|

ISSUE 24

cover size 210 x 148 mm (A5)

CONTENTS

EDITORIAL

By now an edition of Voices should need little introduction and in that way I

could be stuck for words. I've always been an admirer of Voices, its real down

to earth nitty gritty literature, not a bit high flown or pretentious. And in

this way it shows the great potentials of British working class literature.

The thing which gives Voices its personality and character is the fact that it

is written and put together by working folk. To say these people round Voices

and the Worker Writers are ordinary folk seems an underestimation of the amount

of time they put into their literature after they've not only come home from

work but tended to their families. It shows the power of the working people that

we are capable of this.

Voices and the Worker Writers movement have stood out as an alternative to the

career writer, the hobby writer, and consumerised and glamorised friction.

We've seen writing as an area of self help. And ourselves, our workmates and

neighbours are our market, if market is not too vulgar a word.

Our alternative is to see writing as integral to our everyday lives. We are not

divorced from what goes on around us, we do not isolate ourselves to write and

thus become hermits, neither do we write because we are hermits. We live and

experience our lives to the full and then in our spare moments we write it all

down whether as poetry or prose. In this way art belongs to the people and comes

from the people. Our art is not as divorced from real life as say the

all-American car chase. Through our work we can draw on much more real and

interesting aspects of our lives than the fictionalised cop and robber

shoot-outs which popular commercial fiction relies on. We do not try and

oversimplify life but find romance, humour, emotion and consolation in our

everyday lives.

If our writers are amateurs they are not amateurish, but are like amateur

sportsmen, musicians and entertainers. They (We) aim to win through. As an

alternative to the conventional media we are no soft option, the writers here-in

have worked very hard to make sure they communicate, no matter how many

preconceptions of what previously constituted literature they've had to push

aside. They've edited their work, they've rewritten, they're grouped their ideas

into paragraphs; and discussed their work in workshops up and down the country.

They've struggled to recapture moods and by-gone eras. Their work has been the

reason behind domestic arguments and giggles at work; and most importantly their

work is the product of much encouragement from their families, friends and

fellow writers. These writers are as everyway fanatical about their work and

probably a darn sight more enthusiastic about it than those who are lucky enough

to make a career out of writing.

Inside and outside of Voices we have been saying for years that in Voices' pages

we want to see more writing on the Nuclear Threat and more writing by black and

women writers. We can only express and reflect the entire spectrum of our lives

if black conscious and feminist writing appears in our pages; and to this aim

Voices does discriminate in favour of black and feminist writing. We want no-one

to be looking at the mainstream of working class writing through rainy windows.

So Voices belongs to all of us.

The first and foremost story in this edition is the first instalment of a four

part serial by the late Michael (Mick) Weaver. He is well known for his

political and trade union contributions to the life of the South Lancashire

mines and community. May we thank his widow Molly for enabling us to enjoy what

must be one of the best stories Voices has ever had the joy to publish. The best

way to ensure you get to read all four parts of this serial is to take out a

subscription!

We also carry tributes and poems in this edition, on the deaths of worker

writers Mary Casey and Vivian Usherwood. Also it is with much sadness that we

must report the recent death of Ray Mort, a Commonword Writers' Workshop full

timer. He wrote plays, had been a teacher and was a plumber by trade. He will be

remembered for the great encouragement he gave to a great many writers in

Manchester and surrounding country.

In closing my editorial may I thank all of the people who make Voices possible,

especially the readers; and particularly Rick Gwilt the editor who keeps Voices

together so admirably, and has shown sufficient confidence in myself to push me

to edit this edition.

John Gowling

(Manchester)

May 1981

Breaking the Silence

I'm writing this as a result of attending my first ever Voices editorial

meeting. At the end of the evening we had chosen 14 pieces for Voices 24 2 by

women. When we looked back to material submitted there was the same pattern.

Why? Well, I think Wendy's editorial in the last issue of Voices spells that out

very clearly. I, too, feel that the editorial page of Voices should be used to

examine the debate on women's writing within the worker-writer movement but,

equally important, that women's writing appear in Voices to be read.

A recent study of the history of women in literature in this century came up

with the figure of "one-out-of-twelve" writers of achievement being a woman. A

similar ratio in Voices was quoted by Wendy.

In past issues the editorial group has shown its awareness of the need to

change, and the worker-writer movement must be seen as playing a large part in

that "moving away from propagandist writing (Editorial Voices 22) and towards

writing in which people draw more directly on their own experience." It's now up

to women writers to put Voices to the test.

The American writer, Tillie Olsen, speaks of how "we who write are survivors"

and goes on to spell this out as bearing witness for those who founder; trying

to tell how and why they, also worthy of life, did not survive; and passing on

ways of surviving.

Voices is offering women writers the chance to break that silence.

Patricia Duffin

(Gatehouse Project, Manchester)

MICHAEL'S STORY

Introduction by Molly Weaver

In 1917 on December 23rd in the home, Michael Weaver was born in the Republic of

Ireland, in County Roscommon, in a small village at Calvagh, at the home of his

grandmother, Margaret Sherlock, with whom he lived until the age of fifteen,

attending school, and helping to farm the land for the livelihood of himself,

his grandma, and his dog.

At this age he was compelled to come to England, as work in Ireland was

non-existent. He did this rather than stay behind for a college education since

that was only designed in a way which he would have had to become a priest. This

was not his ambition, having seen quite a great deal of struggle in the country,

resulting from the terrorist regime of the Black and Tans. Having landed in

England he joined the growing masses of the unemployed. He searched the country

far and wide for work on the farms, roads or land, until he obtained something

steady on the London underground. From there he moved onto quarrying, then to

road work.

In 1941 I met Michael for the first time at Chequerbent, between Bolton and

Westhoughton. His work at that time was heading a gang of men on a construction

in Leyland.

Later that year Michael went mining at Mosley Common in South Lancashire. He had

applied for the Royal Navy but they had not even acknowledged this. From going

in the mine he was in a tied job for the duration of the war. He made up his

mind right from then that he would be settled for the rest of his life. He was

already a member of the Communist Party and a close friend of Jim Hammond,

miner's agent of the day.

Michael was on the branch committee of the NUM and in a few months of joining in

meetings he was voted delegate to represent his colliery at area level, then

voted to executive committee level delegate. Soon after the committee had him

voted part-time union secretary.

In 1956 he opposed the then union secretary William Birmingham for full time

union work and swept the board clean. He took to his new job like a fish takes

to water, with a determination that miners must be respected for the loyal

service they give to his country.

He forwent much free-time to ensure they got their rights, he battled for

concessionary coal, visited homes taking statements from sick people at

weekends. In order that I myself might have the pleasure of his very magnetic

companionship, and the need I had to be with him, I would go to these sick and

sadly injured people, seeing and sharing their suffering.

I think in some way I helped, at least I hope, to keep him together. Michael

will be remembered for a great personality as well as the work he put in. In the

late years, I cannot give a date, but Michael was invited to visit China,

looking for knowledge and their mining methods. But the Republic of Ireland

would neither give him a passport nor a reason for this. In 1961 he went through

the same channel with the same negative result. This time he wanted to go to

Russia. He thus had to choose, his application was made and granted through the

British Embassy. So he went to Russia for almost a month.

Michael travelled the mining villages of this country as mine after mine was

closed following this up with TV confrontations with our so-called experts on

how oil would replace coal.

He saw into the future, the disasters these closures would make, and all honesty

his predictions have come true. Then in 1968 they sank Mosley Common I think it

was then that Mick Weaver Union Official Unique began to die.

He had stood for parliament and only failed to get there because of his

communist beliefs. He was no short cut man and he never went back on his

principals.

He took up writing when he could no longer work, as he became really bad with

arthritis, he wrote for five years. His life ended very suddenly on Thursday

29th January 1976 at 1.50 p.m.

He left a legacy of love ... his wife, his son Michael; two daughters Eileen and

Joanne; and our daughter-in-law Penny.

Molly Weaver With love to Michael

Michael's Story

EPISODE ONE

John McWanted was a small farmer in County Mayo, Ireland. He was a hard,

uncouth, stern man, merciless in anger, but not unreasonable when in a good

humour, which didn't amount to much, anyway, because it was very seldom he was

in a good humour. He had never been to school a day in his life, for when he was

a boy, authority did not provide schools for peasants' children.

He had four sons, the youngest of which was Michael, and long before any of them

had reached manhood he had all their careers and obligations mapped out for

them. The eldest, called John, would go to England as soon as he turned sixteen

years, earn money there any way he could, and send most of it home to help bring

up the rest of the family. The next two would also go on reaching sixteen years

of age and the youngest, Michael, would stay behind and inherit the place, just

as he, John McWanted, had inherited the place from his father, being the

youngest son of his father's family.

In the west of Ireland this was a tradition that had become so ingrained in the

pattern of peoples' behaviour that each member of a family accepted without

question or fuss the tasks and obligations that fell to him or her by the

accident of birth and tried to perform those tasks and discharge those

obligations dutifully and honourably. John McWanted had no reason to assume that

his sons would behave any better or worse than his own brothers had done, or

that the sons of thousands of small farmers had done, so he actually looked

forward eagerly to the day the eldest of his sons could emigrate, which would

ease the burden of poverty he carried, and to later days when his other two sons

would join his eldest in England and make things easy for himself and his wife

in their old age.

His eldest son's birthday fell on the twentieth of June, nineteen-twenty-nine,

and first thing in the morning, with a song in his heart as tuneful and

exhilarating as a yellowhammer, John McWanted set off walking to the local shop

to buy a suitcase. That night, he packed all his son's belongings in the case

and made all preparations for the big event the following day.

"Sure, we'll soon be on a pig's back," he said to his wrinkled, headscarved wife

as they sat by the fireside that night. "Sure, in another couple of years,

there'll be another one ready, and two years after that another. Ara, devil a

one of usll feel a thing now 'till they're all away, and then all we'll have to

do every week is change the cheques." He laughed closely to himself while his

wife contended herself with nodding agreement, and fixing more peat-sods on the

fire. "Ara, they'll sink the old boat with all the money they'll shove over when

they all get going," he continued. "Jesus, you know they're great lads. Sure

that John can do more work than any man now, and he'll get better all the time.

He will." He eased out his legs, drew heavily on his pipe and looked at the few

ornaments that adorned the wooden mantelpiece over the fireplace. "Wasn't it him

made that?" and he pointed up to the mantelpiece with the stem of his pipe. "Twas,"

his wife replied, then sniffled and sighed. "Sure that's a fine piece of work

altogether. Sure a man that can do work like that'll get on anywhere. Ah, we've

nothin' to worry about now, nothin' at all. The money'll start coming soon,

you'll see."

The following morning, John McWanted walked proudly to the nearby town and

carried his son's case. At the railway station, he paid the lad's fare, gave him

an extra pound just in case something unforeseen happened, and with a broad

smile, a warm handshake, and a final goodbye wave, he launched his son on the

journey to England, another 'Spolpeen' to swell the ranks of Irish immigrants

there. He walked home more slowly, still with joy in his heart and a sense of

great expectation pervading his mind, for he felt that all he had to do was wait

a little longer and then the money would start rolling across the waves.

But the money did not come rolling across the waves, for in nineteen-twenty-nine

England was experiencing a serious economic slump and work was very hard to come

by.

Of course, John McWanted made no allowances for that, for he never would accept

excuses for anyone else's misdeeds, that is. So he heaped all the blame on his

son, and every morning when he asked his wife:

"Any letter from the quare fellow today?" and she told him:

"No," he became ever more sullen and bad tempered.

"Ara, sure I knew well that fella'd never come to nothin'," he told his wife.

"Sure, he never thought of nothin' but himself. Nothin' in the world. He's there

now beyond in England, drinkin' himself stupid every night and not a thought in

his head for us here at home. Ara, may the devil whip him, sure he's no good for

nothin'. Now we'll have to wait 'til the next one's ready. See what sort of job

he makes of it."

His wife didn't speak, just nodded dutifully and got on with her housework.

"You know, I think meself the next one'll be better. Ara sure he has a great old

head on him, a great head altogether. Sure he's twice the man the other fellow

was." Again Mrs. McWanted merely nodded, for she knew she daren't cross her

husband when he was in an angry mood, and he was in an angry and recriminating

mood then.

John McWanted's second son was ready for dispatch in nineteen-thirty-one. The

same ritual was observed, the same expectations cherished and the same result

ensued no money, for unemployment still raged in England and wages were so

savagely depressed that single men could just pay their way when in work, while

men with families merely lived.

Once more John McWanted's disappointment was enormous and his anger fearsome. "Ara,

wasn't that the bad arab all his life," he snarled to his wife. "All his life,

he was." Uneasily she tried to get out of his way and out of reach of his

penetrating stare, for although she did not agree with him, she dare not appear

to disagree with him.

He continued cynically between puffs on his pipe.

"An' the, the old gleck of

him, like a right man. Haa! two nice yokes, the pair of 'em. We have only one

left now, and if he doesn't do something, we're buggered. We are, buggered. But,

what am I sayin', won't it be two years yet before he can go. That the devil

whip the pair of them beyond there in England! Weren't they the bad rearing!"

The third son left Ireland in nineteen-thirty-three and John McWanted's wrath

became pathological. "I've a good mind to kill myself," he often murmured.

"Sure, I'm 'shamed to show me face at the chapel gate a Sunday morning, with me

having three sons beyond in England, and me still wearing the same old suit I

wore ... Jesus I don't know when. I don't know where they took this drinkin'

from," he remarked angrily to his wife. "It must be from your side, 'cause it

wasn't from mine. Jesus, my side were great people altogether. Sure, they'd kill

their own ... well I won't say it, but they'd commit murder for a penny, they

would. Sure them old dowderies on your side were no good for nothin'. No good

for nothing!" and as he whipped himself into a frenzy, his wife quietly slid

away, lamenting the fact that she didn't know where her three sons were, how

they were faring, or anything at all about them. And she was often heart-sick at

her husband's rantings, but she had to hide her feelings. That was the hardest

part. She begged God in her prayers to urge them to write to her, even if they

had no money to send, but she feared they wouldn't do that, for she had no idea

that all three thought that an empty letter would not be welcomed in County

Mayo. And, indeed, it would not be welcomed by John McWanted.

Things became worse for the Irish small farmers. The 'Economic War' hit them

savage blows. The price of everything they had to sell hit rock bottom, while

the price of everything they needed to buy remained stable or increased. So

finally, the last of John McWanted's family, Michael, decided to emigrate to

England. This time there was no fuss over the leaving, no proud walk into town

and no sitting back with mounting expectations.

The morning Michael left home his father acted normally. His mother cried

silently, inwardly, but Mr. McWanted sat coldly smoking his pipe as his youngest

son, carrying a small suitcase, left the house. The year was nineteen-hundred

and thirty-five and Michael, still little more than a boy, considered himself a

man and was determined to behave like a man, work as hard as he could in

England, save up like hell and send as much money as he could home to his

stricken father and mother. He had been listening so long to his father's

rantings about the awful drinking habits of his elder brothers that he had begun

to believe them, and vowed that he would not be like that. He vowed that he

would avoid drink at all costs, and he renewed that vow before he left the small

railway station at the nearby town and several more times on the journey to

Dublin.

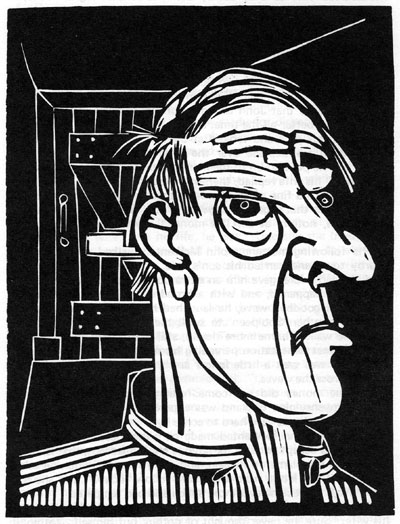

Michael McWanted arrived at Euston Station on a chill, wet, October day. He had

nothing to eat since he left home, so he was tired and hungry, but the only

money he had was a pound note his mother had cabbaged from her housekeeping

pittance and had slipped into his pocket unknownst to his father.

When Michael got off the train, his eyes fairly bulged with surprise at the size

of everything. "Jesus, it's bigger than Dublin," he muttered to himself. "Jesus,

it's enormous!" and he looked all round, his eyesight diffused with wonder.

"God, I bet a man'd soon get lost here, if he didn't know where he was going.

And sure I don't know where I'm going, so I must be lost, then, so I must." and

he walked out through the huge columned archway.

Outside on the street, he stood for several minutes undecided which way to turn.

Then he remembered the tales he had heard about the wonderfully helpful English

bobby, and he decided to ask the first one he met. He didn't rightly know what

to ask, but he thought that the bobby, being wonderful and helpful, would know

how to help him. With his suitcase held limply in his hand he approached a bobby

who happened to be a man who was on his way to take up his position on point

duty - and he stammered out disjointly and hoarsely: "P.p.please sir....

p.p.please ... ?

"You what, mite?" the bobby barked angrily, and scornfully eyed Michael all

over.

"P.p.please sir, could, could you tell m.m.me where I might meet some Irish?"

"Yes, mite. Get back to fucking Ireland where you fucking well came from." He

brushed past the bewildered Michael and shouted over his shoulder as he went by:

"And take a half a million of those fuckers here with you, too. You can drop the

bastards off half way there if you like."

"Oh, God save us all!" moaned an astounded Michael. "Sure, he wasn't friendly at

all. Not a bit friendly, he wasn't. Aha, but maybe that's the way they have here

of telling a man they don't know ... or something. I bet it is." He turned to

his left and began walking casually along the street.

Coming towards him was a man wearing a moleskin trousers, a heavy pair of boots,

a long, thick, black jacket, a khaki shirt, a black scarf wound carelessly

around his neck with both ends flapping over one shoulder, and a cap set at a

rakish angle on the side of his head. He rolled from side to side as he walked

and Michael immediately concluded that he was Irish, for he had heard that

Irishmen who had lived in England a long time and had worked on very big jobs

dressed that way and walked in that manner.

"Jesus, this fella must've been here a shocking long time," he told himself as

he looked at other passers by. "Jesus, he's been here longer than anyone else,

and he must'ave worked on some quare, big jobs, too, to wear that lot. So, he's

sure to know."

As the weird-geared one rolled closer, Michael hung out his most pleasant smile

and began hesitantly, but not nearly as hesitantly as when he had addressed the

bobby: "Please, mister, could you tell me where I could meet some Irish blokes?

Ara of course, you can. Sure why wouldn't you!"

The weirdly-dressed never stopped but snarled out of the side of his mouth: "Get

fucked, you stupid greesheen, you. Get back to the bog where you came from!"

Michael's mouth dropped open with astonishment and his eyes followed the

mole-skin clad legs along the street until they were out of sight. "God bless us

all!" he expostulated, still looking after the weird one. Then he dropped his

head to one side and murmured to himself: "Sure, Jesus, I bet everyone here

talks like that now, the Irish and all, well, them that's been here a long time,

anyway. God, your man there must've been here a shocking long time all right.

But, be Jesus, it's a quare way of talking, just the same. Ah, but... what harm.

Sure it must be the right way or they wouldn't all have it. Be Jesus, I better

start talking like that, too. Ara, why wouldn't I. Jesus, sure I know all them

words right well. 'Course I do. I will."

So resolved, he turned to continue his journey, and as he did so, he swung his

suitcase out and accidentally struck a passing woman a painful blow on the knee.

She sucked in her breath quickly, scowled fiercely at Michael and released a

shoal of words which he didn't understand, but which he thought had a ring

similar to the words used by the other people he had encountered.

"Ah, now," he reflected, "by Jesus, the women talk that way, too, here now. Ah,

now, I'll have to talk the same way, too. Sure, a man'd look a proper gobshite

if he didn't talk like everyone else, sure he would. Oh, now, indeed, I will. Be

Jesus, though, I bet they're grand people if a man knew them properly, so they

are. Hah? Ah, but damn me if it isn't a quare way of talking, just the same. Ah

... well ... what harm. I'll do it, too sure."

A little further along the street he saw a man who appeared middle-aged coming

towards him. The man wore heavy boots which were bleached white-brown with clay,

but he didn't roll when he walked and he didn't wear moleskins or a scarf and

his cap was straight on the top of his head.

"Ah, he won't be long here," Michael told himself," and he won't have worked on

any big jobs either. But, be Jesus, he might be able to help me just the same.

Jesus, I'll chance him anyhow, but this time I'm going to talk right to him.

When the older man was within a couple of yards of him, Michael stood still, put

both heels together and shouted at the top of his voice: "Scan, could you

fucking well tell me where I could meet a few fucking Irishmen in this man's

town, hah?"

"Bow-wow!" barked the older man and staggered back as if he had been hit in the

face with a brick. He eyed the young stranger carefully, paying particular

attention to the lad's clothes, his demeanour

and the suitcase which dangled loosely from his hand and caused passers by to

veer one way or the other in order to avoid being hit by it.

"Just come over?" he asked cautiously.

"Oh, now, just, just pulled into the fucking old station there."

"Shush!" screamed the older man, grabbing Michael's arm and snatching him

quickly to one side. He glanced quickly over each shoulder before he spoke

earnestly to the young lad.

"See, you mustn't talk like that here in the main street or they'll have the

bobbies on you."

"Bobbies?" enquires the confused Michael. "Is it the police you mean? Sure, damn

me wasn't it a f...."

"Such will you!" roared the older man, fretfully glancing once more over each

shoulder. "Now listen, you must not talk like that here in the public street, or

anywhere else in public, for that matter. Now, at work everything goes, but on

the street ... no. Someone'll set the bobbies on you, you know."

"Geraway!"

"They bloody well will."

"Sure damn me wasn't it a policeman I first heard talking like that, and wasn't

the next one an Irishman, and one that'd been here a long time at that."

"Now, now, listen," warned the older man, "you must not use that sort of

language here in the streets. Only old tramps use that sort of language here."

"Be Jesus is that true? Well damn me isn't this a marvellous country. They have

tramp bobbies here. Hee, hee"

"No . . . Hah? Ah ... now . . . well," continued the older man, unsure what to

say, "never mind that, now, where are you headin' for?"

"Damn me if I know properly," replied Michael. "I have three brothers here, but

I don't know where they are, and, Jesus, I bet it'd be awful easy for a man to

get lost in this f........"

"Haaaaaa!" coughed the older man as loudly as he could hoping to drown out the

young lad's swear words.

"Christ, have you a bad throat, or something?" asked Michael.

"No, but you have an awful tongue. Now, unless you stop that, I'm telling you,

the bobbies'll have you. Now, I'm telling you."

"Jesus, do you mean it?"

"Do I mean it 'Course I mean it. Now, where did you say you're

headin' for?"

"Sure I don't know. Sure, I have three brothers here and I don't know where one

of 'em is. Do you know?"

"Ara, how the hell would I know where your brothers are? Sure you haven't told

me who you are yet."

"Oh, be God, no, I haven't. Michael McWanted, that's me. Well, that's me name

anyhow."

"McWanted," browsed the older man, rubbing a grimy, stubbly chin with a dirty

hand. "Did you say you have brothers here?"

"I have, indeed, three, but....."

"Jesus, I work with a McWanted. You're not from Killoween by any chance?"

"Oh, now, the very place, the very place."

"Jesus, the bloke I'm working with might be your brother, but he's a lot older

than you."

"It'll be me oldest brother, that's who it'll be. A big bloke with fair hair and

a grey, striped suit. Ah, but sure he might have bought another one since then.

His name's John."

'The name's John all right," the older man said, "but he's not all that big,

though. Oh, but, a handy bloke, a nice handy-sized bloke. Jesus, he could be

your brother all right, 'cause his name's McWanted and he comes from Killoween."

"Oh, he is, he is, he is, no doubt about it at all," enthused Michael. "Jesus,

where can I find him, tonight? Now? Hah? Jesus I hear he's a bugger for the

beer, hah?"

The older man shook his head, for Michael's artlessness was becoming perplexing,

and he kept swinging the suitcase about as he spoke. "Hi! keep that old bag

steady, will you?" warned the older man. "You'll knock some one's chips out..."

"Yes, sure, sure, sound" Michael assured him, and he managed to hold the bag

steady for a while, at least.

The older man spoke again: "Now, well, if that's your brother .. "

"Oh, it is, it is, no doubt about it," Michael interrupted.

"Can you tell me where I can see him?"

"Wasn't that what I was trying to tell you, but you wouldn't listen."

"Oh, I will, I will, definitely. Scan, sound!"

"Right then. Well, now, if that's your brother, you'll find him within in

Hammersmith 'cause that's where he lives."

"Hammer who?" Michael enquired earnestly.

"Smith. Hammersmith."

"Jesus! who in the world's that?"

"Who! it's a place, not far from here. You can take a bus there. I mean, you can

catch a bus here that'll take you there," he added just in time to prevent

Michael's intervention.

"Phew!" he exhaled loudly. "You catch a number .... but what in the hell's the

use telling you that. Sure, you'll end up in Smithfield if you're left on your

own." He pondered everything lengthily and then said, as though inspired:

"Tell you what . . . but first let's get rid of that bloody case, for Christ's

sake!"

"Get rid of it," exclaimed Michael. "Sure, this is all I have in the world."

"NO, I don't mean that. I mean, put it somewhere."

"Sure, if I put it down, won't someone pick it up and walk away with it? And

won't I be buggered then altogether?"

The older man sighed deeply, for the situation was becoming impossible and

Michael's gullibility unbelievable. But, the nobler nature within him stirred',

and he decided not to leave such an ingenuous, unsuspecting, young lad to wander

the streets of London alone, a prey to all the guiles of the very dangerous

people who abounded in every side street at that time. Yet, what to do was the

problem. "I think ..." he began but broke off without saying much. "What time is

it?" he looked up at the station clock and saw that it was half-past six.

"Christ, two hours yet. See, he won't be out for another hour and a half, maybe

two. But let's get rid of that bloody bag..."

"Get rid...."

"Now, now. Say nothing, just come on," and they began walking towards the

station. "See, there's a place here where you can leave it. It'll cost you

twopence or maybe threepence, but it'll be safe, and it'll be there where you

want it. See? Oh, give's the bloody thing here, for Jesus' sake!"

The older man snatched the case from Michael, walked straight to the left

luggage department, put the case on the counter and asked the attendant: "Twopence

or threepence?"

"Two, mite?," replied the attendant, picking the case off the counter, stacking

it with many more on one side of the compartment, and writing out a receipt.

The older man paid the twopence, took the receipt, then handed it to Michael.

"Now, isn't that better?"

"Oh, great, great, sound!"

"Well, you won't hit anyone in the cod fillets anyway."

"Jesus

"Now, now. It'll be there when you want it. All you have to do is hand that

receipt to the bloke there and he'll give it to you."

"Oh, great, great, sound. Jese, thanks a lot. Be God, I never asked you your

name, have I?"

"No, well, don't. Just keep it that way. Come on," and as they walked away from

the left luggage department, the older man talked confidentially with his

younger colleague. "Now, let me give you a bit of a tip here."

"Yes."

"Yes. Well, it's not a wise thing to start bandying names about all over the

place around here just now."

"No?"

"No. See, the bobbies are awfully keen around here just now. What, with this

'Economic War' and that, a man's a lot better to keep quiet. Know what I mean?"

Although Michael had listened very carefully, he didn't really understand what

his older colleague had been trying to tell him, but he replied as if he had.

"Oh, yes, 'course, sound!"

"Tell you what," continued the older man, "call me Jack. How's that?"

"Oh, fair enough, fair enough."

"That'll do for now, won't it? Well, I'll come for it anyhow, so what more does

a man want?"

"Oh, no, nothing, fair enough, sound .... Jack."

Then they both laughed and that was the first time Michael had heard anything he

thought worth laughing at since he had left home.

"Right, now I'll tell you what," suggested the older man as they left the

station. "I have a bit of an old room up the road here a bit. Now, we can go

there now, have a drink of tea and a bit of grub, if there is any, then after

I've had a shave and a change out of this lot. I'll have a run into Hammersmith

with you."

"Run!" Michael expostulated. "Jesus, sure I don't want to start running..."

"Now, now, will you! I mean, we'll catch a bus to Hammersmith, how's that?"

"Oh, powerful, powerful, great, sound."

"Phew!"

They didn't speak again until they arrived at Jack's lodgings. It was a small

room which Jack rented. There was a single bed under the window and a small

table in the middle of the floor with two cane chairs tucked underneath it. The

table was covered with newspaper and on it stood a motley of knives, forks,

spoons, greasy plates, a teapot and a tea-stained mug.

"Sit there 'till I get something ready," Jack instructed, setting one of the

chairs near the empty fireplace. Michael sat timidly on the chair, but kept

looking round the room, for it was not the kind he had expected to find in

London, and certainly did not accord with the splendour of Euston.

Jack put everything on the table into a tin basin and carried them into a

kitchen which he shared with other boarders. Then he brought back some clean

newspaper and covered the table with it. Next he brought two mugs, two pairs of

knives and forks, two plates and a loaf of bread. "Hah! well, we'll have a bit

of grub whatever happens, even if the sky falls," he joked and skipped nimbly

into the kitchen once more.

Michael rubbed his palms together vigorously in anticipation, for he felt like a

spent salmon, and the gastric juices were gnawing at the linings of his empty

stomach.

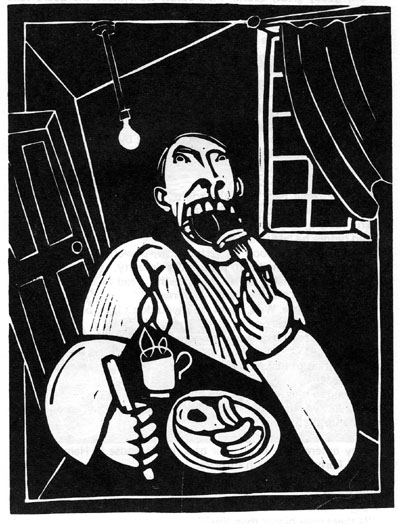

Not long after that Jack was back with a huge frying pan in which he had cooked

bacon and eggs. "Hah! a bit nearer," he said as he left the pan on the table and

hurried into the kitchen once more.

The smell of the cooked bacon nearly drove Michael to distraction and he had to

struggle with himself for all he was worth to stop himself from attacking the

food. The battle for self control was at a critical stage when Jack returned

from the kitchen carrying a teapot. He divided out the bacon and eggs, cut

several slices off the load and dropped them on the table centre and poured out

the tea.

"Right me son!" he shouted "up to the manger."

The words had hardly fallen from his lips when Michael was at the table, having

dragged his chair behind him. They never spoke during the meal, but once or

twice Jack looked across at his colleague who was eating like a semi-starved

animal.

"A bit better?" Jack asked, when they had finished eating and were languidly

sipping tea.

"Better, oh, what!" Michael replied.

"Well, a bit tighter, anyhow. Well, now, I'll tell you what we'll do well, in

a few minutes, I mean, when we've finished this drop of tea. I'll have a shave,

change out of this habit and I'll run into Hammersmith with you, and we'll see

the quare fella. Hah?"

"Run!" Michael exclaimed, then remembered and a vapid look spread across his

face. "Oh, you mean .... bus."

"Yes. That's what I mean. Yes .... Oooh!"

"Oh, good, great, sound that. Jesus, we'll meet the quare fella tonight. Think

we'll find him?" and for the first time while referring to his brother a hint of

doubt dimmed Michael's exuberance.

"Find Him? 'Course we'll find him. I know right well where he'll be, no fear of

that."

"You do? Oh, Jesus that's great, great altogether."

"I won't be long," Jack explained as he left the room.

"There's an old evening paper there you can have a look at while I'm getting

ready. Right?"

"Right, right, oh great. Jesus, you're a sound man."

Jack hurried up the stairs, and Michael sat by the table stock still, while in

his head fear and intrepidity, disappointment and exultation regularly changed

places.

When Jack came back into the room, he was clean shaven, wore a fairly well

preserved blue serge suit, a white shirt with a collar, a blue tie and looked,

in Michael's eyes, several years younger than he had looked before he left to

change his clothes.

"Jesus, man, you look powerful, now, powerful altogether, you do," Michael

exclaimed with the utmost sincerity.

Jack smiled amiably as he fixed on his head at a jaunty angle a dark, pork-pie

hat. "Right, now, scan, ready?"

"Ready? 'Course. Well, damn me if you don't look powerful.

"Right then, come on, we'll go."

As they were going out. Jack squinted at a clock in the kitchen and announced:

"Just eight now. Nice time. We'll be there for half-past, with a bit of luck.

That's when the quare fella comes out."

"Well is it?"

"Yes, not a minute before, any night."

Jack locked the door and they walked steadily, shoulder to shoulder up the

street.

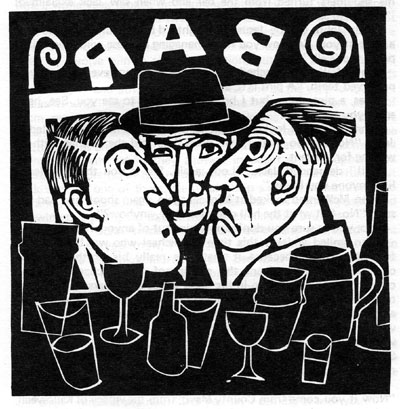

As they entered the public bar of a public house in Hammersmith, Michael fairly

oogled with surprise.

"Jesus, this is an awful big place," he said, scanning every corner of the room.

"Big?" remarked his colleague. "Not it."

"Is there ones bigger than this?"

"Bigger than this? Ger away! Why, they drink out of glasses bigger than this in

some places."

"Jesus, they must be fantastic glasses. Can you see the quare fella at all?"

"See him? Isn't he there fornint you."

"Hah? Where?"

Just then a slightly built man in a grey suit that hung loosely from his

shoulders turned from the bar and when saw Jack exclaimed: "Why, hello Jack.

What's brought you to these parts?"

"Hello John. Oh, be Jesus, I thought I'd have a run in here to have a look at

you. See how you're all managing in these wild, uncivilized parts, that's all."

John McWanted laughed and showed a clean, even set of well-preserved teeth. "A

pint is it. Jack?"

"Yes, a pint, John, but I brought someone to see you. See, here, see if you know

him."

John McWanted looked at Michael, shook his head and smiled at Jack. "No, but no

matter, two pints," he told the barman without waiting for consent.

"Hi!" demanded Jack. "Look again. See if you think he looks like anyone you

know."

John McWanted looked at Michael again, again shook his head and said: "No. But

what the hell does it matter, anyhow?"

"So, you're sure you don't know him out of anyone?" John smiled amiably this

time at Michael who was beginning to feel despondent, because if that was really

his brother, he had changed completely from the picture of him Michael had been

carrying around with him in his mind for several years. Michael was only ten

years old when his oldest brother left home, and Michael always pictured that

brother as being a very powerful young man and very stylish. But the man in

front of him wasn't like that at all. He was slim with a wrinkled neck and wore

a suit much too big for him. Still, he was friendly, laughed continually and

that sat Michael's mind at ease.

"Well, this is great," remarked Jack as John paid for the beer. "Now if you come

from County Mayo, from the village of Killoween, and your mother never took in

lodgers, this is your full brother, Michael."

"Hah!" shouted John. "Me brother?" and as he turned excitedly from the bar, he

spilled some of the beer.

"Oh, for God's sake," admonished Jack, "don't spill the holy water whatever you

do. Lord save us," and he took a pint glass from John and quickly sipped out of

it.

"Jesus Christ, it's not our Mickeen," John exclaimed and thrust out a washed,

but gnarled hand.

"That's me," Michael said exultantly and eagerly grabbed his brother's

outstretched hand.

Within the next few minutes, they shook hands more than a dozen times, while

Jack looked on from the outside, yet not feeling an outsider. For a long time

the two brothers talked about Ireland, about their father and their mother and

how difficult it was to make a living there then. Occasionally John deliberately

turned to Jack and tried to involve him in the conversation, but Jack understood

and was content to drink and listen to the two brothers exchange words and

thoughts and attribute, for Jack was one of the very few mature Irishmen who

liked young Irish lads who came to London. Most of them regarded the new

arrivals as unwelcome competitors for the little work that was available. In

fact, they often looked on those young lads as undesirable intruders, and

scoffed at them and mocked them, especially when they showed innocent and

unsophisticated attitudes to the harsh reality of living in economic-torn

Britain. But Jack was not one of those. He would help a young lad anytime, and

he knew he was doing exactly that when he was standing aside and allowing this

young lad to talk freely with his older brother.

Eventually John turned from his brother and addressed Jack: "Damn me, do you

know, I've a good mind to bring him out on the job with me tomorrow morning,

hah? See what the 'screech' has to say about him, hah? What do you think? Hah?"

" 'Course, 'course, do, why wouldn't you."-

"By Jesus, I will."

"Aha, but what about digs for the lad first," Jack reminded the older brother.

"He'll want digs you know."

Ah, Jesus, he'll be all right that way. Sure he can delve in with me for the

time being anyway. I was just saying to Jack here; you'll be all right for digs,

for a bit anyhow. You can stay with me for the time being."

"Digs!" Michael shouted. "Did you say I can dig in with you?"

"You can for what it is, like. The devil kill me if that isn't a good way to

describe them, too diggin in."

"Oh, well, be Jesus, if I can dig in with you, sure I'm made altogether. Sure

that's powerful altogether. Jesus, amn't I a lucky joker to meet two sound men

like you two, hah?"

Michael's enthusiasm was becoming so riotous that his brother was about to

intervene to calm the lad down, but Jack advised against that.

"Ara, leave the lad alone," he counselled, "Sure, what harm's he doing? Ara,

isn't it soon enough he'll know the other side. Sure, let him have his way now

while he has the chance. You know yourself, he'll meet the other side before

very long. Let the lad have his fling," and he drank deeply from his glass.

John nodded agreement. "I will, I'll do that. But damn me if I amn't thinking

about bringing him out there with me in the morning, what do you think?" Let's

see what the 'mouth' has to say, eh?"

"Course, why wouldn't you. Sure, he can only say no. But I won't be there

myself. I jacked this afternoon."

"You didn't?"

"Ara, I did. Ara, sure no one could stick that animal out there."

"Jesus, what was he on about today?"

"Well, be Jese, he never spoke to me today, but I was going to jack anyway.

Sure, animals like the 'shout' out there sack so many men every week, or make

them jack. That's how they keep their jobs. And everyone knows it's going to

come his turn one day. So, I didn't give him the chance to get round to me, I

jacked. Mind you, I had seen this bloke last week-end, and he's working in the

tunnels, widening that one that's going out to Morden. Ah, it's near enough sort

of work. So that encouraged me to jack, anyway." "And are you starting in the

tunnels, then?" "Oh, aye. Oh, Be Jese, the job's near enough." "Oh, sure, that's

great work altogether. Sure, a man's made when he gets in work like that."

"Aye. Well, there's one thing about it; a man won't have to put up with animals

like the 'shout'."

"Are, I don't suppose his type'd be any good at all in that sort of work."

"No, an' I'll tell you something else them blokes wouldn't stand him five

minutes. They would not, indeed."

"They wouldn't, I suppose."

"They would not. Ara, they're nearly all cockneys, regimental sort of men. Now

they wouldn't stand the likes of the 'shout' very long. I'm telling you. Another

thing; a man won't be bothered too much about the weather. He won't, as the man

says, he won't be listening out for a bray from that ass, anyway, raining men

off. He won't. But, you were saying, you're taking the young fellow out there in

the morning?"

'Yes, I was. Think it'd be wise?"

"Well, what can you lose? Nothing. And damn me I've heard that that animal isn't

bad with young lads."

"You've heard that?"

"I have, on my oath."

"Well, by Christ I'll test him in the morning, I will that."

"Do, of course, why wouldn't you?"

"I will. I was just telling Jack here that I'm taking you out on the job with me

tomorrow, hah?"

"Jesus, out on a job tomorrow!"

"Yes, think you'll be all right?"

"All right? Jesus that's powerful, powerful. Jesus amn't I the lucky man. Jesus,

sure I never thought England's be as easy as this."

Jack and John smiled slowly and prudently, for they suspected Michael's optimism

would not be long lasting. They nodded meaningfully to each other indicating

that they were anxious to let the lad have a good fling, because they suspected

that the harsh reality of life in a country torn asunder by an economic slump

which deepened and widened class divisions, sharpened class antagonisms and

extended class hatred to its extreme racism would soon shatter his first

impressions and premature illusions.

Despite all Jack's coaxings, Michael steadfastly refused to have more than one

glass of beer, so Jack eventually ordered just two pints and during the

remainder of the night, he and John drank steadily. Even when the barman shouted

'time', Michael had a half pint that he couldn't drink. He placed this on the

bar and the barman instantly whipped it off, together with other glasses. The

three men then walked leisurely into the street and stood on the pavement

outside the pub talking earnestly but quietly.

John thanked his colleague. Jack, over and over again for all he had done that

evening and night and vowed that he would return the compliment in full one day.

Then, after exchanging no end of 'so longs' and 'goodbyes', they went their

separate ways home John and Michael on foot to John's digs, which weren't far

away, and Jack by bus to the area in which he lived.

Michael had a terrible habit of talking very loudly, and despite his brother's

pleas to keep his voice down, absentmindedly he often lapsed into his old habit,

and then his guttural enunciations bounced like sponge balls off the walls of

the terraced houses that lined the streets of that area of Hammersmith.

On these occasions, John clapped his hands over his ears and ducked his head,

not that his brother's brogue was unbearable to him, but because an Irish accent

was not appreciated around those parts at that time, and John hoped that by

blocking and ducking he would avoid all consequences, as a little boy believes

that when he shuts his eyes, he can't be seen.

Outside John's lodgings they stopped and John fumbled in his pocket for a key,

while Michael began to whistle a jig.

"Shurrup!" roared his brother as thickly and sibilantly as he could.

"What's up?"

"For Christ's sake, stop whistling those stupid old tunes here on the street."

"Jesus, sure that's not an old tune, sure that's a new one."

"Well give over. See, you're not driving the ass down to the bog now, you know."

"Jesus, you have an awful memory. Sure I told you our bog was up ..."

"Right, up . ..! Jesus, it's awful," and John fumbled so hectically in his

pocket that he ripped the linings.

"See, the best thing to do when you're here," John advised, "is do the same as

everyone else. Don't act like as if you were over there. Know what I mean?"

"Oh, yea, yea, sound, sound!"

"Yes." He opened the door gently and whispered to his brother. "You stay here

while I make it right with the landlady. Right?"

"Stay here? Can't I come in with you?"

"No, you wait here. I'll make it right with her and then I'll come out for you.

Okay?"

"Yea, right, right. Don't be long, will you?"

"No, I won't be long, wait here."

Without hesitation, the landlady accepted John's brother as a lodger on

condition that they shared the same bed, to which John immediately agreed. He

came out and beckoned Michael.

"Right, come in. Don't make any noise whatever you do. If you as much as sneeze,

she'll be on to you like a ... She's a bit of an old bitch, you know."

"Jesus, is she that bad?"

"Shush! Come on."

They crept upstairs, John first.

"No supper?" Michael asked.

"Shush! No, no supper."

"Jesus, sure a man'd starve without a supper."

"Shush, give over! No supper here. You have your dinner in the evening and

that's it."

"Jesus! Now, I bet if she was Irish, we'd have a supper. Maybe she'd make one,

hah?"

"Isn't the old bitch Irish. Sure some of them are the world's worst."

"They are?" Michael exclaimed as he groped in the dark in an attempt to follow

his brother. "Jesus, you wouldn't think they would."

John sniggered cynically. "Ah, you've a lot to learn, yet about Irish and that."

"No light?"

"No, and don't talk so loud."

Michael remained quiet after that. He pulled off his clothes, groped for the bed

and dragged himself into it. Scarcely had his head touched the pillow when he

was fast asleep. He didn't hear his brother come to bed.

Michael (Mick) Weaver (Bolton)

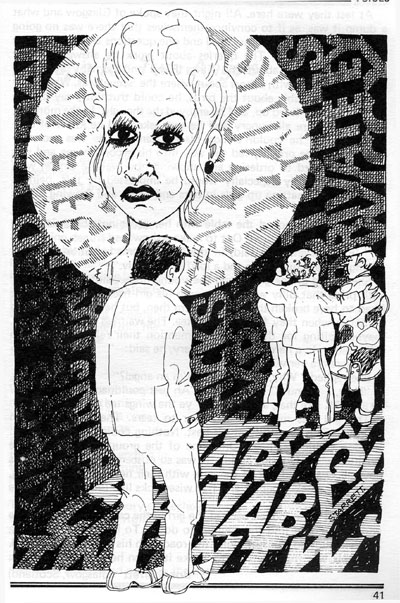

Ode to a Politician

Or Are Extramarital Relationships Dangerous for the Older

Man?

We have to meet in secret, it's always been the same

For not a breath of scandal must ever touch your name

You tell me that you love me but that's not true I fear

Your one love is advancement in your political career

You must preserve your image, the world must never see

You out in public places with a nobody like me.

You're always making headlines, your name's a household word

So you must be above reproach which makes it sound absurd

That tomorrow I will share your fame

Of that there is no doubt

For tonight whilst in our act of love

Your heart has given out!

Cindy Daley

Transformation

Me breddas dem ah dread,

While I an I stay crazy ball-head.

Dem likes fe shuffle dem feet,

An move to de reggae beat.

While I an I stay cool.

All I man check wid is school.

Me beddas dem ah laaf,

An ah say I man musy daft.

But I an I know de rule,

Me affe stay in school.

An when time comes fe leave,

Me breddas look pan me wid disbelief.

I come out dere wid three A's an five O's,

Ya know, I man really 'ave something to show.

But I an I can't get a job.

Dem tell me,

"It's not the colour of your skin,

It's just the situation that this country is in."

Now I an I turn dread

No more crazy ball-head.

Now I an I shuffle I feet.

At least now

I get something to eat.

Bev Shaw

(Commonplace Workshop, London)

The Harvester

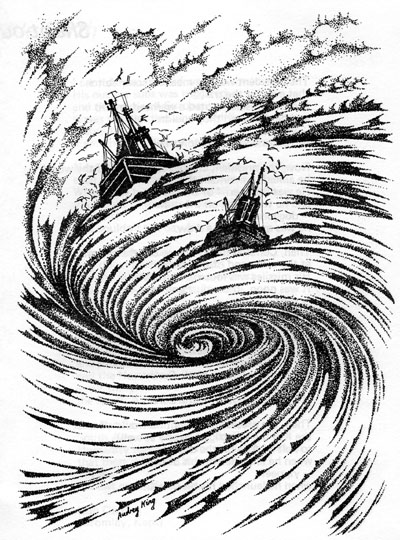

I was thinking of my father

As I stood aside the lock

And looked far away out to sea

To the lighthouse and the rock

My eyes they met the rolling waves

And focused white frothed foam

I heard echoes from

the off shore breeze

Pray bring my father home

He'd sailed about a week ago

Wi' his trawler, A wont say the name

To bring the silver harvest

To this Port of fishing fame

Its a rough life, he'd tell me

I took his words as bond

The rising storms and turbulent seas

With fishing grounds beyond

I was thinking of my father

Fish and what it cost

When I got the message

Gone down

All hands lost

Yes I was thinking of my father

Fish and what it cost

Alf Money

(Grimsby)

Agitpoem No 32

Shoot-out on Little Earth

The president was the meanest sonofabitch

that ever hit the trail

and the president toted a warhead or two

and he reckoned they couldn't fail

yes sir!

he reckoned they couldn't fail.

Now, the president clinked to one end of the world,

he aimed to maintain the law.

He was the sheriff of the capitalist west

and he was quick on the draw

doggone!

he was quick on the draw.

Then, Commie the Kid came out the saloon

at the other end of the street.

His missiles was loose in his holster.

It was noon, in the dust and heat

yep!

it was noon, in the dust and heat.

The president had sworn he'd make first strike

and he guessed he knew its worth,

so he told the Kid to reach for the clouds

at the shoot-out on Little Earth

gee whiz!

at the shoot-out on Little Earth.

Then, the president thought he wouldn't trust

the Kid (he was trigger-happy as well)

so half of Asia bit the dust

when he launched his bit of hell

yippee!

when he launched his bit of hell.

I can tell you the Kid wasn't slow to reply.

His nuclear subs was triggered

and the whole of Europe went up in flames.

It was more or less what he'd figgered

sure thing!

it was, more or less, what he'd figgered.

Next, the president loosed his projectiles,

each from an underground launching site.

When they hit their pre-planned targets

you couldn't tell day from night

no sir!

you couldn't tell day from night.

It was empty saddles in the old corral

way down to the middle east

and the fall-out lay thick on Africa

and the fire-storms never ceased

no sir!

the fire-storms never ceased.

But before radiation reached his bones

the Kid had some time on his side

and his pre-aimed rockets found their marks

and the North Americans died

sur thing!

the North Americans died.

The Pacific Ocean seethed that day.

South America waited for death.

Humanity was headed for the last round-up

that there'd be on Little Earth

yes sir!

the last on Little Earth.

Bob Dixon

(Bromley, Kent)

Maker

(For My Grandfather)

The bent nails that you straightened

were stored in hand-made boxes

of beaten aluminium,

cold to touch. A useful smell

rose out of dark, dank corners,

where feelings could congregate.

Maggie scraped the potatoes

as you struck the bright metal

into heels and soles, nursing

each nail between careful lips.

A handy world, where objects

would find their missing partners

and become whole: "It'll come in

handy". And it always did.

I have the last you used, with

the words 'Blakey's-Registered'

in cast-iron on the side.

A rough, uneven surface,

and rusted where boots would rest,

it feels strange and alien

as I balance its cold weight

here, inside this unskilled hand.

Terence Kelly

(Jarrow, Tyne and Wear)

Granny

Granny lived in one room

in a grimy back-to-back

with a bed, table and comfy chair.

Gas light poked it eerie finger

into every rancid corner,

and two ugly brown clogs,

which had gone to pot

guarded the Yorkshire range.

She had a garden

with rows of broken flags,

a full-grown outside lavatory,

and a flourishing midden top,

upon which tatty cats perched

and sang for boots and

a little water.

When she was old

and could not walk

she did not want to leave

her nightmare paradise

and live with us

in our sunny spacious house

with slippery bathroom,

silent fish,

flower-fertile garden

and electric this and that.

But she did

and died after seven belligerent years.

R. J. Pickles

(Bradford)

Witches

Once a week, when I was nine,

I went to an isolated hut

on the outskirts of a woollen town.

I dressed in green and became important,

because my uniform changed me

from snivelling education fodder into Superman.

The wind whistled through the walls

as we wrapped ropes round each other

and tied incomprehensible knots.

Sometimes we went outside to play,

each with his green and gold cap

firmly clamped on his boyish head.

The clouds raced by

and boys chased them

like demented mountain goats,

and shouted in terrified glee.

I was frightened by the bleak moors

and the deep brown quarry nearby.

I wanted to float away on the wind.

Suddenly our leader would call us

and make us crouch in a circle

and cry like moorland birds into the biting air,

'Dib, dib, dib,' and other incantations

and that was my only experience of witches.

R. J. Pickles

(Bradford)

Freedom

Sing little bird in your cage

You and I are so alike,

Bounded by four walls

Longing to be free

But even if the door was opened

Could either of us flee?

Iris Warburton (Liverpool 8 Writer's Workshop)

A Housepainter Remembers

His Swinging London

The outlook seemed a lot brighter for the young housepainter as he read

the letter he had just received from his native Glasgow. He was like many before

him, trying to 'make it' as it's called, in London. He had arrived in the Big

Smoke a few months before, and his confidence and youthful optimism was by now a

bit tattered and shop-soiled. London was just too big for him and he knew it.

The papers were full of the Swinging London thing. Lord Do-Nothing was opening a

disco somewhere and Lady Do-Nothing was modelling short skirts for some

jumped-up Cockney with a camera. It was all 'happening' the newspaper said. If

it was, it wasn't happening to him, so he had written to his mates suggesting

that they join him. The old strength in numbers story. He painted a rosy picture

and as his mates read the same papers, they couldn't get south quick enough to

get their share and so they had written confirming that they would be arriving

soon.

He looked again and again at the scribble across the sheet of paper to make

doubly sure that his eyes weren't tricking him. It was true alright his mates

were coming to join him. He couldn't relax for a second. He was too busy

day-dreaming about what it would be like with his fellow Glaswegians. He

wouldn't be so provincial now. One of the gang had been away from home hundreds

of times before, a bit of a tearaway. He was a gifted patter merchant and could

get all kinds of birds with his persuasive tongue, it was said. He put the

letter carefully on the bedside table to be re-read later, in case he had missed

something the previous twenty times. "Look out London!" he nearly said out loud,

as he switched off the light.

In the morning he went as always to the nearby cafe and got his usual slice of

toast and mug of tea. It was by no means part of the swinging London scene, and

wasn't the cleanest place in the world either, but he felt he could hide away in

the drabness of the place. He could relax here among the rest of the customers

who in the main, were like him, in rooming houses and kept themselves very much

to themselves. He soon discovered the reason for the large sale of newspapers in

the Capital. It wasn't primarily for reading, but for something to be propped up

in front of the silent eaters to tell others to keep their distance. He always

sat at the same table - the one furthest away from the glare of the neon strip,

above the serving counter and ate in silence, pretending to read the

advertisements surrounding him. He read them every day and knew them word

perfect. "Things go better with ..."

He was interrupted by the girl who worked there speaking to him. He waved her to

take the seat facing him, guessing correctly that was what she had said to him.

He was thrown out of his stride and had difficulty in communicating at first.

But the girl had long since lost count of the customers she had seen in her time

just like him. She knew his story by heart. Another northerner seduced by the

myths of the media. He looked at her pale smiling face that hadn't seen too much

sunshine and at the dark greenish, black rings under her eyes where the brutal

neon strip cast its shadows. Her most outstanding feature was her superb Roman

nose hooked, yes but not entirely ugly. She was friendly and indicated by a

sign that she wasn't hungry and promptly put her slices of toast in front of

him.

He mumbled his thanks and proceeded to dispose of them quickly. He was painting

on the nearby building site and had a formidable appetite. She repeated the

gesture every morning and he began to feel more optimistic. She fancied him

that was clear but he wasn't in a position to show his feelings. Not yet

anyway. Maybe when the rest of the boys got here and some of their confidence

rubbed off on him, he'd be in better form. But not now. So he never let his

feelings be known to the girl. He thought of her giving him the toast and how it

would impress his mates. Aye, even Billy, who had been around himself.

More and more he thought of her during the days he painted and he was amazed to

find her large nose was getting smaller daily. He was no stranger to the saying

that love is blind, but having never been in that condition, and not knowing if

he was in it now, he didn't want to think too hard about his position. But one

thing was certain he liked her more than he'd admit to anyone.

Only a few days more and the rest of the team would be here. He was looking

forward to taking them into the cafe and having them witness the performance

with the tea and toast. That would show them. If he could make contact with a

real Londoner, and a girl at that, all by himself, what could they accomplish

together? Another thing played on his mind. He hoped that they would find her

attractive without the toast being considered in the valuation.

At last they were here. All night they spoke of Glasgow and what a dump it was,

as if to convince themselves that there was no going back. They asked him a

thousand and one questions and he loved the role he was cast in. The queries

about work he answered easily enough. The ones about the Kings Road and Carnaby

Street, he replied as he did with others about where the 'scene' was. When they

asked the inevitable about the birds, he could truthfully say that he had got

himself fixed up, and he enjoyed the thought. In the morning, when they were all

hungry and he was asked did he know of anywhere to eat, he couldn't hide his

excitement. He was secretly delighted, as he proudly led the way into his second

home and was looking forward to ordering and showing how well he got on with the

waitress. Billy especially would be impressed by this, being a great one for

chatting up girls in bars and cafes, and showing off his wit.

The girl approached the table with her order note-book in hand. Billy was up in

an instant. Out to make a show.

" 'Ello, alright," he said, in the Glaswegian's imitation cockney. "Bring up

five cups of tea and a load of toast luv."

She smiled at the group and the young housepainter was bursting with pride that

Billy was flirting with his girl-friend. He would have liked to have broken the

news to them then, but he thought it would be better when they finished their

tea. The waitress was still smiling, maybe waiting for the painter to mention

their relationship, when Billy said it. In a hard Glasgow delivery, he said:

"Where are yer wings dear?"

She replied,

"Why, do you think I'm an angel?"

"Naw, I do nut!" he retorted. "Ah just couldnae see them giein' ye a BEAK like

that, and no' giein' ye the wings tae go wi' it!"

The girl was mortified and near to tears. The boys roared in approval. This was

Billy at his best. Nothing could stop them now. London would be theirs. Only one

of the group didn't join in the laughter he felt sick inside. It was so

obscenely cruel. The Scots boys all swaggered out of the cafe with their new

found confidence. If they all stuck together and had wisecracks like this, they

could be unbeatable.

None of them looked back at the girl in the cafe doorway, but one wished he

could find the courage to do so. To his shame, he didn't, and he followed the

rest along the road with his heart heavy as lead.

If this was the only way to 'make it', then he couldn't care less.

Bob Starrett (Glasgow, Scotland)

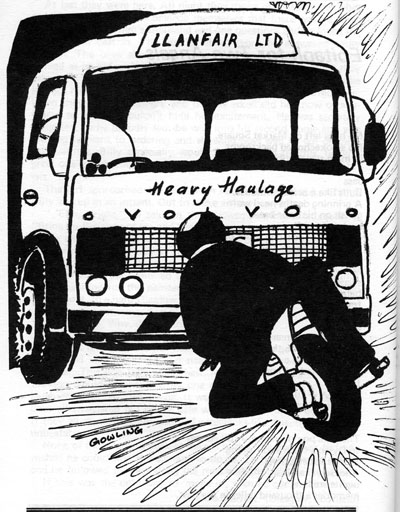

Epitaph for Two Angels

No hogs left on Market Square.

No smokechoked backrooms

in main street pubs.

Jess

Built like a brick shithouse.

A grinning deaths-head worn

garish on his door-bread

back, with a flaring

black beard bristling brillo pad

defiance at those who feared

his differences.

Miners blue tattoos screaming

swastikas and hate from his

bared on purpose

forearms.

Jess

Wrestling a train and laughing

as it carried him the first

hundred yards on his own,

long awaited, ultimate

trip.

His days of running ending in

the pain of brain burning

meningitis.

The juke box of memory still echoes

to Dylan's truth and Rolling

Stones Satisfaction.

And San-Franciscan

nights are long

memories a thousand miles in the past.

As dead now as

Felix.

The whip-thin weapon with nine lives.

Each gambled gleefully on Lifes

Dangerous Corners. Cashing in

his last under the wheels of

a Welsh bound Artic.

Signing out his life in blood and bone

on the tarmaced river of the Menai

Straits Bridge.

His Beachboy dreams of T'Birds

drifting smoky from his dying brain.

Felix.

Living out his grinning life

in the shadowed wings of a

lost Youth Rebellion.

Now the wine bottle stands empty.

The chapter scattered.

Dylan's truth echo's

in wiser heads.

No Stones.

No Felix.

No Jess.

No hogs left on Market Square.

Mick Hogan

(Wigan Leigh)

Luck

On the building site at mid day.

We sat round a packing case

And played cards while the tea brewed.

Paddy and Tiny White and Neverfuck and me.

We laid down the cards, one by one,

Each card a day's life.

And tight in our hands we held the rest of our days.

Red days and black days were scattered on the box.

Put down softly or carelessly or with a bang:

And Paddy is crushed between a truck and a wall,

And Tiny White is unemployed and bitter.

And Neverfuck a sour wizened old husk.

And I have smooth hands and a soft job,

For so the cards were dealt and so they fell.

Perhaps with luck it could have been quite different:

Paddy happily drunk in a pub in Sligo,

Tiny in a suit taking home real money,

Neverfuck happy in some peculiar way,

And for myself no need to feel a traitor.

That is how I would have dealt the cards

If I had known and if it had been my deal.

But these are the cards, smeared with thumb marks,

Torn corners, hard used every day.

Like Paddy, Tiny, Neverfuck and me.

And this is the game, and this is the building site,

And these are the dirty times we live in,

And if we are going to change our luck and win

This is where we must start.

J. Clifford

(Birkenhead, Merseyside)

Bomb Site

Hidden behind the hoardings

From genteel shoppers' eyes

But open to the council houses;

The filthy bomb site lies

Over this acre of jumbled rubble

The tatty-headed thistles rise.

On the rusty wire, the chaffinch

Surveys his private paradise.

Edgbaston Reservoir

Soaring serenely over slums and villas

The Kestrel carefully scanned the ground,

Till he reached the trees by the reservoir

Where magpies rose like a mist to meet him.

Like mad things they mobbed the murderer.

Climbing and diving, like spits on a Heinkel

Their caws and claws weaving a deadly quadrille

At which the wind walker wavered

And fled

Plummeting down like lead.

Flying fast and low over the water

The luckless hunter fled the slaughter

Gulls now ringing his head.

Richard McCartney

(Birmingham)

Kids

You work all day

And evening too

To keep them fed and clothed.

Mummy, daddy, I want this,

I want that one too.

You shorten the rent to provide

But they don't care to thank you.

They are sixteen now

And you need help.

But will they help you?

No, they are leaving home this Easter.

Sylvia St. Luce

(Peckham Poets)

Long Black Overcoat

It had been a week since Billy had first spotted the long black overcoat;

lording it in the junk shop window, strung up above the heaps of yellowing

books, piles of broken records and a multitude of assorted rags and junk. The

tail end of a freezing December blustered about the emptying streets. People

scurried to and fro swaddled in scarves and collars, their noses pressed to the

ground like so many tracker dogs hunting out the warmth of pub or home.

Billy, having no collar in which to swaddle his nose, was tormented by the sight

of the coat as he passed each day to and from work, with only a short woollen

zipper to protect him from the sharp lick of the wind, and barely the price of

his fares and food to cheer his pockets.

And now, blustery and bitter with its streamers, balloons and holly, its forced

cheeriness, and the sharp tang of drink coming in quick successive blasts from

the swing doors of crowded pubs, Christmas had at last arrived. Billy hesitated,

dominated by the coat strung up on the other side of the glass. He was two weeks

wages: ninety pound the richer; yet still he was reluctant to push inside.

Eventually torn between what he guiltily felt was extravagance and his own good

sense, he entered the shop.

A wall of suffocating heat was thrown up by a battery of oil heaters scattered

around the shop, yet Billy still shivered against the wind rattling at the door.

He stood for a while, peering through the gloom as if allowing his eyes a browse

among the heaps of assorted junk; a huge mountain of stuff tipped and scattered

all about the place.

Embarrassed at being in such a shop in the first place and feeling about as

vulnerable as a pauper in paradise, Billy shuffled towards the owner; a man who

bore a striking resemblance to a ferret, beavering away among his pile of rags.

"How much for the coat," Billy asked, pointing.

The junk man had sized him up at a glance when he had first entered the shop.

Poor? Yes of course! Summer clothed in December marked him as that. But

destitute? No, far from it. He would have money, not much, but enough. The junk

man ran his long thin fingers lightly along the sleeves of the coat, up and

down, as he spoke:

"Its a good bit of gear, son! Used to top a collar and tie this is, belonged to

an office waller, didn't it! But then you can see that for yourself, can't you

son."

He paused looking slyly up at Billy, now more than ever like a ferret;

"More money than sense getting rid of a good bit of gear like this, and he

didn't give it away either, son."

Billy ran a glance over the coat. At close quarters it looked worn and

threadbare, more used to flaunting the by-ways of Euston that the ordered

elegance of the City. Yet the longer and closer that Billy inspected the shabby

garment, the more committed he felt to actually buying it. Not that he didn't

need it, shabby or not.

"How much?" Billy repeated.

By now as the result of a few deft manoeuvres on the part of the junk man, Billy

had the coat draped across his arm as if he owned it already. However the junk

man wasn't ready yet to commit himself to a price.

"You know what son? If this shop was better situated, I could ask fifteen maybe

even twenty nicker for a coat like this."

He watched Billy carefully as he spoke and noticed a slight drop in his

expression. He moved in quick, almost in panic:

"But here, right here and now, well I'd say, em, give me a tenner. Yes son, a

tenner would be fair, very fair indeed, son."

Billy swapped the coat from one arm to the other. The junk man thinking that

Billy was refusing the coat, pounced:

"Its worth twice that;" he insisted, forcing the coat back onto Billy

challenging him to deny its worth. Billy muttered something to himself offering

the coat back. Not actually refusing it but merely passing it back in confusion.

The junk man raised his hands effectively blocking the coat;

"I know I could get more. Of course I could. But still, ten I said, so ten I'll

take. I did say ten, didn't I."

Billy nodded approval.

"Well, if I say ten, then ten it is; I'm nothing but a man of my word, son."

By now Billy was beginning to panic. He felt both confused and committed to

buying the coat. Suddenly he realised a hundred and one things of more pressing

need to himself and his family than the luxury of a rotten coat he could ill

afford. Yet he already had the coat. He was practically wearing the damn thing.

He felt in his pocket for his money, conscious of the junk man's yellowing

ferret eyes watching his every move and expression.

"Perhaps you would take something in part exchange," Billy asked, as he

desperately rummaged around in his mind for what saleable item he possessed,

small enough to be sneaked away from the house.

"Perhaps a radio or something" he asked.

The junk man hovered in despair. He arced his arms to take in formidable mounds

of junk.

"Look at it," he accused; "Junk, junk, junk. Everywhere I look piles of bloody

junk. This place is locked solid with it. Its the same every Christmas;

everyone from miles around treks here to flog me their rubbish. Do you think I

need it?" He demanded; "Like a black eye I do. But I buy it. Like a fool every