|

ISSUE 21

cover size 210 x 148 mm (A5)

EDITORIAL

Back in 1975, as VOICES was being transformed into the sort of magazine it is

today, the late Ben Ainley argued in one of his editorials that we should not

think of culture as simply 'a weapon in the fight for socialism', but that

socialism meant the creation of a new working-class culture. In other words,

culture is a bit more than the icing on the political cake.

The Worker-Writer movement that has really taken off over the last two or three

years has also embraced this idea of culture. For VOICES this has meant some

changes in the kinds of things we publish. A few years ago there were still a

fair number of 'clarion calls' for action - rhetorical poems that saved the

party or union stalwart the effort of re-thinking the things they already

believed in, while doing nothing to stimulate fresh thought by other working

people. The writing we publish now is no less political: the difference is that

the writers are more likely to be concerned with examining life as they

experience it, and drawing the political lessons from this, than with coining

new slogans.

Another change has been in the way that people write. A few years ago it was not

uncommon to find poems about factory work dressed up in the language of Shelley

or Keats. Today the poems are stronger for being written in the language that

the writers use everyday.

In short, the writers in VOICES today are discovering in their everyday lives

and in their writing the basis for their socialism.

A large part of this development can be put down to the growth of the Federation

of Worker-Writers. Through the detailed discussions and criticisms within the

many writers' workshops, and contacts between different groups throughout the

country, working class writing as a whole has been strengthened.

The paradox is that in this issue of VOICES there are only a handful of pieces

from the 20 or so member groups of the Federation (2 pieces if you take away

those by members of Commonword who are involved in VOICES). If we are to

continue to develop and build up a really national readership we need two

things. First, a steady flow of material from the Worker-Writer movement; and

second, distribution of the magazine in their own areas by local worker-writer

groups.

Phil Boyd

THE MOSS

John Gowling

The summer of nineteen seventy two would not be something I would forget all

that easy. One night I found myself wandering round the concrete mass of Hulme

redevelopment for hours on end. Like the blues song says . . . . I was walking

the back streets and crying.

Must have been 2am when right bang in the middle of the crescent flats you come

out of the gents with your transistor radio and saw this tatty white boy slumped

there against a pillar. I pretended to be asleep. But really I was spellbound by

you, this old black guy doing some gyrating dance and fancy footwork to the

music on the radio. You could see I was depressed and blow me down if you didn't

come over and act the fool just to cheer me up.

You come to tell me of back home, the hurricane that nearly brought down Spanish

Town when you were a child. Your mum and dad had spent the whole night with

their backs leant against the front door. The corrugated iron roofing was

lifting up and down. You were only six years old and you huddled in the clothes

rack terrified. But the storm passed. Then you said how as a child you used to

chase the slow sugar train. The sugar canes would fall from the sides of the

heavy laden wagons and you would chew the sweet cane all the way home.

Then you said how you left home to work in the boiler rooms of the old steam

ships. And how one time you spent all your shore-leave in Durban gaol, South

Africa, for refusing to sit at the wrong end of their stinking trolley bus. And

about the boy who painted his own body red and white to get a job as a rickshaw

boy in the South African city. And as you told me, your rage rang out through

the Hulme night and lights went on for blocks around.

I mean I guess like you were telling me that one has to find a way to triumph

over adversity. You know, the mountain aint steep, the river aint deep. You told

me of the countless times the ship had left you in some foreign port. You were

always too late to up and dress out of some lady's bed. You wondered how I would

cope with being stranded in Rio or the like. I said that I didn't know.

I even come round your house a few times after that. Well, its like this: the

number of white kids that wind up in bedsitterville in Moss Side. And all we

really need is someone to talk to So we get hip into Soul MUSIC with our Black

Motown Detroit bob hats and the way we can northern-drawl a Jamaican accent

better than you can. Yeah but somehow as I was getting to see you everyday you

knew that this meant death by rumour for you . . . to be seen with one of these

very un-hip white kids. There had to be a way around it. So you introduced me to

your wife.

Your beautiful wife, Rowena, with her beehive ginger hairdo, high heel shoes

with straps, and her painted toes. One evening she started up some West Indian

cooking, like you had taught her, and invited in me and Doris from nest door,

and Doris brought along her little boy. We all served each other big helpings of

stew and rice and sweet potato from big bowls in the centre of the table, and

watched John Conteh and Coronation Street on the telly. And after the plates had

been cleared away Rowena flashed round her Embassy cigarettes and sat back to

tell us all how she met you, Delroy, her husband. Rowena started up.

"Well, this was way back in 1945 and I'd never even heard of Moss Side, let

alone set foot here. I'd never even seen a blackman before. No, I tell a lie,

I'd been through it once on the tram when I was a very little girl and there

were these big houses, that's when it was posh, and some old run-down houses,

and there were little children running around in bare feet. In those days my dad

was a publican and we lived in this pub up Bury Old Road. And I was the apple of

my dad's eye. He spoilt me something rotten. You see, I was the only girl, I've

got five brothers.

"Well, I was turned twenty three and I'd never so much as dated a boy. Things

were different then, sex wasn't flung at you from every road hoarding. I was a

virgin when I met Delroy, in fact until we were married. If you made a mistake

in them days, you'd made a mistake, girl. (looking at Doris.) But I didn't want

to do it before I got married. Truth was I wasn't keen on doing it anyway.

Anyway one night me and Maureen from up the road decided we'd have ourselves a

secret night out so we went down the Barbary Coast, that's Cross Lane, a big

street of pubs and clubs that goes up from Manchester Docks to the centre of

Salford.

"That was how I met Delroy, at the Casablanca Club. He was very nice and

handsome and he had all his hair, then. He came over with his ship-mate and they

asked me and Maureen to dance, in ever such a polite way. The way he held me was

like the way I'd seen Clark Gable in the flicks. I knew right then and there

that he was going to be the man for me.

"Listen: every time his ship used to be due in I'd be there at the dock gates;

and I used to sit home by the phone and I'd never let anyone else answer it. My

dad was mystified by the lovelight shining in my eyes. He kept saying how I'd

have to bring home my young man and winking his eye at his only daughter. And

you know, my stomach was in a knot. I couldn't bring myself to tell them. It was

like I wished I'd never even got parents. Cos I had to tell them. To be fair on

Delroy, I couldn't just have him standing there on the doorstep.

"Eventually my mum found Delroy's photo in my dressing table drawer and she tore

it up and called me some awful names. So I got the negative and got a real big

blow-up enlargement of it and put it in a frame on top of my dresser. And every

night when I got home, my mum had taken the picture and put it in the drawer. So

I'd take out his photo again and put it back up there where it belonged, for me

and the world to see.

"In the end I had to leave home because the pressures came too much. My father

wouldn't even speak. So I run away to Liverpool and waited for Delroy's ship.

I'd saved up some money and stayed in a beat-up hotel. At first Delroy called me

a fool for leaving my happy home, but we both knew that things hadn't been all

that happy recently. That same day me and Delroy got married in the Seaman's

Mission. A Nigerian seaman was the best man and a Gambian man gave me away. How

I cried for my mother and father.

"On the wedding night we went to this Somalie club where that wedding photo was

taken (pointing to the wall); (Delroy looks like a gangster in his baggey suit

and Humphrey Bogart hat; and Rowena is decked out in the "New Look" fashion with

a floppy hat and a veil. The picture is mainly tinted green and maroon by the

photo-artist, and the faces are tinted dark brown and doll-pink).

"Anyway, there we were celebrating in the Somalie and blow me down if my own

brother hadn't caught up with us and comes in the club brandishing his war-issue

pistol. Well, I had half a notion to faint, but I held fast. And our Frank

saying how he wasn't going to let his own sister marry a coloured man, and how

he had come to take me home. Well, I stood up, Lord knows how I did it and I

gave him a piece of my mind about coming in here calling folk, he wasn't even

fit to empty Delroy's piss-pot let alone lecture me on what I should do.

(Doris's little boy giggled). I honestly thought he was going to shoot the pair

of us but he was sort of stunned and Delroy and this other guy called Delroy got

the gun off him. And do you know, our Frank sat down, all shaken; and had a

drink with us. And we never had a better night. The way Frank and Delroy got

talking you'd have thought it'd been Frank who'd married him. You see, he'd

never met Delroy before. But once he'd got to know him. .

"So I come home with Frank and my marriage licence in MY BAG. Next I had to get

some place for me and Delroy to stay. And in those days you couldn't even walk

down the street with a coloured man .

(Doris's little boy asked, "Why?" and Doris said: "Hush love, and lifted him up

on her knee and wrapped her arms around him).

Then Rowena continued in a hushed voice about her miscarriages over the

worriness and how Delroy thought he was impotent and they were blaming each

other. And how they finally got this back-to-back house behind the University.

There they were robbed once a week and the police'd never do a thing about it.

Delroy suspected it was all a racist vendetta. At last Rowena gave birth to a

fine baby boy whom they called Leon. As a child Leon contracted T.B. And how can

anyone contract T.B. living right next to the University Medical School?

Leon had to spend half his childhood in Abergele Sanatorium and Rowena and

Delroy had to travel all the way to North Wales to see their little boy. But the

staff at the hospital were very nice and let them stay in a chalet at weekends

with Leon.

At that moment Rowena got all mad and vibrant and started talking about the

Fifth African Congress which was held in Manchester in 1947 and how she'd done

all the typing for Mr. Kenyatta.

"That was the congress that changed the direction for the African colonies;" She

shouted. "Away from colonial rule, towards self determination".

And she recalled how she met Mr. Nkrumah. "Who's Nkrumah?" asked Doris's little

boy, and Rowena said: "If you come in here tomorrow, after school, I'll tell you

all about Kwame Nkrumah and his dream:

Ghana; and about a Mister Marcus Garvey."

So now we are back in 1972, and you, Delroy, tell me about your fine son and how

he has lightened his skin and straightened his hair. And how his girl friend

Sarah has darkened her skin and permed her hair Afro. You tell me how you've sat

alone in the middle room for hours trying to figure out the younger generation.

And now at age fifty seven you walk down the summer-night Great Western Street

in a string tea shirt, jeans and barefoot open sandals, showing us all that

Black is Beautiful. A gang of partying brothers and sisters ride past in a

convertible Hillman Minx and hit on the horn and give Right On clenched fist

salutes.

An orange and white 53 bus swings high-hat round our corner and shimmers past,

swaying from side to side like an illuminated galleon. It brakes at the traffic

lights and an old couple, one black, one white, get down from the centre doors

and cross the road to the Nile Club. It seems like the collage of integrated

life comes all together to create a euphoria in my mind like I've become a new

member of something. And I snap my fingers, move my hips, bend my knees real

low. Then leap up to touch the street wires. Aretha Franklin holds one long

note, then finishes the remaining song quickly as my feet come down to hit the

street like two deep concluding piano notes.

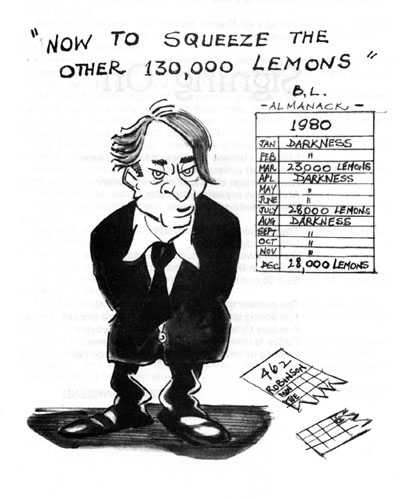

AGITPOEM No 24

EPITAPH FOR THE TOMBE OF THE UNKNOWING SOLDIER

He thought. for king and country, glory, Latin,

honour, medals, fame, applause.

He went: but never knew the cause.

He fought and died, in rich men's wars.

Bob Dixon

CITY SHITFATHERS

u stole our town

with yaw plans

made in shakes

& knowing nods,

built tall bridges

& stepped underpasses

so yaw cars

could move faster,

tore down our pubs

& our halls of laughter

left jus rubble

& fireweed,

shoved uz in queues

at panda crossings

den told uz to vote

for u,

sayin each party

is differant,

& will help t folk

to live better lives

under yaw lies,

but u r all t fucking same,

we it comes to decide,

t rich will have lair way

t rest go get hung –

& u dont pay yaw architect

to do bugger all

& we all know of t sidelines

dat draw u to power,

u dont do it for charity

but to line yaw pockets;

well u city shit-fathers

aint votein no more

den i know i aint to blame

for yaw greed,

& if u r ever caught

den i hope its t same

as i will get if i steal

but den u aint poor

& u aint black

so i suppose it will be

a tut here & there

den all will be forgot

as t next lot of robbers

cums singing blue notes

into office.

Blackie Fortuna

COURT NEWS

I know it's Winter when the papers report

the Queen is away on State business

somewhere near the Equator. When the T.V. news

shows film of a sunnier country

I know what's coming next, the Queen

being greeted at tropical airports by tropical

V.I.P.'s, she's a very busy woman is the Queen,

in Winter. I know it's Winter when

Princess Margaret is reported on a Caribbean

island, with or without some Roddy,

Reggie, Lance, Max, Em, Leeds Jimmy,

and the horn section of Syd

Lawrence Orchestra. I know it's Winter

when the papers throw up this garbage.

Joe Smythe

YUGOSLAVS AT

FRANKFURT STATION

We meet for a drink here

because it is

the nearest thing to home.

We stand, each day the same,

staring across at ourselves,

at the day we all arrived,

exchanging one barrier

for another,

looking along calendar-rails

for a light,

a return

on a hard investment.

We are a flock,

a bunched fist of dusty mechanics,

fitting the bits together,

chewing over bread crumbs of empty gossip

in a station

blown full of anxious people

moving noisily

away from each other.

We ( we Yugoslavs together)

cannot move,

not yet:

we are chained

at the dry end of a railway tunnel.

Across the other side,

in the light of Yugoslavia,

on the bent backs of quiet villages,

it is raining,

watering the seed

we planted months ago

on home grounds

where our children grow

apart from us,

a mere train journey away.

Keith Armstrong

ZIMBABWE

Yes,

You can frame with barbs and hooks

And constitutional safeguards

A form of words sufficient to your eye.

But time will teach you

(like many a fool before)

that a barbed wire fence

cannot check a tide.

Phil Boyd

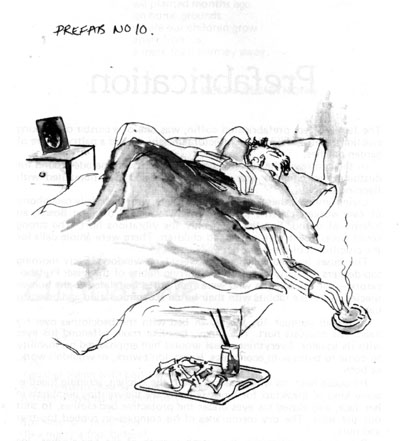

PREFABRICATION

The family-sized, prefabricated coffin, was one of a cluster of creaking

erections that huddled in architectural misery around a paltry square of garden

patches. In the centre of the asbestos group, the restricted parade-ground for

dustbins and children was sparsely green and over-populated with flapping

laundry. Living amongst these residential amplifiers, with their daily cacophony

of over-worked cisterns and citizens, was a kind of aural Bosch, an inferno of

sound. For the deaf, only the vibrations hurt. The strong could always beat

their wives and children. There were ample nails for the crucifixion of the

neurotic.

The buses loomed tall past the weed-high windows. Early morning top-deckers

regularly observed the stirring habits of the lesser Prefabricators - the queer

birds who were reputed to be related to the human species. More like rabbits

with their hutch accommodation and breeding habits.

In prefab number 10, Joe lay in bed with the bedclothes over his head. His

neurosis hurt. The dingy, box-like room offended his eyes with its squalor.

Everything visual around him emphasized his inability to come to terms with

economics. He couldn't work, or wouldn't work, or both. He could hear his wife

creaking about the kitchen, scraping together some kind of breakfast for him. He

could see the wanting numbness in her face, and closed his eyes under the

protective bed-clothes, to shut out the sight. The dry membranes of his

compassion rubbed together and hurt.

Reluctant to relinquish the womb-warmth of the bed-clothes, Joe reached out to

the bedside chair and captured the remains of a twice extinguished Woodbine.

Lighting the sparse, sorry-looking dog-end, with his head on one side to avoid

igniting his nostril hairs, he inhaled with the desperate luxury of poverty.

After a few courage-building puffs, he descended from the lifeboat of his bed

and pulled on his clothing. He had work to do.

Through some miracle of tenacity Joe still retained the residue of creative

desire. His untutored response to Degas and Rachmaninoff was unbelievably

touching. His knowledge of Wedgewood and Chippendale a profound paradox in his

bare, matchboard environment.

He loved the bold warmth and brilliance of the Impressionists. His grey life

responded to their sparkling message of light and colour. He had decided to

paint a Monet sunset. On an old canvas that he had acquired for a wheedling

sixpence, depicting a landscape with mathematically defiant perspective, he had

applied a layer of white undercoat.

He sat on the edge of the bed, with the canvas on the floor, and laid out his

pauper's palette of student oils and methylated spirit. With two lonely brushes,

and a biscuit-tin lid on which to mix his colours, he began to paint. The Monet

reproduction, on an old calendar, was all reds and oranges and evening shadows.

Joe copied it with great ease in two hours, hung it on a picture hook, packed up

his basic painting kit, and went back to bed. In the gilt frame that had

contained the original picture the cockney Monet glowed with authenticity. Joe

hung it, with mild satisfaction, on the bare yellow wall of the living room. Its

evening embers shone like a dying fire against the ochre background.

His wife, who was blind in one eye and had poor vision in the other, thought

that it was nice. His two youngest sons, who remained resident in the prefab,

agreed that he was a clever old sod. The picture graced the wall in solitary

splendour until the insurance agent, who called doggedly but without hope for

the accumulating arrears, chanced to catch sight of it through the open front

room window. He became excited over what he thought to be a genuine original oil

painting in an elaborate old gilt frame.

His relationship with the family was long-suffering, but sympathetic. There was

no great joy in his job. The pleasure of dispensing endowments was too often

counteracted by the grief of accompanying death.

The collection of premiums often aroused feelings of guilt when the money could

obviously be ill-spared. Never-the-less he had his own problems, and his sketchy

knowledge of painting told him that he might be looking at a fortune in oils.

Although he normally never entered the house he asked if he could come in and

see Joe. Thinking that he might get a fag out of it, Joe reluctantly allowed him

entrance. Accepting a cup of tea in the best cup, the agent sat down and offered

his cigarettes, Joe inhaled hungrily and waited for the catch.

"You might be able to do me a favour," the insurance man began casually. "I've

just decorated my front room, and I'm looking for a picture to hang over the

fireplace." He pointed to the pseudo Monet that radiated from the wall. "I

wondered whether you would sell me that one."

Joe looked at him in pity. An oil painting over the fireplace? He deserved to be

fiddled. Without any haggling the agent paid £2 and squared the insurance

arrears. He left with the treasure clutched excitedly under his arm. With the

proceeds, Joe treated himself to a bottle of cheap Spanish wine and ten

Woodbines. His wife spent the remainder of the money on much-needed groceries.

Opening the bottle, Joe retired to the bedroom. Lying on the bed he swigged and

puffed away in moderate contentment. How many pints of oblivion, he reflected,

would a real Monet buy?

He thought with regret of the wasted years of his life. The constant pain of

fear. His only gauge of happiness; degrees of suffering. That which hurt the

least was happiness. That which didn't hurt at all, ecstasy. There wasn't much

that didn't hurt.

The bellow of a radio from a neighbouring prefab twisted in his wounds. He

covered his ears with his hands.

When the insurance man called again, he asked to see Joe, who confronted him

with some feeling of apprehension and guilt.

"What do you want?" He asked guardedly.

"I just wondered where you got the picture," said the agent, very amiably.

Joe was very suspicious, and wondered what the penalty was for selling a forged

Monet.

"Why do you want to know?" he queried belligerently.

"I'm just curious," said the agent. "It was so well done."

"If you really want to know," said Joe, with a touch of pride and defiance, "I

painted it myself."

The insurance man looked at him incredulously. "Did you really?" he said,

admiringly. He thought for a moment and coming to a decision, said, "Will you

paint me another half-dozen?"

Joe's bent back straightened perceptibly and his face creased with artistic

indignation. "What do you think this is, a bleeding factory?" he replied, and

with a disdain worthy of the great Monet himself, withdrew to his bedroom

studio.

J.B. Taylor

SIGNING ON

Lining up behind the backs of unseen faces

In front of unknown ones,

Ready to sign the paper with a flourish

And resign myself to the facts,

Not wanted here or there.

The unknown hold time still

Like a Judge at court,

Wanting work and found wanting.

Waiting in line for the recompense.

Give us our daily giro.

The rumour of work scares the veterans,

The young grab with one hand in their pocket

Anxious to be rid of the smell of no work.

Today is here and tomorrow never comes,

Leaving us still waiting for the war to come.

Steve Townsend

MAD MAN SAM

Sammy was a maniac Mad Man Sam they called him. He was easy the biggest in

Eddie's gang. He was over six feet tall but he had tight curly hair, like a

negro's only bright red, and it stuck up so much that you couldn't tell where

his head ended and the hair started, and lots of fellers said that if Mad Man

Sam's hair was shaved off, he wouldn't be over six feet tall anymore, but that

didn't bother Mad Man Sam, 'cos he just asked them when they were thinking of

trying it.

Mad Man Sam's mother was dead. She was an Irish woman so she had a good voice.

She died in Pat Moran's pub one night when she split her windpipe open on a

peanut, just as she was starting to sing "I'll walk you home again, Kathleen".

Everyone said it was a shame, it was such a lovely song. She was short, round

and fat and looked like a turnip, everyone said, but I think the people who said

that were only trying to be smart arses, 'cos everyone knew that Sam's father

was a Swede off a boat that stopped over in Liverpool one night. A lot of people

made jokes about a turnip, a swede and fuckin' big carrot. Behind Mad Man Sam's

back they made them. Still, it was funny to think of Sam as a fuckin' big carrot

and his main as a turnip, 'cos you saw them together a lot when she was alive -

like when Sam would carry her shopping bags and there she'd be, waddling along,

her two hands just meeting around the front of her belly, clutching this little

hand-bag, and next to her would lollop Sam, his carroty head on his big broad

shoulders and his arms dangling down so much that the shopping bags made tracks

up the street. Yeah, it was funny to think that way when she was alive.

'Round about the time that Mad Man Sam's mother died, and Mad Man Sam's

shoulders got bigger and bigger, and everyone stopped calling him Carrot Top,

and started calling him Sam to his face and Mad Man Sam behind his back - 'round

about this time, all the big lads started to wear winkle-pickers. But Mad Man

Sam shouldn't ever have worn winkle-pickers 'cos he had the widest feet you ever

saw and the only winkle-pickers he could get into were size twelves, and he took

a size nine really. When Mad Man Sam wore his size twelve winkle-pickers, you

could see a deep crease in each shoe just where the laces started and that was

where his real toes ended inside, the rest of the shoes were hollow - y'know,

the real pointy bits were hollow - and turned right up towards the sky. Someone

once said that Sam looked like a giant pixie in his size twelve winkle-pickers.

He fell over a lot when he wore them.

Mad Man Sam used to say that his feet were so wide he could walk on water. One

day someone else said that they weren't as wide as Mad Man Sam's mouth and Mad

Man Sam ought to put his money where that was. Mad Man sam replied that he

thought his knuckles were bigger than the mouth of the feller who'd just said

that but any minute now he was gonna make sure. That was pretty quick for Mad

Man Sam, so I reckon he'd heard it before. Then there was an argument. Our Eddie

ended it by saying how a bet was a bet and everybody went up the canal.

On the way to the canal, Mad Man Sam called in at his uncle's. Mad Man Sam had

been living there ever since his main had died. His uncle was five feet two

inches tall and he said he didn't really mind having Sam around. His uncle liked

breathing, everyone else said. When we got to the canal, Mad Man Sam took out

some water wings and blew them up and lashed them to his feet. Someone said that

that wasn't fair, but our Eddie said he was only talking through his pocket;

water wings were o.k.

Mad Man Sam took off his jacket and rolled up his sleeves and he looked funny

with his bony elbows sticking out like brush-poles and his arse sticking out

like he'd shit himself, as he stomped to the edge of the canal. Eddie and Tommy

took one each of his arms and there was another little argument about how long

Mad Man Sam had to do it for. Ten seconds they said in the end. Then they

started to help Mad Man Sam test the water. It was as if they were lining

someone up to be shot, it was so slow and exciting - with Mad Man Sam chattering

about they shouldn't count too slow and the feller he'd had the bet with

clapping his hands about once every three seconds, to show how long a second

was.

The water was only inches down from the bank, and you could see rainbows on the

oily surface. Mad Man Sam stuck his left foot into the canal. It went under by a

few inches and then started scouting away from him as he put some weight on it.

He lost his balance a bit and started waving his arms around but Eddie and Tommy

got a grip of him and Mad Man Sam dragged his foot out of the water back onto

the bank, and the dirty oily water poured out of his half hollow winkle-pickers.

On the surface of the canal, where his foot had been, you could see a break in

the oily scum but it all sort of filmed over again a few seconds later. We all

started booing and slow-handclapping him for not going all in, and Mad Man Sam

was getting mad. Next time he put his right foot in and it went under and away

from him again as he put his weight on it. He dragged it back towards the bank.

We were clapping a bit faster now. The feller Sam had had the bet with was

shoutin that Sam shouldn't think we were clapping once every second, we were

clapping much faster than that. Some were still booing too and some were

laughing. Sam put his weight on tile foot again and again it shot away from him

but the laughing and clapping and booing must've got to be too much for him 'cos

this time when he dragged his right foot back he brought his left in as well. We

all stopped clapping and we all shut up and just for a split second Mad Man Sam

stood on the water, sinking a little bit, and then he whooshed over longways

away from the bank in a kind of semi-circle so that his head went in about seven

feet away from the bank and his short striped socks, winkle pickers and water

wings bobbed up about a foot away from the bank.

Everyone started roaring. The feller Mad Man Sam had had the bet with started to

jump up and down. Where Mad Man Sam had gone in, the water was clear, and, even

though the scum was trying its best to knit together again, it couldn't 'cos Sam

was upside down in the water and thrashing about and making little waves all

around him.

I was watching Mad Man Sam in the water. His arms were going fifty to the dozen

and he was trying to bend himself upwards to get to the shoes and the water

wings. His hair didn't look red down there, more orangey, and it was funny how

slow it moved - curling and nearly straightening and curling again, really,

really slow when every other bit of Sam was going like the clappers. After about

a minute, bubbles started to come from Mad Man Sam's mouth and his eyes were

getting poppier and poppier and I could tell he was terrified. The others were

still laughing and wise-cracking and it was then I thought of the story of that

girl in New York - Kitty something her name was. She was murdered in the middle

of the afternoon in some room off a main street with thousands of people walking

past the room and hearing her screams. and not one of them going in to see what

the score was. And now, here was Mad Man Sam drowning in the canal with all his

mates laughing just a bit too loud and looking everywhere and anywhere except at

Sam. And then I knew why nobody helped that Kitty, 'cos I knew why nobody was

going to help Mad Man Sam.

I told Eddie that Mad Man Sam was going to drown if he didn't get him out quick

and I cried when I said it, so that Eddie could wait for a bit and decide to get

Sam out for my sake. "Su as not to upset the kid', he said. Everyone looked

better when Eddie said that and they all rushed to pull off Mad Man Sam's

squelchy shoes and water-wings. Sam came up coughing and sobbing about six feet

away from the bank and lunged toward the bank, still coughing up water, for the

others to pull him out. Sam didn't jerk anyone in as he was getting pulled out,

so I knew he was in a bad way. He flopped down on the bank with a kind of splat

and lay there on his belly, heaving and coughing and cursing as Eddie's mates

said, loud enough for Sam to hear, that they should've got him out sooner, that

it was dead brave of Sam to have tried it. that he was on top of the water for

about a second, that no, he was on top of the water for just on two seconds, and

the feller he'd had the bet with said that it didn't matter about the money

anyway. When the feller Sam had had the bet with said that it didn't matter

about the money anyway, everyone turned on him and said too true it didn't

matter about the money and Mad Man Sam was going to give him a good hiding

anyway no matter how much he tried to suck up to him and, what was more, if Mad

Man Sam was brain damaged, and couldn't give him a good hiding, they would, on

Mad Man Sam's account 'cos Mad Man Sam was a mate of theirs, and that's what

mates were for. Mad Man Sam just beat his fist on the ground and coughed.

For two or three days after that, the reddest thing about Mad Man Sam were his

eyes. The feller Mad Man Sam had had the bet with got off the hook 'cos Sam

claimed the bet and was paid 'cos everyone agreed that walking upside down in

the water for over a minute was miles better than walking on top, the right way

up, for ten lousy seconds.

Jimmy McGovern

CANADIAN WORKER WRITERS. "Quitting Time" is by Mark Warrior taken from a book by

the same title. The other three poems are from "'A Government Job At Last"

edited by Tom Wayman. Both books can be ordered from the Federation of Worker

Writers and Community Publishers, F Floor, Milburn House, Dean Street, Newcastle

upon Tyne, NF1 1LF.

QUITTING TIME

we fall silent, watching

the smoke belch from the tower,

the rain stream

down the windows of the crummy.

the hooker butts his cigarette

and throws the door open.

"guess it's that fucking time again."

four hours till lunchbreak

as i climb over the pile i think

how after lunch i'll be waiting

out the four hours till quitting time,

at quitting time, waiting for sunday,

on sunday, for fire season or a strike,

after fire season, for the winter layoff.

at night i dream

of a vast, green

waiting room

which is slowly filling with rain.

and as i drown

am angrily shouting

that i've been cheated, robbed

of the right to watch

my life pass before my eyes,

this life spent waiting

for the slack-off whistle to blow.

six down, forty years

to go: the rigging stops

and as i kneel beside

the windfall we left yesterday,

groping for the knob, cursing

this first turn which already

has me covered in mud to the elbows,

start thinking

of the warmth

of the wash-house,

of dry clothes,

of lying on my bunk

staring at the smoke

curling upwards

from my cigarette.

jesus, eight fucking hours till quitting time

Mark Warrior

NOT WANTING

TO FUCK

Not wanting to fuck a hungry woman,

I got a job.

Spent the day in a ditch with a shovel

and a little less dirt every minute.

Dragged my ass home

with a steak

and six-pack

to toast my woman.

The steak stuck to my tongue like dust.

Too tired to fuck a fed woman,

I slept. I woke at seven

and pulled myself out of bed

like a deep splinter.

The days go like this.

My hunger grows deeper with every cheque.

It rises from a hole on a shovel

and is dumped around my legs.

Rich Duquet

SOME DAY

Some day I'm gonna stand up on my desk

take all my clothes off

and hurl the typewriter at your head

And I'll squirt gestetner ink

all over your board room

with its rosewood chairs

Some day I'll shove every paper clip

into the xerox machine

and set it at a million

And then I'll throw your file cabinets

on your antique carpet

and piss on them

Some day I'm gonna force you to lick

1000 envelopes cross-legged

with nylons on dear

And I'll make you chew three dozen

shiny new pencils

and watch you die of lead poisoning

Someday I'm gonna claim compensation

for mind rot

and soul destruction

And for sure I'm never gonna write

one folksy line about the heroism

of women workers

Dierdre Gallagher

DO YOU LIKE MY

HAIR?

Do you like my hair?

I had it done today, got a new permanent.

I sat for two and a half hours with hot rollers

poking into my scalp and chemicals running down

behind my ear.

Do you like my new shoes?

I can't walk very well in them.

Do you like the book I just read?

I heard it was good, so I read it, and

I enjoyed it, but I wonder, do you like it?

Do you like me talking about books?

Do you want to go to a movie?

Do you like your coffee black?

Do you like being asked if you like your coffee

black?

Maybe it's hard to know what you like,

when you're always being asked.

Maybe I should stop asking and just try to

figure it out.

Do you like me?

Do you like the dinner, and your shirts

the way I ironed them? Do you like our kids?

Do you like the way I look when I'm pregnant?

Well, O.K. that's not a fair question, but

I don't like the way I look because I think you

don't.

Do you like women with hairy legs?

Do you like the models in the panti-hose ads?

Do you like garbagemen and supermarkets and

cleaning toilets?

Do you like women with minds full of garbagemen

and supermarkets

and cleaning toilets?

Do you like the way the floor gets dirty when

the dog runs in?

Do you like making love with me on top?

I do, but I can't come that way.

Do you believe this poem?

I bet you don't like it. I don't like it either.

I can't help it though. Do you understand?

Do you get angry about women's lib? I do.

Do you get bored easily?

Do you think you should have an affair with

every person you fall

in love with? Do you think I'm easy?

Did you think that when we met?

Honest, I want to know, did you think that?

What are you thinking about now?

Do you consider me aggressive?

Would you rather I was quiet?

But would you be bored then?

Do you find me too smart or too dumb,

too pretty or too pale,

too much like a wife or too much a whore?

We know it's your choice, we know the rules.

If I stop playing, will your ego collapse?

If your ego collapses, will my ego collapse?

Will we still be together, two collapsed egos?

Or will mine get stronger faster?

Do you like women with strong egos?

Collapsed egos?

Do you think this is funny?

Katherine Govier

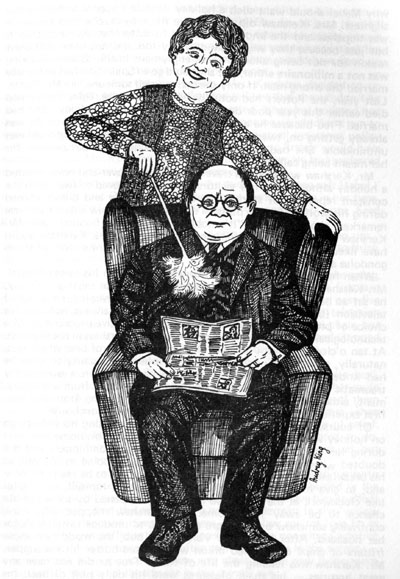

THE IDEAL HUSBAND

Mrs. Kershaw has a wonderful husband, one who never interferes, makes a fuss

or gets bad-tempered. He sits by the fire, always immaculately dressed and

well-groomed. Reading his paper or watching television seem to be his favourite

occupations and he never gives his wife any cause to complain, but it was not

always so. Far from it!

Mrs. Kershaw was a spry little woman in her sixties. Mr. Kershaw was a little

older. He was seventy and had been retired for the last five years.

"And don't I know it?" thought Mrs. Kershaw plaintively. "I wish he would get

out of the house more often."

The truth was that Mr. Kershaw got on her nerves. He was in the way. During his

working life, he had hardly been at home at all. He had been an engineer's

fitter, travelling all over the world and earning good money, most of which he

had put away for 'a rainy day'. That day was now here or so his wife thought.

They had had no terrible misfortunes and they owned their little terraced house

with its tiny garden backing on to the main railway line between Manchester and

Leeds. People usually saved up for their retirement. Well, now they were

retired. She still did a bit of cleaning at the Doctor's surgery, but she would

have liked to give it up and enjoy a well-earned rest.

She sighed as she rang out the floor-cloth in the waiting room before the first

patients were due to arrive. The 'fly in the ointment' as they say, was that Mr.

Kershaw was so tight-fisted. Saving had become a way of life for him and without

her small wage, Mrs. Kershaw knew she would not have been able to treat herself

to a weekly shampoo and set at the local hair dresser's or buy more clothes than

were absolutely necessary to be decently covered. She had something to ask him

now but as it involved spending money, she had little hope of a favourable

outcome.

It was raining in fact and not just proverbially when she stepped out into the

street and made her way home. It was not far and she was soon walking up the

gravel path which led to the back door of the house. The front door was hardly

ever used. The garden was neat and trim. The dahlias, the pride of Mr. Kershaw's

heart, held up their many-petalled heads to the rain. Mr. Kershaw might have

been in the garden had it been fine. Now he would be in her way again and she

would have to dust and vacuum round him while he read his paper, oblivious of

her efforts, but grumbling heartily if she suggested he might move out of the

way.

Her step quickened. It was almost nine o'clock and time for her husband's

breakfast which was placed before him regularly at nine each morning.

"Is that you, Mabel?" she heard him call as she entered the house. She poked her

head round the living room door as she stood in the kitchen, having divested

herself of her wet raincoat and put her umbrella in the sink.

"Yes love," she said. "I'm just going to get you your breakfast."

The boiled egg (one rasher of bacon and a fried egg were luxuries reserved for

Sunday) was soon ready. It was just right. Mr. Kershaw ate alone, his wife

having breakfasted much earlier before going out to work. Mr. Kershaw liked his

egg to be boiling for three and a half minutes exactly and on the rare occasions

when Mrs. Kershaw erred in this respect, he ate the offending article (you can't

waste a good egg) but in sulky silence. Mrs. Kershaw didn't mind this too much.

It was her husband's obsession with petty economies which increasingly irritated

her.

When he had finished his breakfast, he went back to his arm-chair by the fire

where he sat, without a tie, in his shabby suit and frayed carpet slippers,

reading the paper. The open fire looked very pleasant certainly, but his wife

would have preferred one of those modern gas fires which would have meant less

work for her. It was she who fetched in the coal and cleaned the grate. Even

now, in August, there was a small fire burning.

Mrs. Kershaw cleared the table and got out the vacuum cleaner. The badly worn

carpet had covered the floor for the past thirty years. Its original oriental

design of predominately red and yellow hues had faded into a uniform dirty brown

shade and the rag rug which had been in front of the fire place was now placed

strategically in the middle of the room to conceal a large hole. Mrs. Kershaw

would have died rather than allow anyone to see that hole. The possibility of

such a thing happening haunted her dreams. She had never liked the heavy

mahogany sideboard either, with its large ornate mirror. It dominated the tiny

room, enlarging it certainly by reflecting it in its entirety, but she resented

this duplication of its shabbiness which seemed yet another affront to her

housewifely pride. The sideboard had been bought years ago at a sale because it

was 'a BARGAIN' She covered the innumerable scratches, inflicted by her son's

penknife in his childhood, with a liquid polish designed for that purpose, but

her dislike of its gloomy bulk was rapidly turning into hatred. The old deal

table was shabby too and none of the chairs around it matched each other. She

would have loved to possess a modern dining room suite with matching table,

chairs and sideboard, but Mr. Kershaw said what did it matter, they weren't

living in Mayfair.

There was a large framed photograph of Peter, their son, on the sideboard, and a

smaller photograph of a family group tucked in the right hand corner of the

frame. Behind it were stacked the letters he had sent from Canada. They were

addressed as was only right to both his parents, but it was Mrs. Kershaw who

always wrote back and who awaited eagerly the arrival of the postman. Peter had

emigrated to Canada several years ago now. She had never seen his wife or her

grandchildren except on the little photograph. It was Mrs. Kershaw's dream to

visit them one day, but Mr. Kershaw said how could they? They were not

millionaires!

They had only the one son. No other children had arrived. Although she liked

children, Mrs. Kershaw had long since realised her good fortune in this respect.

She had seen neighbours, making themselves ill with worry, worn out with large

families and sometimes even risking back street abortions. Now people had

smaller families and many husbands helped with the housework when their wives

went out to work, but it was hard to keep up with some of the new-fangled

notions. Mr. Kershaw thought they were all crazy.

"Women aren't the same as men," he would say. "All this talk about being equal

just breeds discontent."

He would have been surprised to know just how discontented his wife was,

although she made the best of her situation. He was not a cruel man, just one

lacking in imagination or sensitivity. Call it what you will. The world abounds

with the likes of Mr. Kershaw.

Now, as she dusted the sideboard, Mrs. Kershaw was inwardly summoning up all her

courage to ask Mr. Kershaw's gracious permission to go on a package tour to

Spain with her widowed friend and neighbour, Gladys Buckley. It was one at

reduced rates for pensioners. They would be setting off in a month's time and

Gladys said that there were still a few spare places left.

"Fred," she said. She had finished the sideboard and was dusting the clock on

the mantelpiece.

Mr. Kershaw did not look up. It was difficult to attract his attention when he

was absorbed in the gardening page of the newspaper. She repeated his name a

little louder.

"Fred, Gladys is going to Spain and she's asked me if I'd like to go. I've saved

up a bit myself, but I should need a bit more. I'd be away for two weeks. You

could come too, but I don't suppose you'd want to.

Her husband looked at her in amazement. "What do you want to go there for?" he

asked cantankerously. "Everyone will be crowded on the beaches with no room to

move between the deck chairs. They just think they're enjoying themselves." Then

came the inevitable. "Besides we're not millionaires."

He re-immersed himself in the newspaper. He genuinely did not see why Mabel

should want such a holiday. It didn't appeal to him in the slightest. Mrs.

Kershaw did not pursue the subject. She had known it was hopeless and the

knowledge served to soften her disappointment, but just because they were only

ordinary folk did not seem sufficient reason for not being allowed some

enjoyment in life. Gladys Buckley was not a millionaire either, but she could go

to Spain. She had definitely married the wrong man. If only she had married

someone like Mr. Potter. Last year, the Potters had actually been on a cruise.

(Mrs. Potter had died earlier this year poor dear, but she had had her holiday.)

She had married Fred because he was the only one who asked her when she was

already getting on, twenty-five to be exact, and to be an old maid was

unthinkable. She had never stopped to consider why but prestige for her meant

being called "Mrs.".

Mr. Kershaw was glad his travelling days were over and never wanted a holiday

although the few visitors they had he bored to tears with the constant

repetition of stories about events, people and places abroad during his work in

foreign parts. A mate of his, a fellow fitter, had once remarked about Venice:

"It's nobbut like a town flooded' and Mr. Kershaw seemed to be of the same

opinion, but Mrs. Kershaw would have liked to have seen Venice. It must be so

romantic with all those gondolas and gondoliers.

When he wasn't getting on someone's nerves with his tales of travel, Mr. Kershaw

pottered a little in his garden but for most of the day, he sat as he did now,

reading by the fire. In the evening, he watched television (black and white of

course) and they always watched his choice of programme. He liked sport and

informative programmes of a technological nature which did not interest Mrs.

Kershaw in the slightest. At ten o'clock, he went down to the local for a pint

of beer which was, naturally, exorbitantly priced and vastly inferior in quality

to what he had known before the war. The thirties had not been a particularly

traumatic time for Mr. Kershaw. He had never suffered from unemployment,

although his obsession with thrift surely sprang from the fear, first

experienced in his youth, of pauperism and the workhouse.

Of course, one reason, money apart, for not wanting his wife to go on holiday

was that Mr. Kershaw would have missed his home comforts during her absence. He

had never had to fend for himself and she doubted whether he would have been

capable of doing so. As well as his breakfast, he always expected his dinner and

tea to be ready on time and, to give him his due, he was always punctual,

himself, turning up like clockwork at the appointed hour if he happened by some

remote chance to be away from home. Mrs. Kershaw shopped with care, contriving

somehow on a meagre allowance to produce tasty meals for her husband. After his

nightly visit to the pub, she made him apple fritters or chips or a boiled onion

with melted butter for his supper. Mr. Kershaw was leading the life of Riley.

True he did not have any great luxuries - his main pleasures were his daily pint

of beer, his weekly four ounces of tobacco and tending the dahlias in his garden

-but then he didn't want any. Mrs. Kershaw did. She would have liked to go

abroad or go on a cruise, to have a colour television, a new carpet and some new

furniture. What was so aggravating was to know that the money was there. Had

they been really poor, there would have been no alternative but to live in this

cheese-paring manner.

Her chores over for the time being, Mrs. Kershaw decided to go across the road

to see Gladys Buckley and tell her that she wouldn't be able to go to Spain. Her

friend was exasperated. When her husband had been alive, they had spent all

their modest income which didn't run to trips abroad, but Mr. Buckley had taken

out a small insurance policy and now his wife was enjoying the proceeds as poor

Arthur would have wanted her to. Mr. Kershaw had no insurance policy. He had

preferred to save his own money pound by hard-earned pound.

"You should nag until he gives in," she said. "You're too soft Mabel." Rumour

had it that Gladys Buckley had done some nagging in her time, but Arthur Buckley

had had a different temperament from Fred Kershaw.

"You don't know Fred," said Mrs. Kershaw. 'It would be no use.' The two friends

had a cup of tea together and then it was time to think about preparing dinner.

That afternoon, Mrs. Kershaw went into town to do some shopping. When she

arrived home, it had stopped raining so she was at first surprised not to see

Mr. Kershaw in the garden, but as it was past five o'clock, she said to herself

that he was probably watching television before his tea at six. Sure enough,

there he was in the old arm chair, but the television was not on. He seemed to

be asleep. His head had slumped sideways. She touched his shoulder. He did not

stir.

"Fred," she said gently and then a little louder, "Fred!"

There was no response. She drew back in alarm. He was quite dead, but still

warm. He must have died in his sleep just now. It gave her quite a turn to think

about it. He had not been ill. Indeed neither of them had seen the doctor for

years. It was sad, but to be quite honest, when the first shock had subsided,

what she really felt was a sense of relief. Now she would be able to do all the

things she had wanted to do. Perhaps it wouldn't look quite decent if she went

to Spain just yet, but she might even to to Canada eventually.

Ah, but he did look peaceful, sitting there. It seemed such a pity to disturb

him. She could not bear to think of him being buried in the cold ground or

cremated in a hot fire. No, she would have him stuffed! She could surely find

the address of a good taxidermist in the 'yellow pages' of the telephone

directory. There was no law against it as far as she knew. He was sufficiently

well-preserved not 'to constitute a public health hazard' - a phrase she had

often seen on notices in the surgery -and he'd look ever so nice in a new arm

chair on the new living-room carpet which she could already see in her mind's

eye.

The neighbours were thunderstruck at first, but now they are quite used to

seeing Mr. Kershaw, looking perfectly contented, sitting permanently by the new

gas fire, in the smart blue arm chair, standing on the bright new carpet with

its busy pattern of blues and greens, on which stands also the smart new dining

suite of highly polished walnut veneer.

The ideal husband, at last, he seems to Mrs. Kershaw to put the finishing touch

to her surroundings and, as she is sometimes heard to observe, "It's nice to

have a man about the house!"

Ruth Allinson

BETTY

a square woman with diamond arms

on big fleshy hips

red hair red face

red roaring curses from

the slash she snarled with

at the staggered kids

tied up in a pinny

the great splitting belly laugh

would jiggle her fat breasts

throwing the broad face

into sudden violent disorder

at something that amused her

Vivien Leslie

NUPE recently ran a poetry competition in their union

journal which revealed quite a range of talents. Here we

publish a sample of their entries.

J. E. Adkin is a Caretaker at Portsmouth Polytechnic

LONG DISTANCE

Have I got a Daddy?

I often ask myself

And who's that in the picture?

Mum keeps upon the shelf

Not a picture of an airman

Or a deep sea diver

Oh! Mummy is my Daddy dead?

"No love he's a Driver".

J E Adkin

WAITING

What are those people doing?

They are waiting.

What are they waiting for? a film show?

No.

Christmas?

No.

The number seven bus?

No.

They are waiting to get on the Public Tennis Courts.

That can take a long long time.

One of them is very angry.

He will write a complaint to the Town Hall.

Or maybe the County Council.

No, he has decided to go straight to the top.

He is going to send a letter directly to Mr. Wilson.

Hmm, he's been waiting longer than I thought.

B. Lyons

BRITISH PRAYER

Our Mother which art in Downing Street

Margaret be thy name;

United Kingdom going,

We shall be done on earth and probably in Heaven;

Give us each our daily cuts

and forgive us our misguided confidence,

As we forgive them that speculate against us.

Lead us into a General Election

and deliver us from the folly of our ways

For this is the Kingdom - Power to those who have

and the survival of the fittest.

For ever and ever Amen.

NUPE Aberdeen No 1 Branch

SAVE OUR

SCHOOL MEALS BATTLE CRY

At National School Meals Conference

We heard a lot of common sense

The ladies came from far and wide

A course of action to decide

If meals at schools are to exist

The drastic cuts we must resist

So raise the NUPE banner high

Don't let our school meals service die

But rally round and heed the call

For school meals cuts affect us all

To fight the cause of malnutrition

Keep up the standards of nutrition

Some families are poor and need

The school meals dinner for a feed

And working mothers in the land

Are glad of school meals helping hand

So raise the NUPE banner high etc.

The school meals part of education

Will help to build a healthy nation

So ladies now we call to you

Don't leave the fighting to the few

If we are going to save school meals

Don't just sit back and cool your heels

But raise the NUPE banner high

Don't let our school meals service die

We'll rally round and heed the call

For school meals cuts affect us all

Doris Jennings

HOSPITAL KITCHEN

Morning Muriel, How are you feeling

Start the motor these spuds need peeling

Tank's overflowing looks like a choke

Grab a stick and give it a poke

Wash down the yard, clean out the drains

No need to do this if we only had brains

We are only antiques according to Smash

And those little tin men so bold and brash

Look at the peelings all over my feet

Can't stop to clean them here comes the meat

Stack in the cold room, oh! it's freezing

Now then "Albert" stop that teasing

I'll do the salads, you wash the greens

Then we'll start on those tins of beans

Must drain the sinks, you take the tea

I'll slice the beans while I'm having a pee

Tote that cabbage, lift that kale

Oh! how I wish that I was male

Dear oh dear my legs are sopping

Need the bonus for my Xmas shopping.

Bet and Muriel

SWEET CHERRY

Moonlit trees, pale shadows creeping across wide green

lawns

Quiet now little foxes, patiently waiting watching in

hiding, the quick furry rabbits,

Large badgers, padding around the out-buildings

looking in bins, delighting the patients!!

Small animals too, their white-striped, mask-like faces

Youngest of badgers, silently watching

Startling the night-nurse as she closes the curtains.

Mrs A Lowrie

ASPECTS OF LUNACY

on nights

to the sounds of sleeping children

I would my eyes would not succumb to dream

and make of this my light time

and reason watch me through this watching

but the full moon at my window

like a silver breast hanging on the torso of the night

seduces me to wild imaginings

in company of stars

in hopeless flying fancy

all His fair creation I would have my plaything

and I am crushed

before the magnitude of my task

to order such infinity

later

kneeling at the side of the fitting child

as, the storm abating

recognition dawns

and peace restores her features to a smile

of one who has travelled, who returns

a light on this sad mask

to equal all that star shine

I rejoice to see

such fair infinity

taken in two hands

at breakfast

over tea and toast and marmalade

I study the aquarium

its refracted imagery

the little plastic diver lies beside the spanish galleon

strangled by his air line

drowned by the weight of his own boots

while angel fish nose the cask of gold

indifferently

Time comes away in handfuls

how many hands have you

how much may be salvaged

by morning.

ERIC JONES

WHAT DO YOU THINK?

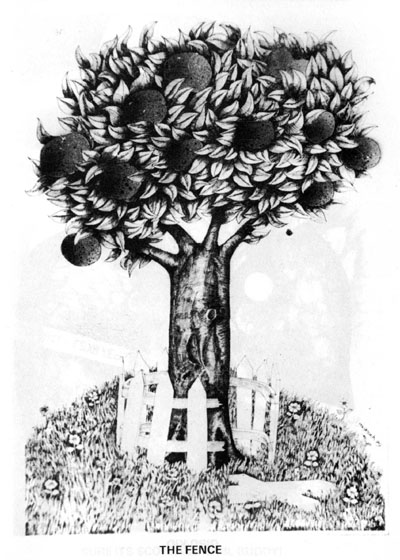

Two monkeys sat in a coconut tree

Discussing things as they are said to be

Said one to the other, now listen you

There's a certain rumour that can't be true

That man descended from our noble race

The very idea, it's a dire disgrace

No monkey ever deserted his wife

Starved her baby, and ruined her life

And you've never known a mother monk

To leave her baby with others, to bunk

Or pass them on one to another

Till they hardly know who is their mother

And another thing you will never see

A monk build a fence round a coconut tree

And let the coconuts go to waste

Forbidding all monkeys to even taste

Why! if I put a fence around this tree

Starvation would force you to steal from me

There's another thing a monk won't do

Go out at night and get in a stew

Or use a gun, or club, or knife

To take some other monkey's life

Yes! man descended the ornery cuss

But no emphatically not from us

Now you know why the monkey has such a sad face

He is sad, for the bad in the human race

But take heart, for the monkey who lives in the wood

Spoke only of bad, not seeing the good

For good there is, tho' at times hard to find

It shows here and there in the old daily grind

So carry on living and doing your best

Do what you can, for life is a test

And if you can pass it, and end with a grin

You might come back as a monkey and never know sin

Mr PT Adams

WE HAVE ALL MET HER

"Hello Mary, how's your Joe?

Haven't seen you since ages ago,

I've been to the butcher in High Street,

I've got a deep freezer it's such a treat,

It matches my washer, that's automatic,

We have a colour TV in the attic,

We got a new car, the colour grey,

Was there something you wanted to say?

Joe is dead! well not to worry,

I'll have to go I am in a hurry.

Mrs. Annie Parkinson

THE COSSIE

When I went tor seaside in 1934

Thar shood er seen me cossie

Thar couldn't ask fer moor

There wen't another lark it

Any weer at all

But I wus prowd ter wear it

Even though I wus quite small

It started as a jersey

An then it wer cut deawn

Then handed on till sleeves wus gone

and it were a faded sort o brown

Then me Main did make it

Into its present style

Ar didn't care how it did fit

Or who did care to smile

Ther wus allus this. Ar didn't beg

She had it sewed between the leg

And of that cossie I wus proud

As any kid could be

And as to my friends I proudly said

She made it just fer me

But only one thing nobody saw

It rubbed me flippin legs red raw.

Mrs. G. Kearns

A GROUNDSMAN’S

PLIGHT

Oh Lord the coming of the mowing season

increased concern and heavy workload

make stout our hearts, and strong our reason

and guide us on the troubled road

Deliver us from evil pests

crane flies, grubs and hornets nests

foul disease and fungus rot

damping off and dollar spot

Let not the committee thwart our days

spare us from their futile ways

help us start the mighty roller

pacify the impatient bowler

Weekends bring a muttered curse

with litter louts and even worse

bottles, bricks, and empty cans

scattered by the aggro fans

Anguish, gloom, and dark despair

the blasted worms are everywhere

divots, drought, and fairy rings

plus peculiar yellow things

Oh woe is me, alack a day

can't keep the seagull hordes at bay

moggies, dogs, and cursed hare

are digging up the cricket square

A groundsman bears a heavy strain

critics, torment, toil and pain

an epitaph could surely be

"THEY FOUND HIM HANGING FROM A TREE"

John Cummins

REASONING WHY

Reasoning why, that I rebel,

In this a life, I did not plan

For I am born

A working man.

I rebel against all kind

Who brake the workings of my mind

And let a lesser maker of idea

Guide them because of fear.

I rebel against a so called better class

Who say to me, don't be an ass,

Your people are not worth the trouble

Come with us, your wages we will double.

I rebel against my own

For a doctrine that was sown

of ignorance, and superstition

That grew to be our partition.

I rebel against the degradations

Of the people of all nations

Against poverty and distress

And apathy and idleness.

Against all these things

I must stand firm

If I would complete my life's term

Tho' sometimes I'll live in Hell

Even so, I must rebel.

Joseph Cunningham

SUMMER IN THE

FIFTIES

In them days of a summer Sundy...

motor cars –

green and black and heather-blue –

clicked cool beneath the church wall

of early morning,

reflecting gargoyle children

in convex chrome.

till are doctor, striding outa Mass, boomed.

'Hul. . .lo, there, sunshine!'

In them days of a summer Sundy .

girls cried.

'May-we-cross-your-golden-river?'

and boys huddled at the kerb,

picking bubbled pitch

between the setts,

moulding masks and men .

till this old woman screamed.

'Yous lot, gerroff the cart-road.'

In them days of a summer Sundy .

Billy Cotton

called from open doors

and through the garden

wafted smells of cabbage and hot ovens

and New Zealand lamb,

arresting time ...

till his band played:

'Some . . .body stole my gal . .

In them days of a summer Sundy . .

old men

in belts and braces and voluminous pants

limped across cropped turf,

bent and bowled,

sweated and cursed

as woods cannoned from the green ...

till they seen us, and bellered.

'Gerrartofit!'

In them days of a summer Sundy .

golden girls,

long-legged, lissom, blinding in white,

leaped and ran

after a ball,

lobbing it over the net

and into it ...

till one of 'em, turning, asked.

'Well, d'yer wanna photer or summat?'

In them days of a summer Sundy.

rowdy lads

with greased hair and vivid shirts

roped boats together

in a line and sang

shanties on the lake,

mooring at the island .

laughing when this parkie moaned:

'Bleedin' young 'ooligans!'

In them days of a summer Sundy .

families

grouped at the bandstand

by the brook,

or climbed Angel Hill for free,

and listened to the band and hecklers

in the woodsmoke on the hill .

till this feller come up and grabbed one

'Clever lad!' he said. 'Be a big 'elp to yer

dad . . . when yer grow up.'

In them days of a summer Sundy .

an aeroplane,

single-engined like a fly,

droned above the wire works,

beating the bounds

of happiness

towards a westering sun . .

till me main said:

'Yer tea's on the table, if yer wann it.'

Brendan Farrell

TO SIR ANTHONY BLUNT

Sir Anthony Blunt, you have been

a traitor by your own confession.

They gave you a start at MI5,

but you brought only shame to that honest profession.

Your conduct was most ungentlemanly

to act as a talent scout for the Russians,

even if most of the old school team

were waving their rattles and cheering the Prussians.

Sir Anthony, you've had opportunities

that I've never had, to put it simply.

They kept you on at Buckingham Palace,

while, me, I don't reckon I'd get back on Wimpey's.

But did you spare a thought when you gave in your

knighthood

for those of us out there still walking the line?

Sir Anthony, you have betrayed your class,

but, as far as I know, you've not betrayed mine.

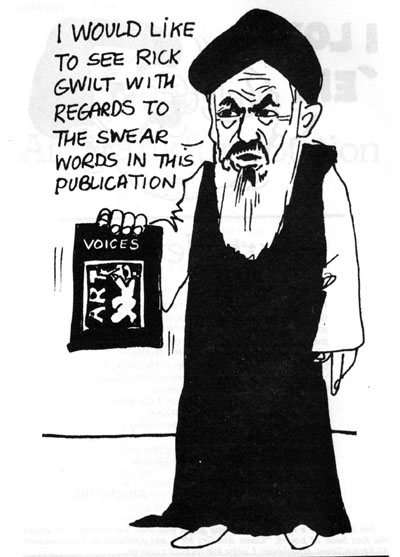

Rick Gwilt

REVIEWS

A GALLERY OF HARLEM PORTRAITS.

Melvin B. Tolson. University of Missouri Press. £4.20 Pb, £11.40 cloth.

This is a fine piece of literature. The book is a collection of poems which in

such a combination creates chiaroscuros, silhouettes, etchings and pastels.

It is by this "Art Gallery" that Tolson captures the atmosphere of Harlem, the

views and attitudes and its inhabitants. The unique description of the

characters and their environment gives the work an extra dimension. It is raised

above the level of bland black on white, the people are real and the smell of

Harlem is ingrained on the pages. The smell of squalor, poverty, marijuana, the

smell of the nice rich people and their nice houses, the smell of the small

sweet shops in Harlem.

Tolson journeys through restaurants, newspaper offices, grocer shops, lovers

bedrooms, dimly lit tenement blocks, grimy lodging houses, the W.A.S.P. south,

sleazy speak easies, jazz and blues clubs of various reputation, distracting

churches, wartime France and West Coast of Afrika to find a vivid and true

picture of Harlem and her people.

An understanding of life is brought out in many of the poems. For example, the

black understands his role and the financial rewards he can gain by playing the

role well. The negro understands the thin cover of race pride, he sees it as a

facade. This has further emphasised the view that the big fish eat the small

fish and colour is irrelevant. A dying black compels white and black workers to

unite and explains that segregation is a tool of the rich and powerful. It is

also understood that black cops may make a black feel proud but they beat you

just the same as white cops. Then there is the father who is annoyed at his son

because his son hit a white lawyer in front of a white judge and jury down in

Alabama.

Tolson spells out in a number of poems and in varying ways the rank/colour

syndrome. Basically higher rank is occasioned to one whose colour is lighter. A

throwback is that the darker people enviously look at lighter skinned blacks.

Several of the poems look at the same aspect of black history in the U.S A.

Taken together, a composite picture of black history evolves, taking it from the

time of slavery, past Nat Turner, past the Civil War and Reconstruction. Lincoln

is remembered and revered, Sherman is remembered too, the Klu Klux Klan are

remembered as are the lynchings, murders and whippings.

A finer point of criticism is that black history is only passingly remembered.

However, I received the book well and spent many days reading it to myself and

aloud to my friends who experienced the interest and amusement while hearing

some of the poetry.

Bolaji Labinjoh

SHELLEY'S SOCIALISM: Edward Aveling and

Eleanor Marx Aveling and POPULAR SONGS, wholly political and destined to awaken

and direct the imagination of the reformers: Percy Bysshe Shelley. The

Journeyman Chaphook Series 3. The Journeyman Press. £1.50.

There were only twenty five copies of the original edition of Shelley's

Socialism a lecture that Aveling and Eleanor Marx gave to the Shelley Society in

1888. Although it has been published since (by Journeyman Press as recently as

1975) this edition, which includes a selection of the best of Shelley's

revolutionary poems, is a valuable addition to any socialist library.

In the introduction to the lecture that Frank Allaun first wrote for Leslie

Prager's edition in 1947, he quotes Marx as assessing Shelley as essentially a

revolutionist" and grieving that he died at twenty-nine because "he would always

have been one of the advanced guard of socialism". This opinion is confirmed by

the analysis of Shelley's work in the lecture.

It is probable that the ideas in the lecture owed more to Eleanor Marx than the

scientist, Aveling. She was involved in discussion of literary values many times

in the Marx household.

The lecture contains a note or two on Shelley and his personality as it bears on

his relations to socialism. It analysed his thinking and those who had

influenced him in that direction and then looks at his attacks on tyranny, his

support for liberty and his clear perception of the class struggle. There are

quotations from his prose and poetry to support the contention that Shelley was

not only a convinced socialist but that he consciously set out to teach it in

his works.

The value of the lecture is that it not only gives a lead to a study of Shelley,

but also provides insight into the way of thinking and method of analysis of

Aveling and Eleanor Marx at a time when they were in touch with Frederick Engels

and many other friends of the Marx family, and it was only five years since Marx

had died.

The Popular Songs, which are prefaced by Mrs. Shelley's notes on The Mask of

Anarchy, written in the immediate aftermath of the news of the Massacre of

Peterloo, are an added bonus. They include the Ode To Liberty, The Song To The

Men of England, The Mask of Anarchy and a ballad rarely published before, which

describes a Parson who while feeding his hound with bread refused it to a poor

woman beggar whose child was dying of starvation. The sting is in the end when

he realises that the dead child was, in fact, his own.

Not only has the Journeyman Press provided a tool for modern socialists to use

in their own daily lives - a tool for personal replenishment of revolutionary

fervour, but also a tool for use in discussion and argument. Few people would

fail to be moved by such rousing words as:

"Wherefore, Bees of England, forge

Many a weapon, chain, and scourge,

That these stingless drones may spoil

The forced produce of your toil?

Sow seed, - but let no tyrant reap,

Find wealth, - let no impostor heap,

Weave robes, - let not the idle wear;

Forge arms, - in your defence to bear.

The production of the chapbook series is excellent. It looks and feels like a

privately printed press book, a connoisseur's delight, but at £1,50 it is

available to all.

Edmund and Ruth Frow

ARTHUR FRANCIS (Tonbridge, Kent) is a long-term member of the T&GWU and Labour

Party. He has served on Dover Council. This story first appeared in the T&GWU

RECORD.

NICE OCCASION, SAM

Sam Brown was going to a do. The Great Day had arrived. With the compliments of

the firm's profits he was to dine in celebration of the company's hundred years'

gain from people like old Sam.

Not that Sam understood economics. True, he was a genius on making-do on his

small wage. 'The wages of sin', he would laugh sweeping round the factory mess

that his workmates left him."

'You're not going to Buckingham Palace to be kissed on your backside', suggested

his wife, sorting out his best pair of socks.

'Steady Joan, I am going to show the stiff shirts that even a sweeper can look

tidy on occasions'.

'What an occasion!' roared the gay wife. 'A bit of turkey, or something in the

dinner hour, why, it is not even an evening affair. the old man going broke?'

'It's a big firm, Joan. It would be difficult to have a big do with guests

invited. Fair's fair.'

'Not what you said when you first heard about it.'

'Now look here me old ducks, I don't often go places. You often say I should mix

a bit. This can help'.

Sam touched his wife's shoulder as if to bless their thirty years' marriage. Her

fifty-six-year-old brown eyes smiled. His blue - a little older optics - smiled

back.

'I'll go and get the best shirt you silly old blighter. About time you showed

yourself in something decent.'

The sun was fighting to make day on that October morning. Sam watched the