|

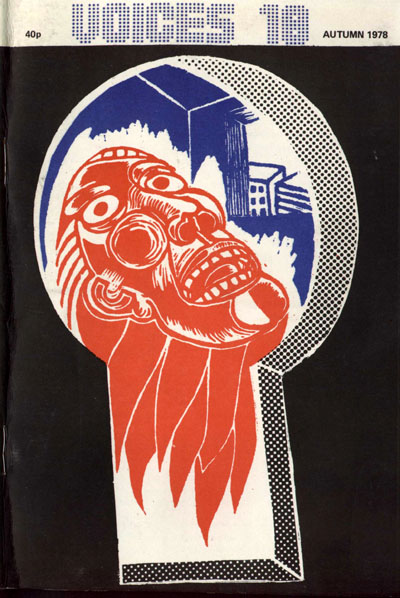

ISSUE 18

cover size 210 x 148 mm (A5)

Editorial . Rick Gwilt

Captive Audience Bill Eburn

"Culture" Sated Freaks Bob Cooney

Date With Royalty Jack Rhyland

For Humanity's Sake Bert Ward

Saturday Night in the Higson's John Small

Advice from a Big Industrialist to a Worker Betty Baer

What've you got in your Briefcase, Mister? Keith Armstrong

News Item Alan C. Brown

Song of Warning for William Morris Ken Worpole

The First Million Pound Pools Winner Roger Mills

Lord Street Revisited Pete Farrow

Richman, Poorman, Beggarman W. Lloyd Thomas

A Start in Life Bob Drysdale

Jobs For All Bill Eburn

Letter From Father to Daughter Linda Weller

Why Do I Steal Cars? John Gowling

Blubber Donald Whitmore

The Concrete Ground Claire Mooney

The Man on the Hoss at Durham D. Beavis

I Will Not Remember You When You're Dead Joe Smythe

Poem to Kieran Nugent Phil Boyd

Me Medals Stan Cole

Who are the English? Jim Ward

Jersey Holiday Pat Arrowsmith

The Rise and Fail of the English Pub Ripyard Cuddling

A Day in the Park Dave Barnes

Sleeping Dogs Rick Gwilt

One Voice, Many Voices Val McKenzie

Point of View Joy Matthews

Poverty Skills Frances Moore

Four Letter Words Frances Moore

Principles of Art Bill Eburn

Voices Bill Eburn

Poet Bill Eburn

Voices Ron Perry

In VOICES 16 I wrote that in the short term "we aim to

provide a link between worker-writers and the organised trade union movement. In

the slightly longer term, by also developing links through Unity of Arts with

people in other branches of the arts, perhaps we can help to re-open discussion

on Resolution 42 within the labour movement."

The long-term perspective is looking less and less

realistic, not least because "Unity of Arts" survives only as the name on

VOICES' bank account. Since "Unity of Arts" was founded there has been a

tremendous upsurge in what has come to be known as "community arts", especially

in the fields of theatre and creative writing, where so many diverse and

autonomous groups have sprung up. Federations to which such groups can affiliate

without losing their autonomy ("WorkerWriters and Community Publishers" is a

good example) seem more appropriate. NW Spanner Theatre Group, in organising a

campaign against political censorship, found that this incredible hulk of a job

nearly split their costumes. So VOICES would do well to concentrate on its

short-term aims.

VOICES has long since been a national publication, more by

force of circumstances than by design), and our obvious base of support is WWCP.

The appointment of a full-time co-ordinator for WWCP (financed jointly by the

Arts Council and Gulbenkian) coincides with VOICES feeling the need for some

kind of full-time worker more than ever before. Ben Ainley was retired when he

founded VOICES and I was taking a breather on a university course when I first

took over. Given that working-class writers and artists tend to be a bit

backward in coming forward, much more time needs spending on soliciting

material, including the as-yet-unwritten. The content of the magazine does not

seem to be suffering too badly, but regularity of publication and feedback to

contributors certainly are.

So we are trying to improve this situation in two ways.

Firstly, member groups of the WWCP Federation have accepted greater

responsibility for collecting material for VOICES, as well as selling copies of

the magazine in their own areas. Secondly, we are trying to raise The money for

a full-time editor-something which will no doubt be of greater interest to the

many scattered contributors working in isolation and waiting patiently for

replies from an overworked editor.

October 1978

Rick Gwilt

CAPTIVE AUDIENCE

"Do you really

have to go all that way

to hear some git

read his poetry ?"

"I do" said I.

"But why ?" asked she.

"Because that git

happens to be me”

Bill Eburn

'CULTURE' SATED FREAKS

See the "culture"-sated freaks

Crimson shirts and moleskin creeks

Garb and manner both devised

that shallowness might be disguised

as "character"-a shameless fraud-

concocted that we might applaud

Believing what's not understood

Must therefore be EXTREMELY good.

Bob Cooney

DATE WITH ROYALTY

The beaters advance

With their hazel sticks,

Tossing havoc through the briars.

"Hulloss! Hulloss! Yo! Yo!"

Gun dogs, tongues lathered,

Spurt down the rides.

This is the moment he was nourished for.

Now, in mid-air, Cock Pheasant

Appears before the Duke

Jack Rhyland

FOR HUMANITY’S SAKE

Be caring

For those

Who go into this world

Fearful and insecure

Unprotected

Against the cold note

Of a friend’s back turned

The white ice

That glitters the eyes

The glancing frost

That pierces the blood

Chills the limbs

And hardens the heart

For future encounters

Bert Ward

SATURDAY NIGHT IN THE HIGSONS

The night Albert fell at the bar-room door people walked

past him. Mrs Jones who is sixty seven and pisses down her legs said he was

bevvied. Then she sat down again with her mates and had another glass of lager.

Most of the people in the bar were in a bad mood. Cowboy Joe Dean who is the

South End's answer to Johnny Cash was playing his Country and Western songs.

When he plays the television goes off and everyone has to talk to one another.

The worst thing about his singing is his timing. Not the timing of the rhythm of

the songs, but the time he plays them. He sings "Ring of Fire" at half-past

nine. You don't have to look up at the clock. "Country Roads" is sung at

ten-to-ten. It goes on like that all night. People order ale on the strength of

his timing.

As Joe sings Albert moves round the bar. Albert is an

alcoholic. He is dirty and smells of stale sweat. For a few glasses of beer each

night he picks up empties off the tables. This suits Albert, it gives him a

chance to do a bit of minesweeping. That's drinking anyone's ale who has their

backs turned. It was late when he fell over by the door. Everyone in the bar

paid no attention to him till this fella coming in fell over him. Then Billy Mac

said, "Throw him out. He's drunk."

Steve, who is a mate of mine, works in the hospital as a

porter. When Albert fell over Steve was selling Spot-the-Ball tickets in the

back-room. One of Mrs. Jones' mates came over to look at Albert and said he'd

conked out but she could help. Then she pulled a bottle of pills from her bag

and put one in Albert's mouth.

"That will fix him", she said, to the other old girls

sitting watching. "Them tablets don't half work good".

That's when Steve came back in the bar. Right away he knew

what was wrong with Albert.

"He's had a heart attack", he shouted, kneeling over

the body. "Call an ambulance someone".

He hit Albert on the chest and blew down his mouth holding

Albert's nose. Then he pulled his head back and poked his fingers in Albert's

mouth. He had the tablet in his fingers.

"I gave him that" the old one said. "I've got a bad heart

meself".

A big circle had formed round Steve. Most of them were

watching in silence with pints in their hand. Steve was frantic trying to pump

air into Albert and bang his chest, at the same time trying to find out what the

old woman had given Albert.

"It was TNT tablets", she said at last.

It seemed ages before anything happened. Someone at the

back of the crowd said

"Ah Steve's dead good at that, don't you think". The fella next to him said,

"Yea, next time I have a heart attack I'll call him".

The sound of the ambulance was heard as it came up the

street. It stopped outside the pub and two attendants got out, came in and

picked Albert up on a stretcher. Steve went with them in the back with Albert.

We all walked back into the pub and Cowboy Joe started to play again. He did

miss three numbers out but kept to his normal time. It was then that this fella

came up to me and said:

"Ah, your mate's a bit of a hero isn't he, ah".

I said "You think so, ah ?"

"Dead right he is. I've got the winning ticket and he's

pissed off with the money".

John Small

ADVICE FROM A BIG INDUSTRIALIST TO A WORKER

Now, lad, you improve

Your productivity

and we'll rub off

all your corners

and knock you into shape

till you become

a lovely ball-bearing

(minimum oil)

in the hub

of a huge, faceless machine

pumping out

oodles for ooz.

Betty Baer

WHAT'VE YOU GOT IN YOUR BRIEFCASE, MISTER?

What have you got in your brief-case mister

a room with a view at the Ritz?

What have you got in your brief-case mister

plans for a bomb or a blitz ?

We know there's no room in the boardroom mister

for some one who's black from the pits

No we know there's no run on a royal ship mister

for sailors who've been blown to bits.

And you know there's no risk at a court-case mister

for those who are guilty but rich

No excuse at all for a woman mister

to choose her own way to resist

And know there's no place on a Concorde Minister

for babies not born on the list

No place at the Palace for coloureds

Minister for races and faces to mix

So what have you got in your brief-case mister

a room with a view at the Ritz?

What have you got in your brief-case mister

plans for a bomb or a blitz ?

Keith Armstrong

NEWS ITEM

The young man who mended Princess Margaret's smile

Has been told by the Queen to BUZZ OFF!

That might spoil his chance of a Golden Disc, yet he'll

Continue to RING her and think about it

At least he says for a while.

They holiday'd together and took the sun

(We wondered (up North) who'd removed it from OUR sky)

The world may love a lover; but if a Princess has ONE

The world and Mrs. Grundy can't turn a blind EYE.

Ah ! no. The Beatles were wrong apart from LOVE you need

A lot of money-to holiday on.

Now the Press can turn a fine phrase-but abhors a lie

(Even if it's a rich ermine-gowned one !)

A ROYAL lie ? Never! It can't be done:

Whoever heard of the like

not you, certainly, what's more

not I!

What will happen next? Where will he go- Siberia perhaps or the Nile?

That sad young man who once (long ago)

mended Princess Margaret's smile.

Alan C Brown

SONG OF WARNING FOR WILLIAM MORRIS

WHAT'VE YOU GOT IN YOUR BRIEFCASE, MISTER?

What have you got in your brief-case mister

a room with a view at the Ritz?

What have you got in your brief-case mister

plans for a bomb or a blitz ?

We know there's no room in the boardroom mister

for some one who's black from the pits

No we know there's no run on a royal ship mister

for sailors who've been blown to bits.

And you know there's no risk at a court-case mister

for those who are guilty but rich

No excuse at all for a woman mister

to choose her own way to resist

And know there's no place on a Concorde Minister

for babies not born on the list

No place at the Palace for coloureds

Minister for races and faces to mix

So what have you got in your brief-case mister

a room with a view at the Ritz?

What have you got in your brief-case mister

plans for a bomb or a blitz ?

Keith Armstrong

NEWS ITEM

The young man who mended Princess Margaret's smile

Has been told by the Queen to BUZZ OFF!

That might spoil his chance of a Golden Disc, yet he'll

Continue to RING her and think about it

At least he says for a while.

They holiday'd together and took the sun

(We wondered (up North) who'd removed it from OUR sky)

The world may love a lover; but if a Princess has ONE

The world and Mrs. Grundy can't turn a blind EYE.

Ah ! no. The Beatles were wrong apart from LOVE you need

A lot of money-to holiday on.

Now the Press can turn a fine phrase-but abhors a lie

(Even if it's a rich ermine-gowned one !)

A ROYAL lie ? Never! It can't be done:

Whoever heard of the like

not you, certainly, what's more

not I!

What will happen next? Where will he go- Siberia perhaps or the Nile?

That sad young man who once (long ago)

mended Princess Margaret's smile.

Alan C Brown

SONG OF WARNING FOR WILLIAM MORRIS

'The Special Branch visited Oakdale Community College, South Wales,

to investigate a course teaching William Morris, Karl Marx, and

other 19th century writers.'

Times Educational Supplement 17.3.78.

Oh, look out, William Morris,

We knew you wouldn't die,

But you'd better go and find yourself

A decent alibi.

Our times have re-discovered you,

So they're searching once again,

To blot out that bold vision

And still that fluid pen.

For our policemen do not like you

And are launching an attack,

For you were looking forward

And they are struggling back.

Your ideas are far too modern

And still retain a certain power,

They might worry restless children,

Oh, they shouldn't be allowed.

The ice is breaking up again,

The river is in flood,

New energies assert themselves,

And courage is renewed.

So look out William Morris,

We knew you wouldn't die,

But you'd better go and find yourself

A decent alibi.

Ken Worpole

THE FIRST MILLION POUND POOLS

WINNER

Eddie reached forward and pressed the 'On' button. It took

an age to warm up, that little second-hand, black and white, unlicensed

television set. At last, though, a faint and flickering picture appeared on the

screen.A newsflash- "It has just been announced by the Littlewin Pools Company

that someone in London has become the first million pound pools winner.

Representatives from Littlewin's are now on their way to tell the lucky winner,

believed to be a married man with one child, of his unprecedented win. The

winner is said to live in the East End."

Eddie had a feeling in the pit of his stomach. His legs

felt weak and no fit support for his heavy, suddenly very heavy, body. He knew

it was him.

"It's me, or rather it's us !" he called to Samantha, his

wife and mother of their child, the proof of which was burping under her arm.

"What do you mean ?" she asked.

"That announcement on the telly just now. Didn't you hear ?

It was about a million pound pools win"

"A million pounds ?Did they mention us by name ?"

"No, but I know it's us. You know I never bother to check

the scores properly. I guessed we had something but I just couldn't be bothered

to work it out."

Samantha's face twitched and then grinned spasmodically.

She put the child down and let it scramble round her legs.

"If it's true", she qualified, 'if it's true, we'll be free

from all this at last". She pointed to the room, cushions and wooden table

arranged on bare floorboards.

"We can buy a country mansion", she went on, "and have

lions and tigers in the grounds. We can go on a world cruise. We can be like the

people in the Martini adverts. We'll send baby to Eton. Trade in the bike for a

Rolls. Go on the Russell Harty show maybe. We can, we can do anything we want

to". Her voice trailed off and she held her hand up to her scalp giggling

nervously. Eddie had gone quiet.

"We can buy a race-horse", Samantha shouted suddenly, 'We

can go ski-ing, get an original painting for over the fireplace. We can have a

maid and a servant and a cook".

Eddie wasn't feeling weak or worried anymore. He was

feeling through his pockets, empty save for a bus ticket. He searched them over

and over again. He went to the hall and sorted through his tatty jacket pockets

and then all the pockets of his jackets and coats upstairs hung on a rail behind

a ripped curtain: jackets and coats he hadn't worn in months. He checked through

the bills and summonses behind the broken clock on the mantelpiece and searched

beneath the pile of art and poetry magazines in the corner. He could hear

Samantha downstairs talking to the baby:

"We'll have goats and geese and teddy

bears and go to the Bahamas". Eddie came downstairs, just a little pale-faced.

"You have posted it ?" Samantha asked quietly.

"What ?"

"The pools coupon. It's like some cheap comedy show and you

haven't posted it, have you ?"

"Oh, yes, I posted it all right, but then we don't know

it's us that has won, do we ? Not for sure".

"You were sure a minute ago".

They could hear the car from a long way off, even though it

moved with that soft purr that all Rolls-Royces move with. It slid into view

from around a crumbling graffiti-decorated wall and pulled up beside the house.

The peak-capped chauffeur in the front turned his head, and his nose, upwards

towards the house.

"The landlord doesn't usually come to collect the rent

himself, does he ?" said Eddie.

"That's not the landlord", said Samantha. "Don't you

realise, it's the man from the pools".

Two bowler-hatted gentlemen, complete with rolled umbrellas

and briefcases got out from the back seats. They swung open the gnawed wooden

gate on its one hinge and stood on the doorstep. One pressed the bell, which

didn't ring, and the other lifted the knocker, which came off in his hand.

"I say", called one to Eddie, who was peeking out from the

front room window. "Are you Mr Edward Dorn ?" Eddie jumped away from the cracked

pane and looked, somewhat nervously, at Samantha.

"Well, aren't you going to let them in ?" asked Samantha.

Eddie said nothing but made a dash for the front door,

pulled up the safety catch and bolted it top and bottom.

"Hello, hello, Mr Dorn. I think we have some rather good

news for you."

"What on earth are you doing ?" said Samantha. "Don't you

realise? They've come to tell you about the win, a million pounds, a bloody

million pounds".

"Look, sit down on the stairs Samantha, just a second".

One of the bowler-hatted gentlemen outside began to rap the

glass with his knuckles:

"I say, Mr Dorn, we are from Littlewin Pools and I

think we have some rather good news for you".

"Samantha, as you know, I am at last having a little

success with my poems"

"Your what ?" Samantha half laughed.

"My poems. In the last six months I've had two published in

CRAP, the Counter-culture Revolutionary Arts Press".

"Eddie, dear, excuse me for a minute while I get the

picture. There are two men on our doorstep begging to give us a million pounds,

and you lock them out and start talking to me about your poetry; I mean, what's

the connection ?"

"Samantha, I'm twenty-eight. I have been writing poetry for

fifteen years now, for the last five to the greater glory of socialism. People

tell me how much they enjoy my work. I am respected. For the first time in my

life people are listening to what I have to say. And now look what happens: I

win the bloody pools. Who is going to take my work seriously now ? A millionaire

poet ? I didn't want to get famous this way".

"What, then, dear, are you proposing ?" asked Samantha,

very calmly, very sarcastically.

"I am proposing dear", he replied, "that we refuse the

money". Samantha exploded.

"What ?We live in a crummy house in the

crummiest part of town, we've got a kid we can hardly support, you're on the

dole, and you want to turn down a million pounds for the sake of a few crummy

poems".

"I say, Mr Dorn, can you hear us ?You've won the pools you

know. You've won a million pounds", said one of the gentlemen on the doorstep.

They rapped the door together.

"Crummy poems !" said Eddie. "Crummy poems !" Eddie

thundered up the bare wooden stairs past Samantha and was down again almost

immediately, a wad of scribbled paper in his trembling grasp. "Crummy poems, eh?" He thrust a written-on cigarette

packet before Samantha's astonished gaze. "This one, it's about Chile. I've had people invite me to

read it in pubs".

"Coffee!" exclaimed Samantha. And it was Eddie's turn to

look astonished. "It's one pound fifty a jar now, you know I Do you realise just

how poor we are ?"

"This one here. This poem's about racialism in the

professions".

"Shoes for the child. They're over a fiver, for his little

feet !"

"Royalty. I've written a satirical poem about the Jubilee.

It's called Revolt of the red carpets"

"Rent. We pay seventeen quid a week for this dump, and the

flush in the toilet doesn't even work".

"I'm working on a poem right now on the very subject,

dear," said Eddie.

"You'd be better taking a plumber's course", said Samantha.

"Don't you realise you'll get what you like published now that we are rich and

famous ?"

"Yes, but don't you see, I'll never know if I could have

made it on my own", explained Eddie. "Here, this is my latest ..."

They both turned to look at the front door. Something was

being pushed through the letter-box. It was a cigar, and it was lit.

"You can't tempt me with that !" shouted Eddie at the door.

"Come on you silly bugger, open up!" said one of the

gentlemen, his voice angry now. "This is most embarrassing".

"And if you didn't want the money, why did you fill in the

coupon in the first place ?" said the other.

"In the first place", said Eddie, "You shouldn't be

listening to my private conversations".

"Private ?" echoed the gentleman. "Haven't you looked at

your television lately ?"

"And in the second place",

continued Eddie, "you can get

your bloody cigar out of my letter-box. It's unhealthy and we've no ashtrays".

Samantha got up from the stairs and went in the front room

where the small set was quietly entertaining itself. By the time she had hit the

top of it a few times to try to obtain a watchable picture, Eddie was beside

her.

The scene they saw was of a small broken-down terraced

house. The camera panned in on to the torn curtain around one of the windows and

right into a dingy room. Eddie was speechless. He raised his hand and pointed to

the screen. On the screen a man stood pointing at his television set and on the

screen a man stood

"It's me, or rather it's us", said Eddie. "The cheeky

swine". He ran to the window, and on the screen a man ran to the window.

"They've got a bloody camera out there !" he called to

Samantha. He drew the curtains together harshly; on the screen a man drew the

curtains together harshly. A voice from the television:

"At number fifty-nine they seem to be quite shy. There is

obviously a lot of embracing going on in there between husband and wife. How

joyful Mr Dorn-as he has now been named-must be to be the first million pound

pools winner".

Eddie returned to the front door, the outside of which the

gents were now trying to batter down.

"Oi, you two. Do you know that little box on the coupon

where it says 'No publicity' ?Well I thought I ticked it".

"That may well be, old boy. But you can't expect to keep a

million pound win quiet, can you ?We can't lose all this publicity. Our jobs

rely on this. Come on, let us in".

"I don't want the money, I'm a poet".

"A what ?We heard you were an unemployed miner", said one

of the gentlemen.

"That's it, have a go. It's not my fault if there ain't no

mines in the East End, is it ?" said Eddie snarling. "Take yer money back".

"Take it back? We don't want it. What will the public say if we don't pay our

winners ?'Cheats' they'll call us, 'Cheats'."

"Give it to charity".

"We already give enough to keep our accountants happy".

"Keep it yourself then".

"Us?We're on a salary," said one

of the gentlemen, mystified.

"With a graduated pension, too", added the other.

"It's yours, please take it. You can still write poetry".

"No, I can't. Starving artists produce the best work !" he

bellowed.

The baby was crying now and Samantha was still watching her

own house on the television.

"We'll be able to go to all the jet-set discos", she said.

"The perfect rags to riches story. We'll meet Princess Margaret, maybe even

Roddy".

Eddie started to shove his scraps of poetry under the front

door.

"Read these", he called to the gentlemen. "You'll be able

to tell that I could have made it on my own"

"He's gone barmy", he heard them say.

"We'll have three cars each", said Samantha. "A yacht, an

aeroplane, a castle in Spain". The baby screamed.

An aerial view of the area and the house appeared on the

small screen. The commentator said:

"Newspapermen from all over the world have gathered here

today to congratulate this happy couple on their unique win. The Queen Mother

herself has agreed to present the cheque to them on world-wide live link-up

television next Wednesday".

"We're made !" screamed Samantha, shaking and giggling.

"I'm ruined l" screamed Eddie, shaking her in the hope of

bringing her to her senses and then letting her go when he realised he was

losing his own.

He ran up the stairs, the

banister splintering and

collapsing in his furious grip. At that moment the gentlemen finally burst in

through the front door.

"Just in time as well by the look of it", said one and

picked up the bawling child.

"Quite right", said the other comforting the

near-hysterical Samantha in his arms. She sobbed into his clean, white

shirt-front. "It's all right", he said, "you're rich now"

Way above, Eddie clambered up the dangerous ladder to the

attic and smashed his way through the shoddy repairs the landlord condescended

to do when they had first moved in. He wriggled on up past the chipped slates

and on to the roof.

"Get lost, you lousy bastards!" he shouted to the circling

helicopter and its whirring cameras. He clung precariously on to the fragile

chimney stack and waved a fist to the heavens. "Go away, I don't want your

bloody money I"

Samantha and the gentlemen were watching him on the

ever-fading and buzzing television screen. The commentator was saying:

"And here he is, ladies and gentlemen, Britain's newest

millionaire. He is waving to us now. How happy he must be. He's calling

something to us but of course we can't hear him. From here it looks like he's

saying, 'Thank you!."

Roger Mills

LORD STREET REVISITED

I'm out on the road and short on the coin,

I've got a million friends,

Gonna kick me in the groin,

I feel like an actor,

Looking for some scenes,

Still there's no use in crying over,

Spilt beanz.

The man at the top's,

Gonna call out the cops,

Gonna pull out the stops,

Gonna work until he drops,

Gonna make sure you do,

Exactly what he means,

Still there's no use in crying over,

Spilt beanz.

The man in the middle's,

Got his eye on the door,

Got his nose in the air,

Got his ear on the floor,

Got his morals on the line,

Got his hand in his jeans,

Still there's no use in crying over,

Spilt beanz.

We've got cities full of immigrants,

Dancing in the nude,

Eating our women,

And sleeping with our food,

They talk in funny languages,

I don't know what it means,

Still there's no use in crying over,

Spilt beanz.

Crooked politicians preach in the street,

Put chains on your brains,

And reins on your feet,

Tell you to cool it,

Turn down the heat,

Take all the taste,

From the food that you eat,

Quiz you, whiz you,

Tell you you're beat,

Tie you, buy you,

Wrap you up neat,

They talk in funny languages,

I don't know what it means,

Still there's no use in crying over,

Spilt beanz.

So don't point your finger,

Don't hold a grudge,

Living's your jury,

And death is your judge,

There's nobody a straight man,

Because everybody leans,

Still there's no use in crying over,

Spilt beanz.

Pete Farrow

RICHMAN POORMAN BEGGARMAN

The rich man plans our future,

While poor brothers make the roads,

For them to grind down, with fast motors

Leaving dust and grime and crime behind,

People tell me how come

Poorman work himself dry,

Beggarman ... satisfied?

The Guinea-gogues, fly supersonic planes,

First-class section, on their trains,

Say it time and time over again,

"Segregation is my game",

Won't you tell me why?

Poor folk seem satisfied,

To hang down their heads and cry.

The richest people on this earth,

Are a mean and racist class,

Eating big-broad T-bone steaks, drinking wine,

Poorman, Johnnie-cake and lemonade,

So, open up your eyes,

They're always preaching lies;

Saying "Your riches are in the skies,

And you must be satisfied."

W Lloyd Thomas

A

START IN LIFE

“And this” shouted the foreman into me young man's ear is

the the press shop".

The smell of oil had started at the factory gate, with the

lad wondering if he would be sick or if it would go, and it had gone slowly. But now this noise, this sheer volume of sound that

hammered through his shoes as he stood; this robbed him of his senses, his

thoughts beaten by the rhythms of the nearest press.

"Follow me", shouted the foreman smiling at the boy's face,

"Follow me”

And the boy followed, as close as he could, trying to step

with the foreman's shoes. And as he walked, avoiding the machines, he began to notice

other things, the rolls of shiny steel, the drums of oil, the pellets and

containers and people-a workforce standing, sitting, working very close to the

noise, and little by little by little by little, as his ear grew used to the

noise, the fear died down.

"Don't worry," shouted the foreman, "you'll get ...." and

the sound ate the foreman's voice. The boy nodded, tried to speak but could only

smile, shake his head, and nod again.

"And now" said the personnel manager in the administration

building, far from the rhythms, stretching his arms behind his head, leaning

back on his chair, looking away from the lad, out over the roof tops and away.

"And now-where was I ?"

"Urr, umm" said the lad, feeling he'd failed some test.

"A pencil, a pencil !" said the man and began to rummage in

his desk. Now sitting uncomfortable at another desk in the outer

office and weighing the weight of the man's expensive pen, the lad began to read

the questions again.

At last, carefully, not wishing to leave finger smudges on

the company's 'clean' printed sheet, the lad wrote in his best hand, yes to

every illness then, sometimes no or never, in every other space.

Bob Drysdale

JOBS FOR ALL

"Betty Smith" said the Preacher

"was a great worker,

and an example to us all."

"Much she suffered

and it may be as well

she left us when she did.

For she would have been

sorely grieved at having

to leave the work she loved."

Raising his eyes to the rafters

he added for all to hear

"There's no lack of work up there."

Some of us who had spent

the last year on the dole

could hardly wait to enrol.

Bill Eburn

Copies of FELLOW TRAVELLERS, a booklet of poems

by Bill Eburn, can be obtained from the author at

162 Nether Street, London N.3 for 35p (including P+P).

LINDA WELLER (Manchester) here introduces a letter written

in 1945 by her father PHIL KAISERMAN.

LINDA WELLER WRITES:

The most treasured possession I have is a letter written to

me by my father on the occasion of my birth.

When I was four days old my father received a cable telling

him of my birth, He was stationed in India at the time. For him like many others

the war was a traumatic experience and he obviously felt the need to put down in

writing what he felt at the time and what my birth meant to him.

When I was very young my father was not around very much.

He was usually at union or CP branch meetings, or out selling the Daily Worker,

but in my teenage years for no apparent reason he became less active, which gave

us more time together to talk about life and what was going on around us.

When I eventually joined the CP it was because I had

arrived at a time in my life when my children were growing up and needed me

less, which gave me the time to think and to decide in which way I wanted my

life to go. A few months after joining I came across the letter which had been

put away in a safe place. On reading it I realised that I was taking the same

road as my father, the one he had wanted for me from my birth. I also realised

that what had brought me to that road was not the political problems and

discussions he had faced me with, but by the constant strength of his love

around me and the warmth and friendship he felt and showed to his fellow human

beings.

He always and still does believe that we must be the

masters of our own destiny, but there is one thing over which we have no

control, that is our parentage. Lady luck must have been with me at my

conception to give me him, this man who is not just my father but my Comrade.

LETTER FROM FATHER TO DAUGHTER

|

CERTIFIED A TRUE AND ACCURATE

COPY |

3209SG |

|

|

RAF |

|

|

SEAAF |

|

|

|

|

|

22 April 1945 |

My dear Daughter,

I have just

received a cable telling me that you have just been born. Well this might seem a

little silly writing to a new born babe, who naturally can't read what I've got

to say. Never the less I feel that I should like to put in writing my thoughts

on this occasion.

You have been born at a time when the whole World is

engaged in a conflict to ensure that you and your generation will not have to

undergo the hardship and tribulations that I and thousands of others have had to

go through. Your generation will see a new World, a World in which Man will live

at peace with his neighbour and will go forward to greater and better things

than man had yet known. Your World will be one of Comradeship and communal

effort where each will work for the benefit of the whole community and not for

his own personal gain. I am as sure of this as I am that the forces of progress

will overcome the forces of reaction in the present struggle. The reasons I have

are many, I have listened to many men talking of what they want when this

horrible War is over and by their determination and courage they will achieve

this time what their Fathers lost at the last War. All over the world men are

showing by their actions that they mean to have that Heaven on Earth and the

Homes fit for Heroes to live in.

So, I say that your generation will live on the fruits of

your Fathers endeavours, because I know that all the Parents and Parents to be

who are taking part in this conflict mean to see to it that their Children and

their Children's Children will not have to go through all the horrors of War and

the World will not know again the effects of unemployment and poverty.

Your birth is coincidental with the birth of a New World,

see to it that you take your part in fashioning it and moulding it to our World

of Peace and Plenty.

So, I greet you into this World and hope that you will

carry out your part in the fight for a better World.

(signed) All my

Love, Dear,

from

your Loving Dad

WHY DO I STEAL CARS?

Mom was out at work

and I was on a shirk

and reason was slipping

why I wasn't onto them.

I was out of lighter fuel

I was out of school

and we couldn't pitch a tent

outside the settlement

so what we do

now what we do

we took a motor-car

and rode and rode

into the hills.

The pavements they were high

with the city guys' GXI

and the XL17 they used to carry them.

Now the hub caps they were clean

and the radiators mean

as the b's that had the bread

to purchase them.

The traffic stanchions were down

I say: were down

were down

on my life as a pedestrian.

Everywhere I should plate

there were gans. they were gans

there were gans to put an end

to my life as a pedestrian

so what we do

now what we do

we stole a motor-car

and rode into the silver hills

of Sodomen.

Now the tenements were high

Yes they were high

as they were long

as they were broad

to conquer them.

I threw a desk, I say a desk,

at the teacher teaching us

about Bethlehem

so what we do

what would you do

what can you do

we stole a motor-car

and rode into the hills

the purple hills

to find this Bethlehem.

So we rode and yes we rode

cross 4 bridges and suspension

turnpike flyovers

and rode in search of Bethlehem

All aside us sand hills moving

and river valleys grooving

Until we found what Toxteth

library promised us.

We found an old vineyard

where the winters set in hard

and we smoked and smoked and smoked

colour supplements

we made a fire of stone

from the vines that'd overgrown

and the water from the stream

was to nourish us.

Yes the tenements they were high

were long as they were broad

to conquer them

and the squad cars and traffic stanchions

and the city welfare mansions

had put an end to my life

as a pedestrian.

So what could you do

what would you do

I'm asking you.

You'd steal a motor-car.

John Gowling

BLUBBER

November. In a city street

I passed someone I thought I recognised:

"Blubber !" I blurted out.

Blubber. It was the name we gave at school

to a queer shambling nervous pale-faced lad.

No-one remembered why, yet somehow it suited him.

But when we jeeringly called it after him

he always hesitated for a bit

then smiled good-naturedly.

He takes it in good part, we said,

and so we justified our plaguing him.

Yet I sometimes thought he swallowed our insults

because he preferred to have some friends like us

to never having any friends at all.

Yes it was he-I was right to call out Blubber in that city street.

Mutual recognition after fifteen years.

He hesitated for a moment, as of old,

then snarled and cursed me and went upon his way.

I stood there shocked, but yet perversely glad

to see that Blubber had become a man.

Donald Whitmore

THE CONCRETE GROUND

The concrete ground gleams,

A mixture of rain and sun,

Five boys head and kick

A ball that springs with jitters.

It's teased and bounced

Over crossbars and roads.

The latter suffers traffic,

Wild, excited, nervous and fast.

Meanwhile, the boys are picking roles,

Famous names are tossed and scattered.

This concrete ground,

That grazes knees and tortures feet,

Is not Old Trafford or Anfield

But it suffices.

The roaring cars, like the Kop

For eleven clad in red,

Is support for the five

In fashionable rags.

Their green turf is grey,

Their netted goal-posts

Are bent metal engraved with

"Ezer's and Steve's",

Their commentators

Are breathless scorers of imaginary goals,

Their Wembley is this concrete ground,

Provided by penny-pinching planners

In an effort to make the kids happy.

The kids are lucky to have their dreams.

C Mooney

THE MAN ON THE HOSS AT DURHAM

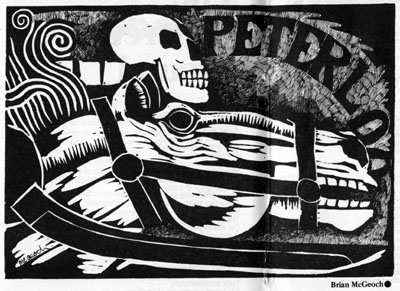

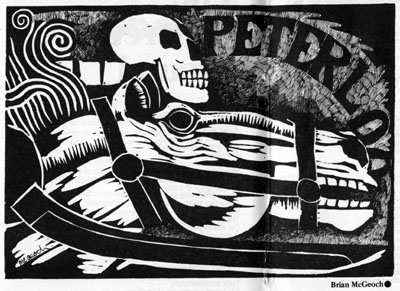

To me the monument in Durham Square is one of hate

and oppression. Lord Londonderry or Castlereagh.

Castlereagh, the Home Secretary, shot them down at Peterloo;

his son or brother, the one on the horse without a tongue,

trod them down. Shelley explains it very well.

I met murder on the way

He had a mask like Castlereagh

His face was firm, but he looked grim

Seven bloodhounds followed him

They were fat and well they might

Be in most admirable plight

For one by one and two by two

He tossed them human hearts to chew

and this is what I came up with myself:

As I was out one summer day

I met my Lord of Castlereagh

Upon a horse in Durham Square

There's something wrong I do declare

A stallion carved, well-shod, well-hung,

It's standing there without a tongue

If words could speak what would it say?

Get off my back, you Castlereagh

Dickie Beavis

You gave space in your last issue of VOICES to a working-class army

officer with his poem on Northern Ireland (not Ulster) and those who

will die there.

May a working-class railway guard be given the same space to reassure

the working-class officer, his fears are not groundless. He will not be remembered.

I have read about half of your issues and I hope this is the last time I have

to reply to such a poem.

I don't believe in letting the enemy have a word in edgeways. If that working-class

Major isn't the enemy I'll eat my guards red flag.

I WILL NOT REMEMBER YOU WHEN YOU’RE DEAD

I Will Not Remember You

When You're Dead

(Not a dedication, not an oration)

I will not remember you when you're dead

you're not that complex.

Your actions basic bullet is a fraud

like the romantic lily,

like the environmental wrench your words

are not that complex.

I will not remember you

remembering who to blame for what you are

I will not remember your naming game,

your port-arm words today.

My celebrations will have nothing to do with killings

on streets you may have helped to die.

Your numbers up and you know it

or maybe you don't,

either way, you're right,

I'll not remember you when you're dead.

Joe Smythe

About two years ago the British Authorities decided that as part of their campaign

against those fighting them in Northern Ireland, that they would replace detention

without trial by the special no-jury courts, and that political status-the wearing of

civilian clothes etc in prisons-would be abolished. Kieran Nugent was the first of hundred

to refuse to co-operate with these attempts to criminalise political activities.

For two years now he has refused prison uniform, resisted prison discipline.

There are now over 400 men 'on the blanket' in the prisons of Northern Ireland.

POEM TO KIERAN NUGENT

Naked

as the day you were born

but without that innocence,

stripped

of everything

but pride and honesty,

how dare they,

who clothe

five hundred years

of oppression

and deceit

in words of moderation,

presume to judge you ?

and how dare I

who has no more than mouthed

my disapproval

presume to call you

comrade?

Phil Boyd

ME MEDALS

"You're a bit

of a flamboyant bastard aren't you !" Sol burst out. After a couple of jars of

draught Guinness that hurt a bit. We'd just come out of the "Ducie" after having

a particularly enjoyable evening, everybody participating in Irish fiddler music

making, some tapping the table with coins, others playing with spoons or 'rickers'

as some call them, the rest making noises of their own choice, but everybody

participating and enjoying the bearded Irishman's melodiousness.

"What makes

you say that, you schnook faced git" expostulated Stan.

These two

were always extremely correct and complimentary in each other's company. They

would sometimes boast who cooked the best meal whenever they were in each

other's homes. Like 'cowshit', 'drecht' or 'prison poison' just to show how they

enjoyed the culinary expertise of the other.

Sol gave Stan

one of those wild hairy faced looks that he was expert at, and said

"Fancy

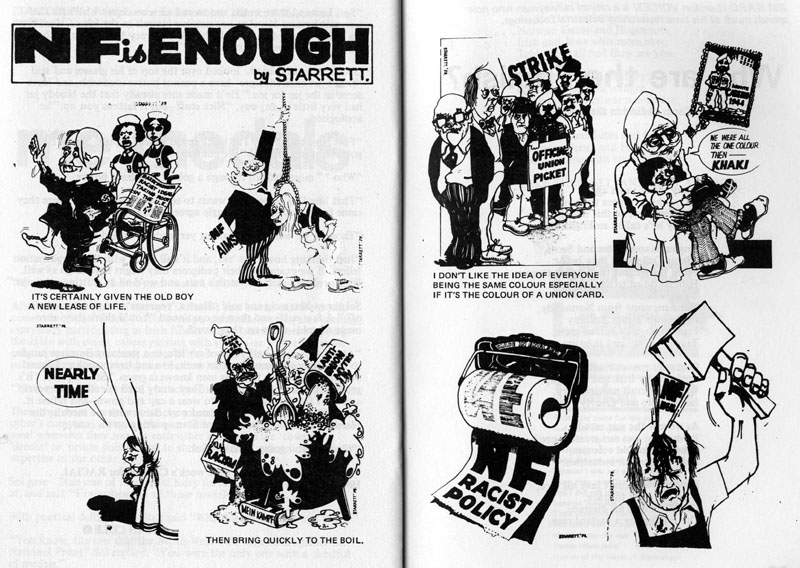

wearing all those medals on a demo." With poetical

deliberation Stan said

"What bleeding demo was that ?"

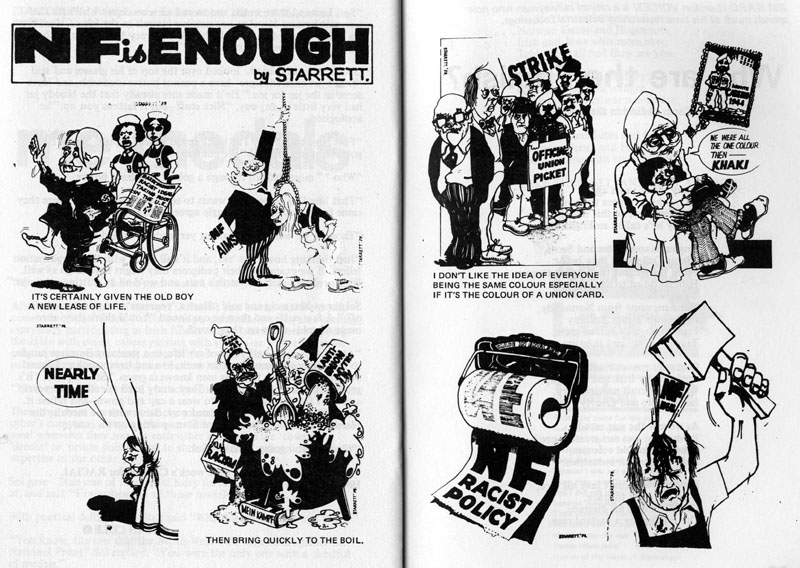

"You know,

the one that the North-West TUG organised against the National Front" Sol

replied.

"You were the only one with a chestful of medals."

"So! I

earned them in the war to end all wars didn't I! Whilst that arrogant bastard

Moseley was sunning himself in the Isle-of-Man. Now his followers want to defend

White Democracy by sending all the blacks back where they came from." Sol scratched

his head, looked over the top of his glasses and said

"Don't get excited.

Here-have a peanut butter sandwich, and leave some in the jar for me." He'd made

sure already that the bloody jar had very little in anyway. "Nice stuff-but it

fattens you up," he apologised.

"Fine time to

tell me. The black bread's nice" replied Stan. "He's got a right bleeding job",

he continued.

"Who ?"

mumbled Sol through a gobful of peanut butter.

"That

bleeding geezer who wants to send everybody back where they came from-and I

notice Maggie agrees with him."

"Thought we

were talking about yer medals" mused Sol.

"Just

thinking how I got 'em, and it's all to do with these repatriation fellers. If

we examined their pedigrees they might have to go as well. We'd probably shift

the earth's axis, and we'd all be shitting sideways."

Sol threw him

a cig and said

"Have a 'yennims' and cough yer balls off." A few puffs and then

he continued "You'd think they were made of gold-what are they worth."

"About

five-and-a-half years of my life, in a steaming Burmese jungle, so that we could

come back to work, live and love together. I found out the only colour the boss

man knows is green." Stan replied. "It's getting the same with our kids. They

study hard at college for years, and fight for the entitlement to wear a cap and

gown-and refuse it. Why ! They've earned it-the hard way. Same with me medals,

the bleeding hard way !" continued Stan-putting on his coat.

"Where're you

going ?" asked Sol.

"To polish me

medals for next week's Carnival for RACIAL HARMONY."

Stan Cole

WHO ARE THE ENGLISH?

(Tune: "Island in the Sun")

Many many years ago,

As our history goes to show,

Invaders came to this island,

Today he's called an Englishman.

Angles Saxons Jutes and Scots,

Viking Danes and they begot,

From them came the English tongue,

Handed down to daughter son.

Normans came from Normandy,

Huguenots from Brittany

From them all a nation grew,

Take them all, and they are you.

Centuries pass our nation grew,

Enriched by Irish and the Jew,

With their craft and industry,

Love of life and Liberty.

As we saw the war recede,

Production was our greatest need,

Labour from old colonies,

Help to man our industries.

Enoch Powell can't save his face,

If he ever tries to trace,

He will find to his disgrace,

The English are a bastard race.

Angles Saxons Jutes and Scots,

Norman Danes and Huguenots,

Irish and Jews with races new,

Take them all and they are you.

The lessons of our history,

Of immigrant and refugee,

Took them all in warm embrace,

Absorbed them in our island race.

Angles Saxons Jutes and Scots,

Normans Danes and Hugenots,

Irish and Jew with races new

TAKE THEM ALL, AND THEY ARE YOU.

JIM WARD

JERSEY HOLIDAY

Jersey (bays and steep-banked lanes,

paddocks where creamy cattle graze,

small vineyards, solid pink stone farms,

old churches, lazy long-stretched strand)

You are no holiday resort-it pours.

We drive through endless maze of streams,

on silver mirrors of the sky

along the cliff's brink, blurred by rain.

You should be sun soaked; so should we,

sprawled warm and naked on the shore-

not drenched, chilled, hunched into ourselves,

sheltering separately in our clothes.

And we rain too: showers, cascades;

puddles reflect our shuddering forms.

Rain drops studded on the leaves-

tears fallen from our weeping eyes.

For we are not as we had supposed

linked together, minds entwined.

Water trickles down the rocks;

rain drops spray off into space.

Nor is this island what it seems.

Beneath the pretty pastures-caves.

Bygone barbarism lurks

in deep-ground tunnels, caverns hewn

by broken bloody hands of slaves

labouring under brutal guards

burrowing bunkers in the depths

of Jersey, underneath the grass.

Then, it was secret chambers carved

by "untermenschen", Poles and Jews;

but now across the narrow sea

deadlier contraptions lie in wait,

all set to exhale nuclear gas,

poison the people, wither fields,

blacken hedgerows, kill the cows-

we realise it is time to leave.

Suddenly the deluge stops.

(Bunker slaves went long ago)

People rise to quell the fumes.

We are together. Free. We stay.

PAT ARROWSMITH

THE RISE AND FALL OF THE ENGLISH PUB

They hung a star above the door

They promised warmth and cheer

A game of darts, a cosy fire

And a glass of honest beer.

And that was how the English pub

Became a 'Way of Life'

Where tales were spun, and jokes were swapped

And a man could take his wife.

And many merry nights were had

For that's what pubs were for

And everyone paid homage to

The Star above the door.

But nothing ever stays the same

At least that's how it seems

Perfection is the kind of stuff

That only lasts in dreams.

The Breweries that owned the pubs

(There's none knows how or when)

Were taken over by a group

Of grasping, greedy men.

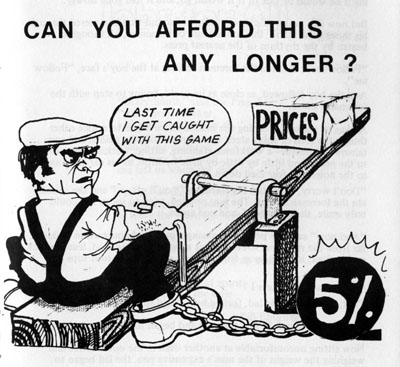

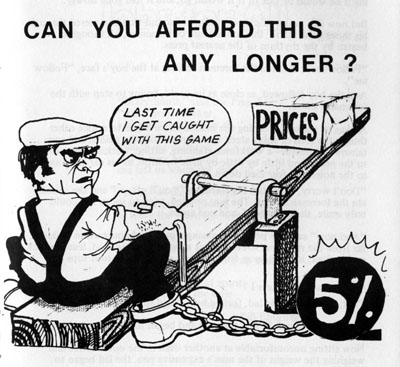

Throughout the nineteen seventies

Like vultures at a kill

They exploited every avenue

And the public paid the bill.

With every chance, in dribs and drabs

Their prices rose a penny

Their beer became a luxury

And out of reach of many.

Their profits broke all records

As they watched their prices soar

But the public turned in anger

From the star above the door.

Now they're poorer but they're wiser

As they leave their once-loved pub

And they re-direct their footsteps

To their local Social Club.

And each one will be accepted

As a member and a friend

And once more they'll get true value

For each penny that they spend.

May this story be repeated

In each corner of the nation

Down with those greedy breweries

LONG LIVE THE FEDERATION

Ripyard Cuddling

A DAY IN

THE PARK

Old Tommy

came up out of the tunnelled estate and wavered at the crossing, cursing at

himself against the torrent of traffic slithering past like a long silvery snake

of a train. A snake with neither head nor tail, its body huffing and puffing and

snorting along, until severed by the bright red eye of the iron policeman. But

even then it was not safe. Many is the time that Tommy had hardly completed the

dash for the opposite side, when the eye had flickered to amber and sent the

straining serpent galloping off in hot pursuit of its severed front.

Having

eventually got himself safely across the road, Tommy set himself a roundabout

back street course to the park, in order to evade being waylaid by gangs of

neighbours, who, since his recent fall, seemed to be lurking about all over the

place and falling over themselves to help him with this, and wash or press that.

Or even worse; on a Wednesday, commandeer and cook him the piece of meat he was

saving for Friday. He had tried for weeks to convince them that it was the drink

rather than the senility they suspected, that had sent him on a helter-skelter

tumble down the concrete steps, but it was all in vain. Still the meddlers

meddled, and his only relief from their meddling was his daily walks across the

small stump of grass at the park which had become his sanctuary.

He stopped

awhile at the south gate, to give himself a bit of a rest, before he took his

old stick tap, tap, tapping, away off to the keeper's hut and his regular mug of

afternoon tea. He gazed around for a time, reflecting on the years before his

retirement, when he had worked in this same shabby little park. Wasted years,

spent standing sentry to the pampered rows of plants and flowers, and sparse

patches of polished grass, all long gone now. Now as winter approached all that

remained for a weak city sun to peek at as it sunk behind the fringes of

withering trees, was a lunar landscape of burning mounds of rotted leaves. Tommy

shook his head sadly. The place was becoming as bleak and desolate as the wastes

that drew themselves about its edge.

Tommy pushed

in through the door of the hut, straight into the middle of a row. Lenny and

Charley were locked hammer and tongs across the table. Behind them, doing his

utmost to ignore the bickering, sat Ambrose pulled up to the oil stove in the

far corner. Pointing to the teapot he passed up a mug to Tommy.

"Go on it's

just brewed." Tommy poured himself a good measure and took up a seat with his

back to the window, and asked:

"What's all

the row about then Lenny ?" Ambrose answered him:

"Damned

politics again. What else ?" Lenny broke off the bickering and turned to Tommy:

"What else

indeed, eh Tom. Politics the struggle of life." Tommy laughed.

"Don't

involve me son, thankfully I'm past all that."

"Nonsense

Tom, nobody's ever past politics. It's there strapped to our backs like our

class, from our first cry to our last sigh." Charley, who had obviously been

getting the worse of the argument before Tommy's arrival, and who had been glad

of the short diversion, shaped up and moved back into the fight.

"Class,

class, what bloody class ?" He took a sudden gulp of half cold tea and

spluttered: "That's the

trouble with this bloody country, class; you're all bloody well obsessed with

it. You've got a class for everything and everybody, with each level fighting

and clawing to keep their own perks and privileges safe from the other." He

swung around to face Tommy, lowering his voice as he spoke. "What we need

now Tom, is a new movement all together. One that will unify all of us, the

whole nation, towards a single goal." Ambrose sighed. He had a shrewd idea at

which direction the argument was about to turn, and no doubt the moral level of

debate was about to take a sharp dive. Lenny on the other hand, was absolutely

delighted. He lunged for his newspaper, giving off a bark like a wounded whale:

He shoved the paper under Charley's nose.

"This

miserable little bunch of swaggering fascists wouldn't be your idea of a

unifying movement by any chance, would they? They're the biggest threat yet to

the unity of the British working-class."

Charley was

taken back by Lenny's sudden show of temper and turned to Tommy for support.

"See what I

mean Tom, with this bloke all roads lead back to bloody class."

"Well, isn't

that what it's all about man." Lenny came back at him. "The class war-us the

working-class doing all the producing, and every other class upwards sucking off

the fruits of our labour." Charley took a suck of tea and had another go at old

Tom.

"Go on Tom,

you ask him." Tommy who had only been half listening looked puzzled.

"Go on tell

him what it was that you ever produced apart from piles of rotted leaves, in all

your time in this ratty little park." He paused for a second. "And if the

so-called upper classes want to rob us of that, then for my part they're bloody

welcome to it." Tommy became embarrassed and uneasy at Charley's attempts to

drag him in as an ally. Without answering he raised himself from his chair, and

pushing back the sacking at the window gazed out at the gathering dusk rolling

across the park. 'The conversation behind him receded to a respectable distance

as he watched the spiky skyline set itself up into a sharp silhouette, ready to

scratch at the underbelly of the coming night. Suddenly he was wrenched back to

the foggy reality of the hut. This time it was Lenny.

"Did you hear

that Tom ? Now he says there's no unemployment south of Barnet." Now on this

subject Tommy did know a thing or two; his brother's three sons had each been

apprenticed into different sections of the building trade, and he knew from them

how work came and went with the seasons, and how, on a bad winter half the

industry could be thrown out of work. However, before he could work his thoughts

into words, Charley had leapt to his own defence.

"I didn't say

nothing of the sort," he roared. "All I said

was that we couldn't get people to work here in the park for love nor money'

"Perhaps not

everyone wants to work in the park." Tommy offered. Charley rolled his eyes in

despair.

"I didn't say

they did, did I ? I was just ...." Lenny butted in:

"We know what

you were just doing man: giving out the same sort of trash as that mob you

support. I suppose their answer to unemployment is to recruit a bloody great

army of park keepers, and if we build a big enough park with a big enough

keeper's hut, we can solve the housing problem at the same time !" Tommy

chuckled. But Ambrose, who had been ignoring the row, buried in his paper, left

it down. He sensed that Charley was within a fish's spit of tearing Lenny apart.

Lenny, realising the danger drew in his horns. Not taking any chances, Ambrose,

who was the senior man anyway, got in between them.

"Come on

that's enough. Every time you pair start bickering about politics it ends up in

a fight." Charley pushed himself back in his chair, still hot with the effort of

keeping his temper.

"You tell him

Ambrose ! Whatever I say, he has a go at me and takes the mick." Ambrose patted

air.

"All right,

all right, just calm down for a second. Lenny, you boil up another pot of tea.

Tom will have one before he leaves."

By now the

bad mood of the hut was positively crawling about the place, and though he was

reluctant to linger in such an atmosphere, Tommy agreed to one for the road.

Lenny allowed the temper of the hut to cool before breaking the forced silence.

Pushing away his mug and addressing himself to the company in general, he asked:

"Well, short

of deporting half the population of London, what is the quick and easy remedy of

unemployment." The trap was laid, and Charley, true to form, surfaced, snapping

and thrashing at the bait.

"Look, just

because I bloody well vo ...." He stopped himself and shot a look of

embarrassment and despair across to Ambrose. The embarrassment was mutual.

Charley lowered his voice feeling suddenly treacherous as he spoke:

"Okay. So I

voted for them. So what ?" Lenny gave a satisfied grin.

"Well at

least we all know where we stand now don't we." As he spoke he glanced behind

him to Ambrose.

"But it

doesn't answer the question does it." Charley leaped to his feet crashing his

mug back on the table.

"Sod you and

your bloody clever questions," he roared. The significant glances the others

were firing among themselves put Charley on the defensive. His voice became

tinged with panic.

"Look I'm not

a member am I ?I only voted for them." He flattened his hands in a gesture of

defeat.

"Well what

else can you do? Come on, never mind the dirty looks, how else do you give the

establishment a kick in the pants." An embarrassed silence cloaked the hut.

Tommy turned to gaze out of the window, and watched as a gang of young cyclists

honed in and swooped on the last remaining patch of hemmed in grass. The

formation regrouped and fled, decapitating a solitary line of flowers as they

went. Tommy shook his head sadly. The steam from his mug had misted the glass.

He turned back to Charley, asking:

"Tell me,

son, who exactly do you consider to be the establishment ?" He paused allowing

the question to rest, and glanced back to where rivulets of condensation made

bars at the window. The last of the cyclists had been swallowed and lost in the

gathering darkness. "I mean to

those kids out there all of us here in this hut are the establishment." Charley was

up on his feet with a roar:

"Us, us. How

can a bunch of no nothing no-bodies like us be the establishment." Tommy was

petrified. Charley towered above him, purple in the face and grunting with the

effort of controlling his rage. Tommy struggled to find a way of pacifying the

other, without antagonising and setting him off again. Ambrose dashed between

them and Lenny unobtrusively slid into the vacated corner chair. Charley stormed

away to the door roaring over his shoulder at Ambrose, that if they were all

going to be against him and always take Lenny's side because he impressed them

all with his clever book talk, then they could stick his bloody job and be done

with it.

For a good

while after Charley had left, the tension in the hut was as taut as a fiddler's

bow string. Eventually Lenny announced:

"Well at

least we can agree on one thing, not only is the man an idiot; but a sodding

dangerous idiot at that." Ambrose turned on him annoyed:

"Why an idiot

Lenny ? What is it that makes you his better ?" Lenny was bewildered. Although

Ambrose generally remained non-committal during their debates, Lenny had always

presumed him to be in sympathy with himself and his own politics.

"I don't

consider myself to be superior to anybody", he answered defensively. "Quite the

opposite in fact."

"I agree that

is what you would have us believe. In fact. . . suspect that you believe it

yourself !" said Ambrose.

"Yet look how

quick you are to condemn Charley and his like." Now Lenny was getting mad.

"Well how

else do you treat his sort ? Somebody's got to show them a few home truths."

Ambrose smiled:

"Truth yes,

but it's more than that, isn't it ? You know I think it is because he is a bit

slow, that you actually despise Charley." Lenny was beginning to feel

uncomfortable. He turned to Tommy.

"That is

nonsense Tom: I had no formal education to speak of myself; everything I have

learned I have taught myself."

"Exactly,"

said Ambrose.

"And because

of this you despise all those who are ill-equipped to do the same. All this

nonsense of trying to enlighten Charley is just an excuse to get at him."

"And how do

you come by that conclusion ?" Lenny answered. Ambrose grew serious.

"I just can't

believe that you're seriously attempting to endear Charley to your arguments by

continually lecturing him on the heavy end of Mr Marx." Tommy returned to the

argument:

"He is right

there Lenny, to the average working man all this stuff about international

Marxism and capitalism is just so much intellectual clap-trap, and you can't

blame people for taking more interest in football than politics." Ambrose

slapped his hand on the table.

"Exactly," he

said, returning to Lenny.

"If you want

us to take this socialism idea seriously, then you must bring it down from some

highbrow discussion to a level where it will actively involve and encourage

people like us."

By now a

thick black velvet had blanketed the park and Tommy had to rely on Ambrose to

guide and steady him across the rutted ground. In the distance a solid stream of

headlights washed along the main road. Suddenly Tommy became keenly aware of the

eeriness of motion without sound. He glanced back toward the hut, where Lenny

sulked under the last glimmer of light, and thought on what a desperate place

the park had become. Suddenly he realised that Ambrose had been speaking.

"I'm sorry,

what did you say ?"

"I was just

asking what you made of all this sudden patriotism ?" Tommy thought for a while

before replying.

"I would have

thought that as far as the wilder elements go, they have probably reached their

peak." Ambrose probed a little deeper.

"I noticed back at the hut that your

sympathy seemed to lie with Lenny." Tommy brightened:

"To a point,

yes. Remember, I was one of those who marched against the bosses back in the

thirties and forties, along with thousands of others." He sighed,

tasting the fondness of distant memories. "But then it

was so much different, it was simply us and them. Nowadays, politics have become

a complex game, that I'm no longer sure I can altogether follow." He looked

sideways at Ambrose.

"But what of

your politics ? It is you and your people that should feel threatened by the

likes of Charley." Ambrose laughed.

"It isn't

Charley that worries me, but the apathy of the politicians to the problems of

areas such as this." By this time they had reached the main gate and they stood

awhile staring out through the bars at the squabbling traffic. Tommy broke the

silence:

"So

politically which way would you go?" Ambrose shrugged.

"As it stands at the

moment I'm not at all sure."

"Fair

enough", Tommy replied.

"But you must

have some sort of leaning; I mean I know it's silly, but just for an example,

suppose the whole political debate between left and right was condensed down to

the argument in the hut this afternoon, who would you choose between Lenny and

Charley ?"

"You think I

would choose the same man as you, don't you ?" Ambrose answered.

"I'd be

surprised and curious if you didn't."

"Why

surprised ?" Ambrose asked.

"Oh come on,

I know Lenny can be a little patronising at times. But at least his politics

make some sort of sense. The other fellow has no politics save one."

"Ah, but

these people exploit that policy to a great effect, do they not ?"

"And you

think that commendable ?" Tommy replied somewhat shocked.

"Of course

not, but until socialism is brought down from its pedestal, and put in its

proper place as the everyday common-sense of the working-class, rather than the

debating matter of the intellectual few, then you will have nothing to fight

them with."

"So you think

socialism should change ?" Tommy asked.

"No not at

all, but the way it is presented to people should. Give people something they

can readily identify with for a start. I mean take Lenny and his friends; while

they are busily huffing and puffing quoting Marx at each other at meetings which

only themselves attend, small organised bands of fascists are beavering away

spreading the word in pubs, clubs and factories all over the place." Ambrose

paused, then swept his arm in a wide arc.

For a while,

after leaving the park, Tommy wandered aimlessly about the place, thinking back

on the events of the day, then for a while, he plunged his memory back even

further. A sudden smell of burning timber, somewhere a shop was burning crashing

glass, the mounted police charge, and broken bodies. A counter-attack, the

breaking of enemy lines, the cheers of victory. Tommy stopped and sniffed the

air. Was it all a dream? Fragments of memory retrieved from the past like the

soldiers shrapnel, to delight the children ? Or is it real dream for the future?

Dave Barnes

Hackney Writers Workshop

SLEEPING DOGS

(For Liddle Towers)

Referring to the dead man, Towers,

As a sleeping dog, the Police Federation

Expressed a wish that he be allowed

To lie. But wasn't it for lying

That the man was beaten to death?

After asking him repeatedly if

He was a trouble-maker, and receiving

Always the wrong answer, they had no alternative

But to beat him. And in any case

He didn't die straight away.

The dead man's sister and brother-in-law,

Two electricians from work and the lads from the club,

And Mrs. Parker from number .7,

All agitators if ever I saw 'em,

Went down to the Police station to protest

About the police.

Sergeant Bull, sergeant-major ex-army, told

Mr. Kay, number 12, sergeant-major ex-army, that

SOME PEOPLE were taking it on themselves to

LOOK FOR TROUBLE and DECENT FOLK ought to

HAVE NOWT' TO DO WITH 'EM. A fair point this-

With the public looking for trouble, Sergeant Bull

Could be out of a job.

The inquest jury, all adults with

A lifetimes experience of recognising

Sleeping dogs which are not to be

Disturbed, saw that this was obviously

A sleeping dog and returned their verdict

Accordingly.

The dead man's mother and next door neighbour,

The lads from the 'Crown' and the union branch,

And Mrs Jones form number 9,

All desperadoes if ever I saw 'em,

Wrote to the Home Secretary to protest

About the verdict.

Sergeant Bull, upholder of moral standards, told

Mr. Kay, upholder of moral standards, that

SOME PEOPLE seemed to HAVE IT IN FOR

The police and DECENT FOLK ought to

PUT A STOP TO IT. A fair point this,

Only some people thought that

Sergeant Bull usually seemed to

Have it in for the public

The Home Secretary, after serious consideration,

Not wanting to rock the boat, but recognising

The importance of sleeping dogs, and that justice

Must not be seen not to be done, decided

Accordingly.

The dead man's girlfriend and her brother

The lads from the 'Fox' and the shop stewards'

committee,

And Mrs. Brown from number 5,

All hardened revolutionaries if I ever saw 'em,

Told the press what they really wanted

Was a public inquiry.

Sergeant Bull, in favour of hanging child molesters, told

Mr. Kay, also in favour of hanging child molesters, that

SOME PEOPLE were NEVER SATISFIED and were

OLD ENOUGH TO KNOW BETTER and DECENT

FOLK ought to

KICK THEIR ARSES FOR THEM. A fair point this-

If people need molesting, we should at least wait

Till they're grown up.

Referring to the dead man, Towers,

As a sleeping dog, the Police Federation

Raised the interesting question: What is

A sleeping dog? Is it something we don't need

To know? Or something they need

Us not to know?

See for yourselves. They have started

Writing it in the back streets,

An item for the agenda of a meeting

Not yet convened , chalked up

On the walls and pavements, it reads:

ONE VOICE MANY VOICES

I am a woman, fighting against the traditions of my people,

I am a woman, I am not fighting against my culture

but against the oppression we face, against the

old-fashioned traditions which will not fade.

I have been brought up in a Western country

I have gone to school along with the other girls

I've watched them dress up in their modern clothes and their make-up,

I've heard them speak of their boy friends and their hopes for the future.

What do I look to, what is my aim in life?

Is it to marry an unknown man and bring forth male lives?

I am a woman, like many other women in my race

I live in a society where men are very dominant

Where their births are a time of rejoicing,

What did I bring but sorrow, loss and pain?

But I'm a woman, an Asian woman and I am proud of it,

But I want to live my life fully, work, and marry whom I please

I do not wish to marry a man my parents pay to take me.

But I am not rebelling against my culture

and so my difficulty is no longer oppression

because the only alternative to oppression is Westernisation

and it is not what I seek,

All I seek is a peace and joy which marriage to some

unknown man does not bring.

So I'm a voice speaking and wishing to be heard

Speaking not just for myself but for many other women

So it is no longer just I, but we, and it's we who are fighting.

VAL McKENZIE

ONE VOICE MANY VOICES

I am a woman, fighting against the traditions of my people,

I am a woman, I am not fighting against my culture

but against the oppression we face, against the

old-fashioned traditions which will not fade.

I have been brought up in a Western country

I have gone to school along with the other girls

I've watched them dress up in their modern clothes and their make-up,

I've heard them speak of their boy friends and their hopes for the future.

What do I look to, what is my aim in life?

Is it to marry an unknown man and bring forth male lives?

I am a woman, like many other women in my race

I live in a society where men are very dominant

Where their births are a time of rejoicing,

What did I bring but sorrow, loss and pain?

But I'm a woman, an Asian woman and I am proud of it,

But I want to live my life fully, work, and marry whom I please

I do not wish to marry a man my parents pay to take me.

But I am not rebelling against my culture

and so my difficulty is no longer oppression

because the only alternative to oppression is Westernisation

and it is not what I seek,

All I seek is a peace and joy which marriage to some

unknown man does not bring.

So I'm a voice speaking and wishing to be heard

Speaking not just for myself but for many other women

So it is no longer just I, but we, and it's we who are fighting.

VAL McKENZIE

POINT OF VIEW

All the

morning she had been telling me about the house they were going to buy. £40,000

in cash. She watched my face each time she told me. But I cannot take in this

amount of money. So I say I have to leave early on Thursday, ten minutes early,

to visit the hospital. I've never had time off from work, never. I am always

there, come rain, come shine. And she says, you must cut the time from your

wages. You must cut ten minutes from £2.15. I don't understand. One minute she

was talking about spending £40,000 and in the next moment she is asking me to

deduct ten minutes from £2.15. The contrast is so ridiculous, that I burst out

laughing, and she backs away from me, for she cannot see the joke.

Joy Matthews

POVERTY SKILLS

I cut my man's pyjamas down

(too patched to take another one)

to make pyjamas for his son.

Bits of old dresses sewed in line

I order in a patched design

for poverty, not filling time.

I quilt old blanket ends together

to comfort kids in bitter weather,

not rich enough to buy another.

As my mother taught I go

up and down each market row

choosing cheapest to make do.

Hours and hours of precious time

put to manage and contrive

to keep us warm and fed and live.

Clever hands and able brain