|

ISSUE 25

cover size 210 x 148 mm (A5)

CONTENTS

EDITORIAL

25 is traditionally a number that gives

rise to much back-slapping and nostalgia, and even if it seems unlikely that Her

Majesty will grant us all an extra day's paid holiday in commemoration of VOICES

25, why should that deter us from looking briefly at the ground we have covered

since our first issue and paying tribute to at least one of the people who

helped us arrive at our silver jubilee.

In Ben Ainley's first introduction back in 1972, he explains how the magazine

arose from an 'English class' he conducted 'to discuss literature on the basis

of a Marxist analysis and to encourage free and original expression by members

of the class,' He commends the magazine to the 'Labour and Trade Union

movement', and goes on to say a word or two about the choice of 'Voices' as our

title: 'We felt that we had not yet achieved a single purpose; our writing was

not yet a manifesto or a call to action, but a series of individual utterances.

Later perhaps a more unified and challenging character may emerge.'

The type of 'class' conducted by Ben has been to a large extent superseded by

the many writers' workshops that have developed over the past decade or so. The

fact that most of these groups have rejected the idea of a class and a teacher

in favour of a more democratic and collective approach is one mark of the growth

in self confidence of the worker writer movement. (The formation of the

Federation of Worker Writers & Community Publishers, now the magazine's

'proprietor' is another.).

And rather than the production of a manifesto or a unified call to action, we

have seen in the pages of VOICES an increase in the diversity of subject and

style of writing. In VOICES 25, we regard the inclusion, for instance, of the

second part of Mick Weaver's Michael's Story, dealing with the experiences of a

young Irish immigrant and based on Mick's own life, alongside Ante Natal People

by Vivien Leslie, dealing with an experience common to many women today as a

strength. Both pieces challenge us because they speak to us in highly individual

voices. What we have seen over the past decade is a shift from the idea that a

poem or a story should simply serve a political idea, to the idea that through

our writing we can explore the whole range of working class experience in our

society. In other words, the greater the variety of subject, regional accent and

humour, the nearer we get to understanding our world.

Of course, this change has taken place in a wider context. Whereas even ten

years ago the political arena was occupied almost exclusively by parties and the

trade unions, today we also have the experience of a strong women's movement,

black and gay organisations; we have seen young people develop a strong and

independent culture which in the case of the ANL, for instance, has had a

political dimension; and we have seen a growth in left wing and working class

cultural organisations such as alternative theatre, bookshops and the worker

writer movement. All these groups have in some senses fed off each other as well

as presenting each other with challenges to traditional attitudes. Another

feature has been the apparent crossing of traditional class barriers in a number

of cases, for instance within the women's movement.

In a discussion article in this issue of VOICES, Jimmy McGovern raises some of

this as it affects the worker writer movement. The editorial group of VOICES

disagrees with many of Jimmy's conclusions. In particular he questions the

admission of WOMEN AND WORDS, an all-women's writing group, into FWWCP which

VOICES supported at the Federation AGM. As we see it, many women (and for that

matter blacks and gays) are likely to see themselves in terms other than

traditional class ones. For this reason, to exclude an all-women's group would

be to exclude many working class women from the worker-writer movement. This is

in addition to the argument that women, or black, or gay writers are subjected

to restrictions similar to working class writers. Nevertheless, we do believe

that the central points of Jimmy's article need discussing thoroughly by the

worker writer movement. The distinction which he makes between FWWCP as a

cultural organisation and other organisations which are primarily political is

an important one. And the relationship between a working class organisation

which the Federation largely is, although its constitution admits socialist

groups, and other groups of writers is something that still needs to be thrashed

out. It is significant that the group which agreed most strongly with the views

expressed in Jimmy's article is the NETHERLY AND DISTRICT WRITERS WORKSHOP which

contains many working class women.

It may be that after some of these issues have been discussed further by the

Federation as a whole, that we will want to look again at our constitution. Some

of us at VOICES feel that the condition of membership of having produced or be

in the process of producing a publication actually operates against those

solidly working class groups who without the advantage of an experienced

organiser (a WEA tutor for example) are struggling to get themselves off the

ground at a time when membership of a national federation would be of great

benefit to them. We may wish to consider two categories of membership, as some

other organisations have, with full membership for those groups who meet the

existing requirements, and associate membership for other groups with whom we

have a lot but not everything in common.

Unlike the Royal Family then, VOICES is not afraid of controversy during its

silver jubilee. We hold to the old maxim that debate strengthens rather than

weakens. We hope that you enjoy this issue of VOICES which, apart from the

pieces already mentioned also contains work by the TOTTENHAM WRITERS WORKSHOP

which is currently applying for membership of the Federation and by WOMEN AND

WORDS.

Phil Boyd

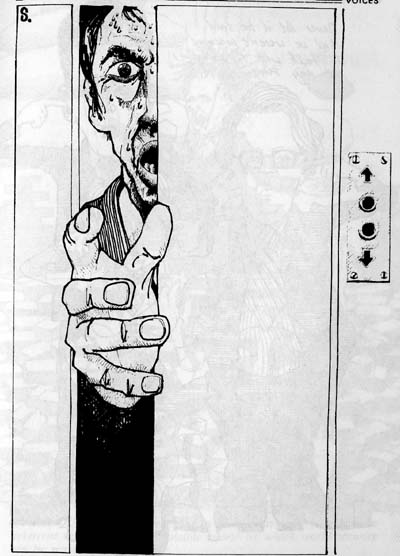

THE INITIATION

Donny leaned back against the wall in Bride Street, his hands in his trouser

pockets, his eyes closed, and began his favourite day dream. The noise and

squalor of the street began to fade away, even the voices of his friends grew

quieter, as his fantasy world of the great pop singer took over. He saw himself

coming through the stage door of the London Palladium to meet adoring fans, and

even Rose, his current steady, had to join the queue to talk to him.

Suddenly his dream exploded and he found himself face down on the pavement. He

shook his head and started to get up, but just as he got to his knees he felt an

almighty blow between his shoulder blades. He first thought that one of his

friends had hit him, but now he began to feel frightened and thought that the

"Eagles" had arrived on their territory. He moved his head so that he had a

better view and saw not the gay threads of the "Eagles" but lots of blue clad

legs and booted feet. He heard a loud voice saying, "Get up you little bastard"

and once more he got to his knees. Suddenly someone grabbed the back of his

collar and dragged him up. He found himself gazing into the eyes of a

police-man. He was pushed back to the wall and found he was lined up with

several of his mates. Jono said to him, out of the corner of his mouth, "Lean

back against the wall and keep your hands over your belly" He started to ask

what it was all about, but as he opened his mouth he was pushed hard in the

stomach. He felt sick, and started to protest about it but Manny hissed at him,

"Cool it".

He sneaked a sidelong glance at who else was in the line-up and saw that all six

of the lads that he had started the night with were lined up against the wall.

He was now good and mad and the frustration of not being able to shout and

scream out his anger was making him sick. He was just about ready to have

another go at demanding to know what was happening when the "paddy-wagon" drew

up. The coppers were standing around the group of lads. Each grabbed hold of a

lad.

Donny was grabbed by the big fella who had been standing right in front of him.

Donny squirmed in the copper's grip, but he was grabbed round the neck and he

felt his air supply being cut off. He was wrestled to the back of the wagon, and

the doors were thrown open. The wagon already had two occupants, both drunk, and

one of them had vomited on the floor. The sight and smells of the wagon hit

Donny as heavily as the earlier punch, and he reared backwards, but the copper

had a very firm grip on him and a second copper came and got hold of him.

Between them they threw him on to the floor of the wagon into the mess that was

there.

Donny was so mad by this time that he was ready to take on the whole police

force. He began to swear and curse, but before he could get his hand on the

copper Manny and Jono had been thrown in beside him. They each got hold of one

of his arms and held them so that he wouldn't hit the jeering face of the

copper. The door slammed shut. The tears of frustration and rage were pouring

down Donny's face and Manny said to him, "You've got to keep cool man. The pigs

just love an excuse to beat you up. Don't give them one."

Donny said, "What's it all about. One minute we're standing on the corner

rapping and the next taking a ride to the Bridewell?" Jono said "We're busted

for drugs."

Donny said, "We haven't any," but Manny replied, "We will by the time we're

charged." The drunk in the corner began to sing, "I'll take you home again

Kathleen," and the bobby driving the wagon shouted, "Keep fucking quiet in

there."

Manny carefully explained to Donny what the form was, that the coppers would

search them at the police station and probably come up with some weed in a screw

of paper. It depended who was on duty whether or not there would be any other

charge, but they must all keep their cool no matter what was said or done to

them or they would be charged with assault on the police.

Donny listened carefully. Manny had been sent down twice before and knew what

went on but he had never seen the inside of the Bridewell. Jono wondered if they

would get bail, but Manny thought it unlikely. Only then did Donny remember his

old lady. She would murder him. The thumps he had taken from the bobby would

seem like love-taps by comparison.

They arrived at the Bridewell and the backdoors of the van were thrown open and

Manny, Jono and Donny started to get out. The coppers made a grab for each of

the boys, pinning their arms and dragging them through the doors. The Sergeant

behind the desk grinned and said "You've got a good bag there. What are you

charging them with?" The copper holding Manny said, "Unlawful possession of

drugs for this one Sarge." Jono's jailer said, "Same here", but the one holding

Donny said, "Obstruction and assault on the police".

The sergeant said, "They don't smell any too good, so hurry up and let's get

this over". Donny heard with growing amazement the story that the bobbies were

telling the sergeant and was just starting to protest when Manny kicked him, so

he shut up. The Sergeant asked them each for their names and addresses. Manny

gave his sister's address, but Jono made up name and address. Donny was too

frightened of the whole scene so gave his correct name and address.

The Sergeant asked if they had been searched and the copper who still had hold

of Jono said, "Just look at the state of them. I don't fancy doing a proper job

until they have cleaned themselves up, but we frisked them on the street and

here is the cannabis we found on them". Just as Manny had said two small screwed

up pieces of paper were placed before the Sergeant. Manny looked at Donny and

grinned, and Donny realised that he was standing with his mouth open.

The Sergeant sent them into a cell, and some woman armed with a bucket of water

and a cloth and another bobby followed them in. She pointed to Donny and the

bobby said, "Stand up son and the matron will sponge down your clothes". He did

as he was told, and he heard Manny start to giggle. The bobby told him to shut

up. The woman started to sponge down his trousers, but in doing so she put her

hands between his legs. He started to pull away from her but the bobby shouted

for him to stand still. Manny was holding himself and tittering away. Jono was

sitting poker-faced but Donny could tell he was laughing too. Donny had never

felt so dirty in his life. She finally told him to sit down and motioned to Jono.

He stood up with legs wide apart, grinning at her. Manny was by this time

helpless with laughter, and Donny was torn between wanting to belt him or belt

the bitch.

The bobby began to get real mad at Manny, "Shut up you dirty little bastard",

and then Manny got mad: he had a thing about being called dirty. He moved

towards the bobby who smacked him in the face and cut his lip. Finally they were

all cleaned up and the bobby told them they would be searched.

The search was carried out in a rough and rude manner, Donny didn't think

anybody could have been submitted to such indignities, but he managed to keep

his cool, he got nods and winks from both Manny and Jono which helped. They were

fingerprinted and photographed and put back in the cell. Manny said, "They must

have had a good night tonight to leave us together." Just then they heard the

most terrifying screaming coming from the next cell. Donny jumped up but Jono

said, "Sit still man", and turning to Manny he said, "Now you know why we have

been put together. They needed the spare cell. Some poor bugger's getting it."

The screaming stopped and a bobby came into the cell and said to Donny, "Hey

you, your Ma's come for you," and led Donny out of the cell.

His mother looked hard at Donny and said, "You're coming home with me now son."

Donny couldn't meet his mother's eyes, he was too embarrassed by the night's

events. His mother signed some papers and they were shown out of the station.

His mother said, "What did they do to you son?" Donny couldn't answer her, and

she didn't press him.

When he got home he pushed past his sister as she opened the door, and ran

upstairs to the safety of his bedroom. He locked the door and threw himself face

down on the bed, where he cried out all his frustration, rage and fear. He

didn't hear his mother or sister knocking at the door.

Donny was standing against the wall with his arms folded and his eyes closed

dreaming his favourite day dream, the sneering face of a copper was at his feet

and he was kicking it.

Ceri Price

(Liverpool 8 Writers'Workshop)

Ceri Price Married mother-of-two. Got most of her education "from being with

people and helping with their problems." Currently writing an Everton-based

thriller.

Tottenham Writers Group

Tottenham Writers' Workshop was started by the local branch of the

Workers' Educational Association two years ago and meets weekly at the Drayton

Community Centre, one of many evening activities for members of the local

community.

The Writers' Workshop gives opportunities to 'ordinary' people to learn from

each other and publish their own writing. Since its inception the workshop has

involved various people with connections in Tottenham. The age range is

considerable and the group shares a wealth of experience from house-wives,

teachers and senior citizens. The majority are women.

Our first major publication 'Slices of Life' reflects this variety. The

anthology consists of short stories, poems and other kinds of writing which are

based on observations made from our experiences.

Mother and Child

The mother built a wall

To protect her child from the world

The child peeped through

And one day broke away.

'Why did you stifle me, stop me from learning?'

The angry silent question from child to mother.

'Four your own good,' the unhappy reply.

The child grew up and built

A wall of silence

To protect the mother

From what she couldn't bear.

'Why don't you talk to me, tell of your life?'

The mother's pain vibrates the silent air.

'For your own good,'the child's unspoken reply.

Sylvia Riley

(Tottenham Writers' Workshop)

The Sisters

'Well whatever you say' she said taking the paperback from her sister.

'It's Woolf's ability to understand human emotions. That's what gets me. It's

the way she translates all that essential alienation into the poetic form.'

Debbie paused for a moment lighting a small brown cigar.

'I suppose so,' Linda said taking a mouthful of lager 'it was just a bit long

winded for me.'

'But then' Debbie smiled 'Literature never was your bag, was it? That reminds me

have you heard that the Women's Action Group are setting up a lit course? You

know all the great plus a few newies. Just up your street. Just the thing for a

beginner.'

'Well it's just the time thing you see.' Linda said.

'I'd do it myself Debbie leaned back in her chair 'But I've got my feminist

meditation class on a Tuesday. That's the thing to get into Lin, whenever it

gets too much just sink inside and forget it all.'

'I suppose so. Have you seen Carol lately?'

'Saw her last week at the nuclear demo. Different bloke. Well let's say new

bloke. No different from all the rest. You know smooth, pseudo type, real ale

drinker. Just like all the rest. Calls himself a socialist.'

'What did he look like?'

'Why should that matter? God Lin you've got to get away from this looks

syndrome. It's not what people look like that counts. It's what they're like in

here that matters.' Debbie pointed to her rib cage. 'Anyway' she said 'He was

just like all the rest except not quite so spotty.'

'Mind you Carol was never short of a man.'

'Yeah, but she gets them all from the same factory. Men this Men that. Christ

and she calls herself a feminist. Never reads anything except her knitting

patterns. She still thinks that The Women's Room' is a place that you go for a

pee.'

'Yes, well I always liked her. That time when I was in trouble and you were away

at university, it was she who helped me out. Kept it all from mum. I don't know

what I've have done.'

'Oh anyone could have done that. It was just a shame that I was knee-deep in my

thesis or I would have come home.'

Linda emptied her bottle into her glass.

'How the hell can you wear those shoes? Don't you worry about deforming your

feet?'

'Oh they're quite comfortable' Linda said tucking her feet under the table.

'And that stuff on your face.' Debbie lifted her arm in the air The money they

make out of people like you, it makes me angry.'

'Well it's just that I look so pale without it.'

'You're just perpetuating an image of women. Just what they want you to do. I

wrote an article for 'Women's Journal' a few months ago on that subject. I'll

fish it out for you.'

'Oh thanks, only what with my studies and everything I don't get much time to

read for pleasure.'

Debbie sat looking at her younger sister and broke into a slow nod, 'Anyway' she

sighed 'How's the nursing going'

'Oh it's hard work' Linda started 'But I like it. There's always so much going

on. It's the dealing with people I like. You meet so many . . . '

'It's that whole set up I don't like. That uniform. They just make you into a

bunch of glorified maids. Not good enough to do anything in the world of real

medicine. Dressed up looking like extras in a porno film.' Debbie stubbed her

cigar out. 'So. Think you'll stick it then?'

'Yes. As I said it can be interesting sometimes. You know sometimes.'

The two girls sat in silence.

'Oh how's that guy you were seeing. You know the one with the sense of humour?'

'Oh him' Debbie looked up 'Laughing himself all the way to his trendy detached

in Upper Putney for all I care.'

Debbie began to dismantle her beer mat. 'Defined by a couple of erogenous zones.

That's our plight. Well I soon gave him the push. Spent weeks unpeeling that

smooth exterior only to find an empty space inside.'

'Well that's a shame. I thought he liked you.'

'Oh he liked me alright. It was his wife who wasn't so keen.'

'Oh.'

'Oh never mind Lin. You've just too innocent for this world. Anyway, how's mum?'

'I think she'd really like to see you. It would do her good. She gets so lonely,

especially when I'm on nights.'

'It's the time. I just don't get the time. I'm so busy with everything. There's

so much to do Lin. We've got to keep on fighting or we'll go under. I'm at

meetings most nights of the week. I mean I've even got one tonight.'

'I know that and so does she. She's proud of you. I heard her talking to Mrs

Cleary the other day saying that her daughter was one of these university

lecturers who was always arguing and fighting for people like her. You remember

Mrs Cleary, mum's old mate from the club. Well her old man's been knocking her

about a bit. Anyway, mum said I'll ask our Debbie, she knows all about that law

stuff. She always talks about you.'

'I know, I know Lin. Look I'm sorry .do you mind if we make a move. I've got to

be at the community centre by eight.'

'It's just that she gets so depressed.'

'Well it's only to be expected. Any woman who has devoted her whole life to

raising her kids is bound to feel a void when they're gone. It's a perfectly

natural reaction. Only the other day I was reading an article on it by Joyce

Green, you know that woman who wrote the piece on menopausal depression' Debbie

looked to Linda for some kind of affirmation, 'Well anyway you should read it

sometime. Look, tell you what, I'll get hold of it and sent it to mum. At least

she'll know then that she's not alone. I mean that's the main thing Lin. When

you're-part of a movement at least you know you're not alone.'

The pub door swung lazily to and fro after the girls had left.

Anne Gebbett

(Tottenham Writers'Workshop)

A Formula for Sleep

Daylight, the thin

dead light of pessimism.

Levels and spreads through the colourless curtains.

The bedroom slowly becomes familiar

Like a polaroid photograph taking shape before one's eyes;

The chemicals of light have brought this room

Into being again. Too soon, too soon.

Put back the clock, please put back the clock,

Stop this unwinding of night into day.

The clock will not stop.

It taps on the scented air monotonously.

Through a crack in the curtains

The sky makes its first choice of the day from a wardrobe of

clouds.

Exiled from the others in this house

I want to reach the country of oblivion before full light.

What spell can I cast?

What formula is there for sleep?

The light switch in the kitchen, with a click,

Restores the blackness of the night outside.

In the children's room two small people sleep

Yet move like broken trees

Floating down a river:

In the morning they will come to rest.

Back in bed I shift and dream uneasily

Until this log body unjams

I break free of the land and reach

The beach of morning in a dreamless sleep.

Ken Worpole

(Tottenham Writers' Workshop)

Burning the Dead Leaves

Light as memories

They lay around us

Uncollected, gossamer-veined

Fragments, rusted away

Dropped at the end of the season

Unfit to plead, these leaves

Unconditionally discharged

Dead.

This year's golden sweepings

Look how they've caught the sun!

Ready for the autumn bonfire

Let's burn them down

In one sweet-scented fire

Burn them down to solidity

And dig them in

Deep as experience

Ken Worpole

(Tottenham Writers' Workshop)

Shahida

(from a long time ago)

Shahida entered our life in the middle of a music lesson. We had been acting in

our usual manner, and Miss Mankovitch was acting in hers, the combination of

which would result in one more teacher having a breakdown.

Recorders in mouth we continued blowing, a strange and horrid sound above Miss

Mankovitch's hysterical pleas to 'STOP ....... STOP :......' which we took as

the sign to continue.

Only Miss Tibbs visitation could have stopped us, which it did. Miss Tibbs was a

force above all human experience. We all stumbled to our feet with trembling

eyes at this stiff holy figure. She walked over to the transfixed Miss

Mankovitch with Shahida trailing at her side.

It was only after Miss Tibbs left the room that comments about this new girl's

appearance came tumbling forth. This was someone indeed different to us. Her

black heavily oiled hair was pulled severely back in a long plait, revealing

glittering stones in her dark ears, and under her gym slip hung long silk

pyjamas. She cut a sharp contrast to us, too sophisticated for gym slips in our

navy skirts, and our sometimes successful attempt at boufonting our hair. I knew

before it happened that Shahida would be sat next to me, Pauline my best friend

was away ill, and well ... I just knew it.

She had to share my book to sing Nymphs and Shepherds. Shahida wasn't to know

that no-one ever really sung, it was left to Miss Mankovitch to enthusiastically

pound the piano and sing, while we passed round notes and sweets, giggled,

opened our mouths up and down a bit, and occasionally might join in the chorus.

Shahida actually sung. I felt embarrased for her, but when she sung 'In tis

grove, instead of 'In this grove I felt angry with her, for a start she

was enjoying singing such a crummy song, and she couldn't even get it right. Yet

when I saw the other girls nudging and laughing at her, I felt so sorry for her.

Shahida was unlike us, she was .... well .... innocent.

Shahida followed me around like she was my pet puppy, and my feelings about this

were very mixed. I resented her tagging around me she seemed to highlight the

fact that I too was different from the other girls. I didn't want to be isolated

like her. Yet she was company for me, she fascinated me in a way, her life was

so different from mine. Yet she also annoyed me, surely she realised that by

always giving her homework in on time, and wearing the babyish school uniform

she wore she set herself apart.

She actually talked about school work, which was of course a taboo subject.

Everyone else talked about boys, films, music, clothes or hairstyles. One

evening after the bell had gone I went into the cloakroom to see Shahida in the

middle of a group of girls. Shirley and Carol were doing most of the talking.

Everyone else in the class looked up to these two and tried to be like them.

Have you started yet, they said to her.....

Shahida didn't answer.

But she doesn't know what we are talking about ... do you Shahida?

Still no answer from Shahida.

What do you know Shahida, how do babies come?

Other voices joined in to taunt her, girls were laughing and seemed to be

closing in on her.

Shahida never played P.E. like us, and therefore we had never seen her in the

navy knickers and blue tea shirts we all were exposed to.

What's wrong with you, why can't you get undressed, why are you so different

from us?

One girl pulled up her gym slip to reveal the full length of her silk pyjamas.

Shahida looked terrified, she looked at me. I knew I should have shouted at them

to stop it or call someone, but instead I grabbed my beret and raincoat and ran

as fast as I could away from the school.

The next day Shahida didn't come to school. Miss Sidebotham, the deputy head,

told us in a very severe manner, that Shahida would not be coming back, and that

we should all be ashamed of ourselves. I am sure many of the girls were, because

none of us ever mentioned Shahida again.

I didn't even mention the incident to my mother. My mum was always doing battle

with everyone, the milkman, provident man, stall holders. We were Jewish and she

was always going on about:

'leaving others alone it wasn't that long ago that we came over on the orange

boats'.

No, I certainly couldn't have told my mother. She would have demanded to know

what I did about it, and I would have had to explain that I did nothing when

Shahida needed me most. And you see, if I was being honest it wasn't just

because I was scared of the others. I have to admit it in some ways I was glad

they picked on Shahida, because when they started on Shahida they left me alone.

Laureen Mickey

(Tottenham Writers' Workshop)

Nursing Home

The old women

in the nursing

home wear

tarnished wedding

rings,

hysterectomy scars

and floral nighties.

They have been

the carers

the givers

the lovers

for most of their lives.

Until their babies

had grown,

their husbands

had died,

their bodies

had aged

and surrendered

to exhaustion.

They are left

by loved ones

to be cared for

by strangers.

Jean Rhodes

(Tottenham Writers' Workshop)

New Song for an Old

Dead

The Woodhead road was yellowjack

blown in with the rain,

The Woodhead road was tommy-shops

gouging us for gain.

We knew the bitterness of death

from bitterness in life.

Angels in a digging hell

past hope of paradise,

We're headed for the Yorkshire side

of somewhere deep below

Infernos we've accomplished,

devils that we know.

The loud militia held us to

our contract with the line.

How many miles to heavens gate

Serving Old Nicks time?

Ours that wrenching railway

from hand and sweat and gut,

The makers and the murderings

in Godley churchyard shut.

Joe Smythe

(Commonword, Manchester)

Matchless

There was no other way out. He knew now, whatever he did or thought no longer

mattered. Try as he may, he would never get away. He was surrounded, all doors

closed. And milling around him were humans all in the same terrible situation!

It was hopeless. He shivered. He would be too late! He clenched his teeth, to

stop his anger and anxiety. No use. In a couple of hours it would be all over.

Even in the cold building he sweated. Perhaps one more try? At last, with one

superhuman effort he was free! The great doors slid open.

He ran the rest of the way, hands wet with sweat, keys slipping from his hands.

Cursing, he snatched them up. Then, bursting into the flat door, shedding his

clothes as he went, he shouted, "Is the match over? That bloody lift jammed

again!"

Mrs. M. Pendragon.

(Harlow, Essex)

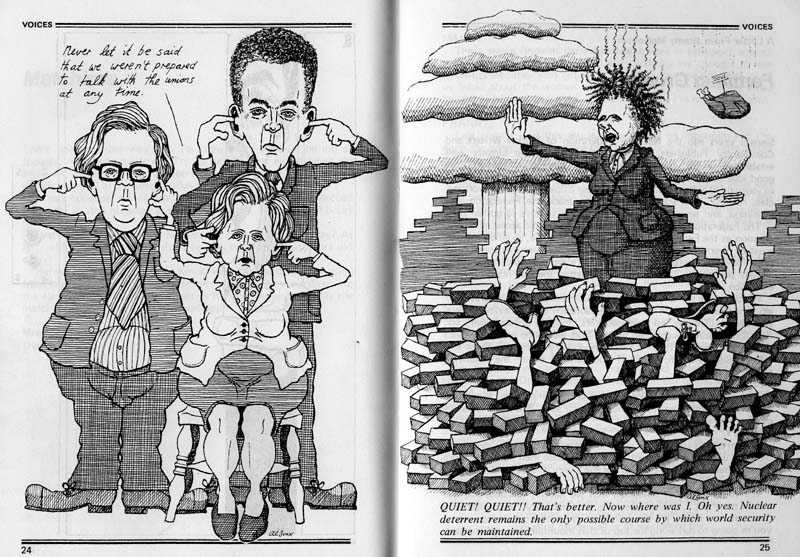

A Letter From Jimmy McGovern

Feminist Groups

Several years ago the National Federation of Worker Writers and Community

Publishers was formed because some already well established, viable

working-class writers' workshops thought it a good idea at the time. The history

is well documented; you'll find it in journals like New Statesman and New

Society typical working-class reading. The workshops, you see, made the

Federation, not vice-versa, and some of our comrades seem to have forgotten

that.

The Federation exists to give working-class people access to media. As soon as

the Federation fails to do this it will die, so all our efforts must be directed

at this fundamental task. Therefore we cannot cater for middle-class writers

because: 1) there are thousands of journals already doing this; 2) to do so

would destroy the very reason for our existence.

Which brings me to Feminist groups. A few years ago a handful of working-class

women in Netherley established the Netherley Writers' Workshop. (They've no paid

workers; they're unsubsidised, but they'll be around longer than most). That

workshop was the subject of a report on page 18 of the November 1979 edition of

Spare Rib (an excellent edition; get it if you can) in which the following

appears:

OLIVE:

About your magazine, Spare Rib. I get the impression that those women are

writing with their heads in the sand. They're not aware of what we're living.

FRANNY:

I've often thought, how many of those women have ever been married, or divorced,

and got any kids. Because then they'd be more down-to-earth people. I think

Spare Ribs very middle-class.

MARIA:

It's about a sort of liberation that we haven't reached, and will maybe never

get.... like "liberating your sexuality". Although we'd like that very much,

it's like saying to us: you've got no legs now you're going to run along the

top of that mountain. It's still abstract.

MARIA:

There was a Reclaim the Night March here in Liverpool, against men hassling

women, but from the publicity we thought it was against prostitutes. This girl

we knew who'd been on the game asked us, what about the women who are going out

tonight to get shoes for the kids? And I thought, oh well, frig that, I'm not

going marching to stop their business.

FRANNY:

Last night I read this article in Spare Rib on lesbianism and I'm none the

wiser. It's just these bloody big words that go right across the page.

HELEN:

And that's another way of making a working-class woman feel even worse. She's

already feeling frustrated, she knows that she hasn't had the best education,

and then she picks something up supposed to be about her oppression 'and

it's written so that she can't understand it.

OLIVE:

So for Christ's sake, Franny, you've got to write something for women from your

class (my emphasis) and of your sexuality ....

Obviously there's a deep mistrust, in the above, of the Feminist movement and

the apparently middle-class women in it. Therefore to admit Feminists per se is

to risk alienating people like Maria, Franny and Olive, genuine working-class

women, vital to the Federation. In any case, there already exist several

journals for women committed to feminism; the Federation should concern itself

with the issues Fran, Olive, Maria and Helen raise issues of sex and class.

Incidentally, in the light of Franny's and Helen's final words above, would

VOICES readers believe that at our recent Nottingham A.G.M. about one hour of a

very well attended workshop was given over to a discussion of Lord Byron and

heroic poetry? Several well-spoken people paraded their wide reading .....

Anyway: if, by admitting Feminists in general rather

than specifically working-class feminists such as the women from Netherley we

undermine our movement, why do we do it? Well first, it has been said that our

constitution demands it. This, in fact, is incorrect: nowhere in the

constitution is there a mention of feminist groups and clause 3 of the

constitution seems actually to debar them By 'working class writing' we mean

writing produced within the working class and Socialist movement or in support

of the aims of working-class activity and self-expression. (Agreed constitution

of A.G.M. 1978 distributed Hulme Library 1979. Also reproduced in recent VOICES

editions).

But second, there is the undeniably irresistible appeal of "unity", a unity of

oppressed groups everywhere, and many Federation members see the worker-writer

movement as this sort of political weapon.

Now, this is worth looking at. Take the feminist movement, for example. It

undoubtedly is, has been for some time, and probably always will be, a major

political force superficially a fine addition to the worker-writer ranks. But

feminists would view the Federation as only a second or third string to their

bow (excuse sexist metaphors), their primary concern being feminism. And it is

precisely because feminism has been their primary concern, it is precisely

because they have been so exclusive in their movement (viewing men with

justified suspicion, "positive discrimination" in Spare Rib) that their movement

has become so strong. So to all comrades who see the Federation as a political

weapon I'd say: learn from the feminists, keep the movement exclusive; ban all

non-working class groups and so ensure that we have the necessary sense of

direction, the necessary common purpose, to use the resultant political clout.

Finally, this piece has discussed non-working-class groups. Non-working-class

individuals have been invaluable to the Federation and of course they should

stay within our ranks as long as they recognise the Federation for what it is:

a Federation of working class writers and publishers.

Jimmy McGovern

(Scotland Road, Liverpool).

Women and Words

Women and Words, the Birmingham Writers' Workshop, was started as a WEA

class by two of us who wrote ourselves and wanted to share our writing because

we were sick of hiding it and feeling stupid and embarrassed about doing it. We

believed that other women had the same experience. The decision to make it an

all women's group was assumed it followed from our belief that there are

things (including writing, no matter what the subject of it) which we need to

discuss, initially, in a space apart from men. We took a more conscious decision

to make the group a locally based one, rather than setting up meetings in

central Birmingham which would be accessible mainly to women with cars and the

means to travel.

We began, in January 1980, with a pub reading by writers from the Netherley and

Bristol Broadsides groups, and our first session attracted women of all ages and

of a wide range of jobs, politics and experience. One of the most exciting

moments was sitting in that first meeting, in the community room of a local

school, listening to the other writers talking, all for the first time, about

the fact that they did write, about how they'd never shown their writing to

anyone, and about what a big step it had been for them to come to the workshop.

Since then we have met every week. We began to be asked for contributions to

local papers and to the WEA Women's Studies Newsletter We have given readings

at women and children's groups in the area, and in pubs; and in November 1980

we published a selection of our writing in a book called "Don't Come Looking

Here". We now have between thirty and forty women from all over Birmingham who

are interested in the group, and between 8 and 12 who come regularly, some of

them having to cross town on two buses to get to us.

We applied fairly early on to join the Federation, seeing it as being about

helping to give access to writing and publishing to groups in society who are

generally barred from those areas, and about breaking down the notion that a

writer has to be a solitary genius with a mystical gift. We wanted to be in

contact with other groups who were also trying to write and publish their

writing, and we felt that that contact would help us, not only in our immediate

aim of becoming more powerful and courageous in our writing, but also in the

more long-term one, of trying to reach other women in Birmingham who haven't

been able to get to the present group though they do write. Some of our original

members have had to stop coming because of pressure of work, or because of

problems over childcare or transport. Other women we've met when we have done

readings have said that they did write but couldn't get away in the evenings,

and so we have formed a day time group with a crθche, and some of us who live in

other areas are thinking about starting workshops nearer home.

We feel very strongly that Women and Words has made a difference in our lives

through the confidence that has come from speaking out about our writing, from

the pleasure we've got from writing more and having an interested audience for

our work, and because it's been a space for us away from the demands of work and

family. And we believe that that kind of possibility should be open to everyone

who wants it.

Once Upon a Time

Once we would enter without knocking

Come together without a greeting

On parting not need goodbye

That was once.

Now, we observe the conventions of social intercourse.

You say you are changing cities

And will be only a train time away.

"That will be nice," I say.

Please don't misunderstand.

No regrets for the space that shimmers between us now

Oh, I realise everything changes

Strange friends into friendly strangers.

But after all the permutations

The juxtaposition of relations

Wearied years of trying hopeful (or hopeless) combinations

Never again have I been anywhere close

To the way we lived, you and I, once.

Cath Gilliver

(Women and Words, Birmingham)

Virgil's Enid

Have you ever wondered

What Enid was doing when

Virgil was churning his sagas out?

While he was vicariously living out

Heroic battles on alien soils

And wending his way across

Mountainous seas.

What was she doing then?

While he cavorted with Dido

In the equatorial sunset,

and was alternately Boy, Lover, Warrior MAN?

What satisfaction did she get?

The satisfaction of knowing she

was stoking the genius' furnace?

The smug, cream-lapping comfort of

being the power

Behind the throne.

Content to nurture another's amibtions

To furnish the stuff that dreams are made of

To be alternately supplier, support, supplicant

SAINT?

While Virgil was keeping the lads on tenterhooks

About the fate of the 'J.R.'s' of his day

And in between hoisting a few jugs of ambrosia,

Did something in her stir?

And did she go to the bureau

And take out pen and ink

Or rescue a piece of charcoal from the grate

And scrawl the very first graffiti on the kitchen wall!

"NO MORE VIGILS FOR VIRGILS!

ENID WAS HERE!"

Sue Learwood (Women and Words)

Don't Come Looking Here

Don't come looking here

For strong words

Or images to pull you through or shore you up.

Don't come looking here.

This is one of those end of the line,

Face in the gutter,

No more for no-one, nowhere poems.

It's about defeats,

Not victories,

About weaknesses,

Not strengths.

About fear,

Not courage.

It's a finished, washed-up, strung out poem.

It's a poem about what men do to women

And what women do to themselves.

But it isn't the only poem

And it doesn't come last,

It comes first.

Rebecca O'Rourke (Women and Words)

Haiku

My daughter glances up.

I fall back through her eyes

into my childhood.

Sylivia Winchester (Women and Words)

Michael's Story (part two)

The following morning, John took his brother, Michael, out with him to

the job on which he worked, which was making a branch railway line from Park

Royal to Ruislip. It was rough, dirty, slaving work, but it was better than no

work, or so those who worked there thought.

In those days, civil engineering contractors chose their gangermen and walking

gangermen they whipped up the gangermen with great care. Only those who

looked like scoundrels and behaved like bullies were considered. Anyone with

even a speck of human compassion in his make-up had no need to apply for the

job, for even if he got it, he wouldn't last long.

The contractors on this Job were Wimpey & Co., and the ganger-man under whom

John worked was known affectionately as The Dog' Brennan. He was called numerous

names as well, such as the 'Screech', the 'Shout', the 'Mouth', and a host of

other less complimentary ones. But he liked being called The Dog', for he

thought that boosted his reputation with the contractors and made him sound more

frightful to his workmen.

"This is the 'Screech' now, "John whispered to his brother as a burly man with a

huge, blue-red face ambled towards the knot of talking, jesting men who stood

waiting for him. As soon as he appeared in sight, all jesting and talking

stopped, and everyone looked a bit awestruck.

To Michael the man looked fearsome. He wore the typical ganger-man's uniform:

moleskin trousers, hobnailed boots, a black cardigan underneath a heavy, black

jacket, a black shirt, a black scarf tied in the usual round knot and the ends

cast over one shoulder and a greasy cap slung on the side of his head. He rolled

so much when he walked that often he looked as if he was going to topple over,

and the outward swing of his free hand the other was always tucked down in his

trousers pocket appeared often as a guard against the fall.

"Right, blow up!" he roared before he came nearer than ten yards to the knot of

workmen, and his voice was hoarse and rumbled with deliberately cultivated

ignorance.

Michael momentarily jumped with fright and slid behind his brother.

Scarcely had the scream of the gangerman died down when every workman except

John was scurrying for the toolshed, which the gangerman had unlocked. John

waited behind, but he appeared a bit uneasy.

"This is the young fellow, just come over, no cards or anything, think you could

start him?" he asked tremulously. Just perceptibly the gangerman nodded, and

John waited for no other sign, but scurried to the toolshed as the others had

done.

"Hello," Michael greeted, but the gangerman didn't reply. If anything, his scowl

deepened. Then he said out of the corner of his mouth:

"Wait here 'til I put these men to work," and he rolled away after the hurrying

men, one arm swinging straight out from his body, the other thrust deep into his

pocket, his shoulders hunched and his head switching from side to side in the

manner of a Stpnewall Jackson.

More than an hour went by before the gangerman appeared on the horizon, and

during that time, Michael allowed his thoughts to run loose.

"He looks like Old Nick," he remarked. "Jesus, I bet he drives men something

shocking. They all seem afraid of him, anyway. Ah, but sure, if a man does his

work, what can he do? And I'll do my work, no doubt about that. I will that. By

Jese, I'll stick it so how bad he is," and with these thoughts Michael consoled

himself until the gangerman was quite close. Then he turned all attention to the

man and listened very carefully to everything he said.

"So, you have no cards, have you?"

"N.n.no," replied Michael. "Sure, I can't play anyway, only snap."

The gangerman turned away in disgust and scratched his head.

"Hee, hee! you bloody goberloo!" he bellowed. "Hi! do you want a start, or don't

you?"

"Oh, Jesus, aye, 'course," replied Michael enthusiastically.

"Well, then, you want a set of cards, don't you? Insurance, hah?"

Michael nodded indecisively.

"Never mind, I'll get you fixed up. Eh, I don't know, what I do for you 'greesheens'!

Come on!"

Michael followed the gangerman who had started walking in the direction from

which he had come that morning.

"Now, I'll get you fixed up with a set of cards, I will, then, now, well, ah!

The rest'll be up to you, won't it? Won't it?" he asked a bit more aggressively

over his shoulder.

"Oh, aye, fair enough, fair enough, sound, sound!" agreed Michael as he hurried

along behind.

"Never mind that friggin 'greesheen' talk," admonished the ganger-man. "Smarten

yoursel' up a bit. You're here now, not driving neddy to the bog. Come on!"

When they arrived at two small, green huts that nestled against a huge

embankment, the gangerman knocked boldly on a square, green-shuttered window.

Almost immediately the shutter slid up and a young voice asked from inside:

"Yes? Hello? Oh, hello Mac, what can I do you for?"

The gangerman stroked his chin and asked politely: "I wonder if you'd do

something for me?"

" 'Course, anything, what is it?"

Still stroking his chin, the gangerman continued apologetically: "Well, now,

see, I have a joker here with me an' he's just docked. I'd, like to start him,

but he has no cards. Think you could write a letter that he could give to the

labour exchange and get some?"

"Me, 'course!"

"Oh, good man, good man."

"No trouble, where is he?"

"He's here. Hi! Come up here, you bogdale stump! Jesus, I'm all right with a set

of grogeen-builders like you lot, I am. Up here! Talk to that man there. He'll

show you how to go about getting a set, a set of cards. Phew!"

"Yes, good man, sound, "Michael replied as he hurried to the window.

"Name?" the clerk asked with poised ballpoint."

"Who?"

"Who! Who what?"

"Ah, I don't know who you're talking about at all."

"What's your name?" the clerk emphasised, "your full name? N.A.M.E."

"Oh! Oh, Michael McWanted, yes, Michael McWanted, ummm!"

"Yes, Michael McWanted," the clerk repeated as he wrote. "Yes, address? Hi,

'Mac! Haven't we a McWanted working here? Isn't there one on your section?"

"Aye, me brother," replied Michael with a definite ring of pride in his voice.

"He's me oldest brother, that one, he is, indeed."

"Oh, now, indeed, he's there," sneered the gangerman, "but for how long, now!

I'm going to do a bit of weeding one of these days. Just the right weather, too,

for a bit of weeding. Well, that's how you get a good crop of turnips, so they

tell me - thinning 'em out," and he laughed vindictively and shook his head. "Ara,

great crack altogether!"

The clerk smiled knowingly and shook his head slowly before continuing with

Michael. "Address?" he asked a second time. Michael hesitated.

"Where do you live?"

"With me brother."

The clerk flung his pen down on the table. "Where?" he demanded impatiently.

"In London, here."

The clerk walked away from the window, then laughed loudly at the ludicrousness

of the reply and the silly posture of Michael, who stood with his mouth open,

not knowing what was happening. When the clerk had overcome his bout of

laughter, he tried again. "No, I mean where do you live. What's the name of the

street you live in, and what's the area?"

By this time Michael was totally confused. "Jesus, I don't know the name of it

at all, but it's not far from the pub. You turn up to the right. It's a short

street. Mind you, it's not all that short, but it's shorter than the long ones."

Again the clerk burst out laughing, while the gangerman looked savagly from

under his obliquely hanging cap. Then he walked to the window, roughly pushed

Michael out of the way and said to the clerk:

"Ara, put any address at all down. What does it matter? Sure he won't be here

all that long anyway. Put anything down," and he turned away sharply.

"Okay, replied the clerk, picking up his notebook and retiring to the interior

of the little hut that was being used as an office.

In a few minutes he was back and handed Michael a sealed envelope. "Now, you

take this to the labour exchange," he explained "you hand it in there and

they'll provide you with a set of employment cards. Okay?"

"Yea, okay, great, thanks," said Michael, as he took the envelope and turned it

over a few times in his hand.

The clerk slid the shutter into position once more, but Michael remained

standing there, looking once down at the envelope, then up to the

green-shuttered window and uncertain of what to do.

The gangerman watched him with a look of evil amusement on his blotchy,

beer-reddened face. "What are you going to do with that now?" he barked, hoping

thereby to increase the lad's trepidation.

Michael thought, then held out the form in his trembling hand. "Give it to you,"

he suggested.

"Awoo-woo!" screamed the gangerman, stomping away from the lad. "What in the

frigging hell do I want it for? To wipe my frigging kuyber with it? See, I have

my cards, so I'm all right. I've not just left the hob, you know. You as wants

frigging cards." He walked back to the lad again and with the index finger of

his right hand began to draw imaginary diagrams on the half-open palm of his

left hand. "See, here. Now listen, you take that thing there to the labour

exchange, give it to them there, and they'll give you a set of cards.

Got that?"

Michael nodded, but looked more disconcertedly at the envelope.

"Know where the labour exchange is?"

"No," replied Michael, now completely rattled, for events of the past hour or

two had not only frayed but scalloped the outer edges of his earlier illusions

about England and the Irish and life in general.

"Boo-hoo!" snorted the gangerman, puffing out his beer-bloated cheeks in feigned

agony. "Well, I'm all bloody right here, I am" Then he spied a lorry standing in

the nearby yard with the driver sitting comfortably in the cab.

"Hi! Mac!" he called to the driver.

"You what, mite?"

"Will you be going anywhere near the labour exchange today . . .

soon, hah?"

"Yes, going right past it now, why?"

The gangerman rolled towards the lorry and spoke to the driver in a quiet,

sweetly-toned manner. "Oh, good man, good man. Think you could do me a favour,

hah?"

"Yea, certainly, anything, what?"

The gangerman stroked his face as if hesitant to ask. "Well, you see, I've a

joker here I'd like to start, but he has no cards. Think you could drop him near

the labour exchange so that he can get some,

eh?"

"Yea, certainly, mite, why not. Without stopping, if you like,"

and the driver laughed peevishly.

The gangerman also grinned and showed his nicotine-stained front teeth. "Oh,

now, well, indeed you could do worse, you could."

"Okay, where is he?"

"Here. Hi! Come up here, you heydog, you."

Michael hurried over to the lorry.

"Now," began the gangerman in his usually hoarse, biting voice, "this man'll

take you near the labour exchange and drop you off there - head first, I hope -

and give them that form and they'll give you cards. Think you can remember all

that?"

"Yea, 'course, great, sound," Michael replied with obvious relief.

"Well, jump in, then. He's not going to wait all day for you. Jump.. . I"

Michael's actions had become so erratic and disordered that he gave a

mighty

jump, cracked his head on the top of the cab door and nearly knocked himself

unconscious. Both the driver and the gangerman laughed heartily at his

discomfiture.

"Straight from Mary Horan's, is he?" asked the driver sarcastically.

"Oh, now, where else. By Jesus, she keeps dropping them and shipping them

across. And everyone's worse than the one before. Eh, I dunno!"

"Starting for you, is he, Mac?"

"Starting, oh, aye, he's starting. I'll have him, but as McGreever said; 'I

won't keep him long! Now, see, you lahwohle! Be out here first thing tomorrow

morning, and grease them elbows of yours tonight, for by Jesus, you'll need to

have them greased, 'cause I'm going to knock some work out of you, or knock some

savvy into you, I am that."

The driver laughed again, waved good bye to the gangerman who didn't bother to

return the gesture engaged the gears and let the lorry slide forward.

The gangerman rolled back to his own section of work. "Jesus, this is great work

altogether," he told himself. "Jesus, a man can have a great crack with these

lachikoos that are coming over now, ha, ha!" and he hurried his steps to bring

him more quickly to the core of his section of work, the work he loved, the work

that transformed his inferiority complex to a superiority one, by affording him

an opportunity to make people squirm before him, and he vowed as he walked along

that before that day was out he would make a few more squirm, make a few more

realize who was king and who had the power in that area of life's activity. The

thought titivated his sadistic nature, and the imbecilic smile of a drunken man

creased his beer-blown face. He spat out a load of catarrhal phlegm, settled his

cap at a more rakish angle and exaggerated his roll even more as he headed for

his own midden.

The driver of the lorry and Michael didn't communicate until the lorry screeched

to a stop.

"There it is, mite," said the driver, leaning over Michael's knees and pointing

to a big building that stood a few yards back from the pavement. "That's the

entrance, there, see."

"Oh, good man, ta, thank you very much," said Michael as he prepared to get out.

"First job is it, this?" asked the driver.

"Yes, first job. I only came here yesterday. Me brother works for this man."

"Yea, well, best of luck, Paddy."

"Sure Michael's my name."

"Yea, well, best of luck anyway, mite. Tra!"

"Oh, tra! Thanks a lot." Michael jumped down from the cab "Thanks....."

But before he could finish the lorry lurched forward and was soon out of sight.

Michael had no trouble at the exchange. A young lad dealt with him, at first,

then an older man came along. After smiling amiably, he sat on a seat on the

other side of the counter, right opposite Michael and began to write. "Sign your

name there, he said eventually to Michael, turning a sheaf of papers round and

indicating with his index finger where he wanted Michael to append his name.

"Yes, that's all right," he said after examining Michael's signature. "Now you

want a green card. Oh no you don't. It's not green-card work, that. You just

want employment cards. Okay." He took a buff-coloured document from a drawer on

his right, copied into it from the sheaf of papers in front of him, then threw

the buff thing to Michael. "There you are, those are your employment cards. Good

day."

"Oh, thanks, thanks a lot, smashing, great, soun . . . . " But the man had

vanished before Michael could conclude his appreciative remarks.

Michael put the cards in his pocket and walked out. A warm ray of happiness

raced through him. He was in England, had lodgings, a job and was with his

eldest brother. What more could he want? He started whistling, but stopped

abruptly when he remembered his brother's admonitions, and walked along the

street with his head down.

Time dragged terribly as Michael moped along aimlessly, looking into shop

windows, reading advertisements and always making sure that he didn't roam too

far, just in case he found difficulty in returning to the digs. By the side of

the road, he saw a wooden seat and he eased himself on to it and allowed his

thoughts to wander aimlessly to County Mayo.

"Jesus, I'm lucky," he said to himself. "I have a job now and everything. Jesus,

I'll be able to send the old fellow and the old girl a few quid soon, maybe next

week," and he rubbed the palms of his hands together with glee. "Jesus, I wonder

what they'll say when the money drops out. Hah?"

He began to imitate his overweighted, stiff-backed mother reaching for a letter,

laboriously opening it, seeing the money fall to the ground, shouting anxiously

and excitedly as it did so, then stooping slowly and painfully to pick it up.

"By Jesus, I told you he'd make the best man of the lot, didn't I?" he said in

the rough squeaky voice of his father.

"You did, he is," replied the mother. "By Jese, he'll show the other scuts up,

he will, hah?" He nodded heavily as he thought his mother would do. Again he

rubbed his palms together vigorously.

The sharp bark of a dog roused him from his soliloquy. When he looked round, a

man was standing a few feet away with a very puzzled look on his face.

"Awright, mite?" the man asked. "Aw . . . Yea, yes, yes, great, sound," Michael

returned. "Great, sound," repeated the man as he began to walk past. "You didn't

sound so great to me. Sounded like you were ready for the skin suit. Could De

Valera not find you a job over there?" "No, now, no job," returned the ingenuous

Michael. "No, we have to, though. I know what I'd do with you," and he walked

off, whistling up his dog as he went along.

By mid-day Michael was very hungry, but he thought he dare not go to the digs

before his brother came home from work. He had nearly a pound in his pocket, so

he decided to look for something to eat. Several times he passed a small cafe

before deciding to go in. At last he ventured in.

"A cup of tea and a currant bun," he ordered from the man

behind the counter.

"You what, mite?" the man remarked. "You've go' a curly bum?" "No," Michael

explained as best he could, "a bun with currents

in it."

"Goh, blimey!" scoffed the cafe proprietor. "Go' above!

Well, I've heard of 'em wi' buttons on, but never wi' currants in 'til now. Gooo!

They don't come any better, do they?"

Michael stood for a few minutes aghast, for he hadn't a clue what the cafe owner

meant. Then, as the man made no attempt to serve him, but just kept on laughing

more and more hysterically, Michael walked out and decided to wait and have

dinner with his brother.

He waited near the bottom of the street in which the digs were situated until he

saw his brother coming towards him. Then he walked forward impetuously and showed

his brother the buff cards in the inside pocket of his jacket. He was smiling

happily. "Right now, amn't I?"

John nodded as they walked side by side towards the digs.

"How did you get on with the 'Shout' out there?"

"The gangerman? Oh, Jese, he was great, sound, great."

"That's good."

"Oh, he was, damn me, sound."

"Now, don't forget," John warned, "take off those boots before you go upstairs,

or that old witch'll jab herself up the arse with her broomstick."

"Take 'em off downstairs?"

"Yes, that's it."

"And walk up in bare feet?"

"Yes. No, you keep your socks on."

"Jesus, it's awful."

"Yes. Now, just do as you're expected to do and leave it at that. Right?"

"Oh, right, right, sound."

After having had a good wash and having changed into clean clothes, John and his

brother came down to the kitchen, where the landlady had a cooked meal on the

table.

"By heck, tell you one thing," commented Michael.

"What's that?"

"This old girl knows how to feed a man. Jesus, you can tell she's Irish by the

feed she puts before a man. Jesus, she knows how to feed a man."

"You what?" asked his brother.

"She gives a man a good dinner, anyway, whatever about a supper."

"She gives a good dinner! Sure that old hag wouldn't give a man the toothache.

She may give a man the hiccups looking at her. Gives a man . . . . . Sure, isn't

it I buys all the grub. All she does is cooks

it." He examined some slices of cooked lamb on his plate." Or half cooks it. Tct,

tct, tct!"

When they had finished eating, Michael said gleefully: "Well, this time tomorrow

night, I'll have earned my first day's wages in this man's country," and he

stretched and smiled to himself.

John smiled back, but made no comment.

A few minutes later the landlady poked her long face round the door jamb and

yelled: "Now then, you two! This is a lodging house, not the House of Commons,"

and with that she switched off the light "Stay yacketin' there, you would, worse

than a crowd of crows. Must think no one pays for light in this house. Come on."

John and Michael groped their way upstairs.

Michael lay on the bed, looking at the ceiling and thinking, while his brother

began getting ready to go out.

"Are you not getting ready to go out?" he asked Michael eventually.

"No, out where?" enquired Michael.

"Out where! Well, the pub is the only place I know of."

"Jesus, sure a man can't go to the pub every night, hah?"

"Well, it's either that or going to bed, 'cause keep-death-off-the-roads

downstairs'll put those lights out now any minute. Come on, or you'll be groping

about in the dark. Get up."

"Jesus, sure a man'll save nothing if he goes to the pub every night."

"Hi! never mind now about that, come on, get ready."

Michael yawned and stretched lazily, but a frantic screech from downstairs

brought him suddenly to his feet beside the bed.

"Hi! you two up there! These lights are going out any minute, so make up your

minds. Are you going out or going to bed? I can't afford to have lights going

all night just to amuse you two. Hi!"

"Sorry missus, won't be a minute, missus, just getting ready, missus." John

replied. "Hi! Will you for Christ's sake hurry."

"You can have another minute and then that's it," came the landlady's final

warning.

"Right, missus, we're nearly ready now. Come on, hurry."

Michael quickly brushed his hair, slipped on a pullover and jacket and followed

his brother downstairs and out on to the street.

"Jesus, this is awful," he remarked to John as they walked side by side towards

the public house. "Are all landladies like that?"

"No, some're worse," remarked John offhandedly.

"Ara, Jesus, how could they be worse?"

"Well ..... ah, never mind. You'll find out before you're here very much

longer."

"Find out what?"

"You'll find out that the only time a landlady wants to see you is Friday night,

when you're giving her the shillings. Then she doesn't want to see you again

'til the next Friday night. And they're all the same, Irish, Scotch, English, no

difference, all the same."

"Jesus, you know, a man'd be a lot better off in a bit of an old room," Michael

suggested.

"A room?" His brother pondered that suggestion. "Tell you what, with two of us

living together and sharing the one bed, we just could be better off in a room."

" 'Course we would," Michael waxed enthusiastically. "Sure, if a man had an old

room, he could sit in by the fire at night and read an old paper, or something,

instead of going out every night drinking. Jesus, I hate that old caper

drinking every night."

John had been watching his brother sternly, but didn't interrupt him. When he

had finished, John reminded him hotly. "See, you're in England now, and the

sooner you forget all those old tales you've been told, the better it'll be for

yourself. Jesus, you'll have everyone laughing at you if you keep on like that.

Sure, whether you're in digs or in a room, no one'll let you keep a light on all

night, these days. Sure, no one can afford to burn lights all night, these days.

Sure, no one has any money these days, what are you talking about?"

"Has she no money, the old hag we're digging with?"

"Money! Well, not enough to open a shithouse door. Ara, where would she get it?"

"A shit...?".

"Money! Sure her husband isn't working at all. Sure all she has is the miserable

bit she makes out of keeping lodgers."

"Haa, but I bet that's a tidy old slice, too, hah?"

"Nothing! Nothing hardly. Sure those poor devils are just like ourselves

scraping along best way they can."

"Jesus, you know, I never thought things were like this in this country."

"Well, no you wouldn't listening to all the tales they tell over there. Sure,

don't they sing songs there about picking money up on the streets here. By

Christ, then, they have a big shock when they come here. They soon find out that

there's not much money on the streets here, not even when you're digging the

streets up."

By this time they had arrived at the public house, and as John was pushing open

the swing door, Michael announced:

"Jesus, I don't think I'll have any old beer tonight."

John allowed the door to swing back into position again.

"What are you going to have, then?"

"Ara, Jesus, I don't think I'll have anything. I think I'll just sit there,

that's all."

"Now, get this straight," his brother began earnestly," no landlord is going to

allow anyone to doss in his pub. You either drink beer, or something else, or

you get out. Anyway, you're living here now, and you have to live the way you

have to live, that's all. So, forget all the ideas you came here with, or what

people over there told you. You're here and you have to live same as everyone

else," and with those remarks, John vigorously pushed the swing door open,

walked in, looked all round, them stomped to the bar. "Two pints of Walker's

Main Line," he ordered from the barman who merely nodded in recognition, no

more.

"We'll sit over there," he said to Michael and pointed to an empty space on a

wall seat between two tables, around each of which sat men playing dominos.

Having paid the barman, John picked up his glass and beckoned with his head to

his brother to do likewise.

Michael picked his glass up and followed. They sat between the tables and nobody

spoke to them, and they spoke to no one either.

Michael sipped from his glass and pulled his face as if he had tasted gall, but

his brother drank as if he liked the stuff, then placed his glass on the floor

near him.

"Jesus, you don't like this stuff, do you?" asked Michael.

John lifted his glass up to the light, inspected it carefully and asked in turn:

"Why not? It's all right, isn't it? I think it's the best of the beers around

here."

"No, I don't mean that," asserted Michael. "I mean, do you like drinkin' beer? I

hate this old caper drinking beer every night. Ach! No good to no man."

"Hee, hee, you've something to learn," his brother scoffed. "When you're not

able to buy a pint, that's when you'll worry."

"Me? No, I won't worry. I wouldn't care if I never saw a drop of the stuff. God

above, it's awful."

"Yea, I heard that before," John scoffed and took another drink from his glass.

Michael ventured another sip and again pulled his face grotesquely. "Aha! You

know, this is a funny old country, too, this is."

"Why is that?" asked his brother.

"Jesus how do I know that, sure I've only just come here."

"Now, you don't need tell us that," his brother sneered.

"Tis, though," continued Michael. "See, those men there. They're not talking to

one another. No one here talks to anyone, hah?"

John jerked his head first one way and then the other. "Will you for Christ's

sake watch what you're saying here, will you?"

"Why, what's wrong?"

"What's wrong!" Again John jerked his head sideways.

"Well, for one thing you're here now, and you don't talk here the way you did

when you were going down to the bog."

"Ara, Jesus, wasn't our bog on top of a big hill. Didn't we go up to the bog.

Jesus, you've an awful short memory."

"Right, up to the bog then," John snapped impatiently.

"Yes, that's it. Well, that's what everyone had to do round our place. Ah, God

surely you remember that?"

John sucked in his breath quickly and made a low whistle.

"Well, may bad luck to that bloody hen," he muttered.

Then he spoke calmly, emphatically, but in a low voice: "See, a lot of people

round here don't like the Irish. Shush, will you!" he warned hotly, just in time

to prevent Michael from saying something. "For Christ's sake, listen, and don't

make an ass of yourself all the time. Well, it all started with the 'economic

war' well, that made things worse."

"What war's that? Jesus I never heard of no war." "The tariffs, then, the

tariffs, but they call it here the 'economic war'. Now do you see?"

"Ha, Jesus, them tariffs are awful," remarked Michael.

"Sure they've robbed nearly everyone round our place. Sure you can't sell nothin'

now. That old De Valera wants shootin' 'cause he's made it awful bad over there

now."

"He's made it bad here as well," John added, stretching again for his glass."

But, then, our own don't help shouting and roaring, drinking and fighting all

over the place. They'd sicken you," and he drank deeply, then replaced his glass

on the floor." Then, be Christ, as soon as things get a little bad, they swarm

into London like a lot of bees. You can't stir for 'em, never mind get a job.

They're coming over now faster than ever. Every day Euston is flooded with

them."

"And sure what can they do? Sure, no one can make a living over there now."

"I wish half of them'd jump into a boghole and get drowneded," John sneered.

"Christ, it wouldn't be as bad if they spread themselves about a bit and some of

'em went somewhere else. But no, here, London all the lot. And all they're doing

is making it bad for everyone. Thousands of blokes who've been here years, and

thousands of people born here are out of work now because cf them. Still, over

they come, drove after drove. It's no wonder the people don't like 'em. They

can't," and his top lip curled up into a venomous grimace, proving the fact that

the smallest speck placed strategically before the eyeball obscures all the

imperfections of the world from the affected viewer.

"See, that man we live with?" he asked after having a nerve-relieving sup from

his glass.

"Jesus, didn't I think she was a woman," replied Michael.

"Tct, tct, tct! Her husband, I mean. No, you haven't seem him. Well, he worked

in a factory 'til lately. Now he can't get a job. So, what's he going to think

when he sees the rake of suitcases arrive every day at Euston? Trouble is the

ones that've been here years suffer as well as the latchikoos that've just come

over." He emptied his glass and held his hand out for Michael's. "Finishing

that?"

"Oh, Jesus, no. Sure, this'll do me now, right enough."

John rose, walked to the bar and ordered another pint for himself.

"And what can they do, they who've just come over?" Michael asked his brother as

soon as he returned to his seat. John didn't answer.

"What do you think?"

"I think same as nearly everyone else thinks there're about twice too many

Irish in London now for all the work there is. But if they'd go somewhere else

for a change, it wouldn't be as bad, but no, here, every bloody one. They'd

really bloody sicken you, they would."

During the course of the night, John drank three pints, but Michael contented

himself with just one, although he did empty his glass before closing time on

this occasion. Then he and his brother began the journey back to the digs.

It was obvious that Michael had listened and noted his brother's warnings, for

not on a single occasion did he raise his voice above normal during their

journey home.

John opened the door as noiselessly as he could and both groped their way to the

bedroom. Michael never mentioned the word 'supper'. Scarcely had either one's

head rested on his pillow when he

was asleep, and both remained in that helpless but blissful state until the

small alarm clock awoke them next morning.

Michael was so tired that he couldn't believe at first that he had been asleep

all night, but the thought of working, of earning money spurred him on, and he

soon forgot his tiredness and even urged his brother to hurry. He wanted to get

to that job, and as the minutes ticked by, a thousand disconcerting thoughts

flashed across his mind and unnerved him more than he already was.

But his brother was understanding, at least about that. He knew how the lad felt

and he knew how to assuage the lad's fears and anxieties.

Michael (Mick) Weaver

Thought for Today

The police may protect us

from the mob,

but who will protect us

from the police?

Bill Eburn

(London Voices)

In Ayrshire Now