|

ISSUE 23

cover size 210 x 148 mm (A5)

EDITORIAL

At a time when more women than ever are writing - or owning up to it - we

decided at the last editorial meeting to see how many women were in print in

issue 23. We found a ratio of one woman poet to eleven men, and two women

short-story writers to four men.

One of the most obvious reasons for this conspicuous absence of women's work is

that fewer women send contributions to VOICES. Which is strange, because the

worker-writer movement can boast a community rich in race, generation and

gender. It must be the same old story: women are backward in coming forward. But

there's another reason. During this discussion, a man made the comment that, ".

. . women's work tends to be more of the same . . . intense stuff." Reading

between the lines, could he really have meant that women's work is obsessive?

And if so, doesn't that mean our compulsion to write is therapeutic?

Uncomfortable, isn't it, because it's not so far away from the by now famous

remark made about Federation writing as, ". . . successful in a social and

therapeutic way, but not by literary standards."

They say that the pen is mightier than the sword, but it's a long time since

Boadicea's lot carried swords around. And if carrying swords is a symbol of

power, then it was men who were traditionally invested with authority by the

sword. And so it still is with the pen. Bourgeois writing is dominated by men,

and in setting up alternatives, the worker-writer movement still has a long way

to go. For some women writers, only the accent has changed.

There's still a strong feeling that men's writing is the Norm; and in my

experience at Commonword workshop in Manchester, this attitude causes problems.

It's a city-centre workshop, with a membership of three men to every woman. Real

attendance is almost exclusively male. When women do make an appearance, they

rarely, if ever, return. What is obviously an ordinary workshop discussion to

the men, feels like aggression to some women. The women who do cope, whose work

I would describe as 'broad' in its approach and subject matter, fit into the

workshop because their work resembles the men's. Everyone feels at home

discussing their writing. For the woman whose work is feminist, who writes about

her personal life, it can be a rough ride. If she manages to overcome her

inhibitions enough to reveal the intimacy of her writing, it is quickly felt to

be 'different.' The workshop is restless, uncomfortable.

Recognising these problems, a women-only workshop was started a year ago. It is

based in a suburban library in a well-lit area. In the familiar company of other

women, writers gradually build up their confidence. And whilst it is not

exclusively a feminist workshop, it is probably the feminist writers who gain

most. They need reassurance that their experience of the world as women is

shared by other women. Whilst men might be able to criticise the form of their

writing, the crux of the matter is that they cannot share the same experience of

the world at the personal level. After a successful year of separation, the two

workshops are now paying court to each other. Women from Home Truths workshop

are not only publishing their work in Commonword's magazine, WRITE ON, but they

are now working on their own publication. And the are accepting invitations to

'visit' Commonword.

I can only speak with certainty about Commonword, but the pattern found here

might be repeated elsewhere. A women-only workshop is a reminder that the world

of men's writing is not complete. Where are all the stories written by men about

relationships with their children, wives and lovers? Where are the descriptions

of their places in the pecking-order? How does it feel to live in a man's world?

Of course, some men do write about these things, but they are the exceptions

which prove the rule, and their work rarely sees the light of day. If feminist

writing is 'only internal', then men's is 'external.'

In their 1978 anthology, WRITING, Ken Worpole and others wrote on behalf of the

Federation, "Working class writing is the literature of the controlled and

exploited. It is shot through with a different kind of consciousness from

bourgeois writing. Whatever its subject matter, working class writing . . . must

.exude through its tissues, working class experience. Politically, the class

struggle would be felt . . . even if the writer has not such designs on the

reader." Feminist writers are not exempt from exploitation, but because their

work deals with only one aspect of it, there's the feeling that they are troops

AWOL from the true front line of class struggle. Some feminist writers would

not, of course, describe themselves as socialist-feminists: any more than all

working class writers would feel that they belonged to the worker-writer

movement. I was present at the women's writing conference held in Birmingham in

May '80. There were at least as many women there as Federation members at the

AGM in Nottingham, April '80. The first women-only workshop has applied to join

the Federation, and there will be more. The worker-writer movement needs

commitment from feminist writers: I believe that the editorial page of VOICES is

as good a place as any to examine our commitment to them.

If socialism is, ". . . rooted in a love of life," it might seem strange to

define feminist writing, full of resentment at times, as basically socialist.

But it is written in the very language of vitality: feminist anger is the out

and out denial of defeat. Theirs is the vocabulary of defiance. The message

might seem personal, but the bone is pointing at the common enemy.

Wendy Whitfield

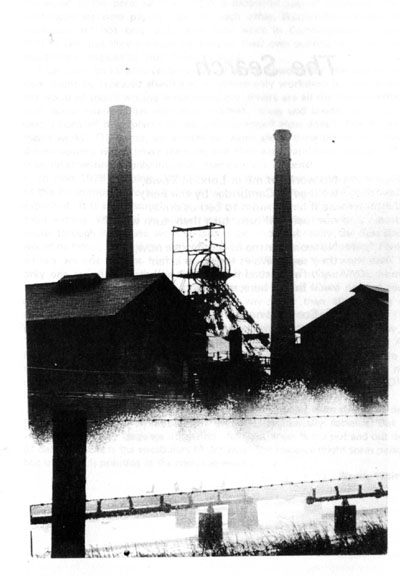

THE SEARCH

No work for me in London Town,

we'll go to Cambridge by the Fen;

we'll hire a room to bed us down

our luck will turn, turn then, turn when?

No work for me in Cambridge now,

they say in Wales the wage is fair

we'll find a road where luck will grow,

we'll find it here, we'll find it there.

Oh Scotland now is far away

and has no work in isle or glen;

we'll find a home to stop and stay,

our luck will turn, turn then, turn when?

Ralph Meredith

(Haworth, Yorkshire)

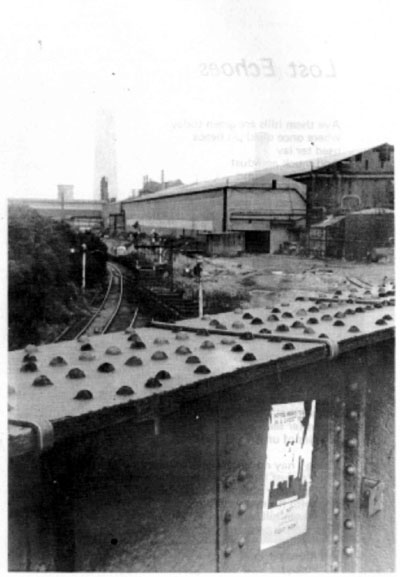

LOST ECHOES

Aye them hills are green today

where once owld pit heaps

used ter lay

And muck and dust

with stone abound

rushed down from top

and choked the ground

of all its summer colour

The belching smoke a remember well

from tall pit chimney

used ter smell

and fill the sky

with grime and smog

While down in't Street

it used ter clog

us all in't throat and chest

O'er yonder tall wheels

used ter creak and groan

There's nowt there now

it all as gone

and all that's left

for us ter see is miles of unspoiled greenery

There's nay noise of works or shunting train

They're just lost echoes, down yon winding lane

Where weary miner used ter walk

and with his marra used ter talk

Aye them hills are green today

Still owld memories nivver fade away

ALf Money

(Grimsby)

REDUNDANT

I was part of her once

yon Trawler, that stands in line

with the rest of her clan

that bob and sway

restless, all fast and tight

like shackled spectres

in the grey cold morning light

deck, galley, wheelhouse

and off shore breeze

are cluttered with older memories

rusting winches no longer turn

nor white foamed seas

surge bow or stern

or laden nets spew out

their silver harvest

from fathoms deep

all lie redundant now

in endless sleep

beyond the lock and gate

and wait, and wait

for oblivion

in the breakers yard

while I

slowly, pass them by

and think of another

bleak tomorrow

Alf Money

(Grimsby)

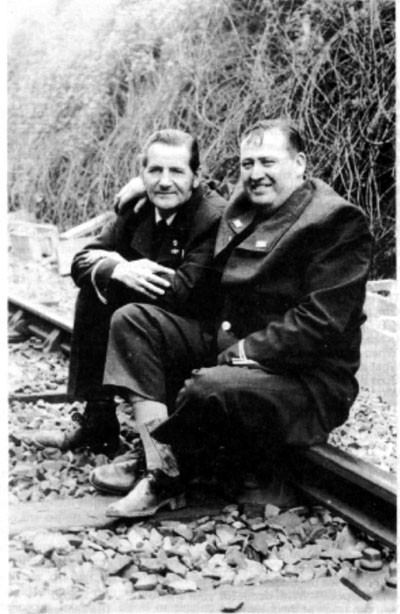

PHOTOGRAPHS

I have seen you before somewhere;

Were you not third from the left

In that faded photograph,

Among the others in khaki

Or stiff in suits and cloth caps?

And did you not die on the barbed wire,

Or deep in the mine, or deep in the workhouse,

Or in some long forgotten rebellion,

B rave when others were brave?

I cannot remember.

Yet I have seen you before

Many, many times;

In the pub, on the picket line,

The dole queue, the supermarket,

The works outing.

And not just here either.

Did you not march out one winter morning

And dig trenches to defend Moscow?

And did you not ride the boxcars

Into Oregon through the rain?

And did you not picnic one spring day

In your sunday trousers on the banks of the Seine?

Friend, your name is lost for ever, and yet

Any mirror will tell me

Where I have seen you before!

J. Clifford

(Birkenhead)

LIVERPOOL HUMOUR

It is time somebody told the truth,

The whole truth,

About Liverpool;

Or at least tried to.

Remember -'Every silver lining has a dark cloud'.

Here is your Liverpool Optimist

He still reads Liverpool Poets.

Here is your Liverpool Poet

He'd rather be a comedian.

Here is your Liverpool Comic

'He can't fight so he wears a big hat.'

There must be more to Liverpool

Than a story

Of a bevvied docker

Kicking a tortoise

In the ghost of Scotty Road.

'When one door shuts, another closes.'

What about those posh suburbs

Does Blundellsands talk to the Dingle?

What about all those scuffers

'He got his injuries, Me Lord,

Falling drunk

Down the police station stairs'.

How thick the bullshit falls!

'Have a care

Mister Mayor

There are people

Down there'.

Ten miles of dying docks

Glow in the sunset

Look beautiful from Birkenhead

From the 'One eyed City'

You can't see the dockers.

Ah Liverpool - 'With death for your friend

You can laugh at shadows.'

J. Clifford (Birkenhead)

KIPPORS

In the year of umpteen thingummygig, just afore the Great Plague swept the

country, things wor a bit bad for work in Newcassel. Seh Jimmy Jenkins whe came

from Pandon Dene decided teh gan teh London teh seek work theor. Why taalk aboot

jumping from the frying pan inteh the fire. He was ne sooner theor than folk

began teh drop like flees. Wi a grim touch o humour Jimmy says, "Thor'll be

plenty o jobs noo," but in this he was to be proved wrang. He had been existing

on handoots from a charity which it seemed allocated the jobs as weel. The best

jobs went to the locals. Jimmy had his hopes of becoming a professor or a brain

surgeon dashed by the clerk behind the coonter o what must hey been the

forerunner o today's dole.

"Ah've just the job for ye, Geordie lad," he says. "Ye 'knaa folks is dropping

like flees wi this plague. Somebody's got teh born aaIl the bodies and yore the

forst applicant the day." What he didn't tell Jimmy was that thor was a football

crood behind the door waiting till the post was filled.

"Beggar that," says Jimmy. "Ah didn't come heor teh work in a crematorium."

"Ye've ne skill," says the clerk. Here he smiled sweetly. "If ye diwen't tek it

Ah'll hey ne other choice but teh stop yore charity."

"Aall reet," says Jimmy, "Ah'll tek it, but under protest, mind."

Seh Jimmy reported teh the crematorium for duty. Mind, what a grey and gloomy

place it was. The greet fires which nivvor went oot gave off a lurid glow which

cast shadders roond the room. Thor leet fell on the makeshift boxes which

contained the bodies and on the bodies which had ne boxes. As fast as bodies wor

shovelled in inteh the fire others tuek thor places. Jimmy, dripping wi sweat,

thowt teh hissel, "Why, if Ah'm still heor when winter comes, Ah'll be luvly and

warm."

Noo after Jimmy had been theor a few weeks, he managed teh get a letter off teh

his mother saying hoo food was in short supply. Could she send him summat doon?

He had visions o such Tyneside delicacies as stony cakes or singing hinnies.

Hooivvor, his mother demonstrated hor practicality by sending him a pair o North

Shields kippors. Travelling by coach, it might be said that on arrival they wor

a "stage" or seh removed from being fresh. Nivvor mind, Jimmy reckoned that even

if he deed he was ganna eat them kippors. Hooivvor, not ownly his eyes had seen

the arrival o the parcel, and on opening what it contained Jimmy slunk away

warily teh the fornace, theor teh toast his feast.

He needn't hey worried. Nobody was ganna touch him or his kippors. Not yet the

woren't. They wad wait until they wor cooked. That moment arrived, Jimmy

retreated, walking backward teh a table on which an open coffin box stood. As he

sat on the edge of it, then the clamour grew. His mates closed in from aaIl

sides. He used his feet teh fend them off while howlding the plate behind his

head. A gleeful voice cried, "Kippors!" and a thin wasted hand reached oot o the

coffin. The kippors disappeared inteh the box. Jimmy and his mates listened

spellboond teh the munching soond emitting from therein. Thor was a lood belch,

and a voice says, "Ta."

A few minutes later, when Jimmy and his mates plucked up courage teh luek inside

the box, thor was ownly a deed man theor. On his arm hooivvor was a tattoo which

bore the legend, "Tyneside for lyvor". Jimmy wondered had a once familiar smell

revived a deed compatriot. Anyway, if his kippors had teh gan teh anyone but

hissel, it was as weel that they should gan teh a fellow Geordie as one o them

Londoners.

Dick Lowes

(Newcastle-upon-Tyne)

Local Call

1976 saw a great debate in Tower Hamlets over how a grant from Thames TV,

channelled through the Greater London Arts Association, should be spent. The

original idea was to plaster the area with the work of professional artists from

outside and generally to bring some kind of cultural meals on wheels to the

needy. Strong protests from within the community led to this idea being dropped

in favour of funding community-based ventures, both existing projects and new

initiatives, in the fields of music, drama, dance, photography and creative

writing. People from the Basement Writers were among the early beneficiaries of

this money, and they were later involved in setting up the THAP Bookshop. The

TOWER HAMLETS WORKER WRITERS GROUP was also set up when it was felt that there

was need for more than one group, and it meets above the book-shop in

Whitechapel, East London, So although the writers group is independent, links

with the main Tower Hamlets Arts Project are many.

NO DAWN IN POPLAR

When the sun comes up in the morning

rising slowly

the sun comes up

it's the sun coming up.

There's no dawn in Poplar.

Richard Brown

(Tower Hamlets)

BOY DANCER

I saw him there; amongst the frantic

Red, yellow, green, blue light

And the bodies like loose ropes flexed

In dizzy vigils of fun, and

Thought it strange that a boy

Broken spined, fixed upright

From supine - should want to hear

Those litanies begin, of beat

(vinyl unravelled tidily to insist)

But not be able to answer back

So uselessly sat, with fast eyes watching

And still flesh folded in a chair.

But he began to shove and jerk

That iron, to coax speed from wheels,

Roll back and forth and almost spilled

On leaning cogs, swinging circles on

Each metal step, both directions

Like a mad sprung clock - till

Wrung of motions, till head hung spent.

Stretching in the fashion, some turned away

To disdain in laughter what

They thought it meant

A foaming prayer, a mutant dream

But a virile mind had sought to be

In time with us and therefore, free;

So brought worship of the dance

To me.

Tony Marchant

(Tower Hamlets)

THANK YOU!

Trafalgar Square tube:

Nameless corridors tiled in white

Thick with early tourists on a Sunday in spring.

Coming up at last for air,

My ears catch the strains

Of Pan-like pipes in ecstasy,

And there he stands,

With upward steps to left and right,

Caught in a shaft of soft sunlight,

A shining silver flute at his lips,

A box at his feet,

Lined with a square of richly coloured silk.

As I pause in front of him,

Hand already on my wallet,

I see the box is empty.

I take my time.

Open the wallet,

Open the coin purse,

Select some silver,

Listening all the while to the music.

Two tens and two fives

I drop into the box,

Casually as I pass,

And as I do he takes the flute from his mouth.

"Thank you!" he says.

I nod, a little shyly,

Lost for words,

Head on up the steps,

As the music starts again.

London Transport's powers that be

Detest live music it seems to me:

With piped Max Bygraves they assail the workers

As they pass harassed through Oxford Circus.

Mark Haviland

(Tower Hamlets)

THE MOVERS

ONE

Sleep curtailed by the thick rude call of the horn, Tadpole leapt straight from

his bed. He had been laying in an expectant doze for a while, but when the blast

came it was as great a shock as ever. Tadpole had only just managed to pull on his trousers and oversize vest when the

horn sounded again, several times, and with a chorus of shouts and abuse to

accompany it. He pulled a shirt around himself and stumbled out the bedroom door. 'O.K., O.K.'

he called as he ran barefoot through the passage. He pulled open the front door.

'What you doin' of Tad? Get up here' came a voice.

Another voice: 'For Christ sake 'urry up shortarse. But get some bleedin'

clothes on first though. We won't see you otherwise Laughter.

'Sorry' shouted Tadpole 'I overslept. I'll be ready in a second, just give me-'.

But the voices were by then talking amongst themselves.

He finished dressing. More clothes than necessary really, but they were jumpers

and things which he could peel off as things got hotter during the day. He pulled on his boots and tied the laces quickly. 'Sod it'. What a time for a

lace to break. Warmer and repaired Tadpole just managed to yank the door open in time for a

last frustrated blare of horn.

'About time too' said a voice 'We were just about to go off without you'.

Tadpole hardly ever differentiated between the two voices, surprisingly, because

they didn't sound at all alike. Len's voice was deep and demanding, the turgid

sea of coughs, splutters and snorts of a burly, grey, yet not totally humourless

man in his fifties.

Mickey's voice however came out of his nose, a whine which broke out into a

chuckle. A couldn't care less, occasionally threatening, spotty, eighteen year

old voice. Tadpole was thirteen and nobody needed to ask him why he was called Tadpole. His

thin body, with the head that seemed just that bit too large, jumped into the

cab of the van beside Mickey. Len started the engine and threw the gears into a

heavy first. The lorry lurched away from Tadpoles front door, mum and dad still

fast asleep inside. They didn't have to be up until after eight.

It was a fresh morning. The side window was wound right down and Tadpole watched

his sleeve whipped by the wind back and forth on his wrist. The barely developed

arm and fist bristled back at him from the vans side mirror.

They stopped for petrol almost immediately. They all got out, Len to fill her

up, Mickey for a piss and Tadpole to once more admire the broad and bold

lettering on the vans side. L.M. STONES & Co. REMOVALS. 'The M stands for

Maverick' Len had once told him.

'Who did all those words on the side?' Tadpole asked Mickey.

'Dunno. Some bloke with a paint brush'.

'It's perfect. All the letters are perfect, must have been a real craftsman'. Mickey laughed. When they all got back in Tadpole was centre, the other two shouting frantically

over his head. It's more than just noise in the cab. It's teeth, tongue and

tonsils all jogging up and down, conspiring with the din to make whatever you

say unintelligible. They were talking grown up. Dirty.

'Look at her arse'.

'Where?'

'There'.

'Oh yea. Bet she don't go short. Bet she's a goer. Give 'er a wave'.

'Hey, she smiled'.

'Told you, must be a scrubber'.

It was still early morning when they pulled in for breakfast. That's the drill.

Get near to the load up point, have breakfast, then straight in the gaff

afterwards to hump everything into the van, lunch a bit later on the road,

unload and then off home.

'This cafe you reckon?'

'Yea, I reckon. We'll give it a try eh?'.

Morning was the time of day Tadpole liked best. The roads not yet choc-a-bloc

and the shopkeepers keys only just in the locks, breath visible out their

mouths. Mickey pushed open the cafe door, mornings forever after in Tadpoles

mind fused with the promise of frying bacon, popping eggs, exploding sausages,

sizzling tomatoes and of course the sniff of two fried slices. Then. the hiss of

the giant tea urn, the sudden burst of mighty steam. It was the nearest thing

Tadpole had seen to a real railway train. Monster mugs of tea for the workers.

Lots of sugar. Len never had less than three teas, he fuelled himself on the

stuff. There were flies treading the sugar in the bowl before them on the table. Tadpole

half expected to find rats in the salt, rhinoceros in the pepper.

It was a very tiny cafe that could have been a large cafe if they had got rid of

all the 'out of order' pinball machines. The curtains that protected the cafe

from the world had never been washed. Tadpole could tell that because he assumed

they had once been white. They were the only three in the cafe until the arrival of a spiky haired youth.

'Wotcha Luigi. I'll have the usual' he called out merrily.

'What's the usual' said Luigi, who wasn't Italian.

'I can't remember' said the boy, who was in the wrong cafe.

It was only a short drive to the house. The van snuck through the thin streets

of dockland, the sun obscured by high warehouse walls. The house was one of

those flat faced little two up and two downs that open straight out onto the

street.

'Stinks around here doesn't it Mickey' said Len 'I don't blame anyone for moving

away from here.'

'Bloody right' said Mickey 'Not as if it's really England round here these days

anyway. Know what I mean?'.

Len knocked on the chipped front door. It was answered by a boy of about five,

clean and smartly dressed. He looked up at Len wide eyed. A woman's voice:

'Rickie love. Who's that at the door? Must be the movers Rickie.

Go and tell your father Rickie'.

The boy trotted off obediently without saying a word. The three squeezed into

the thin passage, stacked high with boxes and crates full of the house's smaller

objects. Thirty, dark haired and chunky, he bounded down the stairs.

'Hello gents. Up bright and early. That's the way to make the money eh?'.

'That's right' said Len 'We like to get things rolling as soon as possible'.

'Coffee' offered the man. He scratched his chest, hairy beneath a fitted shirt

and gold medalion.

'No thanks, as I said, we'd like to get the van loaded up as soon as possible'.

'Sure thing, sure thing. You're the experts eh? Early bird catches the worm eh?'

'Is that the removal men dear' came the

woman's voice again. 'Do tell them to be

careful with my chaise-longue. Don't forget the money we had to have it

reupholstered. Tell them to be careful with that table too, that's real antique

you know?'. The man shot the movers a grin

'Don't worry about her lads, she worries she does

that girl'.

'Don't you worry love' he shouted up. 'These men are experts. They know their

job'.

Tadpole realised after just the few jobs that he had done with Len and Mickey

that packing the van was the most important part of the whole operation. It was

no good just slinging all the stuff in and ending up with a full lorry and half

a home full of gear to worry about. It's not a skill acquired overnight either.

It's mainly common sense, but that's not a sense that's particularly common,

thought Tadpole. The woman appeared. Bottle blonde and big.

'Looks like the foreman's arrived'

Mickey whispered down to Tadpole.

'Oh don't you worry about him Missus', said Mickey to the woman 'you're not

paying for him. We only bring skinny along now and again on his school 'olidays

to carry out the electric freezers'. She gave Mickey a funny look too. The man was giving Rickie piggy backs.

'Look at this place' he said to Len. 'All

this furniture is the best, know what I mean? We're only working people but I

always make sure we always get the best of everything. We've outgrown this place

of course. It's got the lot; damp, woodworm, mice and rot. And as for the area,

well we all know what's happened to that don't we?'.

'Oh yes mate' nodded Len. 'Oh yes'. He was humping out a sideboard on his back.

Tables, chairs, sofas, cupboards, beds, mattresses, carpets, stereo systems,

fridges, freezers, electric cookers, reproduction paintings, horse brasses,

little ornaments, knick knacks, dolls of Spanish ladies with light bulbs rammed

up their dresses - and a chaise-longue too -were all packed tightly into the

van.

They were already in the van with the engine revving when there was a thumping

on the cab door. Mickey flung it open. A small shabbily dressed Asian stood

waving a piece of card.

Mickey: 'You what Ram Jam - Oh yea - Where's that then? -Oh I dunno about that -

Why? Pressure of work mate, pressure of work'.

The Asian: 'Unintelligible.

'What was that all about Mickey?' asked Len as the Asian was shuffling off down

the road, Chaplinesque.

'Says he wants moving, tonight if you don't mind. Says he's being evicted and

he's moving just round the corner. Desperate, he reckons. That's the address

there on that piece of card he gave me'. He flung it down on the dashboard. 'I

should have told him where to stick it eh?'

They laughed. Tadpole thought it sounded the same way people laughed at him

sometimes. They were grown ups. They must be 'in the know'. He pretended to

laugh, but he didn't really get the joke. And they were off, back on the road and looking at girls' bums. The man, the woman and little Rickie pushed off the same time in a shiny new

saloon.

'We'll be there ages ahead of you in this pal' said the man. 'Doesn't matter

though does it? You know where it is don't you?'

'Thank god they do' thought Tadpole. When Len and Mickey didn't know the way the

clients sometimes had to squeeze in the cab while Tadpole had to sit in the

back. There were many times when Tadpole had suffered the experience, sometimes

with Mickey but mostly by himself. He could never get used to seating himself in

and amongst someone else's old furniture. The back doors would be shut and bolted

and darkness would reign for an awful minute until his eyes adjusted. It was

only when the load was very light that the top half of the swing doors could be

left swung open. Then he could see where they had just been and sniff the

exhaust deep up into his nostrils. It would seem an age back there even before

the engine shook and all hell, heaven and earth broke loose. The piled up and

neatly arranged furniture, so stable and still a moment before would begin

dancing and shifting. Tadpole would be flung up and down, sideways and inside

out. If only Len and Mickey could see him sitting there, straining like some

reverse Samson, arms outstretched holding up two pillars of swaying kitchen

chairs. But he wasn't in the back now and save for the risen sun making shapes on his

eyes everything was hunky dory.

'You could make a great T.V. series out of his job' said Mickey.

'Eh?' Len screwed his face up, coughed and wheezed a bit.

'Yea, you know, all the things that 'appen, all the foreigners and the jokers we

have to move about. Could be a riot'.

'Load of rubbish on telly nowadays, Len exclaimed.

'Yea, not 'alf' replied Mickey. 'How about that bloody thing they had on the

other week, two an' half hours of sodding ballet. Load of pouffs prancing about

in tights'.

'Right. Didn't have that in my day' nodded Len.

'Didn't have telly in your day' ventured Tadpole, his voice barely audible above

the motor.

'Exactly, only had wireless. Wouldn't have had all that ballet rubbish on the

wireless. Had too much dignity'.

Len put his foot to the floor and the van squeezed out of the lean streets, away

from the high walls and towards the motorway. A new house for someone,

somewhere, someplace out of sight. Tadpole cast his eye around the houses about

him. All houses must be pretty much the same he thought, just four walls and a

roof, a front door and a collection of furniture. He put such thoughts out of his head, settled down for the journey ahead. Time

to dream, time to rest his already aching limbs, time to not have to do

anything.

TWO

Before they reached the edge of the city and the long, thirsty motorway, Len

decided that it was time for another cuppa. Clean curtains at the windows, napkins on the tables and the menu wasn't written

on a blackboard in this one. A cafe nevertheless. It was dinner time by then so

chips and beans joined the sausages, egg and bacon. No fried slices but instead

buttered bread. No flies in the sugar. Some people talk sense, some don't, Len don't. No sin in itself Tadpole

supposed. Trouble with Len though was that he would talk it to everybody he met.

He would talk to anybody, anywhere, about anything. You know those old women - they carry old plastic bags around with them, maybe

have a few dogs on a lead, and they stop still in the middle of the street to

talk to imaginary people. Well, Len was talking to one of them. Sixty five with

white hair and a rat eaten old coat.

'Some bastards broke into my house the other week. Bastards. Pissed and shit all

over the place, ripped things up, messed things around.'

'Did they love? Did they? I know what it's like' comforted Len.

'Even if they had to nick things,' she carried on 'even if they had to nick

things, they didn't have to mess the place up'.

'I agree' Len nodded. 'That wouldn't have happened years ago. Not in my day. We

had decent burglars then'.

'Yes' echoed the old lady 'decent burglars'.

'In fact you could almost call them honest' he said 'it was just a job to them,

not a bloody vocation'.

Mickey looked at Tadpole and started to giggle. 'Just listen to all this old

twaddle' he whispered. -

Len never drank alcohol as a rule. After his fourth mug of tea however he seemed

to be in the exuberant chatty mood that most people experienced after a few

pints. He was soon jabbering uncontrollably to the old lady about the movers.

'Of course' he prattled on 'In my fathers day when he ran the business, the

furniture had to be shoved around on a handcart. Those were the bloody days. A

long move took an entire day from early morning to well into the night, might

have to make a few journeys see? Some firms had a couple of horses to pull the

cart, we did after a while too. I had older sisters but seeing as I was the only

son I took the business on when the old man died. I had three lorries at one

time a few years back and three teams to do the work. I'm down to one now

though. I just got fed up with all the form filling part of it. I like to know

what's happening and to do all the jobs myself.'

'Bastards' said the old lady. 'Bastards'.

Meal over. They rattled along the motorway. All the time the movers talked and

joked. Tadpole's eyes fixed thoughtfully on the tiny cars ahead and he listened

to the tales of the road, the silly, loony, sad, rude anecdotes that Len had

told for years and made better over the years. Mickey chortled along and

sometimes tried to match one of Len's stories.

Out through Essex and easing off the motorway they entered the new town. They

cruised slowly looking for the correct street, a detailed little hand-drawn map

on the inside of a fag packet their only guide.

'This is it' shouted Mickey triumphant 'Letsbe Avenue' (that wasn't it's real

name of course). They edged along the crisp surface of the road, high, taut

trees to either side. They saw the shiny new car outside surveying their pastures

green (the name of the house was 'Pastures Green').

'What do you think of it then eh? asked the man, little Rickie framed between

his legs.

'Very nice' said Len without emotion. 'Very nice. What will you do for work

around this way then? His eyebrows knitted.

'I'll be travelling down to London in the car everyday' the man answered.

'Cost a bit, won't it?'

'Oh yea, course. But I'm not short of the readies. I reckon it's bloody worth it

anyway to be living amongst your own sort'.

'Mickey sniggered. 'Not 'alf'.

Len opened up the back of the van, the tail board smashing down to earth

unapologetically. As they say, Len had muscles on his muscles. He pulled out

most of the furniture on his back, mechanically and with calculated strain.

Mickey brought in the lighter load and collaborated with Len on big stuff.

Tadpole carried out the bits and pieces.

'I'll give you a hand with the stereo system pal' said the man 'I know you're a

pro but it did cost nearly a grand you know?'.

'Ricki' chastised the woman 'stop playing with that lad, he's supposed to be

working'.

'Look pal' said the man 'them beds aren't round so you can roll them up the

stairs you know? Hell of trouble getting sheets for them'.

The woman supervised Len and

Mickey's journey from the van with the dishwasher.

'Bloody heavy' said Mickey 'sure you took the plates out?'.

'Hang on lads' exclaimed the man 'I know that you know all the ropes but you

just can't have a tea-break until you've unpacked the kettle can you?'.

'Honestly madam' said Mickey 'It won't matter if I carry your colour telly in

upside down. The newsreader's toupee ain't gonna fall off is it?'.

'Come off it son' said the man to Tadpole 'I know I told you to be careful with

the L.P. record collection but there's no need to be funny about it is there? You

can take them in more than one at a time'.

Ricki rode his own bike into the house and Tadpole took hold of a long think

china vase. A pity really.

'You stupid cripple' shouted the man. Fierce. 'You're a bloody clumsy sod ain't

you. The woman just stood with her hand to her brow in a mock faint position.

Little Ricki looked fearfully from father to Tadpole and then back again and

Mickey let his fag go out.

Tadpole was looking at his feet. They nestled uncomfortably amongst the chunks

of smashed vase on the stone pathway. Despite the happy marriage of family and

home this particular object had refused to be carried over the threshold. The man was moving slowly towards Tadpole from the hallway.

'If you worked for

me I'd clout you, you bloody good for nothing.

Look at you. Can tell from a mile off that you're a bloody liability" A cough

signalled the coming of Len. He was lugging a sofa in from the van single handed

but seemed to have summed the situation up in one.

'Nobody gets moved without having something broken' he spluttered 'it's just not

possible. I'll tell you what, we'll knock a bit off the bill. Don't forget, no

matter how bad things seem they could always be worse'.

True, worse things had happened on past jobs that Tadpole had heard hushed

whispers about, but the Golders Green Grand Piano tragedy was something Len

forbade talk of.

'Still, there's no point you lot standing about staring is there? Get a brush and

pan and sweep that mess up. There's plenty more to shift yet'.

And that was that, anger diffused by Lens breezy yet almost abrasive tones had

turned the whole disaster into a minor couldn't-have-happened-otherwise

incident.

Smiling, Len crouched down beside Tadpole, whispered

'You are a bleedin' silly

sod though aren't you'

The man, the movers, sat around the kitchen table. The woman was making tea and

Ricki was annihilating the forces of Rommel's Africa Corps with an animated

'Action man' in his tiny fist.

Len and the man were nodding in sage like agreement on the wiseness of the

family's move to the new town while Mickey mopped his gradually darkening brow

with a greasy hanky. The woman placed steaming cups of tea in front of the men,

and Tadpole.

'Sorry if things got a bit narky a while back' the man was saying. 'You know how

things are?'.

'Course' Len replied 'Now in my old mans day he would quite often get involved

with hand to hand combat with the clients. We all say things we don't mean

sometimes'. Ricki spoke

'Mum, are all my friends going to move here as well?'.

'Of course not dear' laughed the woman 'You won't see them again'. The boy

looked surprised, then a little tearful.

'It's alright said the woman 'You'll make new friends here in the new town,

friends more like yourself'..

The boy nodded in incomprehension. Len was chortling away with the man. He lifted the cup to his lips, his eyes on

the pot, estimating how many more cups he might drain from it. The man sat with his legs astride a backward chair, eyeing with pride the

unpacked and still unpositioned furniture.

'Well, Mrs Jones' he said to the

woman 'I reckon they're all going to have trouble keeping up with us in this

street. He winked at Tadpole. Tadpole wasn't listening to the man. He was watching Len's face. Tadpole saw him

grimace and thought for one terrible moment that Len was going to spit all the

tea he had in his mouth right out again, all over the table, all over the man

and the woman and the whole seated assembly. He did.

On the journey back home Tadpole was glad that the noise of the engine

restricted conversation to a minimum, restricted it to a maximum shout.

'Bloody Hell'. It was Len. 'Bloody effing muck, what was it? And that snotty

bloody woman wondered why I spat it all out again. You see the way she looked at

me? Her and that bloody ponced up bloke with all the gold bike chain round his

neck. "Oh it's Malaysian root tea' ' she says. "It's posh tea" she says. "Not

bloody tea at all" I told her, not English tea".

'Aint not such thing as English tea' Mickey mumbled. 'It's all -'

'And just who do they think they are anyway' Len carried on 'the bloody royal

family? I haven't seen so much furniture outside the ideal home exhibition'.

'No harm in having nice things though, is there Len?' argued Mickey. 'No harm in

having a nice house in a nice place'.

'Nothing very nice about them though was there? I could hear all the things that

poncy bloke called Tadpole from inside the bloody van. Didn't hear you say

anything to defend him'.

'Well' said Mickey head down 'the customers always right ain't they? And you

didn't say nothing neither'.

'Well I can't argue can I'. I'm responsible for you lot. I have to sit on the

fence'.

'Well, that's not right either is it?' said Mickey 'You can't sit on the fence

all your life can you? And anyway we call Tadpole names ourselves don't we?

Everybody calls Tadpole names. Names don't hurt. Tadpole don't mind. Do you

Tadpole?'

'The word 'Pillock' came from somewhere.

Wasn't Len's voice, certainly wasn't Mickey's.

There was a silence that stretched from Essex to. Essex Road, the way Len was

driving it didn't take very long however.

'What's the bleedin' hurry Len' Mickey asked irritably, eyeing Tadpole with a

new found caution.

Len was studying a torn off piece of card he had lifted off the dashboard, was

studying the poorly written out address. Was on his way.

Roger Mills

(THAP)

THIRD SHUNT

Eleven times I tried to write

another poem for The Peoples Road.

Five hours within myself

trains were moving,

signals changed,

night gathered immense wagons

in a string of stars,

sun shuffled

shunting dawns,

and I could not write.

I had forgotten myself

in the studied books,

lost my own experience

in the history of others,

become the old events,

and I could not write.

There's learning for you.

The road itself had taught

to live is to be

perception first, then memory.

I remember these lives within

from a sense of being

one with the road,

which book is peopled

as this twelfth success

with what I saw when the eyes were mine.

Joe Smythe

(Commonword, Manchester)

Since his first poem was published two years ago in VOICES 18, Joe Smythe has

had much poetry published elsewhere, culminating in a three-month sabbatical

funded by his union, the N.U.R., in order to write a book of poems commemorating

150 years of Britain's railways, THE PEOPLE'S ROAD, from which this poem is

taken. (See p63 for details).

HOLY JIM'S PRAYER

Oh, Lord, this towns a sinful place

Which me and mine must bring to grace

With jailing, flailing every face We don't approve,

The Law is always right to chase And so remove.

I can't think why I'm hated so

When Law and Order as You know

Is all I aim at here below,

In suitable places,

Order is my favourite though,

Lord, how it braces.

And, Lord, You know my evidence

Carries more weight that it does sense,

And sometimes, Lord, conveys pretence

Of Higher Action,

I'm on your side is my defence

And only faction.

With Martin Webster and the Flag

Two thousand of my lads could brag

They kept our Tameside Tories gag

On free opinion,

Our Fuehrer marched as if to bag

The Old Dominion.

There is a rumour in this town

That I don't like our brethren brown

Or black and shades both up and down The spectrum,

It's just my lads rough humours crown

When they collect 'em.

We'll beat the Commie bastards down,

Delete that, Lord, I must not frown

Politically upon the town

Though, Lord, it grieves,

Knowing the danger any clown

With thought achieves.

Theres too much thinking going on

From folk once satisfied with none,

Who knew their Betters ruled as one

In tune with Thee,

Happiest in dominion

Of men like me.

Now, Lord, these pornographic raids

Carried out by my young blades

Are not, as rumoured, sexual aids

For me and mine,

We keep those tons of naughty maids

Apart from thine.

Now Reggie Maudling, Lord, who died,

Before he could be put inside,

Though no-one ever really tried

To nail him,

Preserve him, Lord, some Scotch applied

And you'll not fail him.

And keep that job assured for me,

Chief of Your Constabulary,

Theres folk up There who shouldn't be

Angelic singers,

You need Top-Cop to set

You free From those dead-ringers.

Joe Smythe

(Commonword)

THE FUTURE IS OURS

Our grandson

is a year old.

Last month he

started to walk;

next month he'll

start to talk.

At the end of

the century he'll

be twenty one

unless we

fail to

stop some

fool from

pressing

the button.

Bill Eburn

(London Voices)

VIOLENCE

I think the parents are to blame,

You're Quite right Joe. I think the same.

When we were kids we were so good,

Behaved ourselves like good kids should.

A perfect world it well could be,

If people were like Joe and me.

HOPE SPRINGS ETERNAL

Hope springs eternal

In the human breast,

Said Alexander Pope.

But if your brains

Are in your breast

It's very hard to cope.

Stan Clare

(Netherley Writers, Liverpool)

THE COCK FIGHT

I had just come home from sea. My mother had promised we would have a blowout

meal come Christmas. She had continually nagged my father to kill one of his

chickens, but my father was adamant; it was war-time, eggs were a luxury, and

his birds were laying, so the answer was always "No!" Mother would not be put

off, she was determined that we would have our blowout.

About two weeks before Christmas the big brown cock, which we had to feed

wearing a gauntlet so he would not peck the hand that was feeding him, gave my

small sister a nasty peck on her chubby little thigh, leaving a bruise. This was

just the ammunition my mother wanted. When father came home he was greeted by

mother carrying my little sister and lifting her dress to show where the cock

had pecked her. Father was very angry and rushed out the back to where the

cock's pen was. He opened the cage door and grabbed the cock by the neck with

the intention of screwing it. Mother and I went through the kitchen to the

scullery window where the most amazing sight greeted us. There was father

rolling on the ground, the cock was pecking him everywhere. Mother screamed with

laughter, and then sent me out to get the cock off my father. When I eventually

shooed the cock back into his cage, my father got to his feet. He was swearing

and shouting about ungrateful birds, though he never once mentioned that he was

trying to kill it. Father went inside and sat exhausted in his armchair near the

fire. Mother asked him, "What about a chicken for Christmas?" He replied that if

she could kill the brown cock, that was the bird she could have.

For the next fortnight my mother fed and fed the brown cock to fatten him up.

Every scrap left from the mealtimes went to him. By the time Christmas week came

along that brown cock had put on another two pounds in weight. My mother was

forever trying to devise ways of killing it, but nothing she could think of

would work. Father had washed his hands over the cock, and concentrated on his

hens. My mother was getting quite desperate - time was running out. Christmas

day was only a few days away. Somebody suggested putting a rope around the

cock's neck and hanging it. Then another suggestion was to tie its legs and hang

it on the back door, putting a block of wood under its neck and chopping its

head off. Mother rejected all of these suggestions and reverted back to nagging

my father to kill it. Until one day he relented, and said he would kill it two

days before Christmas.

Everything was peaceful once again in the house. Mother seemed quite happy, she

was getting what she wanted, a nice plump bird for the blowout. However, my

younger brother who was always getting up to some mischief or other, had made

two huge posters advertising a wrestling match between my father and the brown

cock. He billed it as a fight to the death. When father came home and saw them,

he refused point blank to have anything more to do with the brown cock. Instead,

he killed two of his laying birds. Christmas morning came around; the night

before there had been a lot of celebrating, and father had got rather drunk. The

first thing he heard through his hangover when he awoke was a loud crowing from

the brown cock.

Alf Ironmonger

(Commonword,

Manchester)

I SAW A SAD MAN IN A FIELD

I saw a sad man in a field

Working,

Each day I ran alongside

Waving.

My father said the man was bad

Wicked,

Forbade me ever more to wave

Friendly.

I walked to school beside the field

Crying,

My friend he understood I felt

Sadly.

He was a German, prisoner

Homesick,

He had a little girl like me

Grieving.

Afraid I walked up to the fence

Gazing,

He smiled and shook his head at me

Smiling.

He was young and blond and nice

Enemy,

I loved him very much indeed

Hurting, hurting.

Joan Batchelor (Commonword)

HYMNS ON MONDAY

A summer like honey ...

Yet scented of coal dust,

Treacle hot and languid,

Lazy on my back ...

As I shared washday,

Like a picnic, outdoors.

A tin bath of suds

On a wooden chair

And a bucket of cold water

To rinse away the soap.

Our children with fingers

Trailing suds and laughter.

Snow-white washing

Finding a slight breeze,

A sensual dancing,

Bleaching in the sun.

Comparing my washing

With the woman's next door,

As we sang, hymns on Monday.

Then pouring away suds

And chasing away small feet

Which wished to stamp bubbles.

Then we sat, on baked steps,

To prepare vast, family pots

Full of home grown vegetables,

Handing out cabbage stalks and carrots

To grubby, eager little hands.

Laughing, chiding, singing,

Fingers nimble,

Sharing family recipes,

Village gossip,

Companionable.

Teaching our willing children

Hymns on Monday.

BUY ONE? I WOULDN'T TAKE ONE AS A GIFT!

He stood there, bluffing away his horror.

The ultimate had occurred ...

My daughter, with guileful innocence,

Had invited this local candidate in.

He looked miserably out of place,

Like a diamond in a coal-mine,

His smile hanging on grimly,

His plum-stone stuck in his throat.

So this is what, for many years,

They had promised to improve...

Sideways noting this corporation dump,

The task seemed to overwhelm him.

He dropped bright election posters

Onto the uneven floorboards..

As the cat lovingly caressed

White fur onto his well-cut suit.

He swallowed his uncertainty,

And, with difficulty, forced a beam

Nearly cutting his perspiring face in half.

"Could I count upon your support, madam?"

... I looked at him, so ill-fitting

In this place I called my home,

Uneasy before my cynical demeanour,

I felt superior. . . could he buggery!

Joan Batchelor

FALSE REWARD

Sure dey told me

dat ah wuz no longer

Prince Of Freedom,

but dey nayfur sed dat der

chains of justice

would swing ma arms

and saliva

would bury ma lips.

& into der dead sunset

ah walk like

carryin yaw gift of

gratitude

false reward

around ma neck.

Man, ah ahm one of

der grey people

& ma cloudeyes

looks like luminous dials

as ah cry outward

thru yaw dark passage

ware small children

sing in sorrow

frum lair dead mouths

& wheels of war

crunches lair bones

into yaw grinnin hands,

& proud smile.

Blackie Fortuna

(Oxford)

THE BUFFER'S TALE

A TALE TOLD DURING A FIVE-MINUTE LULL IN THE

BUILDING OF A FRIGATE

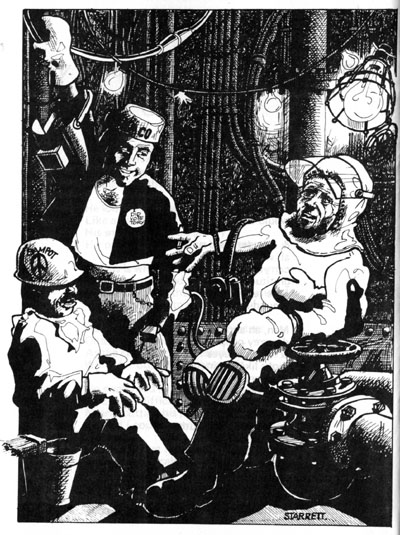

The metal buffer took off his mask, wiped his sweat-streaked face with his

sleeve, put down his screeching buff and lit a cigarette. He looked round in the semi-dark of the engine room and nodded to the two others

who shared this part of the ship with him. They were glad the buffing machine's

dreadful noise had stopped, if only for a few minutes, even if it left behind

the ghost echo, like the sound in a seashell. They nodded back and quickly got

into conversation without any of the preliminaries that most other social groups

effect. The reason was simple enough. Any moments of relative quiet had to be

taken advantage of, as in a shipyard such moments are few and far between.

"Jesus, it's hot doon here," said the buffer as an opener. One of the others, a

welder, said from out of the semi-darkness, "Naw it's no'. Ye should feel the

heat o'er in that Spain - that's whit ye ca' heat."

"Spain, did ye say?" said the buffer. "Is Burma any good tae ye? An whit aboot

India, eh?

"Where ye there then?" the welder inquired.

"Aye I was, many years ago. I was wae the Chindits y'know. Wingate an' a' that.

I can see it the noo as I'm talking tae you. Ye've no seen nothing till ye've

seen that daft jungle. It's the darkest green and aye wet. You think we've goat

rain here? You should see the monsoons! An' see oot there, the stars are bright

as anything - like a lot o' new shillings in the sky. No' as bright as the stars

frae the troop carrier, mind you, but maybe they only seemed brighter because

yer happier on the deck o' a boat instead o' building wan.

"Hiv yous no' seen the Iddywaddy river at a'?" he queried. "No' even at school?

Christ, the forgotten army right enough! We waded across it wance chasing the

Japs... wait a minute.. . I'm a wee liar. The Japs were chasing us. But no

matter, that river is magic - aboot three times as wide as this wan," (he nodded

at the hull in the direction of the Clyde), "an' full o' queer looking fish tae.

See in that jungle, there are millions o' birds o' every colour in the rainbow.

An' see you painter," he pointed at the painter, "You'd go off yer heid tryin'

tae mix up a shade anything like them. Same wi' the flooers, but they're a'

poisonous, so they're bad news."

He sighed and looked at his near-finished cigarette. "Some days I can see it so

clear in a' its technicolour that I'm there y'know."

The painter, having been brought into the conversation, turned to the buffer and

smilingly said, "If you won the pools and you had the dough tae go anywhere in

the world, where would you go?"

The welder and him exchanged winks as they waited on the reply.

"Anywhere in the world, ye said?" questioned the buffer, as he slowly took a

last draw on his cigarette.

"Aye," chorused the other two.

"I'd be away doon tae London like a shot. It's fuckin magic!!!"

And with that, he replaced his mask and the dreadful noise commenced again.

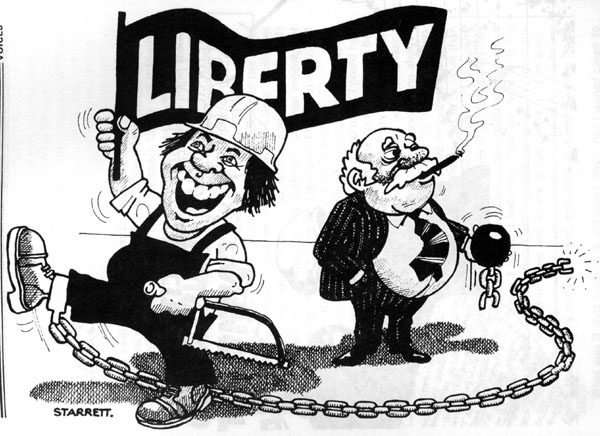

Bob Starrett

(Glasgow)

NIGHT SHIFT

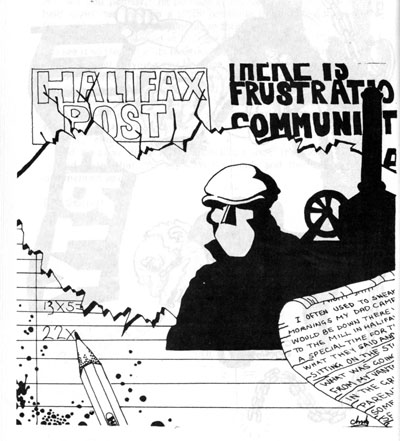

I often used to sneak down the stairs early on the mornings my dad came back

from the night shift at the pit. Mum would be down there with him, getting ready

to catch the coach to the mill in Halifax where she worked. I knew that this was

a special time for them, so I felt excluded. I wanted to know what they did in

their special moments. Sitting on the stairs halfway down I could hear what was going on in the kitchen

and still make a quick escape if either of them came towards the door.

From my vantage point I could hear the fire crackling in the grate, the sounds

and smells of breakfast and my parents' voices, sometimes soft and low,

sometimes laughing, sometimes harsh and angry. It always amazed me how they

seemed different, like real people, not just parents, when I wasn't there. As I

got older I began to wonder if having me hadn't stifled them, stopped them

growing.

One particular morning in the middle of winter, in the late 50's, I had crept

down and been shocked at the anger and upset I could hear coming through the

door. I wanted to rush back up to my warm bed and feel safe, I felt that this

was one time I really shouldn't have been listening. But I stayed, drawn by

curiosity and not a little fear.

My dad was talking about a strike at the pit, something about a deputy

victimising him. (I made a mental note to look up "victimising" in the

dictionary at school,) Mum seemed very upset and angry and was arguing about the

dispute, but there seemed to be more than this, I'd obviously missed the vital

part. I felt confused, I knew mum had always supported dad before, even when the

local papers had said he was in the pay of Russia. (That caused quite a stink at

the Catholic school, where I went, I had more than one fight with the other kids

and some teachers.) She had taken snap and tea up to the pickets with the other

wives and let me go on picket duty at weekends. I'd found it all really

exciting, newspapers and radio people and even some M.P.s milling around, and

most of them interested in my dad!!

What was it that made it so different this time? I leaned closer to the door to

catch what Mum was saying. When she was really angry her voice became very low

and her Irish accent got stronger.

"I'm buggered if I will, how will we eat, it was bad last time and no official

backing. Jim, you must be mad!"

"You will Josie, because you have to. The papers would have a field day and we

must keep solid."

What didn't she want to do, it sounded awful, what was dad on about? In my

excitement I fell against the banister and made a loud bump. Quickly, I crept

back upstairs and jumped into my now cold bed, closing my eyes tight to feign

sleep. Was someone coming upstairs? I lay perfectly still as my bedroom door opened, and then closed again quietly.

My heart was thundering as I lay there straining to hear what was going on. I

stayed in that position for about an hour until I heard my dad shout up that it

was time to be getting out of bed.

Mum would always be gone to work when Dad shouted me, then it was my special

time with him. I loved those mornings especially in winter. He'd have breakfast

ready and we'd sit and talk in front of the fire, drinking strong tea. I'd tell

him all about the indoctrination - as he called it - at school and he'd put up

arguments against the things I'd been told. I used to get into terrible trouble

with the nuns over some of the things I said in class and wrote in my essays.

However, on this morning I felt a bit nervous as I went downstairs, legitimately

this time. I opened the kitchen door. Everything was aglow with firelight and

Dad was there, sitting and staring into the fire. He stood up as I came in and

gathered me up in his arms, hugging me.

"Hallo my lovely, you must have been cold sitting and listening in, come on, sit

by the fire."

I felt a sickly thud in my stomach, so he knew. But he was smiling and passing

me a cup of tea. I could see how strained he felt as I looked closely. Apparently the strike at

the pit was in support of him, the pit management were trying to get him out

again. He'd told Mum that during the strike she must give up work - so that was

it - and she's gone in today to pick up her wages and get her cards.

"Why does

she have to, Dad?" I asked. I really wanted to know.

Dad explained that if Mum went on earning during the strike it would weaken

their case. People (papers, management etc.) would say that Jim Connelly was

O.K., his missus was earning to keep him out on strike. He said it would be

wrong, that all families had to suffer the same. It seemed so obviously right when he explained it. I couldn't understand why Mum

had been so upset. However, over the 2 months of the strike I realised the

struggle to stay with it was taking its toll of everyone, especially the wives,

who did the 'managing' as usual.

Eventually the miners won their case, Dad was reinstated and I expected

everything to return to normal. But it didn't. Mum never went back to work at

the mill. She said if we could manage without any wages during the strike we

could manage with one pay packet now. Dad grinned and sold his scooter, which

had been idle throughout the last 2 months anyway. I lost my special morning

sessions with Dad, because Mum was there now. At first I felt resentful but then

I found that she had opinions to voice about my school work too, and we used to

have some fine old discussions over breakfast.

I never crept down to listen at the door again. Dad had known I was there all

the time and anyway I knew now that with me, or without me, they were real

people.

Kitty Williams

(Bedford)

I DON'T BUY SOUTH AFRICAN

Are they South African

She asked

Her voice nervous

And hesitant

As the oranges tumbled into her bag.

Why do you ask?

I don't buy South African

She said.

Why didn't you say so before.

What's wrong with them?

He snapped,

Taking the fruit back,

And I saw in her tormented eyes

Black people picking oranges

Slave labour

On

Afrikaner farms

Black children suffering hunger,

Families torn asunder,

And as her eyes blinked nervously

A man fell

From a sixth floor window marked Police.

She coughed apologetically,

I don't buy South African,

And she left.

Bert Ward

(London Voices)

THE HATPIN

An hour after the children had left in a tangle of satchels and

Wellingtons, she

was still sitting at the breakfast table, elbows placed carefully between the

wreckage of the meal, not thinking about anything in particular. She watched the

spiral of her cigarette smoke, contemplated the yawning sink and made temporary

plans concerning cupboards and sheets. She lit another cigarette and watched it

build up a fragile cylinder of ash, calculating that it would fall before she

had gathered the spoons together. It did. The dishes were left to drip dry. She

had started the practice after reading a magazine article that condemned the

germ laden dishcloth. Her domestic pride had accepted the scientific reasoning,

she no longer felt guilty about it. The beds clamoured to be made. She pulled

them together from one side, smoothing out the bumps with her hand once the

counterpane was on. She considered polishing the wood work but decided it didn't

look too bad. The mirrors had used up the day before. The thought of tidying the

children's room appalled her and she settled for cleaning the stairs as a poor

but better alternative.

She stood at the top of the stairs looking down. Seven, landing, seven, landing,

ten, she thought, plus the one I'm on. She bent over the bucket with his head of

foam and plunged her rubber hand into it, pulling out the saturated rag that had

once been the arm of a shirt. The foam knee-pad cushioned her knees and she

began to push the rag across the wooden boards. The hot water melted the inner

surface of the stains with the first stroke. She had to press her knuckles into

the rag to erase the outer rings. She tried not to recall the history of the

marks, but she knew each stain, just as surely as she had counted them up until

they were undeniable and she had to destroy them.

Her sandal somersaulted down the stairs as she came to the set of stains on the

top step. Robert's coffee. He always managed to keep the cup level until the

last flight, but there were always tooth-edged circles on the top steps. She

forgot the sandal and washed the stains away. Two steps down she had to work

with a knife at some unidentifiable lump of sticky matter. Chewing gum or model

glue, she guessed, and levered the hard knob away. She reached the bottom of the

first flight without further incident.

She worked faster on the landings, scraping at the cracks between the boards

with a knitting needle, flipping out small objects that had worked their way

into the narrow slits. Then she stretched with both hands on the rag and drew it

towards herself in a single sweep. She hummed a sea shanty to herself,

pretending she was a deckhand on a galleon as she exaggerated her movements

enough to feel them in her thighs. She made herself go back to the edge when she

saw she had missed an inch-wide strip, and remembered to go over the patches her

shoes made in the wet gloss she had to step over. She looked forward to the next

flight where she knew her hatpin lay and anticipated its removal while she

swished across the last strip of landing. She stopped humming and thought up a

game to play. If I don't find the hatpin, she thought, Robert will leave me. She

considered the exchange, wondering if it wasn't a little too generous to offer

Robert against the near certainty of the hatpin being where she remembered it.

It's no fun if you play safe, she decided, and accepted the conditions she had

suggested. She would change the water at the bottom of the flight too. It was

getting cold and she couldn't bear cold water.

The steps smelt damp above her, she reached the place where the hatpin lay and

ferreted around with the needle. It must have been jammed because she only

disturbed a rusty paper clip. She tried again, peering into the slim opening but

she couldn't see the blue tip, and again only received a midget dust storm when

she jerked at the needle. It must be the next step, she thought, and wiped the

step clean.

The needle slipped along the gap. She pressed it into the opening until she felt

the resistance of the wood behind it and catapulted a mist of grit and dust all

over herself. There was no hatpin in the powdery mound. She rose from her knees

and counted the steps, thinking back to the exact moment when she had first

noted the tip, but she was sure she had the right place. She hadn't picked it

up, she had planned to extract it when she washed the stairs, she remembered

planning it. Oh, this is ridiculous, of course, one of the children must have

seen it. She shook herself and began to wash again, but to be sure she left her

cleaning at the last step and opened the door of the children's room.

The jam jar they kept their oddments in was brimming with buttons and blunt

pencils, and she tipped them all out on the dresser to see better. A blanket

glance over the visible surfaces of the room revealed nothing other than the

fact that the elder child had not made his bed. She flipped back the clothes on

the table and looked under the beds, having to stop and picture the hatpin

because, for a moment, she had forgotten what she was looking for. She left the

room annoyed. There was no hatpin there unless one of them had hidden it. The

game impinged on her mind and she threw off the reminder with a frown. Bugger

the silly thing, she thought.

Reminding herself to deliver the children's supper herself in future, she swiped

at the orange juice spillage on the stairs. No need for all this mess, they

wouldn't use a tray. She prodded after the hatpin on the landing. It might have

fallen again, she reasoned, and told herself that she wanted to locate the

hatpin because it was possibly dangerous to leave its three inch pin exposed on

the stairs. Her stomach twinged at her and the biro that obstructed her progress

on the next prodding operation made her laugh in anticipated success, until it

revealed itself. She skewered her knuckles into a crisp food stain and pushed

until she was hurting herself. The edges of the stain surrendered and dissolved

into the steamy rag. She sniffed at it and pulled a face. Embarrassed by her own

behaviour, she threw the rag into the scum-covered water and shook the fibre

worms from her gloves with a shudder. She needed a drink. She went to the

kitchen but couldn't be bothered to boil up the kettle, she never enjoyed tea on

her own and she had run out of filters for the coffee. She inspected the larder

shelves and found an unopened jar of dried lemon tea, but pushed it to the back

of the larder without opening it. She took a glass and a bottle of the

children's lemonade and poured out a full glass, which she drained in one

swallow. "Revolting", she said to herself after the coughing was over. She

climbed the stairs again.

The water in the bucket had gone cold and slimy with congealed soap powder but

she didn't change it. The trudge back down the stairs seemed a needless bother

when there was only the last flight to do. She began to hiccup and tasted the

nauseous lemonade with each jerk. The game came back to her and she checked her

chances against her memory. She was certain it was there somewhere, no real

danger in the bargain she had made, and she felt a surge of excitement stir in

her stomach as she deliberately increased her risk by moving to the next step. Recklessly, she wiped it clean with three quick strokes and suffered an instant

regret at courting disaster so thoughtlessly. She made up the frittered time by

wiping the rim of each step in slow motion and when she calculated she had made

up the lost time, she took up the needle again and began to search. The dust was

a uniform grey. She laughed nervously. Eight steps left.

She began to work with exaggerated caution, doing the prodding twice at each

step, investigating the small impedances that drawing pins and match sticks made

to her progress. Concentration on the digging made the wiping superfluous and

she ignored a solid toffee ring, greedy for the time it would have taken to chip

it away. The needle stuck in the fourth step and she dragged hopefully at a

rigid obstruction, sure of success, and felt a pitching disappointment when she

dislodged a pearl button, even though the blouse it belonged to had lain unworn

since its loss. She threw it down the stairs and did not look where it landed.

Not enjoying the tension of the game any longer, she began to retract on the

conditions of the game. She changed Robert leaving to Robert being late home,

but the original agreement clung to her mind and the thrills in her stomach came

fast and sharp.

The thought occurred to her that she could leave the rest of the stairs

unwashed, so winning the game on a technicality. She would have to remember to

leave a portion unwashed the next time she cleaned them. As long as she did

that, she could keep the game in limbo until the hatpin turned up. The stomach

surges and her entirely practical scruples about cheating drove her on. She

would devalue the game forever if she did. She pushed the rag along with one

finger, lingering over a milk gear wheel as she thought. Perhaps Robert had

lifted it. How bright was the tip? Bright enough for him to notice? She thought

not, but how was she to know, she asked herself in perplexity. The damp from the

step soaked through her skirt and made her jump as she felt it seeping into her

thighs.

Oh, what am I doing? Playing children's games, she thought. What a fool. God,

look at the time, I should have started the dinner, it'll never be ready. She

looked at her watch. She felt lighter, freed from the turmoil in her stomach and

caught up in her own relief, she swiped at the last three steps with a strong

hand. She flicked the needle along the cracks and laughed aloud when the dust

emerged colourless. She tossed the dirty rag into the bucket and watched as it

sank slowly into the semi-solid contents. "Ugh", she said. She looked up the

stair well.

The telephone rang. It was not a loud bell, but the shrill sound fracturing the

silence petrified her where she stood. The stairs were clean. The hatpin had not

been found. Robert had left her. Its logic stunned her. Her levity collapsed and

she stood at the bottom of the stairs and listened to the bell as it continued

to shred her calm with each jangling rip of sound. The stairs faced her, the

stairs she had cleaned after making the bargain. Every step, every surface

gleamed damply. Robert had gone.

The bell stopped and she moved. She ran to the top of the stairs and fell on her

knees, lacerating her nails as she tore into the cracks on the top step, numbed

with fear and premonition. She was whimpering when she saw it, obvious as the

sun, very near the surface of a crack in the third stair. She fumbled for it and

held it so tightly in her hand that the tip punctured her palm. She hovered on

the edge of the step, searching the rules for an escape. Did it count? It had

been there. She had missed it but it had been there.

The telephone rang again. She leapt the stairs in twos and threes, crashing her

shins against the corners, and wrenched the receiver from its cradle. "Y-es! Y-es!"

she shouted into its plastic mouth. The empty crackling frightened her.

"It's all right, darling. It's only me. I 'phoned earlier but you must have been

in the garden. Just ringing to say I'll be home early tonight. About five. Are

you all right? You just about blasted my ear off just now, he laughed and she

answered him, yes, she was fine, busy cleaning, and she put the receiver down

shaking. She turned to the stairs.

"You see!" she said, "You see!"

Vivien Leslie

(Castle Douglas, Scotland)

Readers' Roundup - RICK GWILT

TO STRUGGLE IS TO LIVE. Volume II. "Starve or Rebel 1927-1971". Ernie Benson.

280 pages. £1.90. People's Publication.

REVOLT AGAINST AN 'AGE OF PLENTY'. Jack Common. 140 pages. £1.30. Strong Words.

In some ways these two books may be seen to complement each other. The second

volume of Ernie Benson's autobiography concentrates on the economic and

political dimensions - the means test and the National Unemployed Workers'

Movement, trade union struggles at the workplace and out in the streets. A

fascinating story, which the author re-lives with such zest that you will

probably be unable to put the book down.

Jack Common, on the other hand, in this posthumous collection of essays written

in the 1930's, concentrates mainly on the cultural dimension (in the broad sense

of attitudes and customs rather than the literary sense). This, I feel, is both

a strength and a weakness. He is undoubtedly right to say that socialist

intellectuals have paid too little attention to the cultural question. He

accuses the Fabians of "the old mercantile notion that culture is a commodity

which can be transferred from one kind of man to another, not a grace belonging

to a kind of life; and the worse conviction that if you do up a chap in your own

duds you've done him proud. These beliefs have sprinkled Africa with gramophones

and top-hats." Also coming in for some stick are the surrealists ("They put

their shirt on nightmare as a dark horse, but they take care to hang on to the

cufflinks") and labour leaders ("Socialism survives its leaders as Christianity

survived the popes. It lives on in the body of the kirk"). Common is at his best

when his pen is biting into the very paper like this, but in between you get the

feeling of a man who is politically confused taking wild swipes in all

directions.

The editors deny that Common is ever guilty of "workerism", but I

gradually realised how come a working-class Geordie lad like him got to be such

big mates with a bloke like George Orwell. The dividing-line between what is

radical and what is downright reactionary in his ideas is often dangerously

narrow (I sometimes had the feeling I might be reading Keith Waterhouse in the

Mirror), and ultimately, what Common says about the way socialists slag

capitalism seems to apply equally well to the way Common slags socialists: "Too

often the result is to produce cynicism. When men are shown universal injustice

they lose their old faith but do not necessarily get a new one."

Which brings me to the weakness of Common's approach - his view of working class

culture is basically nostalgic and backward-looking, as with many writers who

are from the working class but no longer in it. In a decade when Ernie Benson

and millions of others are experiencing poverty and unemployment at first-hand,

Common seems more affected by the growth of consumerism and the erosion of the

old traditions. Common writes immortal lines like, "The pay-packet is a sort of