|

ISSUE 26

cover size 210 x 148 mm (A5)

CONTENTS

This winter marks ten years since Ben Ainley started VOICES off, and five years

since I began to take over the reins, so it's probably as good a time as any for

me to resign as editor. There is no one single person in line to take over, but

there is a pretty solid VOICES collective here in Manchester and a new editor

will no doubt emerge now that the opening has been made.

The negative reason for resigning the one that towers over me right now is

that my full - time job with its long hours no longer allows me even the

pretence of keeping up with the work on VOICES. In fact, for some time now, the

backlog has been growing steadily.

In the short term, I feel that the Federation of Worker Writers could do more to

help solve this problem, now that it has got some kind of a paid worker again.

VOICES is the one area of the Federation's work nationally which is both

tangible and potentially self-supporting, and more weight should be given to

those two considerations.

In the long term, the real solution to this kind of problem is shorter working

hours then we can all be potential writers. People need to value their leisure

time if they are to fight for more of it, and here VOICES has always played its

small part. But it is equally true that people need much more leisure time to

give them the chance to be creative as opposed to merely recovering in time

for the next day's work. British workers work longer hours than in any other

country in Western Europe. In fact we are the only country where actual hours of

work have increased rather than decreased in recent years. Most trade unions are

trying hard to win their members for changing this situation.

I shall be carrying on as a TGWU branch secretary (which, compared with the job

of running VOICES, is like falling off a log) and, hopefully, starting to write

a few stories of my own again. Meanwhile, the VOICES Editorial Board would

welcome any newcomers who want to get involved and do a job of work.

Finally, I would like to thank particularly those VOICES readers and

contributors whose support has been unwavering over the years, regardless of

whether we have published their own writings or replied promptly to their

letters. Even when you're up to your armpits in paperwork, people like that make

the job seem worthwhile.

RICK GWILT January 1982

The editorial board wish to extend its thanks to Rick Gwilt for all the time and

energy poured into Voices over the past five years. We're sure we're among the

many who hope he will feel able to stay in touch with Voices in the future.

Cranes

Long legged dancers

Stiff in repose

Stately in minuet

Gracefully dipping

Straightening easily

High on tip toes

Where did you see them

These peaceful gazelles

Dancing for Sadlers Wells

Or Royal Ballet? No!

At the dockside

Loading and clearing

Goods from all ships

Choreographed perfectly

Dancing in step.

Iris Warburton

(Liverpool 8 Workshop)

Gullwake

above me

the sky is unzipped

by a slow-motion gull.

Andrew Darlington (Ossett, Yorkshire)

The Wish

At one time I loved you so much

That I wished all the troubles in your life

Would fall upon me, and leave you free of them;

This despite you being another man's wife.

It gave some meaning to my unrequited love.

But now when I see you I cannot understand

What possessed me. Though I wish you no harm

I hope you will take your own problems in hand.

Bill Bartlett

(Bristol)

Ethel

Strange how when you're young, people seem odd to you. It's as if you

notice the most eccentric characteristics and dismiss the common factors. Ethel

was one of those people to me when I was about twelve.

In the mining village where I lived there were 'corner' shops everywhere and

several times a day 'mobile shops' would noisily invade the street. Hand bells

were rung, hooters were pressed, chimes were sounded in order to encourage the

miner's families to part with their money. One of these mobiles, a greengrocer,

was a sight not to be missed. The grocery cart was pulled by an old bedraggled

horse, saved from the glue factory many years before. The father and son who

owned the business looked like the original models for 'Steptoe and Son',

denying the fact that, as far as making money was concerned, they were as sharp

as Soho spivs.

When the cart came into the street one of the men would ring a bell and all of

the smaller kids would run out shouting:

"Glanvilles here, Glanvilles here,

Half a pound of rotten spuds

And a couple of bottles of beer."

On their heels would come the hordes of dogs and cats which always lived in this

type of community, sniffing and waiting for a tit-bit to be dropped.

Glanville's cart always stopped first outside the house where Ethel lived. The

old man would go in for a cup of tea while his son would humbly in Uriah Heep

fashion serve all and sundry. In between their weekly visits Ethel sold

cigarettes, matches, crisps and sweets for them, illegally of course, so her and

old man Glanville always had some totting up to do.

Although I disliked Glanville junior for his stooping manner, rubbing hands and

greasy hair, I felt sorry for him. He never got a cup of tea. The old man was

usually in with Ethel for about half an hour. By the time he came out, pushing

his wobbly gut before him, Uriah would have done the three stops around the

green and be waiting at the end of the road.

I knew Ethel never wore any knickers, we all knew. Mum said she was sure that

Ethel must suffer from dreadful piles. When I first found out it fascinated me.

I used to watch her hobble down the street with her always bare fire-tanned legs

and wonder. Didn't she get cold? She wasn't fat, more like a bumpy, triangular

shape, thin pointed head and face and a large bum with tree trunk legs just

about holding her up.

Her hair always used to amaze me. She wore it severely parted on one side and

then pinned down just above her left ear with loads of hair grips. It came just

below her ears and then stopped suddenly like a large chisel. She was very ugly.

I remember thinking she was a witch when I was very small and I kept out of her

way, especially at Halloween.

So when I thought of the knickerless Ethel there was never any hint in my

thoughts of sex. Not like with Ava Gardener, stories about her being

bare-bottomed used to be funny in that uncomfortable, sex-forbidden age before

puberty. But Ethel, it just never occurred to me.

Number 47, where Ethel lived, was a barren patch. My dad used to clip her hedges

for her, mum gave her plants and showed her how to grow vegetables but still the

garden looked uncared for. The inside of her house was stark. Great bare walls,

always in the process of being redecorated, were kept sickly pale like a

doctor's waiting room. Even when everyone else in our street was up to their

eyes in H.P. for carpets Ethel stuck to linoleum with just the odd worn rug here

and there.

I was often sent round to Ethel's for cigarettes and sweets, but even at twelve,

entering Ethel's domain filled me with apprehension. It was so cold and

unfriendly. Our house was always full of colour, bright wallpaper, carpets and

curtains. Mum had so many payment books she kept a special tin for them. Going

round to Ethels was like walking into a witch's oven, you took your life in your

own hands. Mum said I had too much imagination.

The back door to number 47 was always unlocked. It led into the washroom, then

the kitchen. Oddly enough Ethel was one of the few women in our street who

actually used her front room. In virtually every other house the front room was

kept as the showpiece, only used when visitors came or the priest called. But

Ethel could usually be found in the front. Knowing this I used to sneak in the

back and look round the kitchen, hoping to see something worth telling the gang

about. When I was small I looked for broomsticks and evidence of spells, but as

I got older my looking became less definite. I suppose I was just curious. There

was no doubt that Ethel was a strange one. Her husband had died when I was very

young and, unlike other widows in the neighbourhood, she'd never been out in the

evening since, except at Christmas. I wondered what she got up to, all on her

own, she didn't have a television and she didn't enjoy reading. Perhaps she had

bricked her hubby up in the house and got him out from time to time for a chat.

One Friday, when Glanville's cart was right down the end of the street, my dad

sent me to get some cigarettes. I said I'd get them from Ethel, who only lived

two doors away, but my dad specifically said to go to the cart. I wondered

vaguely if this was because he owed money to Ethel but decided it couldn't be as

he was always telling mum off about H.P. and credit.

When I got out of our gate I could see that Uriah had a large queue on so I

decided to sneak into number 47. I looked round to make sure that dad wasn't

watching me out of the window and then nipped down Ethel's path. I knew old man

Glanville would be there and I thought I might catch them planning dirty deeds

or counting piles of money. I always found it exciting eavesdropping on people

and observing them without being seen. I made a habit of it and innumerable

clouts round the head had never discouraged me.

Everything was quiet in the washroom and kitchen so I stood for a while

listening. I felt like an intruder who could at any second be pounced on. The

door leading to the front room was ajar, I crept up to it and peeped round.

There was a short hallway between the kitchen and the front room, but nothing

stirred. I waited. Faint grumbling sounds and wheezing drifted through so I

gently pulled the door further open and tiptoed into the hallway. At that moment

I heard Ethel speak and I froze.

"C'mon ya daft bugger, don't take all day, what's up with ya?" she said, her

voice seemed wierd and breathless, as if she'd been smoking non-stop since dawn.

"Be patient Ethel, you'll put me off me stroke." Old Glanville sounded worn out.

I could hear a bit of thumping which definitely didn't sound like money being

counted. They obviously were not aware of my presence so curiosity got the

better of me and I decided to find out what they were up to. It might make a

good story for later on. The gang was always interested in Ethel's coming and

goings, she'd been part of our communal fantasies for as long as I could

remember.

I'd worked out long ago, from snooping on my mum and dad, that if I got down on

the floor and looked in a room from cat level I would usually go unnoticed by

the occupants. People don't expect human heads to come from that level, so they

don't notice.

I crouched down, as catlike as possible, and slithered to the edge of the door.

My head was level with the skirting board as I poked it, ever so slowly, into

the room. There, just inches from my face, was old Glanvilles head, his eyes

looking directly at me. His face was bright red and swollen, he was making

horrible grunting noises and his trousers were down around his ankles. Ethel was

lying underneath him. They were having it off!

As we looked at each other I don't know who was the most shocked. I leapt to my

feet and ran for all I was worth. I could hear his voice bellowing after me. "Ya

cheeky bloody bugger, come back here, I'll bloody well wallop you .......

I daren't go home. What with seeing that and not having got the cigarettes. I

couldn't go to Uriah because old Glanville might be out any minute ready to belt

me, he only had to get his trousers on, so I opted for the off-licence down the

road. I could get the cigarettes there and also gain time to think. I began to

feel doom-laden. Dad had clearly had a good reason for wanting me to avoid

Ethels. Now I was in for double trouble.

My stomach felt sick and heavy as I raced through the streets. Would old

Glanville have gone straight round to our house, or maybe Ethel? I didn't want

to think about the reception that might await me. All the while I kept shutting

my eyes tight and pinching myself, but it wasn't a dream. No such luck. I made a

silent resolution never to spy on people again if only someone would get me out

of this nasty situation. Not that I really expected any assistance, because I

knew I'd made and broken that promise at least a dozen times before.

In the off-licence I had an uneasy feeling that Higgs the owner knew my

guilty secret. He kept looking at me most peculiarly. When he handed over the

Woodbines and my change he said: "Time you was home and in bed young 'un, isn't

it?" Then he laughed wickedly like one of those jolly sailors at the seaside.

I started to walk home very slowly, imagining the sort of terrible things which

might be brewing up back at number 47. As I came to the bend I could hear the

sound of Glanville's cart coming down the road. It seemed to be coming very fast

and I had visions of a Dracula type encounter just round the corner. Like

lightening I nipped down the nearest gateway and dropped behind the hedge.

Through the gaps in the privet I watched the cart trundle by - not so fast

really - with father and son in animated conversation sitting on top. Well, that

was one problem out of the way, for tonight anyway.

When I got close to number 47 I crept down Gordon's path and into the back

garden. By climbing over the fences I would get round the back of Ethels

undetected. I could see from the light in her front room that someone was in

there. There was a gap in the curtains and once I got safely up to the window I

was able to peep in. Ethel was there, sitting with her feet up listening to the

radio, cup of tea in hand, fag drooping at the corner of her mouth. Back at the

scene of the crime I felt very nervous, but Ethel looked very relaxed. Maybe I

hadn't been recognised, or maybe Ethel thought that old Granville had been

imagining things! I felt a distinct easing of the tightness round the back of my

neck. Only our house to check now.

Mum had a thing about snoopy neighbours so she always made sure that there were

no gaps in our curtains. Consequently I had to press my head up next to the

kitchen window, which was frosted glass, making sure that I didn't cast a

shadow. I'd been caught like that before.

Everything was quiet. I could hear someone poking the fire, but no sound of

voices. I wondered if this was a good sign or not. In the past I had come into a

silent house after some misdemeanor or other only to be astounded by an

immediate vocal assault. However, I was getting cold so I'd have to take the

risk. Just at that moment a hand fell on my shoulder. I heard a strangled noise

coming from somewhere in my throat as I turned around. It was my dad. "Where the

bloody hell have you bin? It's half an hour since I sent you for the fags!"

Half an hour, was that all, it seemed like weeks! I could always tell when dad

was really made at me and this was clearly not one of those times. He was

concerned, but not angry. Bluffing would probably work, temporarily anyway.

"Uriah had run out of Woodbines so I went to Higgs. I met Eileen on the way and

stopped for a chat. Sorry." Others may call that telling lies but I preferred to

think of it as bluffing. "I were worried about you love, c'mon let's show our

faces to your mum before she calls the police. "He put his arm around me and I

felt weak with relief. It was just like waking up from a bad dream. Perhaps I

had imagined the whole thing and was going to wake up in bed any minute.

Mum was making some tea as we got in. She must have heard us talking outside the

window:

"So there you are ... Ethel's bin round looking for you... " My whole body

stiffened involuntarily but it was too late now. I had no choice. I had to keep

on bluffing and hope for the best. "Oh, has she?" My voice came out too high and

squeaky. Dad looked at me most oddly.

"Yes. . she brought round this box of maltesers for you, your little secret or

something..." Both my parents were watching me intently but I pretended not to

notice.

"I'm very tired. I think I'll go to bed now," I said as I slipped out of the

room.

Ethel and I never spoke about 'the incident' but six months later old Glanville

died. After that Uriah used to go in to 'have a cup of tea' with Ethel and he

always gave me a shilling to keep an eye on the cart.

Kitty Williams

(Ripley, Derbyshire).

Your Poem

Don't wake up

One morning

Vacant as air,

Words dribbling from your casual mouth

Like the slaver of the despairing.

Don't let me see you

Fettered in a chair,

Your grey head

Nodding like a flower

On a broken thread.

I would rather see you

Stagger over a cliff's edge,

Clutching rugs

And a wrinkled pension book,

Than watch you shrug

Life off in favour

Of a dragged-out death and yellowing

Beneath starched sheets

Like an old newspaper.

In the streets

In autumn,

The leaves

Remind me of the doomed senile

Who shuffle in the wake of death.

Promise me you'll say adieu with style:

Collecting young men in Casablanca,

Wearing your wealthy widow's smile.

Maggie Barrand (Basingstoke)

Michael's Story

PART THREE

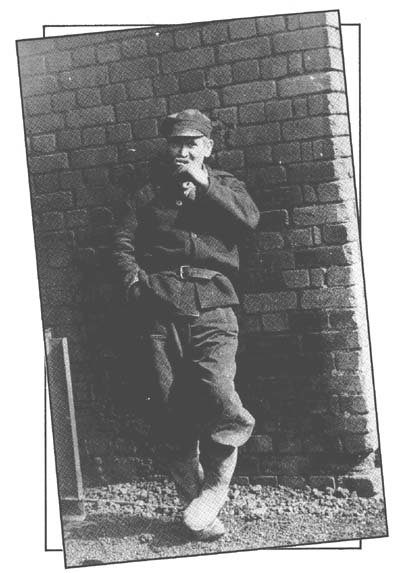

That morning John and Michael were on the job well before starting time, but

already there was a knot of men there, talking and jesting with one another.

John and Michael joined the group, but did not join in the merrymaking. Suddenly

the talk stopped and all eyes focused on the figure that rolled towards them. It

was obvious he either commanded their deepest respect or instilled in them the

most terrible fear, for they all gaped at him open-mouthed.

Before he came closer than ten yards of the silent group he roared at the top of

his rough, hoarse voice: "Blow up, you bastards! Aye, and by Christ, unless some

of you change your style of work today, you'll change your place of work. Haa!

I'm telling you, there'll be strange faces around here before the end of the

shift."

Everyone except John and Michael scurried for the toolshed which the gangerman

had unlocked as he passed. Hurriedly they picked up what tools they needed and

vanished in all directions, watched by the malevolent eyes of the gangerman.

Michael drew his cards from his pocket and hesitantly went up to the gangerman,

"Here," and he offered the cards.

"What's that?"

"Me cards," and already Michael had grown more bold.

"Oh." He put the cards in his inside pocket. "In that hut there you'll find a

pair of long boots. Put them on, 'cause I want you to dig out a manhole for me.

Go on."

"Well, he's not used to this sort of work," John offered, "so, if you like, I'll

dig out the manhole and put him down on the tip in my place."

"Hi! you tell me how to do my work again, and you'll be looking for a fresh

place, I'm telling you. I'm the kiddy here and he and you and everyone else'll

do what I tell them or they'll be knocking on that green little window up there.

And if you don't get off to your work, you'll be knocking there in about two

minutes from now. Now, get off down there to your work, or get off up there to

that window."

John walked away hurriedly in the direction of the tip, while the gangerman

shouted after him: "Hi! You can go that way if you want. No one'll cry after

you, you know."

In the meantime, Michael had raced to the shed and was eagerly pulling on the

long boots. The gangerman watched him from under knotted eyebrows. "Can you not

get them on?" he cried.

"Yes, they're all right, sound."

"By Christ, it's taking you long enough. It must be an awful operation, hah?"

Michael didn't reply but hurried back to the gangerman.

"Come on," he cried, and Michael followed immediately. The gangerman wheeled

swiftly. "Where are you going?" he shouted.

"With you."

"What for?"

"You said you wanted me to dig ... . "

"Without a pick, shovel or graff?"

"Oh," and Michael sped once more to the little toolshed.

"Hooh, may bad luck to the hen;" the gangerman snarled after him.

Michael knew all about a shovel, but he had never seen a grafting tool in his

life. He selected a shovel and pick, then picked up a queer-looking implement,

not unlike a long garden spade, flung them all on his shoulder and hoped to

heaven above that he had made the right selection.

"By Christ, that's taken some time," the gangerman greeted him when he came back

with beads of sweat glistening on his forehead. "If that's the best you can do,

you're no good to me. Come on."

With the tools on his shoulder, Michael followed the gangerman's rolling gait

until they came to a roughly dug hole almost full to the top with brown, scummy

water.

"Down there," cried the gangerman, gesturing with his thumb, like Caesar

demanding the 'kill'.

Michael hesitated, for he felt sure the hole was very deep, and he tried to work

out how to dig in a place like that. The gangerman appeared to walk away, but

stopped suddenly and looking at Michael sideways demanded: "Well, are you

getting into it, or are you getting out of it, which?"

Michael looked at him with fear and consternation in his eyes.

"Jump in!" roared the gangerman, "Jump . . . !"

By this time, Michael had become so disordered that before the gangerman's shout

had died down, he jumped three feet in the air and landed in the middle of the

hole. The hole was only a foot or so deep, but the water splashed in all

directions, and the sudden landing jarred Michael's back. He stood winded for a

few seconds while the gangerman shifted his cap further back on his head, then

slouched away, chuckling to himself: "Hee, hee! That's the first one today I've

shivered the shit in, but it won't be the last. Ha, ha!" He turned again to

Michael. "Now, you better dig that out in big lumps and throw the bloody thing

well back, 'cause when I come back in an hour or so, I expect to see that

finished."

Michael didn't reply, for he was wet to the skin and shivering with excitement

and mental exhaustion. But on his own, he soon collected his thoughts, saw there

were pipes laid on either side of the proposed manhole, realized that the water

was congealed because muck had fallen into the manhole space and clogged the

pipes. Michael first unclogged the pipes, allowed the water to flow away, then

he set about the digging, slowly and methodically, and by the time the gangerman

returned he had dug a neat, square hole more than a foot below the pipes on

either side.

The gangerman looked into the hole when he returned. "Is that all you've done?

Where've you been. Ah, well, now, if that's the best you can do, you'd better

get out of it. Come on, out. Out! Up!"

Michael scrambled out of the hole, his legs like pieces of worn rope, for he was

sure he was being sacked.

"See, them wooden sections there," the gangerman said, pointing to some wooden

shuttering lying about thirty yards away.

Michael nodded.

"Well, after you've had a bit of snap, I want you to bring them here, set them

up and concrete this. That'll finish the job then. Know what I mean?"

Michael didn't reply.

"Hee, hee, I might as well do the bloody thing myself. Anyway, have a bit of

snap now and I'll show you how to go on afterwards. But I'm not going to do your

work for you. See, I don't dirty these, you know," and he flexed the fingers of

both hands. "You get paid for that, not me. When you came on the job, you asked

for work, didn't you?"

"Yes, oh yes," agreed Michael.

"Well, now you've got work, so you better do it, hah?"

"Yes, yes, sound."

"Right, well after snap I'll show you how to go on here, then it'll be up to

you. Anyway, have a bite of snap now. You might be better afterwards.

Michael followed him to an open shed that had been erected by the side of the

toolshed. There on a fire made from roughly cut logs a big drum of tea simmered.

The brew-boy was a man of about sixty, and he felt the lash of the gangerman's

whipping tongue same as everyone else.

"Now, teaboy, have you fried my chops? Hah?"

"No," replied the teaboy, "you didn't order any."

"I didn't order any! What do you mean, didn't order any?"

"You didn't tell me to get you any."

"Well, you know I have some every day, don't you?"

"Yea, but I asked you first thing this morning and you buggered off without

telling me. I can't buy chops if I don't get the money, mite."

"And what about me when I have no money?"

"Then there's no chops, mite."

"Ah, now, now . . . now that's no good at all, no good at all to me."

"Well, that's how it is, mite. I have only my wage at weekend, and that's spoken

for before I get it, it is."

"Well, you should put a bit to one side for times like this. See, I have no

money this morning, so what happens now?"

"What happens! I don't know, mite. Maybe you should put a bit to one side."

Ah, now. . . now. . . . you're no good to me at all, no good at all, you're

not."

"Well, that's how it is, mite."

"Ah, well, this is no good." The gangerman sat down on a log and began drinking

tea from a brown, pint mug.

Other workmen, who had gathered round the fire and were drinking tea from cups,

milk tins and every type of container they could lay their hands on, remained

absolutely silent, listening to the altercation between the gangerman and the

brew-boy and wondering how it would work out. They hadn't long to wait. Soon the

gangerman lifted his head, stared relentlessly at the brew-boy and asked icily:

"Well? What are you going to do about it, then?"

"About what, mite?"

"About this - me having no breakfast, hah?"

"What am I going to do about it! Nothing, mite. That's your lookout."

"Ah, well, I'll do something about it," and he pulled from the inside pocket of

his jacket a crumpled, greasy notebook and a blackened pencil stump. He placed

the notebook on his knee and wrote: 'pay this man of J Brennan gangerman.

"Here, take this to that green window. Now away you go."

The brew-boy walked casually forward, took the note without flinching, read it

and remarked: "One'd expect a gangerman to be able to spell the word 'off." Then

he walked away with a calm dignity that infuriated the gangerman, who watched

with bloodshot eyes. He wanted to frighten that man, but had failed and in

actual fact had frightened himself because he had demonstrated to himself his

impotence to do what he wanted to do. Glumly he sat for a few more minutes

drinking, then suddenly he jumped to his feet and roared so fiercely that his

face turned a nasty blue: "Blow up you bastards! Either to work or to the green

window, whichever you want. One man has gone already and there'll be more before

the day's out."

As one man, every workman jumped to his feet and without a murmur rushed to his

workplace, while the gangerman sat down again and filled himself a fresh cup of

tea.

Michael jumped up with all the others and made off towards the manhole.

The gangerman shouted after him: "Hi, you!"

Michael stopped and turned around.

"I'll be down there in a few minutes to show you how to go on ... as soon as

I've finished this drop of tea. Come here and sit down a minute."

Michael did as he was instructed, but was careful not to stare at the huddled,

grotesque figure who was drinking tea from a brown mug with a noise like an

emptying sink. Eventually the gangerman rose to his feet, stretched and

bellowed: "Ah, God be with the time I was at it, hah! Come on, you don't want to

sit there all day, do you?"

Again Michael bounced with excitement, then followed at a respectable distance.

Michael didn't need much instructing on how to erect the shuttering. He could

see at a glance that it consisted of four sections which slotted into one

another perfectly and were held rigidly in position by interlacing iron bars and

holdfasts. When the shuttering was erected and the bars properly in place, it

was a very solid structure that would withstand any amount of knocking about.

The gangerman examined it when it had been erected and lifted on to four bricks

to allow a concrete bed at the bottom, underneath the shuttering.

He turned to Michael: "The concrete comes to four feet above the pipe invert,"

he said. "Do you know what the invert is?"

Michael shook his head.

"Jesus, you're an awful thick man, you are, thick. Now I'm telling you, you'll

have to shape yourself on this job, hah? It wants levelling and plumbing up.

Have you a level and a tape?"

Michael replied: "No."

"Jesus, you have nothing, nothing at all, you haven't. How do you expect to work

with no tools, hah? Here, you can have mine for today, and remember you concrete

to four feet above the invert. Sure you don't know what the invert is, do you?

Well, it's the bottom of the inside of the pipe, have you that?"

Michael nodded affirmatively.

"Right, four feet above where the water flows, think on," and he walked away,

leaving behind his tape measure and spirit level.

Michael worked conscientiously. He plumbed the shuttering, levelled it, sealed

all the spaces between the pipes and the shuttering to prevent any concrete

flowing into the pipes, mixed a considerable amount of concrete, shovelled

sufficient into the manhole sump to form a good bed, right up to the bottom of

the shuttering, tamped the concrete in the sump carefully, put the remainder

evenly around the sides up to the mark he had made on the shuttering, smoothed

it then with a flat piece of wood and made the job really neat.

Just before dinnertime the gangerman came along. Critically he examined the

completed job, then walked to the shed without passing a single comment.

Michael was delighted. He had passed his first test as a workman in England, so

at dinnertime he ate his sandwiches with an easy mind.

Six weeks John and Michael worked on the section of that job which was under the

control of the 'Mouth'. They travelled together to and from work daily, but

during shifts they never saw each other, for John emptied wagons to make a

viaduct at one end of the section, while Michael dug trenches, laid pipes and

made manholes at the other end. Often they talked about the job and their

gangerman, and whenever they did, either in the digs or in the pub, they never

failed to express amazement that such a poltroon as the person they called the

'mouth' could be so reprehensible and contemptible at all times to all people,

except, that is, the bosses of the contracting company. Yet, even though both

had been scorched by the burning lashes of the 'mouth's' rough tongue, neither

complained, Michael, perhaps, because he was too inexperienced to know who to

complain to, and John because he was too experienced to suspect there was anyone

to complain to.

By this time Christmas was but a few weeks away, the nights had drawn in, the

working day had been cut, and so, of course, had the money. Yet on that job, bad

as it was, there wasn't a man who didn't consider himself a lot luckier than the

hundreds of thousands of men all over the place who had no work at all, and who

had already settled for a very frugal Christmas indeed.

Then one evening Michael had a nasty shock John missed the train they usually

travelled on from Park Royal to Hammersmith. At first Michael wasn't too

worried. He thought his brother had just been delayed and would catch the next

train, so he hung on. But his brother did not catch the next train, or the next,

or the one after that, and then Michael became really worried. He thought about

going back to the job again, but realized it was too dark to do that.

He sat on a wooden, platform seat and tried to think the matter out, but the

longer he thought, the uglier his thoughts became, until he could stand them no

longer. Then he jumped up and with a frightened look on his face, began pacing

up and down the platform, barging into some people, missing others by mere

inches, debating with himself what to do, sometimes calmly and sometimes

hectically, sometimes quietly and sometimes hysterically, snapping his fingers

whenever a solution dawned on him, then swishing his arms about disconsolately

as some hidden snag suddenly appeared, and all the time his thoughts tumbled

over one another in wild confusion. He looked around to see if there was anyone

he could turn to for help, but all he could see was a mass of strained, stony

faces which screamed at him: "To hell with you and your brother! Haven't we

enough to do to look after ourselves?"

Then, just as if someone had switched on an electric light in his head, he could

see a way out he would catch the next train to Hammersmith and his brother

could catch a later one.

He was more satisfied after that and his face lost its haunted look. Yet, when

the next train halted at the station he hesitated. Several times he leaned

forward, rose on his toes as if to walk forward, then pulled himself up with a

jerk and all the time he stared wildly at the concrete steps, hoping and praying

to see his brother running down them to the platform, but that didn't happen.

Then the automatic doors began to hiss, and as soon as he heard that he plunged

forward recklessly, rammed one shoulder between the sliding door panels, and

with his feet scraping along the concrete platform as the train began to ease

forward, he struggled madly to get inside, which he eventually did, with the aid

of a passenger who was standing just inside the doors and saw the lad's

predicament.

"Nearly left it too late, mite," remarked his helper, who was a cockney outdoor

worker, and who had grabbed a handstrap immediately he saw Michael was safely

inside the train.

"Too true, I did, too," agreed Michael, nodding his head and wiping sweat from

his forehead, although it was anything but a warm night. "Sure, he was too late,

too, for the other two," he continued. "Aye, and this one, too, came too soon.

Aha, sure, it's awful hard to judge one, too, hah?"

"Go, blimey!" expostulated the cockney. "More twos and ones there now than in a

guards division. I wonder he doesn't breed from 'em. Coo!" and he also wiped his

forehead with his free hand.

Over and over in his mind, Michael turned his problem as the train sped along.

He felt alone and lost and bewildered, but suddenly he remembered that he was

working, earning wages, saving a bit every week, and his troubles dissolved as

does the hardest snowdrift at the first pout of the spring linnet. He thought to

himself: "I'll be able to send the old fellow and the old lady a quid or so this

Christmas." Then he remembered his brother's warning:"

"Now, don't go doing anything daft, will you? How much a week are you saving?"

"Ten bob. Not bad, eh?"

"N.no, not bad, but sure you may want that yoursel' long before this year is

out, hah? Sure, they're not so bad over there, after all. They have a roof over

their head, the lie-down, and plenty of rough old grub, and now I'm telling you

there are millions of people in this country who haven't that. Ara, keep your

money, well, 'till after Christmas, anyhow."

"Til after Christmas! Sure, wasn't it for Christmas I was thinking of sending

them something. Sure, isn't that the time they'll expect it, hah?"

"Now, hold your horses there. There's a long time yet before the sun starts

shining, at least for the likes of us. Now, keep your money, yet a while anyhow,

'cause you know, somehow, when a man has a few quid in his pocket, he feels a

lot safer, hah?"

Michael put his hand round to the back pocket of his trousers, and felt the

three rolled pound notes lying snugly against his hip and straight away a warm

glow of contentment spread over him. He forgot about John, about the 'mouth',

about his father and mother and began to take notice of people and things all

around him. He became pleased with himself and with life and a slow smile of

satisfaction ran across his face and slackened the tautened flesh on his cheek

bones and around his mouth, the first time that had happened since he had

arrived in London.

When the train pulled into Hammersmith station, Michael's spirits were buoyant,

and he walked off that train and towards the station exit with that unmistakable

litheness of step that prudent youth so gracefully exhibits and indulgent

manhood disgracefully squanders. He started to whistle, but ceased immediately

he remembered the stern warning his brother had given him against all such forms

of behaviour. He walked along the street after that with his eyes focused on the

pavement.

As he walked into the street where he lived, he noticed a lone figure standing

by a street lamp almost outside his digs. He couldn't make out who it was, but

something about the figure seemed to him to be familiar. He quickened his step

and as he drew a bit closer, he recognised the figure it was his brother John

and he was dressed in his best suit and wearing a collar and tie.

"Home early, aren't you, scan?" he called out.

John turned away angrily, for he couldn't bear to be shouted at in the street.

"Finished early?" Michael shouted again, even louder this time.

John didn't reply, but tried to bury himself in the shadow cast by the arm of

the lamppost.

"Something wrong, scan?" Michael continued, but by this time was close enough

for his brother to turn on him with blazing eyes and contorted mouth.

"Well, for the sake of the old fellow's last shag, why don't you grow up, hah?

What the hell do you keep shouting for like that on the street, hah?"

"Jesus, what's up with you?"

"What's up with me! It's what's up with you. Why don't you give over shouting on

the street. Jesus, that's awful altogether."

"Ara, sure I wasn't shouting at all."

"You wasn't! Now that shout then came all the way from Killo-ween. I wonder how

it got here, hah?"

"And, Jese, I wonder, too. I wonder who told it the way."

"Hee, hee, I'm worse standing here arguing with you. But why don't you try and

be like everyone else here. You don't hear everyone round here shouting their

heads off in the streets, do you? Hah? I wonder why has the Paddy to be

different!"

"Well, damn me if I know. I dare say it's because ....."

"Ara, will you give over! And drop them stupid words too. 'Scan!! God above! And

'Jesus' every second word. You don't hear everyone round here saying stupid

words like that, do you?"

"Sure I've not heard everyone round here talking, hah?"

"Hah! That's nearly as bad. You'll have everyone laughing at you if you don't

mind out. Jesus .... aha, hell, it's awful."

"But what happened this evening, sea .... ah, John? You're home awful early."

"Ara I jacked out there."

"Jacked!"

"Shush, will you! Do you want everyone in the street to hear you? Hah?"

"No, but what did you jack for?"

"What! Aha, I had to. Sure, no one could work with an animal like that. Sure

he's an awful ass altogether. Now, it's there now anyhow, so that's it, I'm

finished out there."

"And what are you going to do now?"

"Well, that's what I've been waiting to tell you. I'm going to have a run into

Camden Town to see a couple of blokes who'll know what's going, so here's the

key. You'll have to let yourself in. You're dinner's in the oven and I'll see

you later up in the pub. Okay?"

"Yea, okay, but what are you going to do if you can't find work?"

"I'll see you up there later and we can talk about it all. I must hurry now

'cause I want to see these blokes before they go home. Right?"

"Right, sea.. . ah, John, sound."

John hurried off muttering sarcastically the word 'sound'.

It was with some trepidation that Michael opened the front door, because he did

not like the landlady, and he felt sure that she didn't like him. However, there

was nothing he could do about her feelings, or his own, for that matter, but he

tried to do as his brother had so often instructed. He opened and closed the

door carefully and as noiselessly as he could, took off his working boots, laid

them on a sheet of old newspaper that had been put on the floor in the hall for

that purpose, sneaked upstairs, washed himself and changed into his best

clothes, then came down to the kitchen where the landlady was waiting for him.

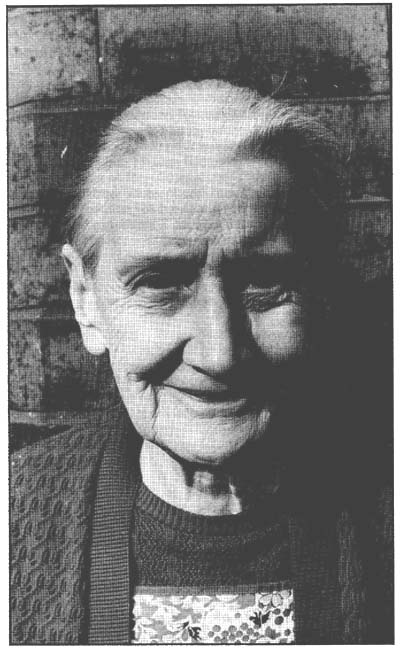

Michael started a little when he first saw her, but then her gaunt face crinkled

into something approximating to a smile and he thought he detected a glimmer of

welcome in her eyes.

"Good evening," she said when she saw him. "Ready for your dinner?" and her

voice sounded worn and weary.

"Yea, yea, yes, ready, yea. Thanks."

She turned towards the oven with a towel in her hand.

"I've kept it on .... I hope it's not burn .... I kept the gas I ..... No, I

think it's all right," and she placed a plate before him and removed the lid.

The pungent smell of cooked meat, boiled vegetables and baked potatoes so

activated the craving of Michael's body for a replenishment of all the energy

and muscle tissue he had used that day as a result of the gangerman's constant

goading and the heavy physical labour he had done, that he lost all his

self-control and attacked the hot meal with the voracity of a starved animal.

The landlady snatched her hands away just in time to avoid Michael's fork as it

dug into the food. She stepped back and looked horrified and disgusted at the

extent of his bad manners. But she soon overcame her initial repulsion, for her

many years of dealing with lodgers had taught her an easy tolerance of all such

incidents.

"Your brother's gone out," she said in a thin, sickly voice.

"Yes, I know," Michael replied with his mouth full

of food.

"I met him outside. He gave me his key."

"Oh, yes, that's right, you haven't one of your own, have you? Oh, dear! And

I've intended to have one cut, but I've been putting it off. Now, with this . .

. Aha, I dunno! Oh, dear!" And she turned once more to the stove to brew tea.

"He's lost his job, you know."

"Yea, he told me. Jacked didn't he?"

"Yes. He has no work now, and it's awful hard to find work these days. Tis. That

must be an awful heathen of a man to make a lad give up his job so near

Christmas and all. He must. I wonder why God allows people like that to be where

they can do that. Ahaa! I dunno!"

"He's gone to Camden Town," Michael said. "He'll find work there all right."

"Eh, I hope so. If he doesn't, he'll have to leave."

"Leave!" Michael screamed so hysterically that the landlady dropped the lid of

the teapot on the floor, but luckily didn't break it.

"Ooh! It's all right, it's not broken. Yes, well, no young lad today can live on

the dole, you know. It's only fifteen shillings a week, and that's no good to

any young fellow. It's not."

"But amn't I working?" Michael reminded her. "Won't I give him money if he wants

it, hah?"

"Yes, I dare say you will," she said as she left two cups and saucers on the

table, one near Michael's plate and the other at the opposite end of the table.

"It's a grand thing to see brothers willing to help one another these days. You

don't see that very often now, you don't. But I suppose everyone has enough to

do to look after himself these days. Ahaaa, I donno what the world's coming to

at all. I don't."

She poured out two cups of tea, one for Michael and the other for herself.

Wearily she sat on a chair at the opposite end of the table, leaned her head

forward and squeezed her eyes as if she wanted to gouge out the sickening pain

in her head. She had a couple of sips of tea and then she said, without lifting

her head and in a voice that had less vibrance than a slack drum: "You won't be

going out tonight, then, now as you're on your own."

"Yes, I am," Michael affirmed as he pushed his empty plate away and drew a hefty

slug of tea. "I have to see sea. . .a, John later on in the pub. Yes."

"Oh. Oh, that's all right, then. I was just going to say that you can stop down

here tonight if you like. I'll leave the light on."

"Oh, thanks, but no, ta, I'm going out."

"Oh. Sure, I'd leave the light on every night, if I could afford it. I hate to

see young lads being made go to a pub every night, but no one can afford to keep

lights burning at night these times. No one. We only just manage to scrape along

as we are. My husband hasn't worked now for months and months. There's no work

for him, there isn't. It's terrible, it is."

Michael nodded agreement.

"I do hope that boy gets a job soon. He's such a nice mannerly boy, too." She

picked up her half-empty cup and walked towards the kitchen door. "I'm going

into the sitting room now, but I'll leave the light on, so you can stay down

here if you want, tonight."

"Ah, no, no, no thanks. I'm going out straight away, I am. Thanks."

"Oh, allright, then. I'll put it out when you've gone. Goodnight!"

"A go.good. . . ."

The frail-looking woman slammed the door shut and left Michael with a

half-formed word hanging from his mouth.

"Jesus, she's not all that bad, neither," he said to himself.

"Jesus, she's ugly though. She has a face now like a quenched lantern. Eh, but

I'll have to be off soon tonight."

That night, he was ready to go out sooner than ever, despite the fact that he

was late home, for although he had been in London less than two months

altogether, his attitude to some things had changed considerably. No longer had

he his original antipathy to going to the pub at night. In fact, he recognised

that the pub was the only place he could remain comfortable. Besides, it was a

social centre where he, his brother and their acquaintances could meet, talk

freely and exchange information about work, wages, lodgings and other matters of

mutual interest to all of them. And even though he was still unable to stand his

corner at drinking, he was no longer stomached with one pint. Always he had two

pints of a night, and on one or two occasions had actually sunk three, but the

most ominous thing of all was that he was developing a liking for the stuff.

Gradually he was settling into a form of life that accorded with his brother's

advice he was forgetting all the tales he had been told about England and

disavowing all that he had brought himself to believe.

True to his promise, John arrived at the pub well before closing time, and

Michael was so delighted to see him that he plunged from his seat and rushed

towards the bar to buy his brother a pint. While crossing the floor in such a

hurry, he overturned a stool and in his excitement became so hopelessly

entangled in its legs that he hopped skipped and stumbled all over the place.

With quiet amusement, John watched his brother's frantic efforts to extricate

himself from the clutches of the stool's legs, and warned facetiously: "Woo,

now! Careful now, boy! Careful, that's it. You could do yourself a terrible

injury like that two terrible injuries, in fact."

Sporting a crimson blush of embarrassment, Michael eventually freed himself,

rushed to the bar and asked his brother: "What's yours, sea. .. ah, a pint of

Main Line, isn't it?"

Still smiling demurely, John nodded.

"A pint of Main Line, please," Michael ordered, but the barman had the order on

the bar in anticipation, and nodded towards Michael and then the pint.

"Oh, ta, thanks." He paid for the pint, handed the glass to his brother and

asked eagerly: "How did you go on, out there? Hah?"

John drank from his glass, hunched his shoulders. "Umm! so, so. Let's sit down."

They walked to the table on which stood Michael's partly filled glass.

"Jesus, tell us how you went on?" pleaded Michael.

"All right, all right, give's a chance to sit down first."

"Yea, yea, course, but how did you go on? Did you find work? Did you meet those

blokes? What had they to say? Did they know anything? Hah?

"Hah? Have you said something?"

"Hi! don't start that, taking the piss. Tell's how you went on."

"Well, I went on the train first, then I went on a bus ..."

"Ah for..... sake! No, tell's

did you find a job?"

"All right, all right, calm down. You're always in a hurry. Drink your pint."

Michael emptied his glass and went to the bar for two more, this time carefully

avoiding all stools.

A few old-timers sitting at the domino table laughed and nodded towards John,

who smiled back in acknowledgement.

So carefully did Michael carry the full glasses across the floor that he never

spilled a drop. "How did it go?" he asked his brother who was already seated,

then carelessly plonked one glass down on the table so hard that the beer

splashed out, over the table and down the front of John's best suit.

"Hold on, hold on," cried his brother as he quickly pushed himself away from the

table and spread his legs to allow the beer to drip from his shirt on to the

floor. "How, did you say? Where more like. God above, I'm soaked .... more so

than a poor millionaire. Why can't you be a bit careful. I bet my buckle turns

brown with this lot. God above!"

"Sorry, scan, I . . I . . I," Michael blurted. "I was just asking how. . did

it.... go?"

After shaking most of the beer from his clothes, John drew his chair up to the

table again, lifted the glass from which the beer had splashed, examined it

critically and said: "I suppose you'll want a full one for this, hah?"

Michael stood a few moments with a vapid look on his face, then flopped into a

chair guiltily. "Jesus, I'm sorry. I just wanted to know how you went on. How

did you?"

"How did I what?" John retorted bad-temperedly.

"How did you go out there?"

"How? Well first I went on a train, then on a bus, then I walked a small bit.

Anything else you'd like to know?"

"Aw, hell! Sure all I want to know is what happened. But you won't say what

happened, will you?"

"Yes, I will. 'What happened'. How's that?"

"Aawaa! Tell's kid."

"Will you give over kidding. I told you before about them stupid words you keep

saying. Give over! You'll make a show of yourself."

Michael sat sullenly for a few moments, but his curiosity got the better of him

and he tried again. "But, John, for heaven's sake tell us how you went on out

.... ah ... there where you went to, hah?"

John drank from his glass, then spread his hands and with an

exaggerated casualness replied: "Well, there's nothing to tell, really."

"But did you find work out there?"

"Sure, I didn't go for work. I told you, I went out there to see a few blokes

who'd know if there was anything going around here, and they told me there

isn't, so...." Again he spread his arms definitively.

"So what?" Michael asked eagerly.

"So ...... that's it. There is nothing."

"Jesus, you were foolish to jack 'til after Christmas anyhow."

"Foolish! Sure a man has no choice. Sure, when that 'shout' thinks it's a man's

turn to go, that man may as well pick up his jacket and walk away."

"A man's turn," Michael repeated, because for some inexplicable reason that word

sent a shaft of foreboding across his vision.

"Aye," continued his brother, by this time having regained his composure and

shed his ill-temper, "walk away. Before he decides that, if possible."

"But what are you going to do if there's no work?"

"Same as I did out there - walk away," John replied defiantly. "That's not the

only job in the world, and this isn't the only place."

Once more Michael felt that emptiness in the pit of his stomach and his beer

tasted sour. He swallowed a couple of times before he spoke again because his

throat felt dry and tacky. "But you'll have to leave the digs, won't you?" he

asked at last.

John drank again, and again adopted an excessive casualness. "Yea, well,

there're plenty digs, if a man can afford them."

"Are you going to go somewhere?" Michael asked in desperation.

John stretched and groaned before he answered. "Yes, first thing in the morning,

I'll be hitting that road harder than a drayhorse, all the way to Ebbw Vale."

"Where's that?"

"South Wales."

"South Wales!" screamed Michael.

This time John didn't rebuke him for his outburst. Instead he looked into the

lad's troubled eyes and saw there loneliness and fear, the same feeling he

himself had experienced when he was Michael's age, and when he had no one to

turn to for help. He leaned forward and spoke earnestly and consolingly. "Naw,

not the place you're thinking about. That's in Australia. This South Wales is

here, well near here, only about a hundred miles away."

"A hundred miles," Michael reiterated as wearily as if he had walked every inch

of that distance.

"Well, that's not far," his brother assured him.

"You'll have to go on a train."

"Naw," remarked John easily, "walk it. Maybe hitch a lift, if I'm lucky."

After this exchange, Michael sat some time in silence, watched by a

dispassionate brother, who knew the thoughts and fears that flooded the lad's

brain. He was about to try and assure him that he wasn't really alone, but then

he thought: "But he is, really, and there's nothing anyone can do about that.

And the sooner he realizes that, the better for himself. "Ah, cheer up," he

said, encouragingly, placing a hand on Michael's slumped shoulders and rocking

the lad gently to and fro. "It may be all for the good. If you have to leave out

there soon, you'll be able to come to me again. You'll be all right."

"Yea," Michael half-heartedly responded.

"Empty your glass and we'll have one more pint, 'cause I must be on that road in

the morning before the drayhorses. Empty it."

"No, honestly I don't think I want any more tonight."

"Come on, empty it, have another. It'll do you good."

"Aye, okay then." Michael emptied his glass and handed it to his brother.

While his brother was at the bar, Michael sat brooding. Being a retiring sort of

lad, he had made few friends, none in London, for the only people he had become

acquainted with in London were people who knew his brother, John, and who had

become known to him through John.

"Oh, I wish I could find out where my other two brothers are," he wailed to

himself somewhat pathetically. "I'm sure .... but what am I talking about? Sure

they may be as badly off as the quare fella. I bet they are, and I bet that's

the reason the quare fella there never talks about them, hah? I bet it is. Now,

the long and the short of it is, I'm on my own, and I'll have to make the best

of it. And I will, too. Sure all the others had to do it, and sure I'm as good a

man as any of them. I am." Again he felt the rolled up notes in his back pocket

and again they had a hypnotic effect on him. He raised his head and smiled

deeply, and then and there he decided that he would never again become dependent

on anyone. "Now, from now on I'll stand up on my own two legs, like a right

man," he solemnly vowed, straightening up, wiping away his melancholy like a

cafe waitress wipes the crumbs off a table, loosened his arms and let his hands

dangle freely by his sides, thrust out his chin and looked around defiantly.

"Aye, and when the 'shout' out there thinks it's my turn, I'll walk away, too. I

will that, maybe quicker than most."

When John returned with the beer he was surprised to see Michael apparently

happy and smiling. Only a few minutes earlier he had left him cowering on his

chair, timid, almost whimpering, but when he came back the same lad was sitting

bolt upright, confident, almost conceited and ready to enjoy himself.

No sooner had John placed the glasses on the table than Michael grabbed one,

drank deeply, replaced the glass, groaned loudly and throatily and said

confidentially to his brother: "Tell you what: they keep a good drop of beer in

here, hah?" He twirled the glass round on the table. "Great stuff, hah?"

In view of the fact that three or four minutes earlier, Michael had to be

persuaded to have another pint, those remarks by him took John so much by

surprise that he could only mutter incoherently: "Oh, yea, yea, hah? Hah?" He

watched his brother closely for the next few minutes and noticed that a

fundamental change had occurred in him. The change was so extensive that it

astonished John, but it also pleased him, for he knew then that Michael would

make out all right.

During the remainder of the night they drank and talked amiably and never once

mentioned work or anything associated with it. Both found, to their mutual

surprise, that there were other, far more interesting things to talk about.

Besides, both felt relieved to put work at the back of their minds for a few

hours, at least.

The following morning, Michael was first out of bed, itself very unusual. He

came down stairs, made both breakfasts, talked casually and unpretentiously to

John when he came down, then just before he went out to work, he shook hands

with John, wished him the best of luck, and from that morning forward he never

saw or thought of, or worried about any of his brothers. It seemed as if, in

those final moments, he was glad to put that period behind him, and that's

exactly what he did.

He also forgot about sending money to his father, and old John McWanted sat by

the fire, more morose and bad-tempered than ever, sucked more vigorously on his

pipe, snarled more cur-like at his wife and cursed the day he ever had a son,

every one of whom had disgraced him by their drunken behaviour beyond in England

and by their selfishness and thoughtlessness for everyone except themselves, for

not one of them cared whether his father or mother lived or died. "Bastards!" he

muttered vengefully to himself, then looked again venomously at his silent,

headscarved wife.

Dead News

Three lines

third page.

One paragraph

in the corner.

Woman raped,

girl attacked.

Not really news,

but it fills in space.

BOLD LETTERS

FRONTPAGE.

Latest edition!

News at Ten.

RIPPER STRIKES AGAIN

WOMAN BRUTALLY MURDERED

and SEXUALLY ASSAULTED!

Only dead women

make the headlines.

Dai Lockwood

(Lee Centre, S.E. London)

The Aunties' House

One approached the Aunties' house along a road of lifeless terraced houses. No

sun ever shone on the street, and in consequence the rooms were always cold and

grey. The Aunts, not related and never referred to in the singular, were four

ageing sisters who kept their front rooms 'for best', but never in fact used

them. They smelt musty and old and were full of ornaments, pictures, and large

ugly furniture, which in turn held stacks of boxes and tins that left us mad

with curiosity. The four spinsters were like jackdaws and never refused so much

as a button that came their way. If something wasn't needed, then it was packed

away, and ultimately it all piled up like an Aladdin's cave.

Upstairs was no different. Large, gloomy, moth-bally rooms. Heavy dark beds with

bolsters, dressing tables with embroidered mats and glass trinket jars, and the

inevitable set of hairbrush and mirror. The bathroom was modern by comparison,

but had a most peculiar smell about it. A mixture of soap, toilet cleaner and

medicines the resulting odour being clean but not fresh; an old ladies' smell,

but without a trace of feminity.

We would be ushered past the 'best rooms' and down the dim passage leading to

the back of the house. Cabbage and a dank smell from the cellar would fill our

nostrils but thankfully, the connecting door would creak open on to a different

world. The door had a stained glass window in it and it heralded what was to

come.

Here was the sunny, warm heart of the house. Furniture still old but lived in,

colourful plates lining the dressers, plants and budgies everywhere, and an

overindulged dog thundering around in welcome. The room throbbed with life.

This haven was the Aunties' house, not the austere front of it, nor the dismal

bedrooms aloft. This was the room rekindled in memories along with our affection

for these dear 'pretend' Aunties of our childhood.

Janine Rankin

(Lee Centre, S.E. London)

The Song of the Wheel

1.

When earth was young and oven-fresh

It whirled in harmony

And mighty mountains marched above

The brewing-bowl of sea;

Then life was sparked; and buds burst forth,

Beasts swam and soared and ran;

And nifty, bright and youngest yet

Came elder brother, man.

Sparked fire, split seed and roasted grain.

Gut caves against the cold;

Watched crawlies crawl, and gave them names.

Watched way that rivers rolled;

Then turned his hands to smite, to break

The back of tree and soil,

Set fire to lick up life, lay waste;

And labour turned to toil.

2.

They are building a city and tower to reach the sky;

It is noon, and all the slave turns in his mind

Are the sun, and the foreman's lash, and that sleep is kind;

He gasps and hauls, and the salt sweat stings his eye.

And the mason is hewing a king's great deeds into stone;

The goldsmith is fashioning gold for a rich man's tomb;

The weaver's hands speed deftly on the loom;

She is weaving a cloth that is fine, and will never be her

own.

3.

It is her first day at work;

The dragon chained in the boiler-room is making a terrible

din;

He is running a race with the conveyor belt

Which he can never lose or win.

The parts come at him like a boxer's blows;

With his hands he wards off each punch to the nose;

His left, then his right; or is it the other way round?

His head spins; he sees parts in the air, the ceiling, the

ground.

He dreams he is taking a swim

In a gigantic glass of beer

But he must keep his mind on his work

Or he'll be out on his ear.

4.

Man spreadeagled

Bound on wheel,

Each limb chained to

Rim of steel.

Wheel ablaze is

Whirling round;

Chained man writhes but

Makes no sound;

Snaps steel;

They fuse in fire;

From leaping flames

Leaps higher

Man-like form,

Sparks of white

Shedding, dances

Dance of light.

5.

Outside the birds are singing;

The machines are singing too.

A sparrow watches with wonder

What the workers' hands can do.

Close-knit in the bond of freedom

They create with brain and hand.

In the furnace they forge the future,

Who are masters now of the land.

Savitri Hensman

(Hackney Writers)

Seen at Divis

Takes a swig

Six year old

Torn jersey - dirty jeans -

Grubby face of six year old,

Drains the bottle,

Holds it Throws

Means

Of showing hate

Bottled frustration

Marrow of bone

Rival sensation

Six years too late

Release is found

In bottle stone

(You question?

Six year old so enmeshed

Father brother

In the Kesh)

Crash of glass

Smashed on Pig

Another bottle

Another swig !

Avila Kilmurray

(Belfast)

Street Games

Dusk had set in when the game began.

Behind houses moonlight glowed in broken glass

Set in the walls round the backs of factories.

A cat screeched, leapt off over gardens.

Gutters full of kids in rags

Hiding from bedtime, letting dreams begin.

Moonlight on gravel & green scraggy weeds,

A train on the bridge doing a ton

Off into the night. In a backstreet pub

They used to serve us beer & cider;

Heady with night & blood & alcohol

We set off roaming Coventry's alleys.

And we ran through gardens swopping gnomes round,

Threw bricks at humming streetlights,

Crossed the tangled lines of the railway-yard

Under a bridge past red iron railings.

Up a black fire-escape to a warehouse roof

And down by a truck left in a yard,

Made its cab roof dent & ring.

Climbed a great spiked gate, left the guard-dog screaming.

Once we walked miles on the railway-line

High up on viaducts, blasted by the wind,

With the streets far below & the city's lights

Thrown out over the hills like constellations.

The city's night was our toy, our battle,

It always began in that smoky bar,

Then wound off round those narrow alleys.

The city's bloodstream, the back of our hands.

One alley stopped at a black brick wall:

we pulled each other up, a twenty-strong gang.

And swayed along, a nightmare tightrope-act,

A Chinese monster between the gardens.

My foot smashed through a greenhouse roof.

Dogs Jumped up from their dreams growling murder.

Bedroom lights came on like sirens,

Scared neighbours bellowed or just gazed.

But they couldn't see. You don't care

For their sleep & their wives & their alarm-clock dawns

When the world is a mouth with big teeth that beckon

And the heavens are littered with stars.

In the morning buses left for school,

Our eyes blurred, fog round the spires;

And people's gardens were taken over

By each others' gnomes, looking guilty & strange.

Bruce Norris

(Basement Writers, London El.)

The Milk Run

"Wouldn't you like to try .... ?" the nurse's voice was thick with coaxing, her

eyes offering support, but Janie shook her head and looked away from the

instantaneous change in the girl's face. Now she had turned to the trolley and,

in a single movement, held bottle, napkin and hot water jug towards Janie, no

longer looking at her.

"I have to work ..." Janie ventured by way of excuse.

The nurse shrugged and pinned her smile on the occupant of the next bed where a

woman with enormous blue-veined breasts was grinning at the jawing infant

suckling there. The child's face was covered by the bloated pear of the breast

he was joined to and meek gasps punctuated his efforts. The woman laughed.

"Hungry little bugger, ain't he?" she said to the ward at large, and then

settled into the pillow with the cocoon of her child arched over her horizontal

body. Janie stared at her and envied her the absent-minded confidence she

radiated. Janie held the bottle clumsily having nowhere to set it down while she

arranged her own infant in her crook, and looked after the nurse's back

longingly. The nurse was at the side of another bed, speaking in that calm croon

to the girl there. The girl was nodding her head cautiously and Janie saw the

nurse set down a bottle with a triumphant smile and begin to undo the straps of

the girl's gown, baring the small breast which pimpled immediately in the cool

air of the ward. The nurse lifted an infant and pushed its face into the

protruding nipple, wedging her finger between its shut mouth and opening the

lips over the nipple expertly. Janie saw the child tighten, make fish breaths

and begin to howl. The girl drew back, nervous, and the nurse tutted and pushed

her forward again.

"You must persevere. It has to be learnt, you know," she said briskly and sat on

the bed to watch. The girl tried again, this time arranging the child's mouth

herself but the child did not suck and the girl looked a question at the nurse.

"Try expressing a little milk," she offered. The girl squeezed her breast until

some milky droplets pearled her nipple, then smeared the drops onto the child's

lips. The child shuddered and howled the more at the tease and the girl shook

her head. The nurse came to her side and manipulated the pair again, this time

squeezing the breasts into the mouth and pressing rhythmically until the milk

was spurting into the tiny aperture. The child gasped and swallowed, wailed and

swallowed, wailed and swallowed for ten minutes while the nurse pressed its meal

into it and the girl lay back tense and near tears.

"Now the other one," the nurse said, holding the child at her shoulder while the

girl exchanged breasts slowly, pleading in her eyes. The process was repeated,

the nurse acting as mechanic between two ill-matched parts. All the time she

crooned at the girl, saying small comforting things as she pumped, calling the

baby's name, praising the meal he was getting, saying the girl was good, good.

At the end she put the child back into its cradle and handed the girl a pad.

"Next time, he'll have the idea, I shouldn't wonder. Now you must keep those

breasts perfectly clean. No drink, no high flavoured food. Plenty of liquids,

milk as much as you can. Well done, mother, it's the best start he could have."

The girl looked miserable as she dressed herself and the nurse moved off

straight away, brisk with duty to be done. Suddenly the girl burst into tears

and sat there sobbing into her hands. The fat woman next to Janie noticed and

called across to her.

"Never mind, love, you'll get the hang of it. Four of them, I've had, and fed

them all. Have a good blow and cheer up! What's your kiddie's name? Your first,

is it?"

Her large warmth reached the girl who pulled herself together with a trembling

effort. She sniffed, did things with paper hankies and called back with a

wobbling voice.

"Sorry, I don't know what came over me. It is my first and his name is Jeremy

Arthur. He was 8 Ibs. 8 ozs."

Her child back in its cradle, the fat woman hauled herself out of the bed and

slappered in her backless slippers across to the girl, drawing her wine silk

dressing gown around her tyre-like body, leaving a deep bowl in the covers where

she had lain. She sat heavily on the girl's bed and flinched as she did so,

muttering, "Bloody stitches!" as she did so. They were soon talking quietly

together, well met since the fat woman was all mother and the girl much a child

still. Janie watched them talk and would have liked to join them but knew her

presence would have unbalanced the conversation. She was in more of a mess than

the girl was.

Her breasts were hurting her. She had woken up in pain that morning, feeling her

breasts like dull weights on her body, hard as bone with the undrunk milk

swelling their every cell. When she laid a finger on them they flared into hot

pin-cushions, passing little shards of pain from one pin-point to the next until

she nearly screamed with the agony of it as the whole breast throbbed and

pricked on. So she had tried to lie still with her arms held away from the sides

of them, folding the covers down over her belly so that no weight rested on

them. When her breakfast arrived she could not face the ordeal of sitting up to

eat it and had suffered instead the stiff face of Sister lecturing her about

"keeping her strength up" and entreating her impatiently to "eat lest she have a

blockage". But she could not and since she knew she must go through this pain,

she did not explain but listened in alarm as Sister warned an enema at her.

Janie had to raise herself to feed the child and this she had accomplished in a

terrible quarterhour, an inch at a time, one side then the other, using her arms

to lever herself up. Every time she jerked upwards both breasts burned and

pulsed and she had succeeded drenched with sweat and tears. She had had to feed

the child at a distance, holding her away from the comfort of her breast in a

cool embrace of her forearm. A box of tissues began to slide off the bed and

Janie reached automatically to save them. The explosion in her breasts drew a

howl from her that turned every head in the ward towards her, and she could bear

it no longer but let herself sob without control until a young nurse came

running in alarm to her side.

"Please help me, please help me," she cried into the teenager's chest as the

girl laid her down. The girl's eyes were wide with concern.

"Sh, don't cry. What's the matter?" her hand was reaching for the bell above

Janie's bed. The bell would bring a doctor.

"It's my breasts," Janie cried.

The nurse halted in mid-poke. She touched Janie's left breast gently but it was

enough to send the hot needles spinning.

"Poor thing," the girl soothed," you should have said. I'll bind them for you.

We can't give tablets any more. They had oestrogen in them and you can get blood

clots. Shh. I'll get some cloths for you." She moved off fast and Janie lay back

with the tears running into her ears as she waited, calmer now that something

was happening. The fat woman's face appeared above her.

"Breasts?" she asked knowingly "Murder, isn't it? Never mind, love, they'll

truss you up like a turkey. Never had it myself but I've seen some horrible

breasts, like lumps of cement. First one, is it? Enough to put you off, isn't

it?" she chattered on and Janie let the words roll over her, grateful for the

reassurance the fat woman s expertise allowed her. The nurse came back with a

trolley and another nurse. They screened her bed leaving the fat woman inside

with her and between the three of them they raised Janie into a sitting position

without too much pain. The nurses began to wind long white cloths around Janie,

starting at the shoulder and working gently further down onto the breasts until

their tender mounds were tightly held in a firm embrace. All the while the fat

woman chucked and nattered into her ear, taking her mind off the thumping of her

breasts. Janie began to feel less weepy and to listen to the woman as she spoke.

In a lull in the monologue she asked a question.

"Why is it so awful? Stitches and sore breasts, feeding and blood all over the

place. Don't you mind?"

The fat woman laughed at her and put a large arm around her.

"Listen, pet. I kick myself silly every time I get pregnant. But you don't think

of all this at the time," she winked at Janie, "this time I was wild. Last thing

I wanted was another kid. I've got blood pressure, you see. For about a month I

lay in bed cursing me old man, not that he knew, but blaming him all the same.

But you learn, you know, there ain't nothing you can do about it. You just have

to put up with it all, jags and being sick, and after you leave here, the good

things roll in. Taking it out for walks. Family admiring it, You'll see and I'll

tell you something else, you'll be back here soon enough too!"

Janie smiled at the fat woman who was laughing again, her fleshy cheeks holding

the high smile up, her eyes already moving across to the other girl's bed in

case she should be needed there again. But the girl was sleeping.

"Thanks for talking to me. I was feeling lonely," said Janie. The fat woman

turned back to her, her face suddenly serious.