|

ISSUE 20

cover size 210 x 148 mm (A5)

EDITORIAL

The TUC Working Party Report on the Arts (1976) is a curious mixture of good and

bad, of radical thinking and unquestioned assumptions. Given that, in its own

words, it was made up entirely of representatives of "those unions, twelve in

all, which have members working professionally in the Arts, education and the

mass media," it is perhaps not so surprising that at times it comes out with

statements like: "Also the job of supporting amateur activities is one for the

local authority since the Arts Council and regional Arts Associations should

only support professional artists." (p.19) But, for worker-writers struggling

with the ogres of the Arts Council, there are still a number of reasons for

believing that this particular pantomime horse has a role to play in a "happy

ending".

The report is, in an important sense, contradictory. "The working party sees the

need to popularise the Arts but does not believe that this will be achieved by

attempts to redistribute the already inadequate national resources available to

the established Arts. Only a substantial increase in national expenditure on the

Arts can lead to an increase in spending on regional, local and community based

Arts." (p.12). Understandably, the TUG does not want to be responsible for

promoting internecine struggles between street theatre and the Royal Shakespeare

Company. However, if it is all a matter of demanding more money for the Arts,

then there is the obvious danger that TUG policy on the Arts becomes reduced to

a campaign against the destructive policies of the present Government and for

the return of a Labour Government.

Now it is precisely the way in which it goes beyond such generalities which is

the most encouraging aspect of the report. If this were all it had to say, then

90% of it would be superfluous, but in fact there are some 40 pages of

interesting and specific insights.

Immediately following the passage previously quoted, the working party offers

"the view that when the Arts receive public subsidies they must do their utmost

to encourage the widest possible popular involvement in their work. No doubt

there are those in the 'Arts world' who are quite content for cultural

activities to continue as the preserve of a few. Their influence, and the

complacent attitudes which are a part and parcel of it, must be resisted."

Elsewhere (p.4) the working party has already argued that "if people are to

develop fully their mental and emotional capacities they must be able to both

appreciate a range of such activities and also be free to participate creatively

in these activities, since participation in the mastery of an artistic activity

brings insights and pleasure additional to that enjoyed by appreciation alone."

The working party has clearly seen beyond the vision of crumbs of "Culture"

being handed down from the high shelf to the waiting mouths of the uncultured

masses. Its main blind spot seems to be the assumption that "amateur" Arts are

somehow intrinsically local, while only "professional" Arts can be national in

scope. This is bound up with the uncritical acceptance of a term - "amateur"

-which is rooted in the class distinctions of a previous age, and which bears a

questionable relevance to the present-day realities of Sport and the Arts.

Worker-writers do not earn their living from writing, any more than Rugby League

players do. For upwards of forty hours a week, they are factory workers,

housewives, building workers, nurses, transport and office workers etc. But,

unlike Rugby League players, they do not tend to see their leisure-time activity

as divorced from their working lives. And this is a quality which the TUG must

value very highly, for it is a quality which will need to spread much more

widely through the trade union movement if we are to make any sense of the

demand for a reduced working week. Unless trade unionists come to place a higher

value on their leisure time - and start to fight for it - then the advent of

micro-technology is going to mean mass unemployment on an unprecedented scale

-and a working class divided down a line drawn between the factory gates and the

dole queues. This means, to my way of thinking, that any organisation, such as

the Federation of Worker Writers and Community Publishers, which is involving

large numbers of working people in this whole question of leisure, has to be

taken very seriously by the TUG as a whole.

The worker-writer movement was, of course, local in its beginnings (like most

things), but I can see no rational reason why it should be forced to remain so.

VOICES magazine, as a regular outlet for working-class creative writing, has

been national in scope for several years. Since forming a national federation

out of various local groups in 1976, the worker-writer movement has stimulated

the growth of many new workshop groups, as well as publishing last year, an

anthology called WRITING. TIME OUT said of this book: "The most striking thing

about the writing itself is its clarity, even in the poems there is none of that

wordy precociousness that normally besets the first-time writer. The literary

apparatus, all too often a source of alienation, is refreshingly demystified and

made subordinate to an overwhelming desire to document and communicate. But

perhaps the real achievement of the anthology lies in the fact that, over and

above making a reality of working-class culture, it redefines the 'political' in

terms of the struggle of individuals to recapture the right to articulate their

own situation."

Our own claims for the book were fairly modest. As Ken Worpole (Hackney Writers)

observed in his afterword; "quantity is an important forerunner of excellence:

only when working-class writing and other forms of art become relatively

commonplace activities will the production of works of great universality become

as consistent as it should, and can." However, in putting the case for writers'

workshops, Ken has implicitly put a strong case for a national co-ordinator to

extend such opportunities to many more people in many different localities:

"the workshops are vital. It is in these groups that working class people and

their 'higher-educated' partisans are coming together to read and discuss each

other's work, to fashion forms and standards which neither servilely imitate nor

petulantly reject the best of bourgeois writing. . . . The discussions, the

shared excitement in mid-wifing a stimulating piece of work, as well as the

writing itself, have helped to increase confidence and articulacy."

But if all this came as a breath of fresh air to most people, it seems to have

made little impression on the musty corridors of the Arts Council (except

perhaps to send people scurrying for shelter from the winds of change?). In

response to a request for funding of the WWCP's full-time co-ordinator (for

which the Gulbenkian Foundation has already put up half the money), the Arts

Council's Literature Panel was unanimous in its refusal, judging the Federation

"successful in a social, therapeutic sense, but not by literary standards". The

application was then shunted on to the Community Arts Panel, whose budget,

unlike that of the Literature Panel, tends to be heavily over-subscribed.

That was in March. Since then, Manchester and other Trades Councils have passed

resolutions urging "the TUC Arts Advisory Committee to form a delegation to the

Arts Council, to press them to take the worker writers' movement seriously as a

developing expression of the culture of working people, and to reconsider the

request from the Federation of Worker Writers and Community Publishers for

support for its national co-ordinator through the Literature Panel as the

single, most appropriate source of funding."

The formation of a TUC Advisory Committee on the Arts, Entertainment and Sport

has been one of the positive results of the working party report, in fact. It is

to be hoped that the TUC may yet take up the recommendation that it should

"establish an annually renewable fund for the promotion of artistic and cultural

activities throughout the Movement, and consideration should also be given to

the appointment of an arts officer to direct this work."

Meanwhile, the Federation of Worker Writers cannot continue beyond October on

its present basis. Without further funding, it must return to operating on a

shoestring. Given the background and the unrepresentative nature of the people

who make up the Arts Council (something fully recognised by the working party

report - p.17), it is perhaps not surprising that they should consider us

"nothing to do with literature". The working party report stated quite clearly

that such people must be resisted. I would suggest that the trade union movement

must begin urgently to pile on the pressure at all levels -otherwise the notion

of Tory destruction in the Arts field becomes yet another self-fulfilling

prophecy.

Rick Gwilt

July 1979.

GEORGE THE BONESETTER

I first came across George the bone setter in the late sixties, when he got a

start at the gaff where I was working at the time. Our paths didn't cross much

on the job during the first few weeks of this stay. In fact the first time I

became aware of him as a person, as opposed to just another guy on the end of

another hammer, was the morning I took my brew with a group of Apprentices whom

he had cottoned onto.

He turned out to be a very well-spoken person, with quite a lot to say for

himself. He managed to switch the brew time conversation away from the merits of

Man United to the subject to 'foul' language. His view was that swearing was the

lazy person's way of expressing theirself; he reckoned it to be the mark of a

limited vocabulary, plus a rather cheap way of drawing attention to oneself. He

went on to tell us that it particularly distressed him to hear a woman swear.

From his accent I took him as coming from a different background than the rest

of us. His views led me to believe that he was a bit of a birk.

A week or so after my first encounter with George we both got drafted into the

same bonus gang, working on a big Russian order. When we were both working on

the same pack I'd chat with him as we went along, but I never went out of my way

to get into anything more than formal conversation. Over the weeks he let me

know that he was into Leonard Cohen; wrote 'serious' poetry; knocked about with

a Nurse from Withington Hospital; studied at night with a view to getting into

Medical College, with an overall objective of learning bone setting; and went

around the pubs in Sale on a Friday night selling 'Anti-apartheid News'.

By one of those remarkable quirks of fate the Chargehand of our gang happened to

have a Daughter who had emigrated to South Africa. The Chargehand was not averse

to telling all who would listen that this country was finished in the way of

providing suitable opportunities for any young person with a bit of go in them:

'If I were twenty years younger I'd be up and away to Johannesburg. You wouldn't

see my arse for dust!' The Chargehand, Rawley, kept away from me as a rule, as

he was aware of my political persuasions which were diametrically opposed to his

on race. He also kept away from George as he had a deep embedded loathing of 'studenty

types' One night, the three of us: George, Rawley, and myself, were doing a spot

of late overtime to finish a pack that was wanted out first thing next morning.

We'd nearly got the job wrapped up for half-past eight, so we decided to make a

brew and have a sit down, thus spinning the job out until nearer ten o'clock. We

hadn't all that much in common, so it wasn't really surprising that after ten

minutes of talking about football, low wages, appalling conditions, and

inefficient management, Rawley got around to mentioning the 'beautiful house'

that his Daughter had out in South Africa. I didn't want to know anything about

it. I knew that it was a waste of time bringing any political or ethical points

up about the 'good life' out there, but I could see by the way George's eyes

were narrowing into slits that he was building himself up for an argument. With

great fortitude he contained himself until Rawley got up to telling about the

various Servants that his Daughter kept around the house, and then he let rip.

But Rawley was half ready for it. I'd already given him several doses of the

same thing in my first couple of months at the gaff, and I hadn't even dinted

his armour. He was well and truly secure behind his barricade of stock answers

that he'd reaped from the emigration brochures. He just sat back, slowly nodding

his head, and let George reel off his diatribe on Human Rights.

When George had talked himself to a near standstill, Rawley shook his head

slowly, and in exceedingly patronistic tones let George know that he had got it

all wrong. It seemed that if George were to stop looking at life through the

blinkered eyes of the Guardian editorials, and listen instead to a few

eye-witness accounts of 'ordinary' peoples' experiences of the state of affairs

in the 'land of opportunity', he might be blessed with a more balanced, and

truer, picture. As a man who had been out there visiting his Daughter for two

months, and had talked to the Blacks on equal terms, Rawley could honestly

assure George that the majority of them were happy and contented with their lot:

The new technological revolution created by the Europeans would not only provide

a better standard of living for the whites, but it would also enable the blacks

to get their share of the consumerist goodies.

I could see George getting madder and madder as Rawley went on and on like some

demented public relations officer. Finally it must have reached the point where

he could take no more. He took a deep breath, and shaped up to give Rawley what

I assumed would turn out to be the verbal thrashing of his life. But he must

have got himself wound up too tight, for when he opened his mouth nothing came

out bar a cacophony of spluttering and stuttering.

A condescending smile appeared upon Rawley's face. He must have imagined that

the force of his argument had shattered all George's erroneous preconceptions.

Then, in a flash, George lept forward across the table, grabbed Rawley by the

shirt front, and planted a right hander square on his nose. Rawley's glasses

went flying past my left ear, George let go of Rawley's shirt and stormed off

towards the clock, and Rawley slumped forward onto the table with his hands

covering his face. It happened so fast that it was all over before I realised

what was happening.

I picked up Rawley's glasses from the floor and placed them on the table at the

side of him. Rawley still had his head in his hands, drops of blood were seeping

through his fingers onto the K.J.S.U. tablecloth. Not sure what to do in the

situation, I went down to the shop floor and finished the job off.

When I clocked out at ten o'clock, I looked at George and Rawley's cards. George

had clocked out at 8.50 and Rawley had clocked out at nine o'clock.

'I thought there were three of you working over?' Old Fred the locker-up shouted

to me as I walked past the lodge on my way out through the main gate.

'Aye, there were, but the other two got fed up and left at nine,' I called back.

Fred said no more, not wishing to give the game away that he had spent the last

three hours in the bar of the Labour Club on Third Avenue.

The next day, as soon as the General Foreman got in at nine o'clock, Rawley

stormed up into his office. I had seen him watching for the office light going

on and had suspected as much.

Five minutes later the office door opened, the General Foreman stood in the

doorway and called for George to be sent up.

A further ten minutes later the office door opened again, and I was summoned to

the proceedings.

As soon as I walked into the office George blurted out:

'He hit me first, didn't

he?' The General Foreman and Rawley looked directly at me. Looking the General

Foreman straight in the eyes, I said:

'The two of them were arguing, and then

they went for each other.'

'You bloody liar!' Rawley snapped.

'Don't call me a liar, unless you want to come outside and say it,' I roared at

him in as convincing a voice as I could muster.

Rawley was about to carry on the sniping, but the General Foreman told us both

to shut up. He then asked me for a full account of what happened. I gave him the

vague drift of the incident, slipping in bits about Rawley 'coming the

neo-fascist in an attempt to provoke trouble', up to the point where the punch

came, and finished it off with them both squaring up to each other, 'I didn't

see who got the first punch in.'. The General Foreman heard my version out, and

then told me to go back to my job.

When Rawley and George came out of the office, George told me that they had both

received a bollocking, and if ever there was a repetition of the incident they

would be sacked on the spot.

Later on that morning a notice appeared next to the clock stating that in future

no overtime could be worked unless there was a Foreman on the job.

A week later George left off his own bat.

By that time Rawley had my card well and truly marked. I was down for all the

shit jobs from then on. And I couldn't leave, because Sandy was pregnant again

and we needed the money.

Michael Rowe

SMYTHE ON HISTORY

Scabs Were Here

At the dead end of the Roman lake

the scruffy tribes were battling with their god

from so long back the scribes

were numb of hand and member,

(giving their all had taken all), at the

next Union Meeting, unanimously acclaimed,

it was decided to boycott God in favour

of the Philistines, who were a decent lot

despite their eye-gouging mannerisms

and rotten Health Service. A younger scribe,

eager for reputation and a larger share

of the dumplings, leaked the Composite

to a passing Caesar playing with his galleys,

who took the biscuit and all the dumplings.

Poor Mans Legend

I remember Camelot, not for its pinnacles

like fairy tale confectionery gone riot,

nor the bed-time-tales malicious folk had told

of Arthur and his Queen, her with her come-night-eyes,

nor all that daisychain of chat about

the real Round Table for foreigners titillation.

No, ill-rumour marked me not as

monstrous masonry gave me no warmth

who lived in Goatsherd Lane among his goats

the wattle lives of crowds who could be called on

to cheer a Tourney or fill a battles casualities

for a High Lords Legend. That’s how it was

in Camelot, another feeding place for crows,

with mystic doings like a mocking tune far off.

The Woman’s Tale

It wasn't the careless eye he had with cakes,

nor the ale he supped as if we had a lakeful,

made me scold our lodger to his face

with words hard nursed from weeks of brooding;

it was the common air the man assumed

as though to meet our level at our hearth,

with spitting, grunting, farting, scratching,

jokes of fornicating monks, nunneries,

sly fondling of my nether parts, pressed

hard against me with his man 's ways as a man of mine

I knew the secret of his Kingship, t'was

no surprise to me and t'was less matter,

who would behave at palace as at home

in my own character and in no guise.

.

Breakfast With Henry

It was the capon lit him, and the goose,

cock, woodcock, quail, pheasant, snipe,

venison, beef, mutton, pork and whatnot,

all this at the same table, mind you,

delicate puddings, sympathetic soups,

monster creations of a maniac cook

to a maniac master. My married life

was mostly watching Henry eat, Henry sweet

with sugared cake, Henry marvelling

at the cooked perfection of a pigs snout,

merry at the aroma of a kitchen wench.

He had been manageable were he always eating,

I caught the in-between delirium of its absence,

the brooding hours of wanted wanting.

Printer’s Devil

Master Daniel, I know I'm only your printers devil,

and my lot in life is not to be compared with yours,

but get your poxy body out of bed

and do some work, you writing thing. Ah, Master Daniel,

awake I see, no, t'was a joke, good sir,

a talking to oneself because the hour is early,

and my master, Lord preserve him, ordered me

at point of whipping, not to return unless

returned I with at least a quire from you

of Mistress Molls last escapade. Too true,

sir, its a poxy life but life is all we've got

and mine is bound by articles to one

who would not shave because he hates to lose the hair.

So, Master Daniel, please. You'll miss the chamber-pot that

way.

Lord John

He said he was from Space, space drifter,

A kind of seed blown here from cosmic

shifts so vast none on earth or Oldham

could grasp the moments magnitude, nor him.

In earth terms I'm an Emperor Emperors

dreamed of being, less Universe than Universal,

he said: Meanwhile he kept his earthly

self in beans and butties working

as a platelayer with Twenty Nine Gang

in the borrowed body of an absent Yonner:

nowt less than total worship, so he claimed,

belongs ter me. Ah'll start wi' women,

us Space Lords are reet lads, yer know,

call me John Willie, when we're in company.

The Patton Arms

There is a pub in Warrington named after

a mad American General, luckily alive

when mad Generals were valued for their ability

to have men kill each other, so that

civilization, as we know it, might be

saved from barbarism. He must have

been important having a pub named after him,

saving civilization from barbarism. Warrington,

of course, is where the Mersey looks like slurry

on the move, the third most polluted stretch

of river in the country; a town known chiefly

for its distances from Liverpool and Manchester,

a slid-into Cheshire outlet for Main-Line trains,

a place between a Patton and nonentity.

The Guide

Some famous faces have sat upon that seat

said the man with the peaked nose,

for a small honorium, sir, there is

an amusing anecdote of a titled lady

and a sporting gentleman, well known

in country circles, sir, who attempted

that famous seat at the same time,

both being the worse for, thank you, sir,

for a further note, any colour, sir,

I could recall a royal personage,

nautical, something of a dreadnought

in his bearing, who, slipping

on a misplaced element, found his head

where the Royal arse should be!

Now, sir, if you would walk this way,

here is the bedroom where Edward The Seventh

slept alone, once, dying at the time, sir,

not many Stately Homes nor Palaces either

could boast of that!

Joe Smythe

DEAD DOG STORY

At half past one every Friday the big game starts. It's called "Catch the

Sweeper". All the lads on the brush speck their carts, shovels and brushes ready

to slope off to the alehouse. Uncle Jim Doyle, the "Walking Ganger", normally

rides round the patches checking everyone is hard at work, but not Fridays.

Fridays he is like the leader in the Tour de France, shooting from one beat to

another. He is a man possessed with stopping an ebbing tide.

To anyone ignorant in the ways of the Corpy Cleansing Department, the sight of

Uncle Jim roaring down streets, knuckles white on handle-bars, face awash in

sweat, means nothing. Woollen-hatted heads popping round corners and earnest

young men scurrying across streets fail to register in the public's mind. The

game is private and personal to us, like. We do have rules which each side

accepts; once inside the bar of Fat Anne's, snug behind a pint, waiting your

turn on the pool table, you are home or safe. Each one can tell his story or

swap with late-comers.

After hiding my cart and limbering up I made my break. From where my patch is it

should have been a dead easy getaway. Down entries, along passages I moved like

warm lard on a hot day. Just as I got to the main road, not two blocks from Fat

Anne's, I heard the squeal of brakes behind me. I knew it was him before I

turned.

"And where are you going, Clancy?", he said, as if he didn't know.

"Just going to the toilet, Jim, Why?" I could have bitten my tongue, no one says

toilet, do they? A smile the size of an overripe banana came on his lips. Then

his hand dipped in his pocket and pulled out a small white calling card.

"Have you seen anyone? Where's the Bug and Manxie? just going to join them were

you?", he said.

"I was just going to the toilet, Jim."

I'd said it again. It was the white card I was thinking about - that meant an

extra job for someone. He was getting excited. I can always tell. The nostrils

of his bulbous nose began moving like concertinas. They have a magnetic appeal

to me and my head started going up and down in rhythm with his breathing. He

soon realised what I was doing and we had one of those embarrassed silences with

his eyes burning into me.

"Before you go back to the yard, get this," he said with a snarl and handed the

card over like it was a five-pound back-hander, dead sly like. One push on the

pedals and he was gone, mumbling.

"The pride of England's youth, God help us."

He was in a good mood. I was going to put the card in my pocket and go to the

alehouse anyway, but something made me look at it. In long hand script it said:

Pick up dead dog, 24 Assisi Street, URGENT.

When I looked up he was half way down the road, his head turned back. Written

all over his face was, "I've had you." You can't win them all. I knew it would

happen sometime. So, after getting my cart I headed for Assisi Street, hoping to

God it was a mistake.

The precinct has three avenues of shops all the same size and shape that sell

mostly everything under the sun. Just as I was going through it, passing the

Betting Office, the Bug and Manxie sneaked out on me. The Bug stroking his

Zapata moustache, sidled over.

"Where are you going then, Plum Duff? No ale today?"

He gave Manxie, who had joined him, a dig in the ribs.

"Rumour has it that Uncle Jim is looking for a person to . . . er. do an

important job." Manxie said, laughing at the same time.

Then the Bug really started.

"A sort of fella that likes animals. Have you any sawdust in your blood by any

chance, Clancy, 'cause I bet you're favourite?"

He put his face on Manxie's shoulder and began to snigger. What can you say?

They know everything that happens even before the Boss. I left them holding one

another up in pleats of laughter.

24 Assisi Street was a red-bricked house with brown woodwork and a wrought iron

fence. A young piece opened the door. She was wearing no make-up, always a sign

of class, that.

"I've come for the dog," I said.

Really nice, she said,

"Would you go round the back, please?", and then walked

back into the hall.

Her little daughter was standing in the back yard. She was aged about four, with

big hazel eyes behind long lashes. Tarts in clubs spend hours trying to achieve

the same effect. A mop of black curls hung on her shoulders. She looked

vulnerable.

The dog was in a lean-to shed wrapped in an old blanket. I was getting more

nervous all the time.. Before her mother could usher the girl into the house she

asked me,

"Where are you taking my Sally, Mister?"

I know it sounds soft but I couldn't leave her without an answer.

"I 'm going to

take Sally to the cemetery. I've got a nice spot under the tree for her and I'll

give her some flowers."

The little girl burst into tears and ran into the house. Her mother followed,

after giving me an envelope. I put the shovel under the dog, Sally, and carried

her to the cart. Then my problems started. See, Sally was a big dog with long

pale hair, the colour of a Labrador. She was never meant to fit in any iron bin.

I tried one way, then the other, until the blanket fell off her head. Two black

eyes stared out of their sockets and seemed to follow me round. The way things

were shaping up I'd have been there until dark. Finally I managed to get the

dog's back legs in the bin. All the time I'd been pushing and shoving, strange

noises came from the dog's belly. In the end I hit it with me shovel and wedged

it in a forward facing position. Then I headed back to the yard. Sally in the

lead with vacant eyes.

The only way back to the yard from Assisi Street is through the shopping

precinct or around the ring road, which adds ten minutes to the journey. I was

in no mood for a trip around the district so I took the short cut, but it still

seemed ages before I was at the top of the precinct. It was packed with women

holding bags of groceries, the posh ones pulling wicker carts. Things would have

been all right only for this old woman wearing a cloche hat. She was as daft as

they come. Give the rest of the women their due, they moved over, dead nice

like, when they saw me coming. Some jumped into shops and others stood still

watching but saying nothing, like. Then outside the butcher's that old woman

heads for me. Everyone was watching her. She had a bit of paper in her hand and

was going to put it in one of me bins. There are still people like that you

know. I had to stop for her. She didn't even notice the dog at first.

"Thank you, son", she said, dropping the paper in the bin.

"All right, Ma," I said, ready to push off smart like. Then she saw the dog.

"That's a very nice dog you've got there. What's her name?"

"Sally," I said.

"Just taking Sally out for a walk, are you?"

"Yeah, sort of, Ma. She's not too good on her dolly pegs these days."

Well, what else could I say. Everyone in the precinct had stopped, even the shop

assistants were staring out of the windows.

"Well, Sally, I hope you enjoy your walk," she said. I knew she'd stroke the dog

when she pulled her glove off. The wizened hand seemed to take forever to touch

Sally. With long determined strokes on the dog's side and finally a good scratch

under the ears the old dear stopped.

"She's a very quiet dog, isn't she?" she said.

I didn't half think quick.

"She's a bit old now, can't even close her eyes when she sleeps." The dog's

stomach rumbled.

"You should take her to the vet, you know. I have a bit of eye trouble myself."

"More than you know," I thought. With a happy sigh the old dear left. I was glad

to see the back of her.

A sound like a bag of wet mortar being dropped came from the fruit shop. Mrs

Dixon had fainted. Just as I got to the end of the precinct, her husband, the

shop owner, came running after me. He was shouting,

"I saw it. I saw it all!!"

You'd have thought he'd been robbed the way he went on.

"I'll report you! I can report you," he kept saying. So I called the yard's open

phone number out without turning round. He wants to be a councillor and leads

all sort of crackpot committees that make beds of nails for Corpy bosses. The

best thing is that he sells second grade fruit at top prices and pays bad wages.

A typical dyed in the wool, small time Tory.

The two angels of doom were leaning on the wall outside the yard gate. The Bug

started,

"What was Rin-Tin-Tin's master's name?"

Then it was Manxie's turn.

"How many puppies did Lassie have in her last film?" The Bug said he didn't know

and that I was the expert on doggery. More laughs. I told them to get stuffed

and walked away. As an afterthought, the Bug said I was sacked. There had been a

phone call about me. The Bug never makes mistakes about things like that. Well,

if they were going to sack me I'd give them something to remember me by.

"Watch this," I said. Have you ever had a fantasy? You know, when you see the

hero in a film crash a car into a wall and then get out and walk away. Other

fellas can kill ten men and lay as many women in between. I think Tarzan's the

best. He's my hero, swinging from trees and wrestling lions that have no teeth

or claws. I made me mind up to give Simpson a nightmare to remember me by.

The container where we empty our carts is facing the office window. That's where

I parked mine. First I gave them a cracking Tarzan call to wake them all up in

the office. Then I pulled the dog by the collar from the bin and threw it on the

floor. It bounded back at me almost right at my throat but I just pulled away in

time. It was so real even the Bug and Manxie liked it and egged me on. Then I

slipped over and the dog rolled on top of me. What a performance! Uncle Jim had

to spoil it. He called

"Clancy, get in this office. Now!"

Simpson, the Inspector, was sitting behind the desk. The office smelt of

whiskey. He'd been on the bottle again. Uncle Jim stood behind me.

"Well, what have you to say for yourself?" Simpson said, hoping to bait me and

get things going his way. I wasn't having any.

"Can I have a new pair of gloves?" I said. "These have blood on them," then I

threw them on the desk in front of him. You'd have thought they were live sewer

rats the way he jumped up. The best about it was it was only tomato sauce from a

broken bottle in the container.

He shouted

"Get them off my desk!"

I picked them up.

"Listen, Mr. Bloody Clancy, I've had phone calls from half the shops in the

precinct. You've caused murder up there. People from the town office will hear

about this."

Just for a laugh I said,

"The dog was dead when I picked it up and it was you

that wanted it picked up anyway."

He said,

"My God! For what you did today, people have been locked up in lunatic

asylums for the rest of their lives." He had the pipe out of his mouth and was

pointing it at me.

"Don't take it in the wrong spirit, Boss," I said, hoping he'd take the hint

about his drinking. His eyes bulged and his ears were glowing red.

"Well, you won't be picking up any more dogs. You're sacked, Clancy!"

"Right!" I said. "I'll see you at the Industrial Tribunal and if I go, someone

will go with me."

Uncle Jim stepped forward and asked me to wait outside as Simpson started

screaming "Get out!".

I did and outside of the door I heard them talking. Uncle Jim was telling

Simpson that the last fella to take the Corpy to a tribunal walked away with two

hundred pounds in his pocket, and what would happen if he did the same. The

phone rang and Simpson kept saying,

"Yes, Yes. Right, Madam. Thank you."

When he put the phone down, Uncle Jim was at him again.

"He'll blow you up about

the drinking, Stan. He's a head case."

Simpson waited for a minute and then said,

"Go and tell him."

Uncle Jim came out and said I was not sacked after all and winked. The woman

whose dog it was had just phoned up and thanked the boss, saying how nice I had

been when collecting the dog. Then he went back into the office. I followed

after the door was closed. Uncle Jim asked Simpson what he was going to do with

me as I couldn't go back to the precinct beat. Simpson said,

"Well, if he's a

lunatic, a head case, I'll do what Napoleon did with them. I'll get a bigger

lunatic head case to look after a little lunatic head case."

All Jim said was,

"Not Sharkey?"

"That's right," Simpson said. "Now send the lad home."

Outside the gate the Bug and Manxie were waiting for me. They started howling

and barking when they walked over. I gave them the rest of the story and how the

woman had phoned the boss.

"She even gave me this envelope," I said. "Look

there's three pounds."

The Bug and Manxie started laughing and the Bug said,

"The phone call was from

the tart in the Betting Office. I made her do it for you. You don't think anyone

gives a monkey's for you. Christ! One born every day!"

Then Manxie put the bite on me, asking could I see my way to lending them a

pound each for services rendered! Well I always was a soft touch

John Small

ERNIE THE FITTER

Noo heors a tale ah canna vouch for as true

But it was towld teh me by one or two,

Of a fitter caalled Ernie a likeable lad

And the family o thorteen that he had.

Noo Ernies missus hadn't much time for leisure

Thorteen kids might be a dubious pleasure,

Seh noo and then teh give her a respite

She'd gan teh the bingo on an odd night.

Between eight and nine Ernie it is said

Thowt it time teh put the bairns teh bed,

Experience had shown shooting ne good at aaIl

Seh he blew a bugle teh soond thor recaall.

By one's and twos the kids drifted back in

Teh be clean washed as any new pin

Till just one black face was left ootside

Are ye coming in, wor Ernie then cried.

"Na!" says the bairn, Ah am certainly not

At which wor Ernie grew somewhat hot,

Gave pursuit and finally caught the mite

In the process receiving a nasty bite.

The bairn subdued met soap and toowel

His cleansed appearance made Ernie a fool,

His bairns laughed aalmost withoot pause

"Hey dad, thats not one o wors.

Dick Lowes

BRONCHITIS MK. II

Ellie stood handless as a relative at a deathbed as she watched them dismantle

Bronchitis MK I in a frenzy of spanners and wrenches. It came apart so easily

and Ellie saw its metal guts for the first time, spilled out in a tumble of

gears and rods and plates and screws at her feet. She thought it disappointing

that the source of all its familiar tempers and judders and jerks should turn

out to be this heap of cold metal pieces that couldn't muster a shine between

them. It was a sorry looking sight now that it was pulled clear of the assembly

line and stood in lonely glory in the aisle, with its flaking islands of paint

sticking defiantly to sheltered edges, its leads sprawling from its belly like

tree roots, leaning on its bent legs now that the support of the neighbouring

machine was gone. Ellie knew the history of each patch on its body, the

oversized lever that had replaced the original, the cardboard square where the

inspection plate had been, and the place where her tools hung, bearing light

patches, each the perfect outline of the tool which hung in front of it. The men

quickly captured and roped up the snaking leads, levered the whole lot onto a

trolley, shovelled the screws and gears onto the sides and suddenly, Bronchitis

I was gone.

Ellie turned to the space and picked up a brush. There was only a silhouette in

dust left now and she was loath to sweep it away and make the space truly empty.

People were looking at her though and she drew the brush across the floor

quickly and it was all gone. She went and sat with the girl at the next bench

and waited and presently heard trolley wheels again, also a speculative hum

advancing down the line, but she did not turn to look even when she felt her arm

brushed by a man's back as he worked the new machine into place. The men were

talking, advising, warning, taking care with the new machine because it was very

expensive and still wrapped in polythene, littered with printed cards saying

TAKE GREAT CARE. USE NO HOOKS. FRAGILE, and various other technical

instructions. Out of the corner of her eye Ellie saw the power lead wriggle

across the floor, bright new flex and a white plug. She shuddered. Then her

supervisor was at her side and talking to her.

"The instructress will be down in a minute to start you off. Dou you want to get

the feel of it? Sit down at it and look it over?"

As she could not put it off any longer, Ellie rose and nodded and looked at it.

It was smaller. The same shape near enough, but neater and sleeker, a glimmering

burnished silver thing with sharp square edges and a funny smell. Slowly she sat

down and began to examine

it. There were no levers, no foot switch, no clicking indicators, nothing to

touch except two buttons. ON and OFF. At eye-level a glass square looked at her.

Peering into it she saw dimly a black word. NIL. That was it. A hole at either

end and two buttons. Ellie's heart sank at its dullness and she sat wishing that

her wheezing, rackety Bronchitis I was in front of her and that she was

listening and guiding it through its work, coaxing it over its sticking stage

and banging on the indicator till it rattled home. The pitch of her longing

surprised her; she felt sick.

"Haven't you plugged in yet, Ellie?"

Ellie looked up at the instructress and grimaced. She bent under the machine and

pushed the plug into the socket and flicked the switch down. The machine buzzed

loudly and Ellie cracked her head on its belly as she jerked up in surprise,

Bronchitis I had been silent when switched on. The instructress laughed and

helped her into her seat. She stared at it amazed.

"Like bloody Blackpool!" she said, regarding the sudden appearance of coloured

lights in some awe. They were everywhere. Beside the two buttons, along the top,

inside the glass square which now pronounced NIL in a disapproving red glow, and

from inside the machine the buzz was now constant and anxious. When she leaned

closer Ellie saw that the machine was studded with glass squares behind which

monosyllabic information was offered. SET. MIN. MAX. CUT. LOW. OVER. She shook

her head.

"What's all that about?" she asked the instructress.

The instructress handed her a manual opened at a coloured diagram and Ellie

scanned the closely printed page in some alarm.

"Am I supposed to learn all that!" she asked indignantly, noting the number of

long words and symbols that dotted the page.

"You'll get used to it. It's easier than it looks. A lot of long words to

describe simple things as usual. Come on now, Ellie, they wouldn't give us a

machine we couldn't work, now would they?"

She was brisk now, anxious to get on with more important things and she appealed

to Ellie's pride in an attempt to get started.

"It's easier than the other old crock, all electric and all automatic. You just

shove a unit in here, check the indicators, press the ON button and out it comes

all done. It stops itself if anything's wrong. You try." she said.

Ellie pushed a unit in and stabbed at the button sulkily. The buzz deepened and

the unit appeared at the other end, finished.

"Simple as blinking!" announced the instructress.

Ellie stared at the unit in her hand, it was finished and yet she had heard

nothing, no click as it settled into place, no whirr as the air driver

descended, no bobble as it jumped out of the machine. It had all been silent

except for one little click as NIL rolled over to ONE. And her hands, just a

finger used, one prodded finger. Ellie was horrified.

"Oh no! I can't do this all day. I'll go nuts. I want to see the foreman. I'm

not doing this." she announced firmly.

In the end there was a discussion on the line. The supervisor, the instructress

and Ellie all talking in low voices, Ellie with some fervour, and it was agreed

that Ellie would try it for a week and then they would all see how things were.

Ellie agreed because she knew she would feel no differently a week hence and the

other two agreed because they had been allowed a flat two hours change-over time

and they were already ten minutes over that, and a week was a long time. Ellie

sat and moodily prodded her button and the units went in and came out in silence

and perfection - there was no need for Ellie's hookless tools - no hand repairs

- just the glow and hum and complacency of the machine and Ellie's finger. She

felt a bitter jealousy stir in her at the completeness of her dethronement, she

wished it would burst into flames or blow up or just die on her but it stayed

cool and efficient and accurate and disclosed no hint of a fault to Ellie.

She suddenly thought of her library book - a science fiction -about a world

where machines did everything and people did things like walking and reading and

dancing all day. Their machines had set them loose from work but hers had

brought her misery in a few hours. She knew very well that her finger was all

that was keeping her in her job and the knowledge came so hard and blunt at her

that she said out loud. "It's not fair!" The book was stupid.

She could not bear the futility it forced upon her. In that trial week her

fingers began the day loyal to Bronchitis I by reaching out for the lever and

the crank, and each day she kicked herself for not remembering when it hurt her

so to jerk herself back to its replacement and begin the weary prodding over

again. She could not trust it, nor shake off a fretting that took hold of her

more and more as the perfect units slid out of the machine and she looked them

over for some fault that was never there. With Bronchitis I she had felt things

happening, it had been loud and she had come to know the exact moment when each

stage was reached even though she could see nothing and did not know precisely

how it worked. But the Thing (she called it that, unable to bear christening it

with a thoughtful name) remained silent. It had only one other noise than its

buzz and this she had discovered when she poked a unit in back to front to see

if it was up to a little fight. Then the glass squares had blinked all together

and the belly of the thing had emitted a shrill angry whistle at her. Thereafter

she poked at least one unit in back to front every day just to hear its

indignation, sometimes prolonging the fault until her companions begged her to

right it and stop the awful whistle. The fretting continued and so increased

that she found herself so wound up that she had to switch it off and sit still

for a moment while she forced herself to calm down. She began to fear she was

turning out nothing but rejects, that real work had to be more effort, she took

boxes and boxes of units to the supervisor pleading with him to look them over

for her, and he became annoyed with her and told her to get back to work and

stop fussing. She had cried and he had been frightened.

She couldn't sleep for frustration plucking at her muscles. Her husband had

wakened, ill-tempered, and snarled at her.

"For Crist's sake, lie down and be

still!" She nudged him.

"Tom, I want to leave the factory. Get another job.

"There was a short silence before he mumbled.

"We can't afford it." and fell

back into sleep noisily.

"That's another daft thing about that book. Where'd

they get the money from for dancing all day?" she said to herself in the

darkness. She laid down and tried to be still.

They all sat together in the tiny office, the supervisor, Ellie, the

instructress and the foreman. The foreman had offered cigarettes and was fixing

a genial smile into place before he spoke. Ellie looked miserable and the

others, concerned.

"Now then, what's the trouble Ellie?"

She shifted in her chair, too miserable to speak and the silence embarrassed

them all after a few moments so there was a rush to speak and a tangle of words,

then a short polite silence before they all rushed in again. The foreman hauled

out his authority.

"I understand the new machine is giving you trouble, rather, causing you some

distress, Ellie?" Ellie nodded mutely.

"Don't you understand it? Surely, Mrs Peebles here, showed you how it works. I

understood it was automatic. Has it been having teething troubles, anyone?" he

asked them all.

"Oh, I showed Ellie but I have to say that she didn't . . well like it from the

start. It's really very easy to operate and there's been no stoppage due to the

machine." the instructress finished.

"Her work's fine. Target's up of course, with it being so much faster than

Bronchitis 1 . ."

"Faster than what . . . !" interrupted the foreman.

"Bronchitis 1. My old machine. It was a real machine." Ellie said flatly.

"Compressed air." explained the supervisor. "It wheezed".

"Oh, I see ... well, look Ellie, can you not explain what is wrong. We'd like to

help." the foreman asked gently.

Ellie straightened herself in her chair and looked hard at him. He was smiling

encouragingly at her. She took a deep breath and spoke slowly, like an advocate

assembling facts.

"Bronchitis 1 and me worked together - we were both important. I had to wind him

along and watch him and he had to punch the units. You had to know him - you had

to earn the right to work with him, by knowing the job and understanding him. My

hands, well, my hands knew the job, they listened to him and knew when he needed

a bang on the box. I felt him working. But now, I push the button and the

electrics take over. I don't know what I've done. Christ! A monkey could do what

I'm doing now and you wouldn't have to pay a monkey. I'm taking home pay for

nothing and it's like I was stealing. I've no respect for myself. I used to feel

tired at night because I'd worked all day and that meant I'd earned my money. I

want off that job . . please." she finished in a low voice and her emotion

filled the office as if it were a gas cloud stunning them. Such an appeal was

unheard off in these surroundings - human to human, and the three listeners,

threw their frantic gazes out of the window while their identical lumpish

throats swallowed furiously in the silence.

"Okay, something mechanical, I think. Ellie, we'll work it out today and start

you somewhere else tomorrow. We can't get Bronchitis back now, unfortunately.

Run along." the foreman said to her departing back.

"Funny sort of girl that, she made me feel ashamed of something for a moment.

Silly." he said to the supervisor, trying for their usual masculine conspiracy.

"You don't think when they say you can have some new plant that it might

interfere with things like this. I remember ordering that machine."

The supervisor faced him frowning.

"Just the same, someone's got to work it, and tomorrow since you let Ellie off

from then. What if it happens again?" he asked worriedly.

"It won't. She must have been the sensitive type. Transfer one of your

wooden-tops, one of the ones that can't tell left from right properly, someone

who's doing something dead simple just now. And we'll take it as it comes after

that. Okay?"

Next morning a new girl sat at the machine. The instructress was with her for

five minutes and after that the girl prodded the button every twenty seconds

throughout the day, fascinated by the glowing lights and the soft buzz of the

machine. So pretty after that spitting solder bath, so quiet and dreamy, cushy

job this, she thought, wonder why that other girl left it?

Ellie sat two lines up, bent over her hands, flexing the fingers around the unit

she held, using them all as she tweaked, prodded, poked, wound and twisted

multi-coloured leads into place slowly and with loving care. Eyes, ears and

fingers taut, she felt her face uncrease as the pile of completed units grew and

she saw already, that her units were recognisable in the pile by the way she

twisted her leads, a little tighter and closer than the others. It was like a

signature, Ellie's work, something that was hers and she was responsible for. A

little way off the supervisor watched her and saw from the smooth arc of her

spine that she was engrossed and content. "Daft bitch." he said to himself.

Vivien Leslie

FUEL

Today there are still many Hamans

And Hitlers and Francos

But for each one of these you will find

One million men and women whose own

In-built motors are run on the milk

Of human kindness

ROSE FRIEDMAN

PASSIVE PITY

Passive pity

Without action

Is an empty luxury

With benefit

To no one -Not even

To the donor

STARRETT ON ITALY

LA DOLCE VITA - A letter from Bob Starrett

Dear Rick,

By now you'll have seen by the post mark, that I'm living in Italy. Why? Well

it's one of those events that take place in my life periodically between long

periods of routine behaviour. I'll call it artistic temperament. (Wee Boab isn't

as contained (?) as his west of Scotland Calvinistic background would have

people believe).

The truth of the matter is that for more years than I want to think about I've

always wanted to spend a bit of time in this part of the world - Artwise

Well, an Italian comrade visited the Byres Road during the summer and I asked

him if there was anything doing that I could handle.

I forgot all about it.

However, a couple of weeks back, he sent for me with, as they say, an offer I

couldn't refuse. It's guarding an ancient Villa full of neoclassical junk that's

awaiting auction in about a year's time. I've to wander through the junk filled

rooms at night arid check the seals on the doors. It takes a bit of getting used

to. But patrolling the grounds at night is the experience of all time. Being a

city slicker, I had always assumed that night time in the country was fairly

quiet.

Well, have you ever heard an acorn crash to the ground in the dead of night, not

to mention autumn leaves following you around, being blown by a slight breeze

that wheezes in fits and starts like an old man. Aye, Rick, in times like these

I'm glad I'm a Marxist - as for robbers, well, I'm armed with a Winchester

Repeater, and at times I would rather face robbers, at least they're from the

materialistic world, whereas the dark side of nature is beyond my ken.

Which brings me to a subject that should interest you. Because of the language

difficulties (The inflections, the dialects, the hand language etc) it's a

constant strain to listen to everyday conversation. Indeed, it's like

experiencing a deluge of words and you're trying to catch one drop as a starting

point. The outcome of it is that one's senses are heightened to such a degree

that it's like hearing words for the first time in one's life. In just such a

frame of mind I read Hugh MacDiarmid's Drunk Man Looks etc. It was a knock out.

Whereas previously I had skimmed the surface of the words, with my new awareness

of their sounds, meanings etc. the poem was a real emotional experience. Imagine

having to travel to Italy to understand one's own language!

A wee bit of spiel about my position here. - Seeing so much beauty after 7 1/2

years looking at bloody war ships is too strong a diet. I went out last Sunday

with a comrade, and the first little hamlet we passed through was absolutely

beautiful, so much so that I wanted to photograph it right away. Then we passed

another of different style but equally beautiful and another and another and

another It was visually the equivalent of a

kid being let loose in a sweet shop, and the feeling of nausea was just as

strong at the end of the day. On TV last year, during a three part series about

a dreadful housing estate in Glasgow, "Lillybank", a councillor remarked that

"there was a pain felt by so long looking at downright grey ugliness". Well, I

have just the opposite. We dined on trout antipasto, trout spaghetti, roasted

trout I hadn't had a trout in years, (too

expensive in Scotland) and here we were eating them in surroundings of

indescribable beauty, (the mountain peaks were all capped with snow a la tourist

posters) and everyone round the table a communist. I remarked on the difference

in lifestyles between our two countries and indeed, between our two parties.

They laughed -hedonists to a man. This is not the home of the Dolce Vita for

nought!

Everyone is armed to the bloody teeth. The bastards shoot everything that takes

to the air. Someone said that "you could judge the freedom of a country by the

right of the populace to bear arms." It's some contradiction.

This region has one of the highest living standards in Europe. My own wages are

fantastic. Food is cheap as it's an agricultural area. Someone told me that the

place had the highest amount of motor cars per capita in Italia. Well, they

didn't need to tell me really -had already attempted unsuccessfully to cross the

road!

Now I hope to continue working with Brian and yourself Rick, but there may be a

difficulty getting my brain sorted out to do any decent work. My cartoons depend

on being abrasive and it's a difficult emotion to generate after you've dined on

a five course meal. But it's my wish - one would have to take into account the

Italian postal service which must be the worst in the world. But given plenty of

time we should be able to work something out.

I was getting myself fit before departing and as you know, you don't want to

lose the fitness once you have attained it - it's too bloody hard earned. I was

enquiring about bringing a racing bike over here and honestly the faces on the

guys registered complete bafflement. Why anyone would want to push their bodies

through any kind of hardship was beyond them. A comrade, Renzo, who organises a

cycle race annually for the town told me that all the leading cycle racers argue

over the course, the amount of prize money etc., and he told me, to a man, they

all hate the game. They hope to win a few quid and open a wee factory or

something. The guys he mentioned are my idols too!!!

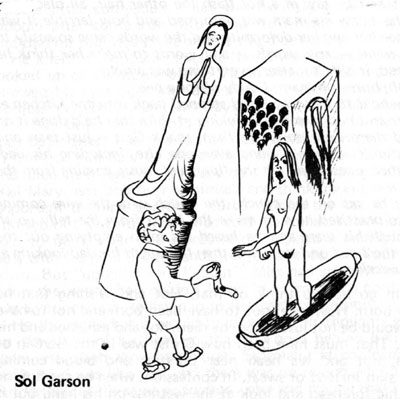

The illustrations I've included, Rick, maybe will be too parochial for your

readers, but they accurately reflect the position of a shipyard punter facing

new experiences.

The illustration showing me at a typical Italian table is based on a visit I

made to a farm house in the village of Petriolo. It was typical Italian and the

people had worked the land for years as their people did before them, indeed the

house itself was at least 200 years old. They were party members of longstanding

and I looked for the usual 'clues' to back that up. But it was all so very

different from back home. The Tele had a curtain round it like a theatre (which

is maybe the idea) and I've included that in the sketch. From the ceiling clung

all kinds of salamis etc and yet the only visual on the walls, which were all

stark white, was a print of Micky Mouse - I've entitled the illustration

'Cultural Imperialism'. But you know all that.

The drawing depicting me as a prisoner of the Villa is near the mark as to what

a creative person feels who for one reason or another they can't 'take part' or

fully understand their environment.

I see Voices still has cash difficulties. Aye, the UK is free all right - if you

have the dough. But it's one of the few publications that exist for workers to

express themselves which isn't infantile, so it must survive.

Yours aye,

BOB

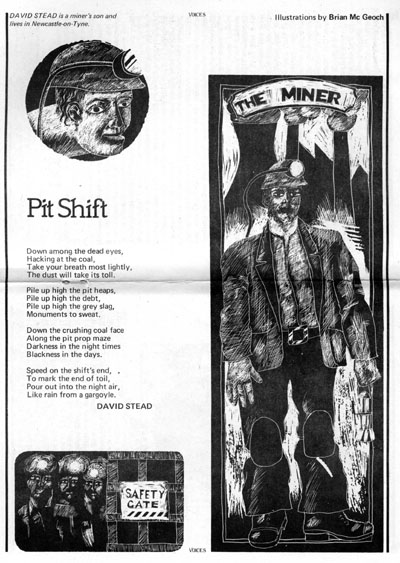

PIT SHIFT

Down among the dead eyes,

Hacking at the coal,

Take your breath most lightly,

The dust will take its toll.

Pile up high the pit heaps,

Pile up high the debt,

Pile up high the grey slag,

Monuments to sweat.

Down the crushing coal face

Along the pit prop maze

Darkness in the night times

Blackness in the days.

Speed on the shift's end,

To mark the end of toil,

Pour out into the night air,

Like rain from a gargoyle.

David Stead

CONFESSION

Soon, if he tried to be very holy, the statue would start wobbling. It had

always wobbled. Sometimes before confession it wobbled and sometimes after

confession, but it had always wobbled sometime.

He knew he wasn't a saint, like, but he felt sure that the statue of Mary didn't

wobble for everyone. He couldn't ask anybody, though, if they saw it wobble

because if they didn't they'd laugh at him or tell him that he only thought it

wobbled and that it didn't really. Maybe that's what the saints thought when

they saw all the holy things but it didn't stop them from telling other people

about it. But he wasn't a saint and he wasn't brave and he was going to keep

quiet about it. Anyway so far it hadn't wobbled. He liked it when it didn't

wobble before confession cos he could look forward to seeing it wobble after

confession. That was exciting. And when he saw it wobble after confession he'd

know he'd made a Good Confession and that his soul was white and he could be

happy.

He knelt in the queue outside the confessional and now and again looked up at

the statue of the Virgin and then bowed his head and screwed his eyes tightshut

and tried to prepare himself for a Good Confession. There were two boys before

him. That was alright, to have two boys before you, cos you didn't have to try

too hard to shut out noises. You had to shut out noises. When there was nobody

in front of him he'd be able to hear the confession of the boy inside and then

he'd have to try very hard not to listen and he'd say the Hail Mary over and

over to himself and think upon the words. It was important to think upon the

words. "Upon the words" didn't mean on top of the words". Miss had told them

that. When he'd first been told to think upon the words he'd imagined a man

lying sprawled out, with his chin in his hands, on top of those big lit-up signs

down town. But "upon" meant "about", Miss had said. When he thought upon the

words he couldn't listen in to another's confession. That was a very bad sin, to

listen in to another's confession.

He thought what it would be like if all his thoughts were written on the back of

his head so that the boys behind him could read them. He often thought of that.

Especially at confession. Nobody else's head was like that and there was no

reason why his should be but he wasn't the same as anybody else and maybe that's

what it was that made him different and maybe nobody wanted to tell him. Maybe

they just read what he was thinking about and laughed at him and talked about

him behind his back because they wouldn't ever think about the things he thought

about.

His mam was in the back kitchen getting a bath. She'd told them all. When his

mam or dad or any of the grown-ups were getting a bath- in the back kitchen he

couldn't go to the lay. The lay was in the back yard and he had to go through

the back kitchen to get out there and when they were getting a bath he couldn't.

He'd been watching the telly. Wyatt Earp: Wyatt Earp, Wyatt Earp, brave

courageous and bold. Long live his glory and long live his fame

And long may his story be told. and maybe that's what made him forget.

He opened the door and heard the splashing of water in a bowl and the splashing

of water on an oilcloth floor and the slapping of a foot on a wet floor and he

smelt the smell of lifebuoy and cool air, all at the same time, and he saw his

mam there naked with her head and neck flashing around to look at him through

her hair. She was stooped over, drying herself, with the towel between her legs

and her hair all wet and tatty and long and black falling down nearly straight

to her waist and he saw in a hot flash the other hair, all black and curly, and

he knew his mam was deformed and how terrible it was for him to see her and her

deformity and the words came so easily to his heaving mind - any words - any

words to make her think he hadn't noticed, it didn't matter, everything was

alright:

Oh, hurry up mam; I'm dyin' for a pee.

And already he'd turned away and stepped back into the kitchen as he heard her

and half saw her shrieking at him that he'd done it on purpose and there were no

words then, thank God - just tears and crying, "I didn't. I didn't", and

everyone else, including his dad, quiet with their eyes down on the floor and

music coming from the telly.

And then he sat on the couch, the couch with the wire coming through, and

practised how to make the lights from the telly go all pointy through his tears

and he heard his mam emptying out the water from the bowl and now and then he

caught his dad looking at him and wondering.

It made him go hot to think of that. Hot and wishing that he hadn't been born.

How nice, not to have been born and not to have to die. He would be hot just

before he died; hot and ashamed and his head heavy. That must have been how

Christ was in the Garden of Gethsemane, hot and his head near bursting and blood

coming through his skin instead of sweat. In confession, when he got hot, he

would feel his forehead and look at the wetness on his hand but it would always

be sweat and he would draw a cross on the palm of his hand with his fingernail

and the dirt and the sweat.

On Saturdays he did the bedrooms for his mam. He liked to do the bedrooms and

see the beds all made and no fluff underneath them and the sticky bits on the

oilcloth all mopped away, and all because he'd done it. And afterwards he'd show

them to his mam and she'd be pleased and say to everyone how they ought to see

those rooms now, how spotless they were.

That was a reward on earth, to hear his mam say that, so God wouldn't take much

notice of it but it was nice, anyway, to hear it and probably everyone wanted to

hear things like that when they'd done something good.

He thought it was good to bring the bandage thing down with the dark-red stains

on it. He got hold of the little hoop and carried it dangling into the kitchen

and his mam saw it and screamed at him to mind his own business and grabbed it

off him like it was a rat and ran with it to the back kitchen and he started to

cry and ask what it was and everybody turned away and pretended to watch

"Grandstand" and he knew it was something to do with the other hair he'd seen

once.

It was Bunloaf hearing confession, Tommy Poach passed on the message as he was

going out. Bunloaf once gave Stevie Thompson nine First Fridays for a penance

and everyone said that Stevie must've been wanking and they laughed and he

laughed too but he didn't know what they meant. Wank sounded bad and sponk

sounded bad too and they said sponk a lot. Sponk sounded smelly. Like a poe the

morning after.

What would you do if you got nine First Fridays?. Would you have to do them all

before the sins were forgiven? That meant nine months of living in a state of

mortal sin, and if you died before the nine months you'd go straight to Hell.

And you couldn't receive communion before the nine months were up. Stevie

must've done them all cos he was receiving communion again now. That meant

Stevie wouldn't die without a priest being there. That was a promise they made:

do the nine First Fridays and there'll be a priest at your death. How could they

be so sure about that? But it was true cos otherwise they wouldn't have said it

and if it wasn't true then the wife or the child or the parents of someone who'd

done the nine First Fridays and died without a priest would have come along and

told everyone that it was a lie. And nobody had said it was a lie. Sometimes he

wished that Father Bunloaf would give him nine First Fridays and then he'd have

to do them and then he'd be sure of a priest. He'd tried to do them, like, but

the furthest he ever got was Four and that was no good cos you had to do them

all in a row. Consecutive, they called it.

His mam and dad had never done the nine First Fridays and they never went to

mass. He wasn't ever going to get married until they were dead cos he wanted to

be sure they got a priest when they died. His dad coughed a lot. How could

Heaven be nice if you were there and your mam and dad were in Hell? The priest

said that then you'd see how wicked they were and how much they deserved to be

in Hell and that they would hate you for being in Heaven. He couldn't understand

that and he didn't want to see his mam and dad in Hell and he often cried about

that, alone in bed, and prayed to God that they'd get their faith back or that

they wouldn't die without a priest.

His turn was next. He thought upon the words of the Hail Mary:

Hail, Mary, full of grace.

The Lord is with thee.

Blessed art thou amongst women

He didn't stutter when he prayed. Praying was like singing and

he could pray and sing and not stutter. His stutter had been blessed by the

priest three times now and still he stuttered. His brain worked quicker than his

mouth, his mam said, and that was why he stuttered. But that wasn't why really.

"Nine o'clock mass and holy communion" was very hard to say. He had to say that

every Monday morning when Miss took the mass attendance register. He said "nine

o'clock mass and holy communion" even when he hadn't been to mass at all.

Everyone was expected to go to nine o'clock mass and holy communion. Some lads

said that they hadn't been and that was very brave. Miss got angry sometimes

even if you said "ten o'clock mass and holy communion". Ten o'clock mass was for

grown-ups.

One Monday after a Sunday when he'd been to nine o 'clock mass he told himself

that he wasn't going to stutter over it and God was going to help him not to

stutter cos he'd be telling the truth, and he was sure of it as Miss went round

the class and then it got to his turn and his teeth went together to say "nine"and

the muscles in his jaw hardened and started to ache and his arm went straight

out and came crashing down into the top of his leg and then straight out again

and then crashing down again as he tried to get out the "nine" and all the time

he was making this choking noise from the back of his throat and it felt like

the noise was coming from his ears and the sides of his head and nothing was

getting through the teeth and then with the last breath in his body he sort of

gasped out "nine" but so low that Miss couldn't hear but she pretended she did

and then he drew in his breath again for the "o 'clock" and some of the class

were laughing and some were looking down at their desks and Miss was looking

hard into her register.

He could hear the sound of voices in the confessional and the rustle of paper

from the queue behind him and giggles from the queue. It was important to

prepare himself, to think upon the words:

And blessed is the Fruit

Of thy womb, Jesus

He went to confession every four weeks, with the school. Once

there had been a holy day and he'd had to tell the priest that he'd missed mass

five times and the priest had asked him how he could miss mass five times in

four weeks cos the priest had forgotten about the holy day. The priest had

laughed then too. It was alright when he'd missed mass four times, and those

five times were alright, cos he could say four and five easily. Once he had

missed mass three times and he couldn't get "three" out so he'd changed it to

four. That was o.k., to say you'd sinned more than you had, it was only telling

less that was bad. When you told less your sins weren't forgiven and you got an

extra sin on top of them as well, a sacrilege.

Someone was poking him in the back. They wouldn't have liked being poked in the

back if it had been their turn next. Maybe they could read his thoughts on the

back of his head and they were going to tell him how stupid and dirty he was. He

could hear the rustle of paper right behind him and the boys were talking more

loudly now and saying something about Stevie.

Holy Mary, mother of God,

Pray for us sinners now .

But it was no good. He couldn't think upon the words anymore

and he turned to see what they wanted him to see. A Manchester United wall

chart. Stevie had got a Manchester United wallchart. Nobody he knew had ever got

a Manchester United wallchart and everybody wanted one and now Stevie had got

one. They only put one Manchester United wallchart in for every ten of the

others; they said that didn't they; it was written on the chewing gum packet;

and now Stevie had got one.

He opened it up and looked at it and he could see the creases in the paper where

it had been folded and they made sort of oblongs, like little football pitches,

and he thought if he pulled it a bit it would tear down one of the creases and

that would wipe Stevie's eye for him, but that was a sin, to think that way:

Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour's goods.

And he hated Stevie for giving him another sin to confess and that was another

sin as well cos you had to love others as you loved yourself. He tried to think

upon the words again:

And at the hour of our death .

but he couldn't; he was looking at the wallchart, all red and

white, and at the young men all smiling back at him, and he looked especially at

the ones who'd just been killed, and how nice and sort of shiny they looked, and

he felt himself smiling cos they were dead, and he felt his dick sticking up on

end in his khaki shorts.

That was it then; he knew. No Good Confession now and the statue of the Virgin

wouldn't wobble afterwards. It was o.k. about hating Stevie and being jealous

and even that funny smiling but he couldn't tell the priest about this other

sin. The priest would think he was a monster or something cos no priest ever got

a hard one on about footballers, leastways not dead ones.

His head was cold now and his stomach kind of cold too and the cold sweat came

off his hands as he folded up the wallchart and passed it back down the line.

Someone came out from the confessional and tried to nudge him over as he was

getting up off his knees and that meant that, if he didn't go over, he could

grab the balls of the lad who bumped him; that was a sort of rule; but he never

did that and he didn't do it now and he went into the confessional and breathed

real deep and shut the door and started almost singing as the door shut:

Bless me, father, for I have sinned.

It is four weeks since my last confession and I have

And that was the easy part over already before his knees had hardly touched the

little cushion:

M.m.m.missed mass four times, father. T.t.taken the name of the L.L.L. . .

Lord thy God in vain, child?

Yes, father, stolen things, father .

What kinds of things, my child?

Sw.. Sw.. sw

Sweets, child?

Yes, father, from Woolies, father.

And he had used bad language and failed to honour his father and mother and he

had been jealous of Stevie:

C.. c. . c. . coveted my neighbour's w. . w. . w..

Wife, child?

Wallchart, father.

Of course, my child. Anything else?

The priest didn't laugh at that. The priest was running his hand through his

hair and all he could see was the dark-redness of the priest's bare hand and the

black outline of the face behind it and the little bits of dust and dandruff

that came spinning off the priest's hand into the light from the little window

above. But it was Bun loaf, alright.

Yes, child, anything else?

It was Bunloaf alright. He wouldn't know who he was but he'd know it was someone