|

ISSUE 22

cover size 210 x 148 mm (A5)

EDITORIAL

VOICES 22 marks our first issue since we were formally "adopted" by the

Federation of Worker Writers and Community Publishers at its AGM at Nottingham

in April. VOICES, from its fairly orthodox labour movement origins, and the

various worker-writer groups, from (their backgrounds of community politics in

one form or another, have long been on converging paths. Since fairly early

days, VOICES has been national in scope without ever evolving a structure to

match its content. The Federation of Worker Writers represents possibly the

biggest single new contribution to working-class culture in recent years -

certainly in the field of literature - and yet, despite a wealth of occasional

and local publications, it has never had a regular national mouthpiece. The two

organisations already share a common perspective; now VOICES has a ready-made

management group and the Federation has a ready-made publishing group, which

will continue to be based in Manchester.

So before any regular readers go scurrying for their back numbers in an attempt

to spot the difference, I should emphasise that continuity will be the keynote.

We have been given a clear go-ahead to carry on with our own mixture of

dependability and unpredictability without becoming anyone's "tame mouthpiece".

We are publishing the Federation's letter to the Arts Council not least because

we consider it important from the point of view of both working-class culture

and public policy towards the Arts generally. But we continue to give space to

material sent in by isolated individuals as well as members of worker-writer

groups. If we can overcome the organisational and financial difficulties, we aim

to establish a nationally representative editorial board eventually, but at the

moment it is as much as we can manage not to sink completely beneath the

existing workload, while attempting to return to regular quarterly publication,

I do not see "continuity" as meaning that we stand still. Over the last few

years we have been changing steadily, moving away from propagandist writing and

towards writing in which people draw more directly on their own experience.

Blake Morrison, in his unpublished report to the Arts Council, has noted this

with approval: ". - . The weakness of the magazine has been to print bad poems

and articles simply because they express "good", be. politically acceptable,

opinions: shallow and overt propagandising has been more common than work of

literary merit. - - - I noticed a definite improvement both in the contributions

to, and the production of VOICES between the first issue of 1975 and the recent

VOICES 20..."

On the other hand, I know there is a feeling amongst one or two of our

longstanding supporters in the labour movement that VOICES has "gone soft". I

feel that people who are adding the weight of supporting VOICES to other trade

union and political commitments to be faced after a hard day's grind are more

entitled to their criticisms than most: a satisfying, well-paid lob as an

armchair critic would doubtless make most of us more tolerant - and more

tolerable. And of course, under a Government that is already hitting most of us

with financial hardship, not to mention the threat of extinction, the call to

"art for art's sake" is bound to sound even hollower than usual. But I also feel

that such criticisms are misplaced. Banging the drum as loudly as possible is

not always the best way to get people dancing, even if the Dave Clark Five did

get away with it for a while. Bert Brecht once announced to the bourgeois

theatre that its entertainment was no longer instructive and the time had come

to see if there was anything entertaining in his kind of instruction. I think

the time has come for worker-writers to say to much of the Left, and certainly

the left press: "There is no longer anything entertaining in your kind of

instruction. Let's see if there is anything instructive in our entertainment."

The question of "obscenity" and "bad language" remains a more difficult problem

for the editors to deal with. To some extent I feel that the offence is in the

eye of the beholder, but as a magazine that actively encourages readers'

criticisms we can hardly turn round and ignore the views of the "beholder" - and

we don't, Personally, I use swear words sparingly in my own writing and advise

other contributors to do the same. But I do not regard people's natural

functions or their sexual activity as unspeakable or unprintable, and I would

not like to see contributors discouraged from venturing into more personal

matters rather than sticking to "safe" political themes. Too many of our heroes

of working-class literature make only brief reference to the wife who

mysteriously fails to understand their political commitment.

When I was a lad, I remember the TV newsreader announcing, with a suitable

expression of disgust drawn across his face, that the sick comedian, Lenny

Bruce, had been refused entry to the country. At the time, I was too young to

know what sick humour was, and my parents were too old to tell me. Nowadays

there are things I do regard as very sick, but Lenny Bruce isn't one of them.

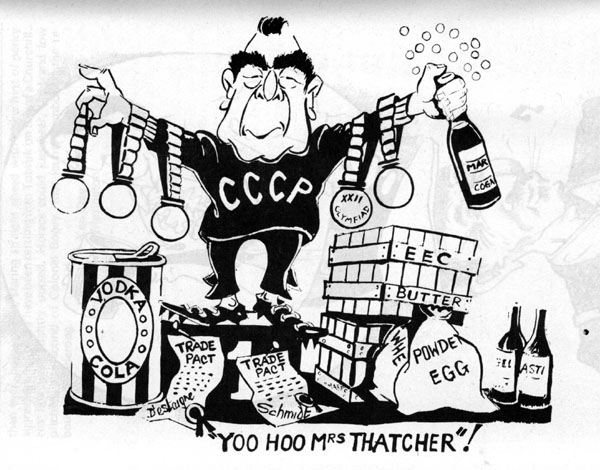

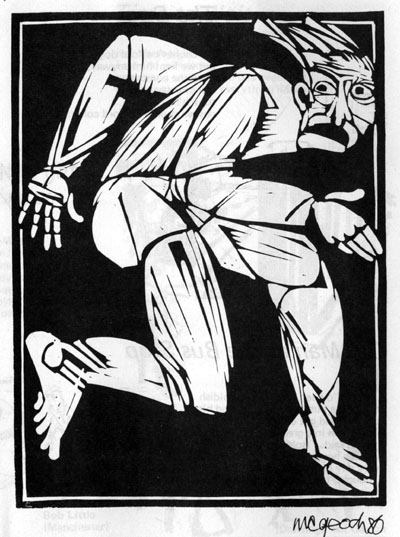

There is a more general problem for the editors which arises out of certain

types of criticism. For example, the cover illustration for VOICES 21 aroused

strong feelings both for and against: people either loved it or hated it. Do we

censor such a cartoon in deference to those who may be offended, thereby

depriving many readers of a great deal of pleasure? Do we print only those items

which we feel sure will offend nobody? The problem is much wider than one

cartoon: most of the cartoons in VOICES 21 have met with strong criticism from

some quarters, as have many of the best stories we have printed over the years.

When we get letters of criticism, our policy is to print them, space permitting.

Perhaps because we are an unusual sort of magazine, most criticisms tend to

reach us by word of mouth, in which case we try to pass the criticism on to the

writer or artist concerned, who must then decide whether to reject the criticism

or to accept it and take account of it in future work. Over all I feel VOICES

must continue to risk controversy and hope that our supporters will stick with

us even though they don't approve of everything we print. The alternative would

be to be as bland as the proverbial frankfurter sausage, and I don't think any

of us would want that.

Sometimes it seems that the pressures on a magazine like ours grow greater the

longer you keep going, which is perhaps why a literary magazine running to 22

issues is such an uncommon achievement. An irate contributor once described us

as "a bunch of f---ing amateurs". I think this was intended to be

uncomplimentary, but it is also quite factual. We are all running VOICES on top

of our work and family commitments, so we hope that all those waiting patiently

for a letter, return of material, or simply the next "quarterly" issue, will

bear with us as we soldier on, determined that whatever else happens VOICES is

not going to fold under the pressure like so many magazines before us.

Rick Gwilt

COME BACK JACKIE BROWN

Once you could ring a bell on Oldham Road

and boxers would come sparring from every pub,

dodging drays with broke -nose adroitness,

right-crossing traffic lights, uppercutting constables,

feinting a right-hook for a straight-left,

gay as cauliflowers, familiar as mastodons.

It was a long time ago. Today I saw

an advertisement for professional boxers,

as if that breed had merely moved away

not vanished with the years they flourished in,

hungry as danger years, raged-at years,

it was a long time ago. Today I saw

an advertisement for the good old days,

crafty men with knowing wallets placed it.

Joe Smythe

(Commonword, Manchester)

CARTOON FOR THE

LABOUR MOVEMENT

We said to you - you wouldn't heed –

we said to you: 'Be careful'.

You said: 'There isn't any need,

They're learning to be gentle'.

We said: 'They're of the tiger breed

and waiting for their chance'.

And here they are in word and deed

preparing for a pounce.

You can't put tigers on a lead

and train them to the house.

Frances Moore

(Sheffield)

DANGER MEN AT WORK

If Albert Broome had worn a beret and khaki shorts and been seen occasionally

with his head sticking out of a tank he'd have been indistinguishable from field

marshal Montgomery, And, to complete the comparison, if the field marshal had

worn an oily, brown boilersuit and flat cap and worked the drilling machine in

the Inorganic Section fitting shop he'd have been a dead ringer for Albert

Broome. Like the great general Albert had sharp, ratty features, fans of fine

wrinkles at the corners of his eyes and a back so straight it was almost a

military caricature. The other quality he shared with the hero of El Alamein was

the same expertise in the practice of drilling.

For forty years Albert has been attached to engineering like a half-sucked

humbug is attached to the inside of a kid's pocket - loosely, neglectedly and

collecting a mass of woolly debris from his immediate environment. Concerning

the simple craft of drilling itself he'd learned next to nothing. He could

cheerfully watch a series of sixteenth drills churn laboriously through a brass

bearing at two hundred revs a minute before breaking in half, or, with equal

insouciance, attempt to push a monster inch and a quarter through stainless

steel at ten times that speed and marvel at the noise and smoke. Harry Furneval

had been told to keep an eye on him and change his gears when necessary. The

grindstone had been off-limits since he'd reduced half a dozen high-speed

Dormers to what looked like king-sized toothpicks.

Broomie's real genius was for scavenging and today had already made a very

promising start. As soon as he got to his machine he noticed a pound note

sticking out from under his rubber mat. A big shot of adrenalin jerked him out

of his early morning torpor. If he could just keep at least one of his size

nines over it till the other greedy bastards left the shop he could clean up

quietly and avoid a riot. After a lot of surreptitious shuffling he managed to

cover it with a six inch flange. And, if that wasn't luck enough, Barrow had

brought a jacket in from the shop benefactor Arthur Broadfield. Arthur was on

holiday but Barrow had seen him in the pub the night before and the precious

brown paper parcel was in the back of Barrow's car right now. He'd be sneaking

it in later; sneaking, that is, because of Horace Walmsley who was in

competition with Broomie for these handouts. Strictly speaking it was Horace's

turn and Albert had been warned to keep it hidden till he got home. His daydream

of riches was suddenly disturbed by a muffled rumble from the amenities area. An

agonised bellow followed: young Ronnie Cornes had opened his locker and nearly

got knocked over by a bouncing deluge of old rubber boots.

"The phantom strikes again!" somebody shouted. For Ronnie it was a re-run of one

of the great mysteries of the universe. It had happened first three months ago

just after he'd joined the shop. He'd unlocked his locker one morning and found

an enormous pile of junk - screwed elbows, joint rings, stud couplings, valve

bodies, gland packing, pump impellors all stuffed into that vertical,

coffin-shaped container which normally housed only his personal effects.

Somebody obviously had a key. He bought another padlock, a real Castle

Frankenstein job with a hasp on it half an inch round. Incredibly it happened

again! And this time the dirty swine had included a dead hedgehog! Ronnie was

furious: he saw Blinston the foreman. Nothing was missing though and Blinston

just issued a vague, general caution. Then Ron fitted the Ultimate Protection. A

month passed, the device remained unbreached, Ronnie began to feel secure. . .

until today! Again!! But how? A small crowd was already winding Ron up to new

heights of rage.

"How's he getting in Ronnie?"

"He must be a bleeding genius!"

"I reckon he's got a master skeleton key." The notion was taken up.

"Of course! A master skeleton key!"

"Bloody skeleton key?" shouted Ron on the edge of a tearful hysteria, "How could

he?" Ronnie opened his hand to reveal, to those who pretended they hadn't seen

it before, the Unbeatable, the Impenetrable, the Unpickable.

"It's a bloody combination lock!" There was a brief silence while they gave an

excellent imitation of hard thinking.

"He must have hit on just the right combination Ron" said Barrow pursuing the

problem with remorseless logic.

"With five soddin digits?!" Ronnie was doing HNC at night-school. He rarely lost

an opportunity to display his superior learning. The lads realised he wouldn't

be with them very long and did their best to make his stay as interesting as

possible. And, to be fair, serious, studious, young Ron always did his best to

enlighten their ignorance. Hadn't he spent all one afternoon trying to explain

to old Barney that screw cutting a left hand thread in Australia was no

different from doing it here?

"That means one hundred thousand combinations" Ronnie went on, "Who could

possibly try all those positions?"

"I've only managed forty eight myself" said Ernie Hardman.

"Have you tried lying on top of her?" said Owen.

"Christ no! Forty nine!"

"If you set one up every fifteen seconds" said Ronnie ignoring this diversion,

"it'd take four hundred and sixteen hours to try them all." Ron knew these

things; he'd worked it all out just after he'd bought the lock.

"That's over seventeen days. twenty four hours a day!" Another stunned silence

was followed by the final, killing comment on this statistical analysis.

"Well how's he getting in then?"

Ron clenched his teeth and started to chuck out the remaining boots. "I'm blowed

if I know" he said, pressing the steel sides yet again in search of a sprung

seam. "But I'll find out if it kills me!"

As they drifted off to work Barrow took an acrobatic dive over Broomie's flange.

"Aaaaaagh! Jeezus Albert, that's a flamin hazard that is! Nearly had a lost time

accident there!" He made a move to pick it up but Broomie was out of the

cupboard so fast he banged his head on the doorframe. "Its all right Alan. Leave

it there will you."

"Dodgy Albert, we cant have flanges lying about everywhere, Blinston will do his

nut. Here, I'll give you a lift with it on to the bench." Broomie hastily trod

on it.

"No, you get going Alan; I'll see to it. You'll be down on bonus messing about

here."

Barrow moved away but before he got to the door Albert remembered something.

"Ey! This job you left me" he pointed to an angle iron bracket all marked out

and inscribed with the instruction: 'Drill four holes 16/32" diameter'

"I can't find a sixteen thirty two drill, will fifteen thirty two do?" Barrow

feigned astonishment:

"No sixteen thirty two drills!? What's this place coming to?"

"I can't find any. I've been right through the cupboard - twice."

"Do them half inch then Albert" said Barrow.

Soon the place was empty; they were all out on the plant. Broomie walked to the

door as if taking the air, looked round casually then dashed back to the drill.

The exposed corner did have the familiar green whorls and bulges and even what

looked like a picture of the Queen; the rest of it, however, shouted in big red

and yellow letters: 'Win a thousand pounds in the fabulous Nescafe Grand Prize

Raffle!'

Towards the end of the afternoon Barrow and his team, Owen the labourer and

Trellie the apprentice, came out of the Benzine Hexafluoride and passed through

the Bagging Plant on their way to the Brewtime A-Go-Go. The Bagging Plant was a

cavernous steel-framed building with high grey windows. Sparrows flitted in its

vacant upper regions. Down below forty massive stitching machines clattered and

whirred, each one operated by a woman in a blue smock. They were young, old,

fat, thin, pretty and ugly; a really exciting collection if you weren't too

squeamish. Big Irma was middle-aged, fairly fat and pretty ugly. They collected

a parcel which Barrow paid for by going into an enthusiastic clinch. Irma's

vast, rubbery lips jammed up against his like a plumber's squeegee while

Barrow's grimy hands sank into her bulging buttocks. Pandemonium, a human

cacophony, rose above the mechanical din. Trellie, feeling like general Custer,

looked round for something to back on to. Was this Pompeii just before the

volcano blew? Barrow had warned him never to go through here alone; he reckoned

they'd have his pants off. The embrace collapsed with great stagey gasps on both

sides. Cheering ensued and Owen and Trellie moved on in safety while Barrow went

over to a young redhead in the corner. The ribald rowdiness subsided and

although there wasn't an eye in the building which didn't glance over that way

the illusion of discreet privacy was preserved.

By the time Barrow arrived Owen was stretched out in the cosy gloom of that

rarely frequented site hut while Trellie poured tea from a big vacuum flask. The

Brewtime A-Go-Go was the Inorganic workshop's private staging post; a cedar wood

storeshed at the far end of the works. Anyone up that way was entitled to take a

break in it. As with finer spirits, moments of elation produced in Barrow an

inclination to declaim verse. It could be Wordsworth or Keats but today it was

that great proletarian poet Anon. He burst through the door intoning:

"She stood on the bridge at midnight

Throwing snowballs at the moon.”

His filthy tin cup looked as if it has been filled with dark mahogany woodstain.

He poured in some condensed milk and three spoonfuls of sugar. This glutinous

fluid was gulped greedily.

"Gettin anywhere with that one?" asked Owen.

"Getting anywhere? Am I getting anywhere? Just ask me if I'm getting anywhere."

"Getting anywhere?"

"I reckon I've cracked it Owen luv!"

"Not before time either. You've been working on it for months."

"Worth waiting for though. What a body!"

"Has she got a sense of humour though?" asked Trellie, "Can she cook?"

"Unfortunately Trellie, in my experience, good cooks with a sense of humour

usually look like Fanny Craddock."

"What's been the big delay anyway?" said Owen.

"Its her old man; mad jealous he is; never lets her out. But he's also crackers

about fishing." Barrow gave a great, cackling laugh and rolled over backwards

along the bench. "And tomorrow night. . .him and his mates. . . are driving down

to South Wales. . .for their once a year. ALL NIGHT SESSION!"

"Jammy sod!" said Owen.

"What if he comes back?" said Trellie.

"And are you definitely on?" said Owen, "Round there? Straight on the job? Up to

the maker's name?"

"Hell no! She's a nice girl Owen, not one of your Cock and Trumpet scrubbers.

We've only known each other thirteen weeks, four days, nine hours. I merely find

myself in a position to take her out for a slap up nosh in one of the district's

most expensive restaurants, and afterwards. . .inflamed by our brandy liqueurs.

. .who knows?"

"What about the missis?"

"No, I'm not taking her as well - be too expensive."

"Well I hope you've got a good story."

"Do they let people in overalls in the Woodlands at night?" said Trellie.

"I'll

bring my best gear in won't I, pillock! Change in work. You'll call on the way

home won't you Owen? Tell her I'm tied up on the evaporators; could be in all

night?"

"Certainly Alan. I'll tell her you're working like a dog - a thoroughbred stud

Labrador."

"What if he comes back?" said Trellie.

"You could leave your stuff in Ron Cornes' locker" said Owen. They laughed.

"That's really weird" said Trellie, "How is all that junk getting in there? I

helped him to go over it again this morning - couldn't find a thing."

"Christ Trellie! I thought you knew!" said Owen, "Its this crazy sod here." He waved his

cup at Barrow.

"Hell!! I might have known. But how?"

"There's my key." Barrow fished out of his toolbag a ground down nail punch.

Trellie examined it critically.

"You could pick a cheap padlock with it, but how do you get round a combination

lock?"

"Yeh! That combination lock!" said Owen with ironic awe.

"You don't even touch the bleeding lock" explained Barrow, "you use it to knock

out the hinge pins."

"Jeezus! The hinge pins! If you could earn a living practical joking Barrow

you'd be a millionaire!"

"That reminds me" Barrow picked up the parcel and unwrapped Broomie's 'jacket'.

It must have been just about the filthiest coal sack in the works; damp, black

grit was compacted into its foul smelling fibres. Irma had cut a hole in the top

and two in the sides and, as a nice afterthought, stitched a label just below

the neck which read, in beautiful embroidery: 'Specially tailored by master

craftsmen for Albert Broome Esquire.'

The lads had all been tipped off about the great jacket joke so it was only

Broomie's eyes which nearly fell out of his head when Barrow came into the shop

with the parcel bulging blatantly out of the front of his overalls.

"For God's sake keep it hidden" he whispered melodramatically.

"Into the cupboard quick!" said Albert looking round for Horace.

"How will you

get it home? You can't go on the bus."

"Christ no!" Broomie and Horace were regulars on the half past five double

decker. They always sat together, even got off at the same stop. ''I'll walk

it!''

"That'd be best Albert. Pity its started raining."

Albert got drowned but reckoned it was worth it. When he got in he took his

boots off, shouted excitedly for a pair of scissors and, with his wife looking

on expectantly, opened the parcel on the spotless kitchen table.

At night-school, in the corridor, Trellie bumped into Ron. He couldn't help

explaining the hinge pin trick. It was a rare pleasure to have his brainy fellow

apprentice hanging on his every word. They had a long talk about Barrow, about

his Bagging Plant conquest, about the great jacket joke, and all his other crazy

exploits. They agreed he was a bit of a nutter and wondered why nobody had ever

done him in return. Ron promised to give the subject some thought in the

forthcoming lesson on hydraulics. The bell went.

There was a lot of shouting next morning as Broomie struggled into his overalls.

Remarks about the jacket; a real, withering barrage. Someone handed him a coal

sack tie to go with it. Albert just kept his trap shut as if they were all

beneath his contempt. The shop emptied as usual; only Ron hung back. He fitted

new, extra-long hinge pins and mushroomed over their protruding ends, then had a

chat with Albert. The rest of the day passed uneventfully. Barrow had a strange

call from the Glauber Salt fridge set building but when he got over there nobody

knew anything about it. It was nearly half five anyway so he didn't hang about.

Soon he was back in the shop, alone in that echoing void of steel and brick. As

always when he stayed late he plugged in the kettle for a final brew. It gurgled

to a climax as he slipped into his finest white shirt with the frilly front and

put on a magnificent yellow silk tie. He imagined the two of them sweeping into

the Woodlands; with a figure like hers she'd look sensational dressed up, the

perfect complement to his own svelte neatness. Bending slightly he combed his

glossy black hair in the mirror taped to the wall. One last admiring glance then

he straightened and took a swig. Strange! He scarcely got a mouthful. Puzzled,

he tipped the half-pint cup even further. Then he felt, with growing rage and

horror, the spreading warm wetness of a huge patch of tea on his chest. Before

he pounded the cup flat with a nearby seven pound sledgehammer he looked in

amazement for its secret. Just under the overhanging lip, on the mouth side of

the handle, somebody had drilled, with loving precision, four adjacent one

eighth holes.

By that time Broomie was miles away, on the bus as usual; next to his old mate

Horace, front seat, top deck. He looked more like Monty than ever, bolt upright,

staring straight ahead with a new hint of perky aggression. He could have been

rattling into Tobruk on top of a Churchill. His lips were slightly pursed.

Horace could just hear, faint and low pitched, the sound of Colonel Bogey, that

jaunty symbol of the rebounding underdog.

Ken Clay

(Warrington)

THE GRAVEDIGGERS

I asked them what they were digging

The two young labouring men

And they laughed and they joked and they jeered

As they leaned on their spades and said

We're digging for England mister

For England

That's what they said

I'm digging a grave for the blacks, mate

And I'm digging one for the reds.

Their other companion joined in the jokes

Smiling down from the edge of the grave

And over his shoulder he carried a gun

While the other two wielded the spades.

And the labourers joked and they jeered

As they swung their spades over their heads

Throwing the brown earth skywards

Working for England they said.

And as with backs bent they completed

The grave for the blacks and the reds

The gun of their companion now pointed

At the back of the gravediggers' heads.

Bert Ward

(London VOICES)

PARTED

We were parting

for the first time,

she to parents

and I to mine,

for a brief spell

we understood,

too long by far

for newly-wed,

so we smiled to

conceal our hurt,

and as the train

drew us apart,

I ran to catch

some small crumb

for comfort when

she was gone;

what she said is

anyone's guess;

all I heard was

-"and turn off the gas."

Bill Eburn

(London VOICES)

LETTERS

Gillian Oxford writes:

One rewarding way of expanding interest in working-class poetry is by following

the example of London VOICES Workshop. The group collaborated with Sue Challis

who edits the lively journal of NUPE in organising a poetry competition. Six

gift tokens were awarded to those considered best, but many other poems were

published in the NUPE journal during the course of the competition. Twelve of

the poems sent in, including the six winners, were published in the last issue

of VOICES. The total response was unexpected and very encouraging in its size

and quality. About 60 people sent in poems over a period of three months and Sue

still receives the occasional unsolicited poem. She is considering running

another competition.

The TUC Arts advisory committee has been pressing the Arts Council to take the

worker-writer movement seriously as a developing expression of the culture of

working people. VOICES, now the official magazine of the Federation of Worker

Writers, is an ideal vehicle for the expression of working people's experience,

especially at a time of huge anti-union treatment by the media.

Trade union journals who want to interest their readers in a new line of

communication as old as the hills should contact VOICES or London VOICES Group

(address below). Anything could happen. Mass poetry meetings might become vogue!

Gillian Oxford

70 Holden Road

London N12 7DY

01-4450090

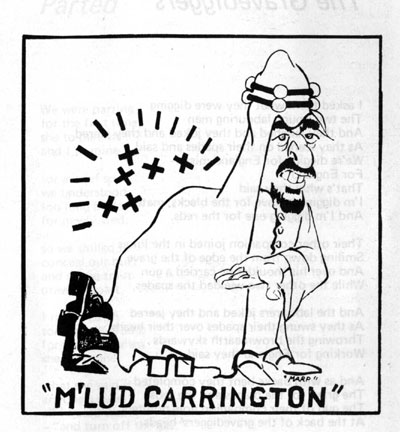

Sean Damer writes:

Dear Friends and Comrades, I am writing as a reader, supporter, and sometime

contributor to VOICES to

protest strongly about the inclusion, of the 'Ayatollah' cartoon in the last

issue of the magazine.

I take gross exception to this cartoon on two grounds: (i) it is racist; (ii) it

indulges in the "cult of the personality" Let me expand. In the first instance,

the cartoon is aimed at the Ayatollah and by extension, the masses of Iran whom

he represents. The bourgeois Press of this country, which I do not have to

remind the Board is also an Imperialist one, continuously delights in portraying

the Ayatollah Khomeini and the Irani Revolution in as negative a light as

possible. The former is represented as a nutter, while the latter is represented

as some kind of inexplicable Mickey Mouse phenomenon. I argue that this is

racist precisely because the people of Iran are Muslim as is their culture. It

is easy to make out that the Ayatollah is mad if he does not conform to Western

(capitalist) criteria of what constitutes a responsible" leader. Now you may

argue that it was all light-hearted and that I am being too heavy, etc., etc. I

don't buy that. The cartoon was a cheap-skate attempt to play on the undoubted

racism which is unfortunately endemic in the English working class. It should be

the role of a magazine such as VOICES to actively expose and attack such racism

rather than promote it. Your cartoon would not have worked if you were talking

about, say, a leader of the Provisional I.R.A., or of the Trade Union Movement.

It is in this sense that it is racist. Let me make it clear that I am not

uncritical of the Ayatollah and the course of the Persian Revolution. But I am

critical of attempts to deride the achievements of a man who after all, drove

the Shah out of the place.

The second ground for criticism must be self-evident: who cares about Rick Gwilt

in Iran? It is the role of all People's Artists to retain a suitable modesty:

they are not immune from the criticism and contempt of the working class.

Doubtless Rick will know Brecht's poem: "Why Should My Name Be Mentioned?" I

hope he has as good an answer as Brecht.

Fraternally,

Sean Darner

(Glasgow)

Rick Gwilt replies:

I don't accept that Bob Starrett's joke at the Ayatollah's expense was racist.

It made fun of the man's particular brand of morality, which is highly

oppressive, especially to women. The man is a butcher, and the fact that he is a

Muslim doesn't make him immune to criticism any more than the rulers of Saudi

Arabia.

I suppose Bob could have been asked to substitute "the VOICES Editorial Board"

for "Rick Gwilt", but of course the Board is equally uncared about in Iran. The

absurdity is the same in either case and is deliberate. The difference is

between a fairly crisp cartoon and a distinctly soggy one.

I appreciate Brecht's poem, even though my own preoccupations tend to revolve

not so much around whether my name will be preserved for posterity as whether it

will still be on next week's payroll. But I do see certain dangers for us lesser

mortals in this kind of self-effacement. The Joe Stalins and Ayatollah Khomeinis

of this world have a habit of riding to power on the back of it, and once they

get there they tend to make sure that theirs is the only name that's mentioned.

I find this kind of "cult of the personality" much more dangerous than any lack

of modesty that I may well have been guilty of by not censoring Bob's excellent

cartoon.

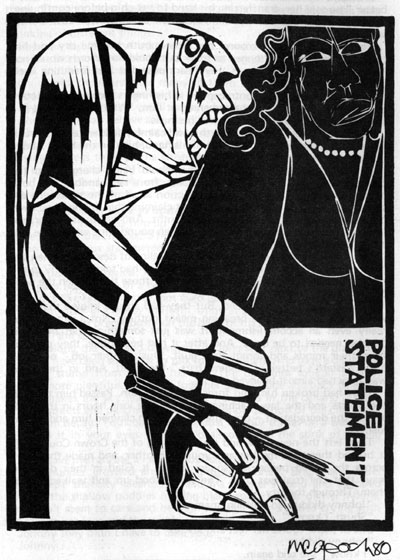

MAD JOHNNIE

They took the least line of resistance. Seeking out the weakest link in the

chain and subjecting it to pressure. She was that link. And she was fragile

enough to yield under the pressure. They used methods of fear and intimidation.

And although they used violence, this violence was considered to be negligible

and so therefore permissible. They needed a signed statement if they were to

have any chance of convicting Johnny. And she was the only person capable of

supplying them with one. The fact that they themselves had written the statement

did not unduly concern them. It was what they wanted and once they had obtained

what they wanted, they discarded her onto the street again. And her loneliness

and her pain were something they chose not to see.

She moved along the street easily. Lamplight reflected in her hair. Heels

tapping lightly on the broken paving stones beneath her feet.

"Carrie."

She did not hear her name called at first so did not stop but continued on her

way. Carefree. Happy within herself.

It came again. More loudly this time. "Carrie." The green mini van pulled onto

the kerb. The driver climbing from his seat and coming to stand beside her.

"Vice squad," he told her. "We're going for a ride." And that was all he said

before taking her by the arm and roughly manoeuvring her into the passenger seat

of the van.

They drove in silence. Through the dark and deserted streets. Drove that way for

what seemed to be several minutes but which she knew to be much less.

In time they arrived at their first destination. Not the police station however,

but the car park behind the football ground.

A sign read: Turnstiles F & G. Adults five shillings, children two shillings.

Fear moved within her.

He leaned towards her but did not speak. Clutching the soft flesh of her leg

above the knee, causing her to shrink into the furthest corner of the seat and

to begin fumbling desperately for the release catch of the door.

His hand tightened warningly, painfully, and she became still. "That's better,"

he told her, transferring his hand to her chin before continuing. "I need

something from you." And then deceptively, "Just a little something."

The night closed in around her. Her mouth became dry and her throat constricted.

She longed to speak but could not. Words would not form themselves into sounds.

Her heart pounded and breathing itself became something difficult.

And then she saw the contraceptive in his fingers and fear completely

overwhelmed her so that she screamed at him. "Why! Why!" And in a sudden panic

lunged at his face with her nails.

But he had been prepared for this and calmly, deliberately he struck her a

stunning blow with the heel of his hand, high on the head. Above the hair line

where it would not show.

Afterwards she only vaguely remembered being charged and the contraceptive and

her money being taken from her handbag and both being confiscated. She had no

recollection at all of the statement she signed and which was produced in court

claiming that Johnny had lived off her immoral earnings for twelve months. And

her own appearance in court the following morning and her ten pounds fine were

more of a dream than a memory.

She remembered always, however, her feeling of desolation when she had returned

to the flat and learned that they had taken Johnny in the night. She remembered

it always. Except for those times when the wine or the drugs brought oblivion.

They broke him in the end. But they had always known that they would and somehow

the breaking meant nothing. Not a victory. Not really even an accomplishment. It

was just something that they had decided needed to be done. And after it had

been done, they drove it from their minds and forgot their guilt. "Just another

job," or, "The black bastard's better off behind bars," they said. And in their

own way they had almost believed it.

They had broken him and forgotten about him. Passed him through the courts and

the law machine. Through the long hours in the dock and all the degradation -

until the silent prison claimed him and he was lost.

They left the new brick and glass building of the Crown Court. Left it behind

them, his mother and younger brother, and made their way across the paved

pedestrian square before it. Glad in their different ways that the trial was

over. The wind stood up and walked beside them. Through the city.

"Johnny diddun do nothing, man."

"Shush, I know."

Bits of paper round her feet and ankles.

"Johnny diddun

"I know," she said again.

The wind moved the clouds and made the cold sun shine down on them. Together

they walked in silence. Hand in hand down the long grey streets. Moving between

the people and the tall cold buildings. Thinking of different things.

She counted the days into weeks and months. He counted the cracks between the

paving stones. There were so many! So many that you lost count and had to begin

again and you kept wondering if you ever really would know just how many of them

there were or if they never ended but just went on and on for ever.

If you tread on a nick you'll marry a brick.

They said if you behave son, you'll be out in two years.

The clouds were black now and angry looking. The wind became restless and ran in

and out of the bus shelter where they now stood, stinging her legs through the

cheap nylons she wore. She buttoned her coat up to the collar. A thin blue coat

that couldn't keep the cold out and if one looked closely enough at the hem, big

black stitches showed where it had been taken up.

"Upstairs, Main! Let's go upstairs!"

Slowly she followed him up and walked down the empty upper deck to the front so

that he could hold the rail and drive.

The big red bus stammered and squealed before gliding out into the traffic.

"The park gates please."

He gave her change of a two shilling piece. Dirty finger-nails. Broken.

"Looks like rain," he said, not even looking out of the window at the sky. A fat

man in a greasy uniform, shiny at the cuffs and pocket flaps. His hat balanced

precariously on the back of his head.

"Yes," she said.

Back along the bus and down to the long seat next to the platform. It would have

been someone to talk to, he thought. And took a crumpled cigarette stump from

behind his ear. The buildings looked smaller, dirtier, more plentiful. Huddled

together side by side and back to back. Smoke makes the sky black and there were

rats in the cellars. A maze of little streets and patchwork houses. A whole

section of the city going to ruin. In decay. You could feel the dust in your

throat on a warm dry day, feel it in your eyes. You could almost taste the stink

of rotting people.

They said the rats ate a Paki's baby half to death.

The thunder growled and the lightning flashed. Bright and blue. Rain swept the

city clean. He held his mother's hand and stamped through the shallow puddles

making black spots appear on her nylons. She didn't seem to care and he didn't

notice that she was crying with the rain in her face and the wind in her eyes.

Johnny they didn't have to take you.

Johnny…..

They hadn't known when they had locked out his day that shadows would creep into

his mind or that dreams would make his eyes blind to the dreams of reality. And

even if they had known, would they have dared to change the order of things?

They made him strip and pass his clothes piece by piece through the gap in the

side of the open-fronted cubicle in which he stood and, when he was naked turn

around and raise each foot in turn to ensure that he was not concealing anything

between his toes. Then he was given a towel and told to take a shower.

He moved as if in a dream. Oblivious to the water's warmth and the muted droning

of the prison warder's voice from beyond the shower room. His actions

unconscious. Automatic. Deliberate and slow. Already resigned to the weeks and

months of meaninglessness that stretched ahead of him.

The prison had absorbed him. As it had absorbed thousands and thousands before

him. Some struggling. Others passively allowing themselves to be controlled by a

word or gesture from another. Incapable of challenging the hold which the prison

sought to place over them.

Finding that their self-belief and confidence had been stripped from them along

with their clothes and possessions, they would close their minds in a reflex

protective action against the harshness and the hurt and enter into a state of

shock and non-awareness. Until, the period of vulnerability having passed, most

would gradually return to something approaching their former selves. Would

slowly make their way back to a strange but no longer terrifying environment.

But there were also others. Those who would never completely re-emerge from

their catalepsy. Who would withdraw too deeply to be able to find their way back

again. Or who would find that within the deeper regions of their minds there

existed a freedom different from any that they had ever known before A freedom

which made no demands upon the individual. At least no demands comparable to

those which reality could and would place upon them in such a place.

After he had showered he was issued with coarse grey clothing and a pillow-case

containing all of the articles that he would need and told to check its contents

against the list on the blackboard at the far end of the reception room.

When he had done this he took his place alongside the others at the tables

provided. He spoke to no-one and neither did they attempt to speak to him -

respecting his silence and understanding his need for solitude.

He thought of many things and yet somehow contrived to think of nothing in

particular. Sitting there staring blankly into emptiness. Time had no real

significance. Passing unnoticed. Unmeasured despite the clock on the wall.

Eventually however they were told to stand and collect a bed-roll of blankets

and a chamber pot each before being shepherded into prison proper.

Here, there were four wings built to a starfish pattern. Each tentacle radiating

from a round central body. Each wing consisting of four landings with wire

safety netting strung across the lowest level.

They were brought to the centre circle with its large hexagonal grating

blackened and polished and made to stand in a semicircle around it. Their

bedrolls at their feet.

Here at the heart of the prison there was a strange tranquillity. Almost a

cathedral-like atmosphere, created by the high domed ceiling and the dim

recesses only faintly illuminated by the candlelight effect of the old fashioned

gas lamps which hung upon the walls.

A few of the prisoners began to talk quietly among themselves, heads leaning

together and - hearing their whispers - he momentarily came out of himself into

an awareness of the prison and its uniformity.

His eyes followed the cell doors along each landing. Painted pale blue. Brass

handled. Every door with its peephole and two large bolts. Every cell with the

occupant's card at eye level giving details of age, sentence, religion and any

special notes concerning diet. Every landing with its catwalks and metal rails.

And as he saw these things and understood their implications, he let his mind

drift back again. Along all of the cell doors and the landings and the rails and

into the centre circle with its heavy metal grating and the new prisoners each

being led to different cells in different wings. And still his mind drifted

back, back beyond the prisoners and the prison. Beyond the world of time and

place. And finally beyond himself.

Until he was locked in his cell and there was nothing again.

They called him Mad Johnny, now, Johnny because that had been his name for as

long as anyone could remember - and Mad because since his release from the

prison and the hospital there was really no other way to describe him. But

no-one feared his madness. No-one feared the violence that his body was capable

of. Even after Winston had pushed him from the cafe and threatened him with a

knife causing Johnny to butt him in the face and knock him almost unconscious

-still no one feared his madness. And that was as things should have been

because Johnny was not a violent man. Was not someone who needed to be feared.

The sun threw shadows upon the wall. High above his head dust motes floated

silver bright in the shafts of sunlight. He rose from the floor of the derelict

cinema in which he slept and made his way into the alley at the rear to urinate.

Weak sunlight bathed him and he laughed aloud and delighted that the damp patch

he had made upon the wall should resemble a running horse because today he too

would run - as he often did. Run through the empty streets and along the

parkway. Around the park itself and then back into the quiet streets, deserted

except for the odd person making their way to work.

But as he ran his happiness slowly evaporated. Deep and dark thoughts came to

trouble him. Images of long ago. Faces that he had forgotten appearing like

ghosts from the past. Insistent. Haunting. Forcing him to reluctantly

acknowledge that he had known another life and with this involuntary admission

came other images. And the pain which he had so long kept submerged.

- They had come into the cell silently. After his anger had spent itself, and he

lay on the cell floor bleeding from a self-inflicted head wound. Two prison

officers and two medical orderlies. He had offered no resistance as they had

stripped him of his clothes and shoes and fastened him into a straight-jacket.

He had been oblivious to all that had happened to and around him. Then they had

led him from amongst the debris of broken furniture and glass that littered the

floor and had taken him to the hospital wing where he had been placed in a

padded cell.

His feet beat the pavement rhythmically as he ran effortlessly through the early

morning city. Sound reached him. Traffic and birdsong. But his brain did not

interpret these noises. On he ran. A flood of thoughts filling his head.

Hurting. Hurting in the heart of him. Seeing little. Recognising even less. And

still he ran.

- He had wept and become incontinent. Cowering in the corner of his cell. Unable

to move his arms. Knowing only fear. Fear of things that he did not understand.

Screaming in his confusion. Yet no one had come. Screaming until he had

whimpered. And still no one had come.

-Thoughts, images, pictures tumbled into his mind. A speeded up still-movie projector focussed on the borderline of delirium. Sweat sprang from his

forehead and rolled down into his eyes. Blurring his vision.

- And then they had come. And then he had slept. -"No," he cried aloud, "No! No!

No! No! No!" His legs were heavy

now and tears and sweat stung his eyes until he could no longer see. And still

he ran. Forcing his legs to move ever forward. Seeking to escape the pain which

exploded within his head. But there was no escape. And so he stopped running and

stood still.

- They had asked him questions. Questions which he had been unable to answer.

Sometimes had never heard even. But they had still asked them. Until eventually

he had withdrawn into silence and had not heard at all. When that had happened

they had sent him to a place where he had been safe and happy. And then they had

returned him to the world. And he had become frightened again. -Pain and

confusion filled his mind to overflowing. His thoughts were no longer coherent.

No longer tolerable. Past and present were inextricably woven together in

strange and terrifying patterns from which he sought desperately to escape. But

he was already without the strength of will and personality required to effect

such an escape and so, in an alarmingly short space of time, the suffering which

his brain was unable to handle or to understand reduced his body also to

ineffectiveness and immobility and he sank onto the grass verge between the four

lanes of early morning traffic.

Later they were gentle with him. Not truly understanding his anguish or its

cause but recognising and responding to another's need. And so, draped in a red

blanket, they guided him into another phase of his life. One which has to know

no end.

Kevin Otoo

(Commonword, Manchester)

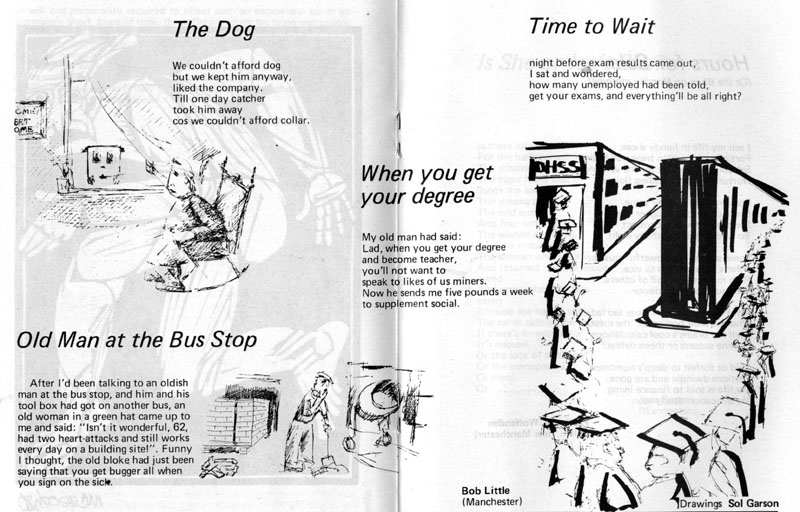

THE DOG

We couldn't afford dog

but we kept him anyway,

liked the company.

Till one day catcher

took him away

cos we couldn't afford collar.

OLD MAN AT THE BUS STOP

After I'd been talking to an oldish man at the bus stop, and him and his tool

box had got on another bus, an old woman in a green hat came up to me and said:

"Isn't it wonderful, 62, had two heart-attacks and still works every day on a

building site!". Funny I thought, the old bloke had just been saying that you

get bugger all when you sign on the sick.

TIME TO WAIT

night before exam results came out,

I sat and wondered,

how many unemployed had been told,

get your exams, and everything'll be all right?

WHEN YOU GET YOUR

DEGREE

My old man had said:

Lad, when you get your degree

and become teacher, you'll not want to

speak to likes of us miners.

Now he sends me five pounds a week

to supplement social.

Bob Little

HOURS FOR SALE

(Or the Blues on Monday Morning)

I sell my life in handy slices;

Portions wrapped in treasured hours.

School prepared me for the vending;

Nurtured all the budding flowers.

Portions vary in their value.

Some command a higher rate.

I was issued with a contract

To weekly sell just thirty-eight.

Some sell skill or powerful muscle.

Others, injured turn to vice.

Rich men use the toil of others.

Manipulation their device.

Am I not worse than those sad ladies

Who sell their bodies for 'the meat?'

I sell my brains's cool calculations.

Is mine success or theirs defeat?

Sold or forfeit to sleep's numbness,

Portions dwindle and are gone.

My life is sold to finance living.

My allocation dearly won.

Pauline A Wolfenden

(Irlam nr Manchester)

IS SHE OR ISN’T SHE?

Is there an excuse

For the halfhearted meals

The missing sock.

The eager hand that

Stops the song of

The singing clock,

The odd curse

And four letter word

The wished dead dog

And the missing purse.

The woman who went out

And returned like the bacon

cured

And cried when she was

eaten

Because she hadn't seen

The other side of the moon.

If there's an excuse

It's misuse!

Or the lack of applause!

Or the menopause!

Or men!

Or ……

Jean Sutton

RHONDDA DAWN

Winter haze

into the dawn

our eyes walk

ice-fingers pointing

to the smeared white

around sunrise hills

to the silhouette fern

& heavy black rocks.

'Here is our home'

u say, your cold tears

breaking the dust-breath

onto the lorry road.

I laugh at your sentiment,

& u seeing no rusting mines

no broken voices of coal-dust men

nor lost bones from songless chapels.

Yesterday,

there was no dawn

only black rain

from freezing of winter

only the soot

from your midnight cough.

Blackie Fortuna

(Oxford)

OPEN LETTER TO MELVIN BRAGG

Melvin Bragg esq., Barbara Shane,

Chairman, Literature Panel, Chairperson FWWCP,

Arts Council of Great Britain, 123, Logan Towers,

105, Piccadilly, Liverpool 5.

London W1

16.6.1980

Dear Mr. Bragg,

We are once again approaching the Arts Council Literature Panel for money for a

national co-ordinator and literature promotions worker. In spite of past

refusals - based we believe in error and prejudice rather than in malice -, we

do not yet despair of receiving fair treatment at your hands. In fact we hope

that you will take the opportunity of correcting an injustice that has lingered

over two years.

As is now well known the Federation is a national organisation which has grown

to comprise some twenty-four writers' workshops and community publishing groups

concerned with furthering the cause of working class writing and community

publishing. The focus on working class writing - a term broadly rather than

narrowly interpreted - has frequently been explained and was a response to the

serious neglect of the literary creativity of a very large section of our

population. We note, as you must have, that it has given no grounds for disquiet

in a specialist adviser commissioned by the Arts Council itself. We note too

that the neglect of which we complain (and about which we are trying to do

something, not without success) was tacitly acknowledged two years ago by the

Arts Council in its decision to grant £2,000 towards the publication of our

first anthology, WRITING.

It is also well known that the post of national co-ordinator is an integral part

of the Federation's structure. It is through the co-ordinator that the often

financially frail workshops and publishing groups are kept in touch with each

other, provided with an information service, advice and support. It is through

the national coordinator that new groups are identified, advised and brought

into the supportive framework of a movement. It is through the co-ordinator too

that groups and individual writers are brought into touch with opportunities for

furthering or developing their work.

The success of the Federation as an organisation for helping working class

writers does not seem to be in dispute. In recent years nearly 200 titles have

been offered to the public with sales somewhere in the region of half a million.

Public readings have been held, meetings and conferences organised, radio and

television programmes made. Partly for this reason the Gulbenkian Foundation has

been willing to give generous financial help, including the underwriting of the

coordinator's salary for a year on the assumption, which regrettably turned out

to be incorrect, that the Arts Council would match the contribution.

The Federation's success has been recognised within the offices of the Arts

Council itself. Mr Charles Osborne, Literature Director, commented in December

1978 on the "growing strength and scope of community publishers and writing all

over the country". And Mr Blake Morrison, a Poetry and Fiction Editor for the

Times Literary Supplement, who was commissioned by the Arts Council to give an

objective assessment of, inter alia the work of the Federation, has quite

unequivocally described it as:

A useful co-ordinating agency in one of the few growth areas of contemporary

literature.

and has urged the Arts Council to consider "with greater thought and care" than

hitherto subsequent applications for funds.

Reasons for the Arts Council's resistance to the Federation applications are

something of a mystery. In a letter of December 1978 already quoted Mr Osborne

wrote in somewhat patronising terms to say that the Literature Finance Committee

was not convinced that the Federation's productions were of "solid literary

value". This judgement was repeated in much the same terms after Federation

representatives had met the Literature Finance Committee in March 1979. The

committee, apparently unanimously, decided that the Federation was 'successful

in a social, therapeutic sense, but not by literary standards". What these

literary standards are and who is applying them and whether they are always

applied (or only to some organisations) remains obscure and there is a suspicion

that standards and the aesthetics underlying them are not much debated in Arts

Council meetings.

In fact the only person connected with the Arts Council to make clear the

assumptions by which he judged the Federation's work has been their specialist

adviser, Mr Morrison. Mr Morrison's report on the work is admirably thorough. He

finds it of varying standard but is in no doubt that a great deal of it displays

sufficient merit to deserve Arts Council support.

Mr Morrison's report with its essentially favourable judgement on the Federation

and its member groups has not yet been published. We find this strange given the

debate over standards currently taking place.

Mr Morrison is not alone in finding literary merit in the output of the

Federation's members. For example, in a recent article in The English Magazine,

Mr Gerry Gregory of Shoreditch College applies traditional literary-critical

standards, and comments:

while you will find much that is dull, flawed and frankly poor, you will also

find as much to admire as in any other reasonably comparable body of writing.

There is no space here to provide examples of a sufficient length to demonstrate

this - and fragments do not meet the case. However the Arts Council of Great

Britain verdict must surely surprise anyone who has read, say, Joe Smythe's poem

"When the Soldiers Came" (Voices 19), Ken Clay's short story "on the Knocker"

(Voices 15), the Strong Words' documentary publication Hello Are You Working?,

much of the work that has emerged from the various projects within Centerprise

(Hackney), and practically anything produced by the Scotland Road Writers'

Workshop.

And Raymond Williams, writing in the Times Literary Supplement of 6th June this

year has this to say in a piece, "The role of the literary magazine":

What has been happening for twenty years in the geographical area that we call

the British mainland has been the

emergence of some new kinds of writer and writing: for example, among many

others, the Lifetimes pamphlets, the Centerprise publications, the Writers and

Readers Cooperative.

Much of this work is still finding its way; in some cases literally finding,

trying to find its forms . - - - The most important function of literary

magazines, within the existing and increasing cultural hegemony, is to provide

many openings for experiments, for first attempts, and then for collaborative

exchange and experiment: the processes from which real identities, as distinct

from the competitive shortcut to a market identity can come. Thus I would rather

see a hundred magazines of this kind - and really a useful number would be in

the thousands - than three our four new London or axis glossies

Instead of this producing a change of attitude by the Arts Council, it seems to

have led to a new excuse for rejection. In a recent letter to a Federation

member Sir Roy Shaw has argued that the applications were “rejected not because

our literature advisers thought that none of your members capable of writing

anything of merit, but because the need for someone to be engaged at a fee to

stimulate people into writing was not regarded as valid."

Yet the Arts Council has spent considerable money on schemes aimed at

stimulating people into writing: what else are the various writing grants,

projects for writers in residence, writers in schools and the National Poetry

Secretariat all about, to name but a few? Sir Roy also gets wrong the functions

of the national co-ordinator who was not employed to stimulate writing where the

impulse was weak but rather to assist working class writers of strong impulse

and few resources, by providing advice, support, opportunities for readings, and

contact with other writers, publishers, persons and agencies concerned with

publishing and distributing new work. However we are intending to appoint a

literature promotion worker. The reasons for this appointment will be evident

from the enclosed job description.

Later in the letter Sir Roy argues that the problem in Britain lies not in

getting people to write but in getting people to read, a formulation also

popular with Mr Osborne who astonishingly wrote to another of our members in the

following style:

It may seem to you unfair that some people are more talented than others, and

indeed it is unfair; however it remains a fact that talent in the arts has not

been handed out equally by some impeccably heavenly democrat. You are right to

think that the Arts Council views itself as a patron of the arts. This is indeed

our function. It is important that we do all we can to increase audiences for

today's writers, not that we increase the number of writers. (Our italics)

Not only does this miss the connection between creativity and consumption

(writers are readers) but it ignores the extent to which the Federation has

opened up markets for not only its own work but literature (and theatre) in

general.

We feel obliged to point out that we have patiently been seeking assistance from

the Arts Council since the first half of 1978 and that in that time have tried -

at some expense - to meet every request for information about our organisation,

for examples of our work and for submissions and resubmissions. We have no wish

to quarrel with the Arts Council but its response to us seems to have been

evasive and patronising throughout: as we meet each objection raised, another

seems to be found. We are forming the impression that the real objection to us

is not based on the quality of our work but on the fact that we are concerned

with working class writing and that our methods of encouraging writers are based

on workshops and collectives rather than on the traditional concept of the

artist-in-a-garret. In reply we quote your specialist adviser, Mr Morrison once

again:

FWWCP's attachment to 'working class writing' has, I know unsettled at least one

member of the Arts Council's literature panel, who felt that this was a sign of

political rather than literary ambition. I do not think that this distinction

holds. To encourage the growth of literature in a section of society which for

various social and economic reasons, has not yet made a proportionate

contribution to literary culture - this is a literary as well as a political

function.

We find it rather disquieting that the decisions taken to refuse us funds are

seemingly arrived at by a very small group of people. We have a certain amount

of evidence that very few judges of literature in the Arts Council have had a

chance to assess our work - in spite of our willingness to make it available. We

have all along made it clear that we are willing to debate - in private or in

public - the quality of our work and the principles of our organisation.

In conclusion we would say this in great good faith: surely the time has come

for the Arts Council to put aside the past, to act in the spirit of its

specialist adviser's report and treat us justly in the way we ask? Surely there

can be little objection to giving a few thousand pounds for a few years to an

organisation which is demonstrably enriching and widening participation in

literary culture on a variety of levels? We can understand, though we do not

approve of it, the kind of thinking which has traditionally made the Arts

Council the patron - with a few exceptions – of a generally privileged minority,

the talented middle class and its societies and institutions. We would not

trouble the Arts Council if we had other sources of funds. But we don't and our

financial position is parlous. The Gulbenkian Foundation which has so generously

assisted us for years can do so no longer. The working people of this country

are the major contributors to the financing of the Arts. We ask that some of

their money be used for them.

THE WELDER

(for Jack Davitt)

Welder! Welder! burning bright

On the scaffold of the night,

What immoral company

Dares write off your poetry?

For what wages or what prize

Burned your cheeks or dimmed your eyes?

With what needs did force conspire

To bind your hand to seize the fire?

And what promise or what art

Could stop the knowledge in your heart?

And when your hand began to write,

What hard graft? and what hard fight?

What the jobs? and what the men?

In what piecework was your pen?

What the fumes? and what the sweats

Ne'er forgives it nor forgets?

When all the Tyne is closing down,

And no more the buzzers sound,

Will they cost you one more laugh,

Commissioning an epitaph?

Welder! Welder! burning bright

On the scaffold of the night,

What immoral company

Dares write off your poetry?

Rip Bulkeley

(Oxford)

FOOTBALL PINK

There was still half an hour of the F.A. Cup Final left as Tommy pushed his

way through the crowd to the nearest exit. Although there was no score, it had

been an exciting, fast flowing, end-to-end game, with plenty of near misses by

both sides. But Tommy couldn't concentrate on the football. His mind was on

other things. His thoughts were full of jellied eels, fish roes, and frog spawn.

He had been warned about having the prawn cocktail travelling down on the

British Rail Football Special, but, full of high spirits, he had devoured the

noxious substance with scant regards to the consequences.

He made his way to the flight of steps leading down to the toilet and bars

underneath the main stand.

How he managed to struggle through the massed throng he didn't know. He found it

extremely difficult to keep mind and body together. His thoughts kept shooting

off on strange tangents, rushing so fast that they were scarcely registering.

He took a deep breath, and tried to estimate when the horrific effects of the

prawn cocktail would begin to wear off, but time, as he vaguely sensed he once

knew it, somehow no longer had any meaning.

He stood at the top of the stairs, looking down into the pitch darkness below.

The steps seemed to lead down for miles, right down into the bowels of the Earth

itself.

He gripped the handrail tightly, and gingerly descended the steps.

At the bottom he rested against the concrete pillar that he took to be holding

up the entire Universe.

I wish I'd have stayed at home in Huddersfield and watched it on television, he

thought to himself, as he stared at the group of penguins standing at the bar

dropping miniature icebergs into their glasses of sardine juice. He closed his

eyes to blot them out.

The acrid smell of camel dung burned his nostrils as he walked through the

turnstiles leading out of the stadium.

The rattlesnake with the Traffic Warden's hat perched upon its head hissed

threateningly at him as he walked down Wembley Way. He scurried quickly past it,

giving it a wide berth in case it should decide to sink its venomous fangs into

his exposed lower thigh. He mentally chastised himself for being so foolhardy as

to have worn his safari shorts for the trip down from Huddersfield.

'An-i-muls! An-i-muls!' He found himself involuntarily shouting at the two

hyenas in police uniforms. The hyenas paid him no heed. They were far too busy

moving on a herd of water buffalo who were causing an obstruction on the

opposite side of the road.

Deciding that the- safest place would be home, he made his way to the elephant

rank.

He wearily climbed the platform, and mounted a vacant elephant. 'Home Jumbo, and

step on it!' he told it. The elephant set off at a brisk pace in the general

direction of the Ml.

Tommy was feeling a little better as the elephant pulled up at a set of traffic

lights on Wembley High Street. He was now regretting leaving the match before

the final whistle, but he appeased himself with the thought that there are some

things a mere mortal has no control over.

'How did the Cup Final fish up?' He called down to the wildebeest selling

newspapers on the street corner.

'Why don't you buy a paper and find out, Bwana?' The wildebeest shouted back at

him.

Before he could think of a suitable reply, the traffic lights had changed to

stickleback, and the elephant had galloped around the corner.

Tommy's heart sank as they came to the traffic jam. The road was full of rhinos,

packed solid nose to tail, impatiently stamping their feet and honking their

horns.

'There's nothing else for it,' Tommy said, 'we'll have to fly the rest of the

way.'

The elephant flapped one ear in preparation for a vertical take-off. It tilted

slightly sideways.

'Both ears, you fool,' Tommy screamed, as he slid down the side of the elephant

and pitched headlong into the gutter. The elephant responded immediately. Tommy

sat on the edge of the kerb, and watched it fly off over the rooftops.

'Bloomin' cowboy elephants,' Tommy muttered to the rhino who pulled up alongside

him. The rhino snarled at him. 'How did the match crow?' he asked, changing

tack. The rhino turned towards him, lifted its nearside front leg, and made to

bring it crashing down upon Tommy's unprotected head. Tommy shut his eyes, and

froze in sheer terror.

A mighty roar caused him to open his eyes. He-found himself leaning against the

pillar beneath the main stand. He looked up to see four blue-and-white-scarved

Town supporters, arms around each others' necks, staggering down the steps

towards him.

'Eel-eye-haddocko, we've won the chub,' they were chanting in unison

Tommy let out a sigh of relief. The heady effects of the prawn cocktail were

wearing off at long last.

'How did we go on then lads?' he asked, as they brushed past him.

'We won 3-0. Didn't you see the match?'

'Had a bit of toilet trouble,' Tommy said, holding his stomach with both hands,

'I missed the last half hour. Who scored the goals then?'

'Shark got two, and Sturgeon got the last with a penalty,' the lad called over

his shoulder, as he staggered towards the bar.

Another loud roar went up.

Tommy raced up the flight of steps to the bowl of the stadium. He was just in

time to see the Prince of Whales presenting Jimmy Herring, the Town's kipper,

with the F.A. Cup.

Facing the crowd, the popular veteran balanced the cup expertly upon his head.

Almost every one of the hundred thousand seals throughout the stadium barked

their approval, and smacked their flippers together in sheer ecstasy.

Tommy felt a lump rising in his throat, and tears welling in his eyes. It was

the proudest moment in his whole life. They'll be cracking open the prairie

oysters in Huddersfield tonight, he thought to himself, as the victorious team

dived into the moat to begin their lap of honour.

Michael Rowe

(Commonword, Manchester)

THE RITUAL

On Fridays, when he feels rich

Has renounced the muck and aching limbs,

The tedious shifts of another week, he

Lurches in, fumbling for the porch switch

Drunk as an empty sack,

With bits of old songs to let drop.

His escape is crumpled, short-lived;

A wife has prepared for the coming back.

She exhumes his dinner at the double

Has hid the children in their beds and

Wrings out safe reproaches in a dishcloth

While he shovels and spills every mouthful.

She, with frantic chores, tries to avoid

The sight of him, hunched and staring,

Forearms clamped upon the table and

The thickness of his breathing to dread,

For soon the overtures will be clumsy;

What used to be breathless and mutual

Will be a dumb struggle,

An intrusion without apology.

Tony Marchant

(Basement Writers Stepney London)

THE NORM FORCE

The police are appealing for information on people who

are seen to be acting oddly

(You know the type)

People who:

make love in business hours,

sing in the Bank,

dance to work,

stand naked in the dole queue.

touch the person in the next seat,

sit in the wrong corners,

stand on seats,

stand in the stands,

steal so they don't starve,

shout angrily at the rich,

break down and twitch in public,

burn money,

kiss coloureds,

fight racists,

swim in the Tyne,

drown in the Tyne,

get drunk at the wrong time,

sleep when they should be awake,

undress when they should be dressing,

eat when they should be drinking,

drink when they should be eating,

wear no underclothes under their uniform,

refuse to wear a uniform,

call a weed a flower,

listen to bird-song,

drive to drink,

grow hair and grow young,

try to fly,

laugh too much &

make beautiful and useless things

(That type of person)

Keith Armstrong

BRASSFOUNDERS

Based on a seam of banded ore

and the sweat of migrant labour, -

Motherwell, an industrial hell,

where livings are muscled from men;

Warrant sales to chequer behaviour

wages arrested in front of the mates,

rackrented by worry, reckless of danger,

workers of iron foundered in debt;

wracked by the working in man-made infernos

teamers cast ingots, diced daily with death,

tin pocket labour mouldered in squalor

Founding the Brass of industrial magnates;

Searing flames rendered tough mettle,

flame-dressing flaws from untempered labour,

bringing to boil reluctant soup liquid

Tungsten iced steel wilted distressed;

Steam, oily with venom, hissing in hatred,

scalded the lives of mill operatives,

driving the hands of the light rolling section

banking the forges in Threadneedle Street;

Rollers relentlessly pressing out 'H' beams

taking the joists from our very bones,

taking the bloom from blossoming youth

bankrolling stockholders in metal exchanges;

Yes the coloured motif of a graftin' town

belies a grim existence,

by 'Hand and Brain' the motto proclaims-

a 'Freedom through Work' invitation;

A Pick an' Shovel when the pickings gone

invite to scratch a living,

Obituary columns of clinkered slag

symbolic of debased existence.

Gerald Strain

(Motherwell, Scotland)

THE FRANKLIN STORY

She lifted up the packed briefcase and looked around for what was next on the

list. It was a self-imposed busy-ness: she needn't have taken a job but her day

at home with the child was too much for her. She had to have more stimulation

than that. He was a beautiful child -. friendly, responsive. He stood there now

looking at her with wide blue eyes, playing at the moment with some bricks he'd

found on the floor.

"Oh, what next?" she said, looking around in haste; the busy-ness almost

continued in order to dispel the emptiness about her that even he didn't fill.

The post rattled through the letter-box. She'd just grabbed the door-handle,

about to load his kit and the green pile of marked books into the car. She

stopped for a moment. There was a letter from Chile. She'd have a look. Things

ceased whirling and a cold fear stopped her and numbed her as she kneeled down

to pick up the blue envelope and deposit her load. It was only ten days now

since the news of the coup. She opened the envelope, realising that it was in

Rose's handwriting and read the short note inside. "Franklin was shot, with his

family, early yesterday morning."

She began to cry. Tears streamed down her cheeks though she tried to keep quiet

because of the child. He came toddling round to have a look.

"It's nothing! It's nothing!" she said.

"Mummy! Mummy!" He didn't know who the letter was from even.

"It's nothing, love, it's nothing! I'll be all right in a minute."

He didn't seem to worry much. Mum and Dad scarcely ever let their emotions get

the better of them in front of him. His world was one of peace, at home at

least, though the nursery, to which he was about to set off, was full sometimes