collar and tie and a pork-pie hat, set squatly on the top of his head.

"Good morning Mac," he greeted the gangerman in his well cultivated sycophantic

way, a characteristic of all civil engineering bosses above the rank of

gangerman.

"How-awo!" growled the 'mouth' in return.

"Yes. Aye." He looked all round. "Yeah. How are you fixed for men today, hah?"

"Oh, now, I want a few, down on the tip, yes, I want a few."

"Sent a few tapping, did you?" and he laughed in a fawning, sickening manner.

"Oh, now, I'm telling you, I made a few dig out, I did that."

"Well, good on you Mac. Never let it be said! Oh, you're a hard man, Mac." and

again he laughed in a forced, deceitful way.

"Oh, now, I'm telling you, I'll not let 'em get bedded in, I'll not."

"Now, why would you, Mac, why would you. Keep them moving. Don't let them get

cold. Keep them on the move," and he laughed again unnaturally.

"Oh, I will, I will, have no fear of that. Now, I'm telling you, I'll see that

they don't get the crippage. I'll give 'em plenty of exercise. Haaa!"

The walking ganger smiled and shook his head in feigned admiration. "So, I best

send you a few up, then, haa"

"Oh, now, indeed, you can send 'em all this way. There'll be room for 'em all,

and sure if there isn't, I'll soon make a bit of room. I will that."

"Lord, you're a hard man, Mac. Right then, I'll send you a few up."

"Do, as many as you can."

The walking ganger shook his head as he strode away to the next section, while

the 'mouth' watched and added another dimension to his slope in the belief that

he had proved his value as a gangerman.

Michael had heard the conversation and remembered what John had told him about a

man's 'turn' coming along, and decided that he'd be ready for that event when it

came, although he wasn't going to seek dismissal. But he was determined not to

be walked on either, for he had well and truly grown out of that state.

Next morning Michael was on the job at the usual time, and the gangerman came

rolling along in his usual way, accompanied by four new starters, all of whom

were middle aged and wore typical navvys' uniforms.

"Blow up!" yelled the 'mouth' before he had come anywhere near a knot of waiting

workmen. They scurried in all directions, but the four new starters stood in a

huddle nearby as the gangerman opened the toolshed door.

Michael was there immediately and took out a pair of rubber boots, as he had

done every morning since he had started on that job and as he had been so

unceremoniously ordered to do that first morning.

"Where are you taking them?" the 'mouth' asked scathingly.

"I'm putting them on," replied Michael.

"Who said you are?" sneered the gangerman.

"You" replied Michael without a quiver in his voice.

"Me Why, you stinking little liar, I've never talked to you today yet. I've just

left the office, what are you talking about?"

Michael stood rock still. Instinctively he knew it was his 'turn', and he was

determined not to show any signs of annoyance or distress. He dropped the boots

on the floor and looked the 'mouth'

straight in the face. "You told me the first morning I came here to put them

boots on, and I've been doing that ever since."

"You have! Well, by Jesus, it's awful when a shittin' 'greesheen' like you can

have boots and an extra penny an hour, just like a right man."

"I never had an extra penny an hour," Michael returned.

"I never knew anything about that. This is the first job I've worked on."

"Aye, aye, aye, but it won't be the last. Haaa! 'cause you'll soon be . ..." and

he simulated knocking with a clenched fist, ". .. . on that green window."

The four new starters became interested in the argument, but didn't take part.

"And should I have got an extra penny an hour?" asked Michael.

"Haah?" screamed the gangerman. "Should you . . . . ? You're lucky to have been

paid at all. Sure, they should make a stupid 'greesheen' like you pay to be

allowed to work."

"Now, I'm telling you, if I'm entitled to that, I'm having it, whatever you say,

'cause I'm jacking now."

"And isn't it about time, too. Haven't you been here twice too long, you have.

Off you go. You lads, get some tools out of this shed and come down here with me

and I'll show you where to go to work."

The four men looked at one another, but didn't move immediately.

Then they did as they had been ordered they picked up a pick and shovel

apiece, slung them on their shoulders and ambled carelessly to where the

gangerman was waiting for them.

When Michael knocked on the infamous green window of the shabby little office

that snuggled into the huge embankment, the young man who had given him a letter

that first morning to take to the labour exchange to obtain insurance cards

appeared.

"Yes?" he enquired.

"I jacked this morning," Michael told him.

"Ah, you've been working for Brennan, haven't you?" said the young man, screwing

up his eyes to concert his memory.

"That's right," replied Michael, "and I jacked this morning, now."

The young man looked round quickly before he spoke again.

"Hi!" he beckoned Michael. "Here. Don't say you jacked or you'll get nothing for

today. Say he sacked you and then you'll get an hour's pay for this morning.

See?" and he winked meaningfully, confirming the confidentiality of the advice.

"Give's your note."

"Note? He didn't give me no note."

"He didn't! Well, he should have." He turned away from the window and spoke to

someone whom Michael could not see. "Hi! one of Brennan's men's here and he's

not been given a note."

"He's not? Has he been sacked?" asked a husky voice from inside the little

office.

"Oh, yes, he's sacked him, but he's not given him a note."

'The stupid idiot, he's always doing that lately. Tell him to go back and see

that ass, Brennan, get a note off him, bring it here and we'll pay right up to

that time, plus one hour."

"Hear that?" the young man said, turning once more to Michael. "See Brennan, see

that he writes out a note, bring it here and you'll be paid right up to the time

you arrive back here and one extra hour. Okay?"

The young man was just about to close the window when Michael spoke, "And

there's something else."

"Oh, what?"

"Well, I've been wearing rubber boots all the time I've been here and I've got

nothing for it, and I've been told today . . . well it was the 'mouth' who told

me ...."

"Brennan, you mean?"

"Yes, it was he as said I was getting an extra penny for that, and I wasn't, and

I didn't know anything about it, and I was wondering if a man does get paid for

that?"

"Wearing rubber boots? Yes, a penny an hour extra. Hi! hear that? The lad's been

wearing boots and hasn't been paid for them."

"Oh, what's his name?" asked the man with the husky voice.

"Ah, what

"Michael McWanted, Michael

"Oh, yes, there are two of them. Wait a minute."

"No, the other was John, my brother and he left, oh, more than two weeks ago. My

name's Michael and I've ..."

"Just been sacked," added the young man precautionarily.

"Y.yea, yeah."

"See, he's never booked that in," remarked the hidden speaker.

"Oh, now, someone'll have to have a word with this idiot. He's not fit to be a

gangerman. He books in nothing at all, nothing at all. We have to straighten out

his books every time. Well, I'm doing it no longer." A wrinkled, grey face

appeared at the window and spoke vibrantly to Michael.

"Tell Brennan that he must give you a note and that he must write on that note

that you've been wearing boots all the time you've worked here. Okay? I'll see

to the rest," and he snapped the window shut.

Michael walked back again to where he had worked since he had arrived in London,

but the gangerman had gone down to the tip, which was a good distance away.

Michael decided to follow him down there.

The gangerman saw Michael coming and went to meet him. "Yes, what is it you

want?" he asked in the mildest manner Michael had ever known him to employ." I

thought you jacked, eh?"

"Yes, but they said I had to have a note from you. Yes."

"Oh, did they?" the gangerman asked in a manner more like his usual cynical

self.

"Yes, and they said as well that you had to put on the note that I was wearing

boots ... all the time I worked here."

"Oh, aye, and who are they?"

"And they said as well," continued Michael, "that..."

"All right, all right, for Jesus sake, I'll give you a note. Anyone'd think to

hear you that no one ever jacked before.

Sure, they're jacking and being sacked here every day in the week. Sure, I might