|

ISSUE 19

cover size 210 x 148 mm (A5)

Editorial Michael Rowe

Knowhow & Wisdom Mary Casey

The Clinic Vivien Leslie

The Better Half Maureen Burge

A Bag on the Beach Pat Dallimore

We Survive Keith Stephens

Where I am Coming From Lynford Sweeney

Skindeep Lynford Sweeney

No Fixed Abode Bev Shaw

Snowdrop Man Blackie Fortuna

The General Strike B. J. Hill

Winnie Be Damned! Sean Damer

To the Thirties Donald Bishop

Strike One! Stan Cole

The Subby Tommy Walker

The Class Game Mary Casey

Shift Worker's Lament William Hunt Vincent

Ode to Winter Arthur Adlen

The Last Shift Victor Irving

Factory Floor Poem No. 2 Victor Magor

When the Soldiers Came Joe Smythe

Bomb Disposal Phil Boyd

For Freedom R. Carpenter

The Psychiatric Unit John Gowling

Break for a Commercial 'Crispin'

Child Watching Joe Sheerin

The Good Old English Bobby Tony Chesney

Me Too! Bill Eburn

Free Speech Bill Eburn

Found Poem David Carr

EDITORIAL

Judging from

the feedback we have had from the last few issues, our Readers seem to be of the

opinion that "Voices" is going through a period of change, for better or for

worse. As usual, our Readers are quite correct.

During the

last eighteen months there has been a great upsurge in the Worker Writers'

movement, culminating in the Working Class History, Culture, and Community

Workshops around the country joining together in The Federation of Worker

Writers. "Voices" has played its part in the founding of the Federation from the

outset, and will continue to do so. Running parallel to this it has been proved

necessary that if "Voices" is to continue as a regular well turned-out

publication, the editorial and publishing must be run on a full collective

basis. Hence the new Editor for this issue and the new address.

At the

"Voices" General Meeting on the 1st November 1978 a new constitution was

formulated, (see inside back cover), enabling us to function as a collective

without breaking the continuity that has enabled us to establish a solid

identity of "Working Class poems and prose with a Socialist appeal".

Regular

Readers will also notice that we no longer carry the "Unity of Arts" masthead.

It was decided at the above mentioned meeting that as "Voices" is all that

remains at present of "Unity of Arts", we should in future go ahead as an entity

in ourselves. Although we remain firmly committed to work for the implementation

of TUC Resolution 42 of 1960.

In the long

term we hope to be able to obtain funding for a full-time worker, thus enabling

the responsibility for each issue to rotate around the country.

With the

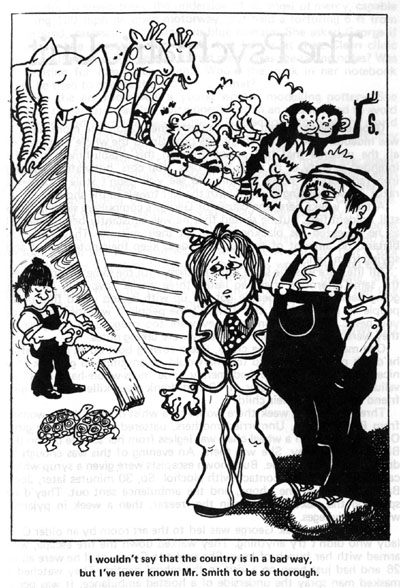

departure of resident cartoonist Bobby Starrett to Italy for a year we are

running short on Illustrators. We'd like to hear from any Illustrators and

Cartoonists around the country who fancy getting involved.

This year

we're hoping to get back to putting out four issues per year. It should go

without saying that we need feedback from our Readers to keep us on the right

course of providing an outlet for Working Class poems and prose, so let us know

what you think even if it isn't all complimentary.

Michael Rowe

KNOWHOW AND WISDOM

There is "knowhow" and there is wisdom,

these are worlds apart,

For "knowhow" lives within the head

and wisdom in the heart.

If the trees of science

are not tended with great care,

the bitter fruit of intolerance

will bloom profusely there.

Planners with great "knowhow",

will bulldoze the friendly street

replacing them with warrens

Tall towers of concrete.

Splitting friendly neighbours

into isolated cells,

Then bring in the psychiatrists

to hush the lonely yells.

they will gird the country lanes

into an asphalt yoke

isolating the country

from the country folk.

they will mix their noxious lotions

to further their own ends

polluting all about us

with their baneful blends.

They have tamed the mighty atom

and caged it just in case

they need its grim precision

to wipe out the human race.

The arrogance of "knowhow"

can crush the human heart

When knowhow rules compassion

wisdom will depart.

and the humble individual

will fall along the way

Mid data and computers

if knowhow rules the day.

Mary Casey

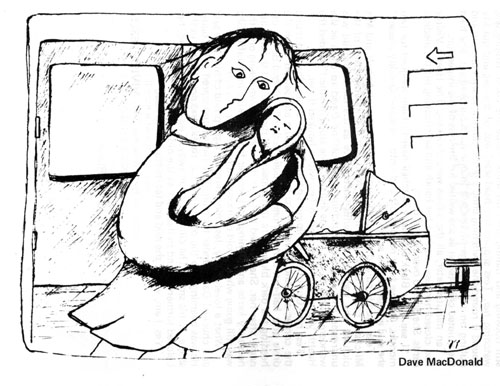

THE CLINIC

Tess always

parked her pram beside the dustbin, as far away as possible from the gleaming

chromium ranks that flanked the clinic doors. For all the hours of rubbing at it

with Duraglit, her coach-built monster never managed to take a shine a few

degrees above shabby and, she told herself, it looked more at home with the

dustbin than with its streamlined descendants. There was, however, nothing

shabby about its occupant.

Little David

twitched inside the bubbled wool of his pram suit. Nine months old, bonny to the

point of splitting his skin, he was just coming out of sleep with a gargle of

sounds that described his contentment. Tess kissed the child and bundled him up

in a cover before entering the clinic with him. Inside there was the usual

confusion of half-dressed infants and pin-biting mothers, interspersed here and

there with the dark blue authority of the Health Visitors as they ministered to

their prey. Tess could hear a shrill command above the conglomerate noise in the

hall.

"New mothers

assemble here, quickly now!"

She watched

as those summoned confirmed their status with awkward walks on chaffing legs,

clutching small bundles to their ballooned breasts as they assembled obediently

on the spot indicated. Tess took a seat beside the remaining women, the

initiated who wore their mystique with a conspiracy of mutual calm. She sat

David on the mat and loosened his covers. He grinned.

The women

beside Tess were already deep into conversation, eyeing each others' children

with critical eyes, noting the squints and spots, weight and clothes, as they

talked. Tess could not interrupt. They were into a discussion of meals, meals

for husbands, and she had nothing to offer them. They knew, of course. In spite

of the amplified bellowing a thoughtful Health Visitor summoned her with,

lingering over the "Mrs" with deliberate emphasis, they knew she had no husband.

At first, they had tried to steer their conversation onto neutral ground for

Tess' sake, being kind enough and glad enough of their own situations, they had

shown some embarrassment at demonstrating their respectability in front of Tess.

After awhile, when Tess responded with less than gratitude for their generosity,

they had begun to ignore her. Tess didn't mind that, it was less piercing than

their kindness.

It was easier

for her to be solitary there, clutching her pride and independence to herself,

not letting them suspect her envy and loneliness. Kindness unnerved her and made

her rawly aware of her situation. Her solitude allowed her her fantasies, her

subjective interpretation of her problems and her secret distrust of their

babbling contentment. She sandbagged this artificial smugness with their cliches.

Unaware, they cluttered their chatter with rich finds for Tess' desperate ears.

There was a

scuffle at the door and their Health Visitor walked in, tossing case and coat

into a heap behind the desk, on which lay the files. "Afternoon mothers!" she

yelled and theirs was a dutiful response, ridiculed but made never the less. She

scanned the charts. "Jabs today," she announced with some enthusiasm that made

the mothers wince in anticipation for their smiling babies.

Tess removed

David's nappy covertly, suspecting and finding it soiled. She rummaged in her

bag for a tissue and wiped his buttocks clean. She was about to set him down and

go to the sink to wet another when the Health Visitor bellowed, "MRS Black!"

Tess hesitated and started to speak, to tell her that she wasn't ready but the

woman had already picked up David and was peering into his eyes in search of a

squint. "Come along, come along, MRS Black. No time to dawdle! Is he eating?

Sleeping? Crawling yet?" she fired the questions at the stuttering Tess, who

answered each and tried to warn the woman but she wasn't listening. She was

already unwrapping a syringe from the case and adjusting the dose of vaccine.

"He's got a

dirty bottom!" Tess had shouted to override the stream of feeding instructions

that rolled out of a practised mouth and had stopped just a second before she

shouted. Her voice rattled across the hall, drawing heads towards it. There was

a moment of silence while the Health Visitor stared in sudden alarm at Tess.

"Well, clean it!" she said, and shrugged an ear-high shrug that shamed Tess into

haste and she ran blushing to the sink and sprayed water all over herself before

she managed to control the jet and wet the tissue.

Every one

there was looking. Tess could feel their massed stare on her back and the

pointless humiliation brought angry tears to her eyes. She washed David's

upturned buttocks with shaking hands, clumsy in her misery she almost rolled him

off the narrow table and the exasperated sigh this brought from the Health

Visitor, shook her further. She could only watch in agonised sympathy as the

woman plunged the long needle into the child's thigh and wince when the

momentary lapse between contact and reaction had passed and the child howled

with shock and outrage. Tess held the screaming child to her, hiding her wet

face in his redraging one as she walked back to her seat. She sensed rather than

saw the shudder that jerked through the waiting women.

Tess felt in

the bag for a clean nappy. It wasn't there. For a moment she sat in dumb

surprise, picturing herself laying it out. She looked over at the other women,

wondering which one would have a spare one to lend her and wouldn't tell. She

couldn't put David down to ask. He was still howling and flailing with his limbs

inside the cover. No-one was watching her. Tess slipped her head-scarf out of

the bag and quickly bound it round the twitching child's groin, pinning it with

one pin and pulling on the leggings of the suit in one furtive movement. She

held the quieted child to her as she waited for the rest of the inspection.

Ten minutes

later, all the babies were shrieking: The Health Visitor had closed her case,

washed her hands and sat checking off the medical cards. She paused over two of

them.

"I see baby

Black and baby Mitchell haven't been weighed for two months. Can we have nappies

off and onto the scale? Quickly please!" she said and pulled the scales out.

Tess

shuddered and panicked, aware of the eyes on herself and Mrs Mitchell, casual

eyes that merely followed the moving parts of the picture. She watched in awful

uncertainty as the Mitchell child was undressed and weighed, clutching the

snuffling David to chest as she wondered what to do. "Come along. Come along,

mother!" chided the Health Visitor, and beckoned to Tess with a hooked finger.

Tess ran. Out

of the clinic with neither bag nor cover. She fled round the corner and laid

David in the battered pram and set off down the drive at a half-run that bumped

the delighted child up and down, unheeding the dark blue figure that appeared at

the door and shouted her name after her. She walked half-way through the town

seeing only the necessary kerbs and turnings to keep her from walking into

traffic. She was still going when an old man stopped her.

"What a

lovely baby, lass. You must be right proud of him," he said and chucked David

under his chin. Tess halted and stared at her baby. He was beaming into the old

man's face, cheeks and nose lighted in the shape of his smile. The clinic was

far away. Tess looked at David, her beloved tormenter, and smiled back at the

old man.

"Yes, I am,

very," she said and let its truth in to heal.

Vivien Leslie

THE BETTER HALF

I'm the little woman

who sits at home and waits

While he's out every evening

boozing with his mates

He thinks that I should be content

to stay at home each night

While he's off at his meetings

to set the world to rights

But just you wait I'll show him

He can't mess around with me

Yes just you wait until

I pass that G.C.E.

I'll get myself a bloody job

I'll earn a few more quid

Then we'll see who stays at home

and minds the bloody kids

Maureen Burge

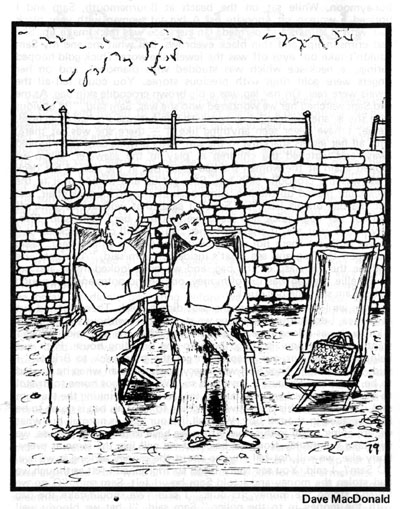

A BAG ON

THE BEACH

One day

during the schools summer holidays, mother had taken my two sisters and myself

to Weston Super Mare for a days outing. We had been there all day. The three of

us girls had been swimming, had ate fish and chips and lazed around on the

beach. It was about six o'clock and we were still on the beach as though not

wanting the day to end. The beach was clearing of people, who were beginning to

make their way home. But we were still there. My mother would let us girls stay

for as long as she could, making the happy day last as long as possible. The sun

was going down in the sky, the dirty sea water at Weston Super Mare didn't look

dirty. It looked clean like a lake, peaceful with the sun shining on it as the

tide lapped gently in shore. Mother was sat in a deck chair with us three girls

sitting on the sand near to her. Then mother told us a story.

"When I

worked in Wills Tobacco factory, I got friendly with a woman there, her name was

Daisy. She was a nice woman, very quiet and refined in her ways. Daisy and I

would sit together when we had a tea break. It didn't take long before we became

good pals. Over a period of time we got to know more about each other. I told

her I had three daughters still at school, and that my husband was a docker.

Daisy told me about her life, how she was a widow. Her husband had been dead for

two years, that she had a son at university who was studying to be a doctor. One

day at work as we were having a tea break, Daisy said to me, "Nellie would you

like to come to tea at my house. There is something I would like to tell you,

something I have never told anyone. I want to talk to someone I can trust." So

we made the arrangements and on the Sunday, I went to Daisy's house to tea.

Daisy had her own house not a council house. It was a very nice house with bay

windows and a well kept garden. Daisy opened the red front door and in I went.

Oh she had it lovely, very nice, very comfortable with nice furniture. We had

tea and fancy cakes. Then we lit up our free issue cigarettes from Wills and sat

back in the comfortable armchairs.

Daisy said,

"Me and my husband Sam were what you call childhood sweethearts. When I was

fifteen years old, Sam and I knew one day we would marry. Now Sam was an

apprentice plumber, and I worked as an assistant in a drapers shop. So me and

Sam, started to save for the day we would marry. We courted steady until I was

twenty four and Sam was twenty

six. Then we married, we had saved enough money for a down deposit on this

house, a nice wedding and a weeks honeymoon at Bournemouth. So Nellie, we had

our wedding and went off to our honeymoon. While sat on the beach at

Bournemouth, Sam and I noticed a woman sat opposite us. A big fat woman with

very black hair with it curled and permed. On her face was thick make up. She

had crimson lips and thin black eyebrows. But what me and my Sam couldn't take

our eyes off was the jewels she wore. Thick gold hooped earings, a necklace

which was studded with diamonds, and on her fingers were gold rings with

precious stones. You could tell all the jewels were real. On her lap was a big

brown crocodile skin bag. As me and Sam watched her we wondered who she was, Sam

said, "Its obvious who she is, she's a Jew." I agreed with him because she had a

big nose. Nellie, I have never seen anything like it - there she was sat there,

with all her jewels sparkling in the sun. After a while Sam and I looked away,

and watched the children at play in the seawater. When we looked again at the

woman she had gone. But at the side of her deck chair was the crocodile skin

bag. Sam got up and walked over to the deck chair picked up the bag, came back

and sat in his deck chair, and put the bag on his lap. "Oh Sam," I said, that

woman has gone off without her bag, quick lets see if we can find her." Sam

said, "No, stay where you are, if she wants her bag she will come back for it."

So we both sat there not saying anything. After a while I said, "Sam lets open

the bag and see what's inside it." Sam said, "All right." He undone the big

clasp of the bag, and we both looked inside and my God Nellie the bag was full

of money, one pound notes and five pound notes. Sam shut the bag quickly.

Then we

looked at one another but didn't speak. Then I looked out at the sea. I don't

know how long we stayed there without speaking but I know it was a long time.

Then Sam turned to me and said, "What I want us to do now is to go back to the

boarding house. Pack our belongings, pay for our keep, then get the train back

to Bristol." I said, "Why Sam?" Now Sam was a very masterful man when he wanted

to be. He said, "Because I have said so." When we got home to Bristol to our

little house I made a cup of tea. As we sat drinking the tea Sam said, "Now

look, this is what we are going to do. This bag is going to be kept upstairs in

the tall boy. We shall live our lives as normal, but what we are going to do is

this. Every time we have to pay on this house, we will take the money from the

bag. But we will live the same as everybody else, we will not tell anyone about

the money as long as we live. "0 Sam", I said. You see Nelly I was so frightened

I felt as though we had stolen the money and I told Sam how I felt. Sam said, "0

no we haven't stolen the money, its ours." I said "We should take the bag with

the money in to the police." Sam said, "I bet we bloody well won't. What do you

think the police are going to do with the money? I don't know how she got that

money. All I know is its ours now and it can do us a lot of good."

So over the

years if we had a bill we would get the money from the bag to pay the bill.

There was two thousand pounds altogether in the brown crocodile skin bag. Every

year we would go on holiday but of course we wouldn't go to Bournemouth. We

didn't go out boozing or have a good time. We lived our lives like people like

us would. I had a son and as he grew up the money in the bag helped us no end.

It paid for a second hand piano for our son, and so the years went by. Our son

passed the eleven plus examination for grammar school, the money paid for his

uniform and extra books he needed. We didn't abuse the money. Over the years the

money saved us a lot of worry and stress. One day Sam said, "Daisy, we have come

to the end of the money in the bag. Now don't worry, because of that money I

have been able to save from my earnings enough money for our old age. But it

wasn't to be. Sam died suddenly from an heart attack. So Nellie, my Sam passed

away and I know he wouldn't mind me telling you about the bag, for lately it has

worried me, us having all that money which was not rightly ours."

My mother

looked at us three girls and said, "That was a true story, and do you know what.

Daisy went into hospital a few weeks later for an operation on her tummy and she

died during the operation." Then mother asked, "What would you three girls do if

you found a bag on the beach full with money." We answered with one voice -

"Keep it."

Pat Dallimore

WE SURVIVE

We survive from day to day

Our yesterday and tomorrow are the same

Hopes and desires like logs on a fire turn to ashes

No fire burn within

We are strangers in your land

Used and abused we cling to each other

Like lovers in each other

We find wells of contentment

A fire that smoulders and smoulders

Refusing to go out.

We survive from day to day

The future looks dim and uncertain

Without a solid foundation

Hopes and desires crumble

We will not be forever strangers

In your land

The scapegoat of your conscience

The under-nourished fire

That smoulder and smoulder

We survive from day to day

Past glories are nowhere recorded

No fire burns within

The hopes of tomorrow

Choked and erased by the prejudice of today?

The fire that smoulder and smoulder

Nowhere burst into a flame.

Steadfastly we hold to the belief

One day like the phoenix

The cold ashes will kindle a flame

That will warm the soul and set us free

Our yesterday will be a thing of the past

Never to be like our tomorrow

The glow of the fire within

Make of us all one people.

Keith Stephens

WHERE I COME FROM

I come from gullies

In the sister country

From coconut trees

And sugar canes

I come from the tree tops

In the jungle of pimentoes

From oranges, tangerines

And sour-sop fruits

I come from dusty roads

In gravel infested tracks

From mango-walks

And chocolate plantations

I come from shop fronts

Where salt fish is sold

From digging up yams

And planting corn

I come from JAMAICA

Where freedom is a taste

Where dancing to reggae

Is the sweetest thing on Earth.

LYNFORD SWEENEY

SKINDEEP

I am black

I don't need

To open

My mouth

To be

An

Offence.

Lynford Sweeney

NO FIXED ABODE

What can I do?

For I have no country to turn to.

Although I was born here

I feel as though I belong nowhere.

The English say,

"Black nigger,

Why don't you go back home?"

And I would if I could

But I have no home to go to.

My parents come from the West Indies,

But I can't go there,

Because I'm a British born black youth

And I don't belong nowhere.

My ancestors come from Africa,

And although I'd like to,

I can't go and settle down there

Because they'll say to me...

"You British born black youth,

You don't belong here."

So what can I do?

For I have no country to turn to.

Bev Shaw

SNOWDROP MAN

uncle john

who has

snowdrops

growing out

of his hair,

says:

spent whole

life

under

snowdrop

millionaires.

BLACKIE FORTUNA

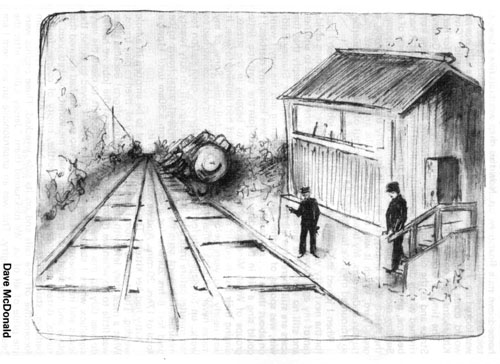

THE

GENERAL STRIKE

I left school

when 13 years of age to work in a pawn shop for 8/- per week. My job was to

obtain the keys from the local police shop in Belle Vue Street, now the British

Legion Club, dash to the shop for the manager to open up. There was always a big

queue on Monday mornings and woe betide me if we didn't open up at 7am. Pledges

such as suits, boots, costumes etc taken out at weekends for one day's sartorial

splendour were the first things to be 'popped' and cries of "Hurry up you little

so and so. He is waiting for his dinner money" were mild compared to some. It

was late in 1918, the Great War was soon to be over and industry was sacking men

and women left and right, and my few months at the pawn shop revealed to me the

many hardships and poverty unemployment brought. I had three sisters doing war

work on the Great Central Railway and my eldest sister got me a job on the

railway as I had reached the manly age of 14, celebrated by my mother buying me

a new suit, my first pair of long trousers. Talk about walk tall, as I escorted

my two other sisters to the Palace Theatre as a treat. They had both lost their

husbands, killed at the Dardanelles battle thanks to Churchill and his

blundering. So here I was working on a main line signal box for £1.00 for a 48

hour week as a train register boy. You entered all trains and times they passed

your section, and I loved every minute of it. The signalman to whom I was

attached was a bearded Tom Griffiths, a Methodist lay preacher and city

councillor who used to rant and rave about the injustices of the capitalist

system, and as I was with him for four years he had me at it - tub thumping.

Bear with me.

I am coming to the General Strike and what it did for me. By 1926, I had left

the signalbox, for at 20 years of age I became an adult and was made a station

porter for £1/15/- per week. I was on the late shift finishing at 11 .30pm and

at midnight the General Strike began. What worried me most was the station cat

who was about to have her umpteenth lot of kittens and as she was a real station

cat, the station was her castle and many a dog has fled yelping during her

pregnancies. Also four churns of milk had arrived from Rowsley on the last

train, a regular thing to happen but with Kitty locked up in the cosy and warm

porter's room, as I locked the station gates, I remember thinking Kitty and her

brood will be OK for milk. The pickets were already at the station entrance,

watching me lock up, and just as I made to get on my bike I was handed a picket

armband and told I would be relieved at 6am the following morning. I was there

when the horse-drawn milk float drew up. Now this chap was built like a tank. I

told him he couldn't get his milk as we were on strike and the station was

locked up. I was expecting the roof to fall in, but all he said was he would

come back and as he turned the horse around he said "Give Kitty some milk out of

the small churn" He always had a tit-bit for her.

The time, 5

o'clock in the morning of the first day of the General Strike and as the

clip-clop of the horses hooves and the rumbling iron rimmed wheels died away, I

suddenly realised how still and quiet it had become, no factory hooters,

clanging tramcars, it was the stillness of a Sunday morning a hundredfold. As I

walked wheeling my bike home, the streets were empty, no shops lit for early

trade, it was ghostly, a grave yard, which it was to become, of jobs and hopes,

dreams and human endeavours. My heavy tread seemed out of place in such silence,

so I mounted my bike for the rest of the way.

When I joined

the railway I was told I had a job for life, which I had for the next fifty

years. There was a large number of neighbours children of my age. How they

envied me my job as one year led to another and still no work. The General

Strike affected lives so deeply that the scars are still there after all these

years. (Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, was spoken of on the Tele the other

evening and the way I went on about the b . . . my family asked me if I was

losing my marbles.) I could sing a bit in those days and I used to join the

pathetic little groups of Welsh Miners who had to resort to begging in the

streets, singing their hearts out in neighbourhoods that had nothing to give. It

was nearly two years before I went back on full time. Some of my mates never got

back. When the strike was over this was how we had to work: on Sundays with few

trains running, sign on, open station for ten minutes before train due, ten

minutes later, sign off on duty twenty minutes. This went on until 11pm, when

finished, total hours to be paid for: 6 hrs 20mins. for a day lasting from

5.30am until 11pm, a total of 1 7hrs. 30 mins. And we were glad of it!

Kitty had her

kittens. The milk churns had to be emptied in a hole we dug. The students whom I

curse the memory of, tried to play trains. What a mess they left with their

strike breaking efforts! Because there was little to do when we returned to

work, one of the jobs we had to do was tidy up this mess and two of us were sent

to clean the very signalbox where I started my railway life. How I loved to

polish the levers and instruments, scrub and shine. Two students had manned this

place and the sight that greeted us made me vomit, buckets used as toilets,

dozens and dozens of beer bottles, empty of course, fouled bedding, stale and

rotting food, and a beautiful Atlantic type steam locomotive off the rails and

on its side, wrecked. These engines were the pride of all of us. We nicknamed

them "Jersey Lillies" after the beautiful Lilly Langtry. This was an

unpardonable sin and here I am living through it all again though half a century

ago. I don't know if my ramblings are anything like what you want but it has

done me good to hammer this out with one finger although I am getting dirty

looks from my family as my click-click-clicking is spoiling the TV programmes

for them.

MR B. J. HILL

WINNIE BE

DAMNED!

My grannie

Rosie was an ordinary Scottish working-class woman, of Irish extraction (her

maiden name was Bannon.) A Tim, then, but proud of it. She was not a

suffragette, nor a labour militant, in fact she liked playing whist, later

bingo, and she was known to fancy a glass of Bell's. She certainly had never

heard of Rosa Luxemburg, although she was good on her music-hall numbers, and

had been a bit of a classy dancer in her youth. Or at least, so they told me.

What she was good at was taking the piss. She had a deadly sense of humour, of a

subtle, sly type, which she could put over with the deadest of dead pans.

One day, when

I was a teenager, I went up to see her in her tenement house in Glen Street,

Tollcross, in Edinburgh. There was nobody in so I guessed that she would be

doing her messages at the Co-op. I let myself in with the key hanging behind the

door, hooking the string with a finger through the letter-box, and made myself a

cup of tea. After a while, I heard her slow trudge coming up the stairs,

frequently stopping, and accompanied by bouts of coughing. She was, she said,

short of breath. I knew that she had severe bronchitis, and that she wasn't

helping it with continuous smoking, but it was just that the stairs were killing

her these days, she would say. I opened the door, ran out, and took her heavy

bag of messages. She looked at me, her face collapsed, and putting her hands to

her face, she began to sob. Completely bewildered, I helped her into the house,

stuttering half-questions, half-reassuring noises. When she had taken a sip of

tea, she stopped sobbing long enough to tell me: "Oh son, Winnie's dead!"

My mind

flashed up-and-down the stair, checking-off the female neighbours: there was

Bella, there was Maggie, there was - there was definitely no Winnie. I couldn't

think at all who she was and quickly my mind started a radar-scan of the

complicated network of my Grannie's friends and neighbours in adjoining stairs.

I still couldn't place Winnie. Totally baffled, I took a gulp of tea, and

muttered:

"Oh that's

terrible."

My mind

re-started on pets, and I itemised all the neighbours' cats, dogs, and budgies.

No Winnie. So half-guiltily, I asked Rosie:

"Eh, I cannae think of who Winnie

is. Is it one of the neighbours?"

Rosie's sobs

ceased momentarily, and her hand came away from her face. Her eyes were

glistening, but it was not with tears of grief. She jumped to her feet and

started jigging round the kitchen table: "Winnie's deid, Winnie's deid, that

auld Tory bastard is deid, hurray-hurray!" I sat dumbfounded. Winnie. Winnie.

Winston bloody Churchill, by Jesus, and she had fooled me again. Rosie by this

time was doubled up with laughter, her eyes streaming tears of malicious delight

- both at the death of the enemy, and at having taken me to the cleaners -

again. Still cackling, she went to the press and produced her half-bottle of

Bell's. With much of "oh you should have seen your face", and "here son ah think

you need this", we sat roaring with laughter and drank a dram to the eternal

damnation of the man who put the tanks into Glasgow's meat market.

TO THE THIRTIES

'The wasted year' they have called you,

'A low, dishonest decade'.

Yet you were the year I grew up in,

The time my first contacts were made

With politics, poetry and people,

The age when I first was aware

Of a world beyond parents and classroom.

Dishonesty? Yes, it was there:-

Non-Intervention and Munich,

Celluloid Paradise Isles,

Bromide Beaverbrook headlines

And Senior Ministers' smiles.

This was all part of your picture –

A low decade! For all that,

Men could talk about struggles for Freedom

Without being considered 'Old Hat'.

With eyes nearly fifty years older

I look back. What hues do I see?

Inglorious Technicolour?

The grey tones of B.B.C.

No. The blood-red hues of Vienna

And the cities and valleys of Spain –

I still remember you, Thirties,

With passion, pride and pain.

Donald Bishop

STRIKE ONE!

St. Thomas's

School sounded like an overactive beehive on that Friday in August 1934. The

"weskit" tearing slum kids from Tipping Street had just been informed that they

were to go to Heaton Park on a camping, educational holiday.

Apart from

the bit of grass that was in Ardwick Green Park most of these kids, whose

fathers were on the 'cobba cole' P.A.C. or 'fiddling' for woodbines, and not in

the Halle! had never seen a bit of real country. Heaton Park could've been

Central Africa or the Amazon. But Monday was the big day. "Don't forget" the

sportsmaster told them, "A warm woollen jersey, a good pair of boots, a pair of

sports pumps and two pairs of clean underwear that can be worn as a football

strip."

The half

dozen lads who had been dubbed 'the school hooligans' 'toughs' 'Tipping Street

Bracer Swappers' 'ineducable' stood in a corner of the playground close to the

'lay's' where they could nip in and share a woodbine if one of them was lucky

enough to have one. They looked scruffy - clean but definitely scruffy, tattered

jerseys with frayed striped tie, holes in stockings, galoshes as they were

called, well worn - some with holes in. "What a right bunch" Mr. Bowens the

sports-master was heard to mutter, "They'll all end their days in Strangeways or

cornerboys." Cornerboys was the term given to the unemployed men who used to

stand on the corner of the street because they had nowhere else to go, searching

their pockets to make up enough for three cigs, and a match so they could share

a smoke and discuss their hopeless future.

"What bloody

chance have we got" said Stan one of the scruffs. "I don't even wear underwear,

me main can't afford it." Tiny, Dutch, Scrapper, Stick and Gunga Din the rest of

the gang all agreed, somewhat crestfallen.

The way these

lads got their nicknames was rather amusing. "Tiny" 'cos he was as big as a

house and the teachers were scared of him. "Dutch" his second name was Holland,

and "Scrapper" used to pinch lead off the rooves and takes it round to the

scrapyard for a few coppers. "Stick" cos his name was Cane, Gunga Dun, his

father worked for the Water Board. Stan had various nicknames "Cobba" "Lumpa" "Pieca"

and "Nutty Slack". These lads were all considered educational write offs, and

usually segregated in a corner at the back of the classroom.

They all,

however, expressed a keenness and determination to get to the camp and get the

necessary gear if they had to 'knock-off' all the lead on all the houses in

Ardwick.

Come Monday

morning they were all their with their little bundles of towel, soap, two vests,

two underpants, two pairs of socks, one pair of galoshes and the REAL PRIZE -

TWO HANDKERCHIEVES (Their cuffs would not be shiny for a while at least.

Their teacher

gave a look of despair when he saw them. "All right you lot, I want you at the

front of the bus where I can keep my eye on you, any trouble and you'll feel

this." He brandished a length of leather about eighteen inches long, about four

inches wide with six long slits down one end. They'd all felt its sting on many

occasions, so they were all aware of his threat.

"We've done

nowt." the six chorused. "Just in case you are thinking of mischief" he

retorted.

The journey

to Heaton Park went without the strap being used, there was only the noise of

excited chatter of kids from the slums who hadn't travelled so far, or seen such

greenery - they were all staring wide eyed out of the windows.

More

experienced hands had developed the camp site, and laid the bell tents. There

was a large marquee with tables and forms for eating, about six to a table, and

once you'd been allocated a table that's where you stayed, or got a "clip round

the lug hole."

As could be

expected the scruff were put together on the table nearest the flap where there

was most wind and teacher could keep his eye on them.

Mr Bowens was

overheard telling the camp organiser, another senior teacher, "Put that lot out

as far as possible, into the bush if possible." He laughed. "What a bleeding

great comedian, ought to be on the Hipp" commented Stan. Mr Bowens continued,

"They'll be less of a nuisance there, and if they make noises in the night

they'll not disturb the rest of us."

Tiny said

"I've a bloody good mind to go and disturb that bleeding comic now, not

tonight." "Leave it" said Scrapper "we might be able to knock off some grub,

we'll be better off with the 'toffee noses' out of the way." He could see there

wasn't much chance of a load of lead in Heaton Park.

For a few

days things went comparatively quietly, a few essays, a little drawing of

flowers, trees and birds - but there was a growing resentment from the Tipping

Street gang, they felt they were being isolated.

Gunga Din and

Stick were having a crafty 'woodbine' behind a bush, whilst the rest kept watch.

"He's laying

it on a bit thick lately" said Gunga Din. "The 'toffee noses' are all in a nice

cosy circle chatting about Nature and he sends us out here into the woods to

look at trees." "It's a wonder he didn't give us a banana each" laughed Stick,

grunting and scratching under his arms.

The expected

explosion came at tea-time on the Friday. The whole school of campers trooped

into the food marquee and took their places, chatting and grumbling about one

thing or another. At a sharp command from the senior master a whispering silence

was obtained, tea was slopped into mugs, stew was spooned onto plates, slices of

bread were issued, then the noisy rattle of eating continued for some time.

"Sir" was

going round with second chunks of bread in a basket, when he came to the

"scruffs" table. Stan said "Can I have another piece, Sir?" he queried.

Contemptuously the chunk of bread was flirted onto the table, it fell into a

pool of tea, slithered across the table and fell on the grass floor. "Pick it

up" said Sir. "Not on your bloody life" Stan replied. "You flung it, you pick it

up and scoff it." The miniature rebellion caused a repressive silence - it felt

like the tent was about to fall down.

"You'll do as

you're told" said Sir. "You can piss off" replied Stan. The Dictatorial attitude

of Sir, and the obvious contempt for the scruffs as had been indicated by the

throwing of the bread, whilst the 'toffee noses' had theirs politely placed

before them, had united the table behind Stan. "Think we're sodding animals

because we're poor" he shouted and started to walk out of the Marquee, the whole

table got up and followed his lead. "Come back here and take your seats at

once," Sir screamed. "Bollocks" was the unanimous chorus.

The Staff

were really confused by the united move of the scruffs the threat of "strap",

discipline - confined to tent - had all failed to bring them to heel.

The six lads

marched to their own tent and planned the next move, there was general agreement

that for some time they'd been unfairly treated, trying to make them eat bread

off the floor was the final insult.

"We can't go

back now" said Stan. "So what shall we do?" "Wait till it's dark and 'do' him"

replied Tiny angrily. "That'Il put us in the wrong" said Stan. "Let's piss off

home" burst out Stick. It seemed the best suggestion, so they all packed their

few belongings and started off. It was only when they got on the main road that

they all realised they had no food, no money, and not the foggiest idea which

way to go. By knocking on doors for drinks of water and 'butties' and asking

directions they were on the way. Fear was expressed about what the parents would

say - they might get a 'Belting' off the 'old fella' but at least they would not

be made to feel like something out of a cage.

It took them

all night and nearly all next day to reach their homes in Tipping Street, and

what a panic! The police had been searching for them, the parents were naturally

worried, some tearful, but all were glad to see the lads, there were millions of

questions, explanations, hot cups of tea and jam butties.

"There'd have

to be an enquiry after the holidays in front of the whole school" which there

was. Explanations again, Sir was slightly admonished, and was heard to say as he

was leaving the head masters office

"I DON'T KNOW

WHAT THE KIDS OF TODAY ARE COMING TO, OR WHAT THEY'LL TURN INTO."

Stan Cole

THE SUBBY

Subby with a seven one four

Trowel, spot and labrador

One thousand bricks to drop each day

Sod the irons, make it pay

Walls like Pisa, out of plumb,

Down the face the mortars run,

The cavity is full of shit,

Jerry built I've done my bit.

Three plank scaffold, no guardrail,

More than that at Walton Jail,

One false step, you're on the trap

Grasping Plunging through the gap.

Pouring rain, no guarantee,

Protective clothing, not for me

Rheumatic twinges, aching back,

Don't stop, shift that other stack.

The canteens filthy, minus sink,

Never swept, the wellies stink,

No heat, its a mucky digs,

Only fit for dirty pigs.

Death benefit, now what is that,

Gimmick of that Union brat,

Thinking of his wife again

The stupid dick has gone insane.

Holidays! what for I say?

I can't afford, I get no pay,

Free enterprise, this trails a kick,

I hope to christ I'm never sick.

Union men will show my lad,

The tricks, the trade, not too bad!

When of age He'll come with me,

Fully trained, and all for free.

If I'm alive at forty five,

On Union rate I will survive,

So think of me and up the rate,

I like my goodies on a plate.

Tom Walker

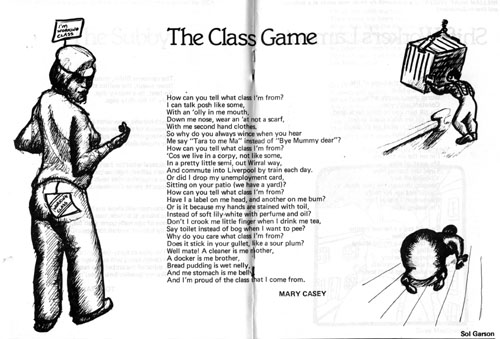

THE CLASS GAME

How can you tell what class I'm from?

I can talk posh like some,

With an 'oIly in me mouth,

Down me nose, wear an 'at not a scarf,

With me second hand clothes.

So why do you always wince when you hear

Me say "Tara to me Ma" instead of "Bye Mummy dear"?

How can you tell what class I'm from?

'Cos we live in a corpy, not like some,

In a pretty little semi, out Wirral way,

And commute into Liverpool by train each day.

Or did I drop my unemployment card,

Sitting on your patio (we have a yard)?

How can you tell what class I'm from?

Have I a label on me head, and another on me bum?

Or is it because my hands are stained with toil,

Instead of soft lily-white with perfume and oil?

Don't I crook me little finger when I drink me tea,

Say toilet instead of bog when I want to pee?

Why do you care what class I'm from?

Does it stick in your gullet, like a sour plum?

Well mate! A cleaner is me mother,

A docker is me brother,

Bread pudding is wet nelly,

And me stomach is me belly

And I'm proud of the class that I come from.

Mary Casey

SHIFT WORKERS LAMENT

Shift work is the curse of life

I'm feeling blue

Worse than a naggy wife

Constant with you

Six till two you're three parts dead

Two till ten life's spent in bed

Night shift is what we all dread

I'm feeling blue.

I'm on the six till two

My week of play

Tired and feeling blue

Yawning all day

Dancing through the club door

I could not ask for more

Remember, I rise at four

I'm feeling blue.

Two till ten's a hermit's game

I'm feeling blue

Life becomes a crying shame

Smiling is taboo

Enforced soberiety

And suitable propriety

For an outcast from society

I'm feeling blue.

I'm at war with the kids

They make my heart leap

When they bang the dustbin lids

As I try to sleep

Working while the stars burn bright

My poor stomach's in a plight

Through eating at the dead of night

I'm feeling blue.

On this bonny spinning orb

A dawn will surely break

When factory, machine and job

Are run for mankind's sake

Gone the sleepless nights we dread

The social patterns of the dead

The lustreless road that we have tread

Goodbye shift work blues.

WILLIAM HUNT VINCENT

ODE TO WINTER

Winter has arrived on site and turned in early

to catch us, trapped behind the yawning gate.

The change of wind has set our faces surly

against the wicked season workers hate.

The felt's blown off the cabin roof, the window's broken,

no fire to warm our boots and fingers by.

A cup of tea to stop the smokers choking,

then out into the world below the sky.

I waded yesterday through mud, now frozen dark and

jagged waves, the ice belies the depth of hidden ponds,

and on the walls where rain has dripped and hardened

hang icicles like summer's thickest fronds.

Here are men who summer like Olympian Greek gods

fallen to earth, victims of some elemental curse;

so now they scrape the hoar-frost from the handles of their hods

and pray the weather doesn't get much worse.

Yet in the midst of sorrow, cold and freezing,

there is still beyond the colours of the season,

reflected something I can find so pleasing

to echo Nature's dialectic reason.

White lime on bricks against the grey of mortar,

the scaffold that has browned to deeper rust,

a block of wood green in a pool's iced water,

and working hands as red as robin's breast.

Tea-time's still no nearer, and I'm sinking

more into my mood, pensive on the beauty and the pain;

but some-one bellows louder than I'm thinking;

"C'mon yer scabby get, gerrout the rain."

Arthur Adlen

THE LAST

SHIFT

It had been

raining on and off for the last two or three days. The -women of the village

were, as Mrs Evans from No 49 put it, "Fed up I am with this rain, can't get any

of my bedding out to dry, so near Xmas you see and so much to do." It was

Saturday morning and the wind blew the rain down the street at the, same time

nearly blowing out the three street lamps which did their best to light up the

village street at 4 o'clock in the morning.

Day Davis at

No 23 awoke with the sound of the rain and wind beating hard on the bedroom

window. He rolled over in bed, cuddling up closer to his wife, thinking to

himself it was far too early to get up as the alarm had not gone off: he would

try and go back to sleep again, which he did.

It seemed to

Day that five minutes later the alarm sent out its shrill ring to let Day know

it was 5 am, and time to get up and off to work. He put out his hand from the

bed and turned it off, and got settled down in the bed again. 'Another five

minutes and I'll be up' thought Day. His wife, however, was already up and

putting on a rather shabby dressing gown, drawing it up tight around herself as

if to keep out the rain and wind she could hear on the windows. It would be very

nice if it was Sunday so that Day and herself, Gwynn, could have a couple of

hours in bed. The thought passed through her head as she went down the stairs to

the kitchen cum living room to get Day his breakfast ready.

"Day, Day,

come along. It's quarter past five and you're going to be late for your shift"

Gwynn called softly from the bottom of the stairs. She did not want to wake the

kids up at this time of the morning. She waited at the bottom' of the stairs and

called again, "Day Davis, will you get out of that bed. You know very well you

have to get up and go to work." Gwynn heard the bed creak and also Day softly

swearing to himself. Gwynn smiled and went to see how the fire was in the

kitchen grate. Day was coming down the stairs still swearing to himself about

what a way to make a living, what a bloody morning it was with the rain and the

cold wind. Gwynn took no notice of Day. She had had this since she first got

married to him and that was over ten years ago. Mind you, his mother had

forewarned her, but coming from a family of five brothers and her the only

daughter and the youngest, she was quite used to men and their ways. It was no

good being otherwise, being married to a miner and sister to five more.

Day washed

his hands and face in the back kitchen, dried himself on the spotlessly clean

towel, combed his fine head of hair and went and sat down in the kitchen with

his back to the fire and had his breakfast. Breakfast in the late 1920's in any

mining village in South Wales did not run to eggs, bacon and so forth: no,

indeed not.

Day sat down

to hot toast and dripping and a pint of hot tea made with condensed milk to

sweeten it. His wages did not go as far as having a good breakfast every morning

before going down the mine for ten hours or more each day.

Day finished

his breakfast and lit a woodbine, enjoying the warmth of the fire on his back.

Gwynn had already put his Jack Box and his bottle of tea and also two more

woodbines on the table. He smoked one going to work and the other coming home.

After his smoke he put on his big, heavy boots. Gwynn handed him his coat, scarf

and cap which she had been warming for him in front of the fire. Day nodded his

thanks to her. It was enough for Gwynn. Day was stood near the door ready to go

to work when he said to Gwynn, "You have forgotten Blodwynn this morning, girl.

She will be very cross, you see, if I don't take her a couple of apples. I can't

have her being upset all the day can I now, see girl". Gwynn went back into the

kitchen and returned with two very large apples saying to Day, "At times, Boyoo,

I think you care more about that damn ol' pit pony than what you think of me.

Blodwynn must have her apples every day. Can't upset Blodwynn. I wonder how many

other miners take apples and a bit of cake for the pit pony?" Even as she made

this statement, she remembered her mother and her five brothers, her mother

leaving extra food near their Jack boxes, cake, home made bread, apples, at the

same time saying to her sons, "It takes me all the time to feed you lot without

your silly old ponies.

I'll have to

take more money off you if I'm expected to feed those animals as well." The five

sons would stand and laugh at her saying "Hello our Main's at it again over the

pit ponies." Gwynn walked to the door and stood near Day. The rain had stopped

but it was still very windy and cold. Day put his arms round Gwynn and held her

close to him as if he was going to tell her something, but changed his mind, and

let her go saying he would be home in the afternoon to have his bath in front of

the fire, then take the two children to his mother's house for an hour as he did

every Saturday.

She watched

him join some other miners who greeted him with "It's a bloody cold one this

morning. Wish I'd stopped in bed with the wife instead of walking to work like a

bloody silly fool." Someone at the back of the crowd shouted. "You may as well

go to work Harry, you know you're getting past that sort of thing these days. I

should leave it to the new Tally man. They do say he's a rum un with the women

and he's due on Saturday mornings." This statement brought forth a burst of

laughter and other remarks about Harry's sex life. Even Harry had to laugh.

While Gwynn stood at the doorway watching the men go to work, one miner shouted

out to her, "Morning Gwynn, you alright girl?" She looked up and saw it was one

of her three brothers all working the same shift as Dav. The other two went on

work as soon as these three came off. Each brother called to her a kind,

brotherly remark, asking how was our Gwynn and the kids this morning? Had she

managed to get Day out of bed on a cold morning like it was? See you Sunday at

chapel, girl.

Day walked

down the street with the other miners, only half listening to the talk on

football, who should win, who should score. He had meant to say something to

Gwynn, something that had been on his mind for a very long time now. The trouble

was he did not know just how to tell her. How would she take it? This thought he

had had some time ago seemed at the time so silly and impossible. The more his

mind thought about it with all the ifs and buts; the what about this and the

what about that? What will people say? Are you sure you're doing the right

thing? .

Day had never

liked the idea of spending the rest of his life working down the pits. To his

way of thinking, the idea of son following father down the pits was wrong. Even

in the late 1920's there must be other ways of making a living without going to

work in the dark. After all, not everyone worked in the pits. There must be

other ways to make a living, even working on the land in the fresh air. Day was

cutting coal on the face one day when this idea came to him. Emigrate to New

Zealand, Canada. Why not? Others had done it from what he had read in the

papers.

He had read

the papers about men working in the large forest part of Canada, cutting down

and trimming the huge trees ready for the paper mills, it would be hard work and

long hours, but he was quite used to hard work and long hours. Day had been

thinking along these lines for a few weeks now. There had been many times he had

sat after a meal looking into the fire as if the answer to his thoughts was

there. Gwynn, his wife, she had many a time had to say to him when he was

looking into the fire "C'mon Boyoo, come back, you seem to be many miles away.

I've spoken to you twice but you didn't answer me."

By the time

Day 'had got to work at the pit head, he had made up his mind to have a good

talk to Gwynn over the weekend, explain to her what was on his mind, listen to

all her ifs and buts - which, knowing her as he did there would be plenty of.

Day, while at the pit head with the other miners, turned out his pockets for the

odd match, each miner doing the same and trusting each other never to take the

odd couple of matches down the pit to have a quick smoke. A lot of the older

miners knew that a quick smoke down the pit had many a time cost lives. When the

cradle had stopped at the pit bottom, Day and the other miners walked the half

mile or so to their place of work. They walked in twos and threes, breaking away

from the main group and going to their own places of work in the pit. Day along

with Ted, his wife's younger brother, after ducking their heads and at times

almost bent double, got to the coalface and made ready to start the last shift

before the Xmas holiday.

Both Day and

Ted worked on at a steady pace. They worked with each other as a team, each one

knowing he could depend on the other man no matter how hard work was. Now and

again Ted would burst forth into song while he was working. He had quite a good

voice and at times he would sing on a Sunday night in chapel. It had been a

standing joke when one day Day had said on being asked what he thought about

Ted's voice, "Ted's singing? Why man, Ted's got a voice like a bird, a bloody

minerbird." Sometimes while Ted was singing in chapel on a Sunday night, Day

would try to get him to look at him. If Ted did look at him, Day would raise his

elbows up and down like a bird in flight. Ted would turn his head away to stop

himself laughing.

It was well

after snap time and the two were at work again. Day had given Blodwynn her two

apples and some of Ted's food. Day had said to Ted that he was putting on too

much weight so he should give some of his snap to the pit pony.

They both

heard the far away muffled sound of the explosion. They stopped working and

looked at each other. Ted said "They must be blasting at the far end, you know

where I mean Day, the North end." Everyone had stopped working. The mine was

very still. "Funney" said Day, "No-one has been along to forewarn us about any

blastings in this shift. We should be told about these things at the start of

the shift, not half way through it."

The second

explosion seemed nearer and louder. "I don't like it. C'mon, Ted, let's go and

find out what the bloody hell is going on down there."

They were

making their way along the narrow passage that lead to the main tunnel when the

third and fourth explosions came. For an instant Day looked back. To him it

looked as if a powerful pair of hands had pushed the whole of the coal face

forward in very large lumps of coal, rock, bits of wooden beams: the explosion

with its overpowering colour scheme reminded Day of the time he had spent in

France in the War years. When he had first gone to the front he had been amazed

at the colours of the big shells as they exploded. He had soon learned to duck

his head as the shells came over. He felt himself being lifted up. He felt the

blast of very hot air. It seemed to burn into his half naked body. He heard a

scream, heard his name being shouted. He felt as if his body was being picked up

and thrown from one side of the pit wall to the other, picked up again and

thrown against the walls, and again. Day's body, not being able to take any more

of this uncontrollable power, hit the floor for the last time. He fell to the

floor of the pit badly burnt and broken. At the same time his mind quickly

slipped into a blessing of blackness.

It was 10.30

am when the alarm hooter at the top of the pithead sent out its fearful call to

the village below. Everyone in the village just stood still as though unable to

move. Some of the people of the village had heard the sound many years ago when

the old queen was alive and it brought back many bitter thoughts. Everyone

seemed to be running to the pithead at the same time, the women putting on their

shawls, the men their caps and coats. Dr Jenkins was busy along with his wife

putting medical items into his old Austin Seven.

Soon the pit

yard was full of people all wanting to know what had happened. The pit manager

was stood on a box outside his office trying to get a bit of order. He could

tell them very little at present: Dr Jenkins and a rescue team had gone down so

they would have to wait until one of the rescue party returned to inform them.

They waited and waited and at the same time hoping that it was not their man who

might be hurt or dead. "Let's hope its not my man or my sons". You could see

this in the eyes and on the faces of the people who waited and hoped.

The wheels of

the pit turned and the cage drew level with the yard. Two of the rescue party

stepped out and walked across to the pit manager's office. He came out and stood

on the box with a piece of paper in his hand and started to read from it. The

pit foreman had sent up the note stating that there had been three small

explosions and one very big one. It was this last one that had done the damage

and the injuries. He went on to say that there were still 47 men missing and

here were their names . . . . Ted Evans, Day Davis . . . . Gwynn stood and

swayed while Mrs Evans held onto her.

The old army

lorry pulled into the pit yard and stopped. A young man who was a doctor, and

two nurses wearing spotless white dresses with a large red cross on the front

jumped down from the front seat and went into the office. From the rear of the

lorry men were jumping down, some were dressed in their best suits, some were

dressed as if they themselves had just come from a pit, wearing their helmets

and pit clothes. The doctor and nurses came out of the office and with the men

from the lorry carrying rescue equipment all walked to the pit cage.

The people of

the village still waited. The cage was going up and down more often now, as if

the rescue parties were finding more of the missing miners. Each time the cage

came up, the pit manager would look at its ghastly load and call across the

yard, "Jack Lewis, dead. Ron Ford, dead. Tim Jones, badly injured " and so

the roll call went on. By 10pm the crowd had thinned out. The list of missing

men had been cut down to nine. There was no point in waiting when after a name

was stated came the word 'dead'. Some of the women followed their dead men-folk

to the school some went home; others just stood there not knowing what to do.

They were stunned by it all. It had to be a bad nightmare. It had to be

It was 1.30am

and the wheels were turning again. The pit manager called out the names. The

list was cut down to the missing four. Gwynn and her mother still waited. One of

her brothers suggested that they go home for a while and have a hot meal and a

drink. The two took no notice.

At 2am the

wheels turned again but this time it was the two nurses along with some of the

rescue party. Gone were the spotless white uniforms with their bright red

crosses. The nurses were covered from head to foot in coal dirt. The uniforms

were torn. Their shoes were broken. Their fancy little hats had gone, exposing

their hair, full of dust and dirt from the pit where they had spent so many

hours.

The doctors,

nurses and some of the rescue party went into the manager's office, closing the

door as they went in. The people could see them stood talking and looking grim

by the lights that had been set up in the yard. They saw the pit manager and the

rescue party looking at pit maps on the table. After a while, the manager came

out of his office and asked the small group of people if they would go into his

office as he had something to tell them. " and I am sorry to say that

there's nothing more that anyone can do. The gas is coming in so fast that it

has already passed the place where the last miner was found. As for the four

missing men, they must be further along the pit. I should think by now that they

must be dead, I'm very sorry to say. He spoke to the doctors, nurses and rescue

party. He thanked them for all their help in their hour of need, adding it was

pointless to try and do any more. Everything had been done that could have been

done.

Day Davis lay

in the pitch blackness, his body broken and badly burnt. The only sound was

himself fighting for his breath, turning his head this way and that trying not

to breathe the gas that was filling the small space. He thought of Gwynn, his

wife. He thought of his two children. His mind was thinking of all sorts of

things, things he had never given a thought to for years. It was getting harder

to breathe. The small space was filling up. There was very little air left now.

Gwynn. The kids. Gwynn, Gwynn . . . . He lay there thinking of Gwynn, the kids

and himself. What would it have been like in Canada? He lay there, knowing he

would be doing what he never wanted to do and that was to spend the rest of his

life in the pit

Victor Irving

FACTORY FLOOR POEM NO.2

The floor creep truckled to the charge

for the gen: annual bonus; canteen; 1/4 hour.

Scabs scurried first; then, the union faithful.

Red buttons halted jostling tins

on spirals overhead.

Their subsidised meal well nudged down

couples stood about –

enrolled into shop faction by rival rankings.

The manager signalled with his memo pad

"all hands assembled".

Mr. Arnold Stubbs hawked the financial year.

A cough like a pub comic's curtain raiser

greeted him.

Arnold Stubbs was a natural conserver,

mostly of his own talents.

"Overtime payments have severely taxed

liquidity," he began,

production has fallen off . . .

The assembly closed up to shoulder

his shafts as he higgled away

at their silent "how much?"

"Twelve pounds cash each," he'd said.

"Twelve pounds! For a year's work."

Victor Magor

WHEN THE SOLDIERS CAME

When the soldiers came

Wasn't I in the bath with no clothes on,

Wasn't I just getting out when someone

Handed me the towel and there was

Six grinning Brits at all me attractions

And me just seventeen never been kissed

Except by me Ma and Da and Billy Mullen

Once at the bus stop outside Donnely's

Wasn't I that shocked I dropped

the towel and hid myself behind the door?

They laughed and left me there, didn't

I hear them clattering in all the house,

Throwing down drawers, beds, books, letters,

Lives, didn't I?

None of us were beaten, none taken away,

Yet, huddled behind the door, wasn't I

Something beaten, something taken away, forever?

Joe Smythe

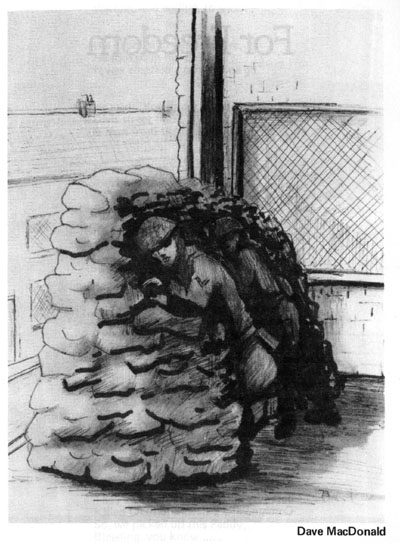

BOMB DISPOSAL

I watched you

the other night

on the Tele

- Frightened

uncomprehending

huddles of boy soldiers

with raw scrubbed necks

and ashen cheeks

- determined

anxious expressions

across the faces

of officers

I watched you

crammed into doorways

or prostrate behind sandbags

as the experts from the squad

attempted by robot

to defuse it.

I read in your faces

the fear

the unknowing

saw

the look of men

with so many questions unanswered

that they no longer ask why.

Robert Emmet warned you

but you hanged him

James Connolly told you what would happen

but you shot him

A million and a half peasants screamed out to you

but you let them starve.

So still you cannot see

that sooner or later

it's going to explode

in your faces.

Phil Boyd

FOR FREEDOM

'You're first on the list',

Said my S.A.S. friend,

As he nodded to the left.

'We'll be knocking up you

In the dark of the night',

Smiling at one of the guests.

The party was noisy,

We stood in a corner,

Drinking and talking away.

'I learnt it in Ireland,

To spy on my friends,

It's a gamble I have to take.'

'All that shit about freedom,

And brotherly love;

It's a joke to me, and my mates.'

He knocked back his whisky,

Then went for another,

Smacking a girl on the rump.

'We've a list for your lot,

Just for round here.

Commies and Lefties and that.

We're all over the place,

In civvies or out,

Waiting, and willing, to shoot'.

His expression grew sombre,

He looked in his glass,

It was emptied again, in one go.

He said, 'You know Ireland?

Divis street flats? Shot

A man from the roof there one night.

He was just going home,

But I felt like some fun,

So he died on the pavement below'.

He refilled his glass,

Twirled it round in one hand,

Downing it with a grin.

Wiping his lips, a drink in his hands,

He turned round to me, yet again.

'Those U2 batteries you use in a torch,

You can use them as bullets, you know'.

He paused, and then said,

No trace of a smile,

'I'll be glad when you fuckers are dead.

It ain't nothing personal,

To me it's my job,

like One day in Belfast,

They ambushed my mates.

Killed Charlie, shot in the head.

So, we picked up this Paddy,

Bleeding, you know

And lay him down in the truck.

And we said,

"All right mate, we'll get you out,

Just hang on a while till we go'.

But we didn't you know,

We just left him to die,

God, the blood in the back of that truck'.

I left after that, He lay slumped in a chair.

His glass tilted down to the floor.

As the lift took me down,

I recalled in Malaya,

How the bodies of S.A.S. soldiers lay there.

Forgotten by most,

Recalled by a few.

And as one of these said,

A hard bitten bastard, he was,

'For what? For nobody

Cares,

Now, at all'.

R Carpenter

THE

PSYCHIATRIC UNIT

George Owens

looked at the polystyrene dragon one more time. It was hideous. And in this

effigy was proclaimed the whole sum fears of all the patients that had passed

through this establishment and the intended serenity of its walls. Iron bars,

iron cots, hot water pipes and iron radiators. A nurse watching to see you

hadn't stole a patient's razor, or was hanging yourself with the wet towels in

the shower.

After 3 weeks

here, the causes of George's compulsive sleeping were still unidentified. But he

sensed that he was constantly being watched as he squeezed his blackheads out in

their mirrors. They were too blatant, no amount of tranquilisers could keep

their note-making and spying from him.

All life here

was the same game of chess with the same missing pieces, the same afternoon that

had lasted three weeks now. You just kept going back to it and people got fed up

with it, and you'd find other people to play it with, and it wasn't the people

it was the pieces, cos you never played to win and they were too drugged to

recognise or they were making allowances. Or they were taking notes.

One man here

had gone crazy, like a rowing boat on an ocean, after he'd left prison. They

said that he would do anything to go back to a nice warm cell. Another had

merely gone "nuts-whole-hazel-nuts" on valium and alcohol. A boy of 19 had drank

weed-killer after his girlfriend had aborted their child.

Three

evenings a week there would be a whist drive with the women from Psychiatric 1.

Unmarried mothers, battered wives, teenage girls. One fat spinster in a

wheel-chair was legless from her suicide bid on the Birkenhead subway. She was

there. An evening of this was enough to drive the sane to escape. But known

escapists were given a syrup which caused vomiting on contact with alcohol. So,

30 minutes later, Joe's Bar would be on the phone, and the ambulance sent out.

They'd be spending the next two days in the freezer, then a week in pyjamas

without privileges.

After the tea

break George was led to the art room by an older O.T. lady who didn't try

anything. They walked down the fire escape, well armed with her bunch of keys.

She spoke to George as if he were all of 26 and had just been on a visit to the

school dentist. They watched a masked man spray the underside of a hoisted

ambulance. It was occupation day and the O.T. lady asked George if this was a

job he would like to do: to steam-spray the underside of an angel of mercy,

capable of doing 120 mph on open motorway, but held a torturing 6 ft from the

ground, caressed by the man in blue overalls. She asked George if he would like

to stand and watch, but left it at that. Clean clinic cream. Half empty milk

bottles turned green. Was she taking notes? Was she waiting for him to comment?

Would she mark in her notebook when he tried to change the subject. . . What?

Inside the

art room was a young woman modelling pottery. She wore an overall and had her

hair poneytailed in an elastic band to avoid the flying mud from the clay

abortion. Distractions, that’s all the world played on. Why did everything in

here play-up sexual? When were they taking notes and when were they blind

When?

You could

withdraw and say absolutely nothing to no-one ever again. But they'd use more

drugs to loosen your tongue. If you went even quieter they'd use more drugs, and

you'd never get out, never, ever. Or you'd say something dirty and they'd give

you Electric Convulsive. That's it, they were just waiting for you to say

something dirty.

"Now draw a

picture." "Oh, anything. The first thing that comes into your head." (What does

every guy look at first?). George held the dreaded pencil which committed him to

doom. A still life, that'd fool them. No, they'd analyse the shapes, the curves

would give you away. Draw something, anything. Quick, she's watching you

hesitate, she's writing out the form for more drugs. I know "I don't feel

like drawing anything today, I've got no ideas in my head."

John Gowling

BREAK FOR A COMMERCIAL

Break for a commercial,

They tell you "beer is best"

What to do on your holiday,

what to do with your money.

How to gain in confidence

how to grow in stature.

Break for a commercial,

They tell you "bread is good",

Once it was "A bank manager in your cupboard"

Today it puts "the umbrella of insurance over your family".

Break for a commercial,

They tell you how "to shop in style".

This is "Your life"

This is "Opportunity knocking"

This is the culture of "Coronation Street".

This is the intruder in your home.

Today you Pay, they profit.

Today you buy, they sell

Today you ''want

They provide

Break for a commercial,

Hear the cash register jingle.

Crispin

CHILD WATCHING

If they ask us why we kept silent say

We did it for the children. Certainly

We knew about the locked wagons, the night

Visits, the panicked scream, the bruised faces.

It wasn't right, but you don't muck up

Your career for some black Mick McJew.

When we saw the small fist of protest, I

Whispered that they had a point. You

Agreed. Only for the children we might

Have joined, risked going on file, risked

Mockery, risked the commitment that the

Poor must give; total. No way back.

When we joined the celebrations we did

It for the children. We bought balloons,

Candy-floss, tossed skittles, guessed the

Weight of the pig, had a go at the hoopla.

We listened to the band and at the end remarked

The soldiers looked smart with their stub guns.

Round, dark eyes follow me inside

And out. I wish they'd go away.

Joe Sheerin

THE GOOD OLD ENGLISH BOBBY

It was a hot

summer day in August 74. Hundreds of men and women were gathering into a march.

They were marching to picket a factory in Tower Bridge in support of fellow

workers. There were people organising the marchers into an organised column. My

job was to see that reporters didn't talk to people in a way that may trick them

into saying things to put a bad look on the march. In the past reporters have

got marchers unknowingly to say something detrimental against the object of the

march.

The march

started to the factory, people laughing, singing and shouting. The sun was