|

ISSUE 15

cover size 210 x 148 mm (A5) x 2

Editorial Rick Gwilt

Letter Ted Morrison

Scotland Road Writers Group

Whatever Happened to the Good Samaritan? Jimmy McGovern

The Top Shelf Chris Darwin

I Fought Norman Snow Ed Barrett

Poet... Failed Norman Clinton

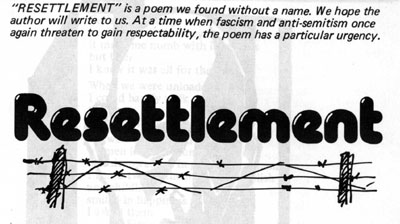

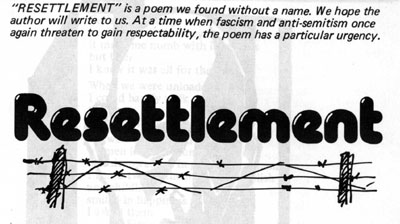

Resettlement Anonymous

Quneitra Giorgio Taverniti

Pie in the Sky Bill Eburn

Two Minutes Derek Lee

Jubilee Mike Rowe

Rent Strike John Koziol

On the Knocker Ken Clay

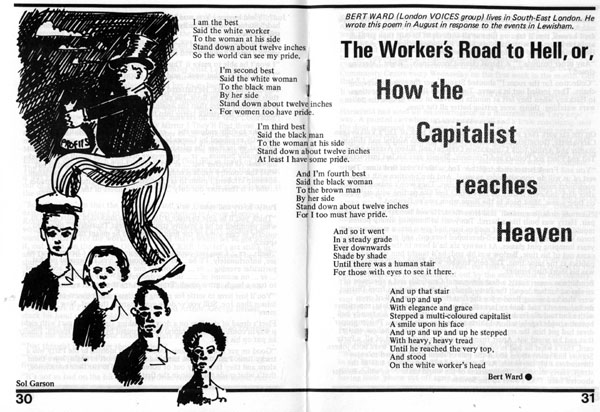

The Workers Road to Hell.... Bert Ward

A Womans Work Jean Sutton

Trico Tom Durkin

Where do you go to my Doris? Les Barker

The Nons Bert Smith

Geordies Alan Brown

Dixie Dean - Footballer to the Queen Keith Armstrong

Canadian Working.Class Poetry Brian Davis

The Last Word Bill Eburn

EDITORIAL

For starters,

I would like to wish Ben Ainley (falsely rumoured to be my grandad) a speedy

recovery from illness, and hope that by the time he reads this he is busy

writing the editorial for VOICES 16. In order to provoke him, I am going to

stick my neck out and say that I consider this edition to be the most definitive

for a long time. Whether it is the right definition of working-class writing, I

am waiting to hear from our readers, but at any rate it is an attempt to answer

that old thorny question:

"What is

working-class writing ?" Is the answer here a step forwards or backwards? Does

this seem a better or a worse balance? The material for this VOICES has probably

been discussed among a record number of people, mainly in London and Manchester,

but the final selection must be blamed on me.

One useful

task that VOICES can certainly help with is discovering a positive British

working-class cultural identity, which is neither obscured by the mass media's

"cult of the common man", nor based on being not-foreign or not-black or

not-female. Many of our contributions already reflect this preoccupation, but we

would welcome more contributions from women and black workers.

We appeal to

all artists and photographers in the labour movement: it is up to you to give

VOICES an Arts section that can stand independently and not simply illustrate

stories and poems. Anything that will photograph clearly in black-and-white-send

it to Sol Garson.

VOICES

returns to its old serial numbering and retains the page with the aims of Unity

of Arts, because it is proud of both its age and its origins. But it is not

afraid to change, especially if it is not living up to the target it has set

itself-to be a publication of the labour movement for the labour movement.

Finally-anyone who sends a s.a.e. I will guarantee to reply to. It would help if

contributors included with their work a short autobiography and indicated

whether they wanted a critical response to their work. We will do our best to

see that such criticism is based on the widest discussion we can manage.

Rick Gwilt-September

1977

LETTER FROM TED MORRISON...

There is a

need to discuss long-term policy of Voices, and has been for quite some time.

But is there need to relate this to the aims of 'Unity of. Arts' ? This

ambitious, if worthy project has been virtually defunct for some years and its

five aims are going to need some redefinition if they are to provide useful

guidelines for Voices. Aim 4 "To provide facilities for any talent in art,

literature and music workers may have", may still be relevant. But it is worth

remembering that Voices is the only "facility" which endured out of a number

provided, which included art and drawing classes and a cinema club. Voices has

persisted because it obviously provides a facility that is needed and because

small group of people are sufficiently interested in its survival to devote a

lot of their time to its publication.

Ben is right

when he says that most of the contributors are too geographically dispersed to

take part in a Manchester workshop. When he says, however, that they are too

"mature to go back to school to learn how it is done", he misses the point of

workshops. It is not a matter of "teacher" and "pupil" relationships-workshops

are a gathering of progressive-minded people who are keen to discuss aspects of

literature, which include literary perspectives, as well as discussion of their

own work and practical problems encountered.

Surely what

is needed is the spread of such workshops all over Britain, with publications

such as Voices serving as "nationals". Voices could provide unity and linkage in

many ways. These could be discussed both by Voices editorial and in the pages of

Voices. One possibility is that Voices might provide a service which published

brief reports from these workshops alongside representative selections of their

work. Manchester workshop could begin by publishing a report of its progress;

and perhaps a small section of Voices could be given over to publishing

selections from its writers.

Finally, Ben

is wrong where he says in his editorial that the only possible criticism that

can be levelled at writings is the "subjective" form, which he sums up in the

phrase "this does nothing or says nothing to me". This seems a pretty hopeless,

even anarchistic thing to say. Not at all in the spirit of the man who has

devoted a great deal of his time to bringing hope and giving guidance in

literary matters. I seem to remember a lecture given by Ben at New Cross Labour

Club which contained the phrase "aping their betters". Ben was, if my memory

serves me, referring to those misguided and aspiring working-class writers who

(for want of guidance and inspiration from teachers and writers of their own

class) tend to emulate writers from the bourgeois literary elite. The purpose of

Voices was not merely to provide an "easy" vehicle for working people which

would be outside the demands of the market, but also to contribute in the job of

building in what amounts to a cultural vacuum. It is about time that some

analysis was attempted as to how far Voices has made its mark in this direction.

Ted Morrison

THE SCOTLAND ROAD WRITERS GROUP

The Scotland

Road group in Liverpool has been going steadily since 1973. It was started by an

outsider, David Evans, a lecturer at Liverpool University, who acts as convener,

but is otherwise made up of working-class people writing for other working-class

people in the community. Weekly workshops are held, and an occasional

publication (also, by coincidence, called Voices). Further information from

David Evans, 1 Wyndcote Road, Liverpool 18.

WHATEVER HAPPENED TO THE GOOD

SAMARITAN?

I watched the

priest from the shield of smiled-at childhood.

He arrived at

the door and six feet of shining black and white nodded at the door and with his

legs slightly apart and hand clasped around a black leather book just in front

of his balls, he addressed and squared up to the door. He leaned forward from

the waist, legs still straight, and his right arm came up as he leaned and his

toilet soaped knuckles rapped coldly on the door and the knock was a knock of

decision, expecting no hesitancy, confident of reply, demanding attention. His

right arm went down to clasp the book to his flies again as his body

straightened and in the seconds before the door opened his neck, just his neck,

twisted as he looked up and down the street benevolently.

Sheepishly Mr

Roach opened the door but left his toe behind it so that it opened only slightly

and then he said, 'Sorry', to the priest and fumbled about as though he was

trying to see what was blocking the door and all the time his grey railwayman's

face was pleading at the priest, jabbering to the priest, and hating the priest.

The priest beamed silently back, waiting for the man to talk himself nervously

silly in the presence of a superior being; patiently waiting for the man to move

his silly toe and let him in.

Mr Roach

leaned his left shoulder against the lobby wall and the door edged back a little

but his railwayman's waistcoated chest barred the way and, more solid now, he

felt his head cooling and so did the big black priest but he beamed silently on.

Suddenly, desperately, the railwayman stopped and listened to himself, this

gibbering, fawning idiot, senseless at his own front door; and he looked at the

priest, the quiet presidential figure, this patronising parasite, and loathed

him and anger welled within him-the stark, tearing anger behind which he could

hide.

The priest

saw it coming as it had come on rare occasions in the past, and, looking over

the man's shoulder, trying to catch a pale wife's eye, he carefully edged his

right leg in between the wall and the door. Mr Roach began to ride on zooming

rays of rage and, enjoying it now, he looked down mock shocked at the charcoal

leg. 'I beg your pardon, Father, but this is my house.' And with outraged

dignity he shoved the priest's leg back off the step. The priest's elbow came up

next and, this pushed away, a piece of shoulder or wavering thigh and gradually

the railwayman was hot again, pushing and shoving at the door as if trying to

close the lid of a small box on some monstrous, black, billowing balloon.

The

neighbours were beginning to crawl out now and let their kids go up the street

so they could go and get them and get, too, a closer look at the action; in

situations like this the advantage is nearly always with the priest-he is used

to such goings-on and, being a superior person, he has no sense of shame.

Invariably as well the wife comes out and drags the man in and makes the priest

a cup of tea and tells him all about the white wine and what it's doing to her

feller. On this occasion though Father Delaney came unstuck: Mrs. Roach, upon

receipt of three brown envelopes from the kids' school, had just soaked her hair

in Lorexane-she wouldn't have come out for Our Lord's sake; and, it being a

November evening, Father Delaney had fortified himself with a half-bottle of

gin.

The gin

didn't help the priest's ballooning balance and after a particularly hefty push,

when he was flapping his arms like a tightrope walker, he thrust into the

doorway the only part of his body he could use-a shiny black arse-and the

railwayman, a Geronimo in his great rage, gave one final heave and the priest,

arms whirling around, was sent crashing head first into the lamp-post from which

he rebounded into the gutter.

The

neighbours went clucking around, gathering in their children and they closed

their doors silently out of frightened respect. Mr Roach defiantly slammed his

door and went back, trembling and fighting with his face, to face his wife.

Father Delaney lay bleeding in the gutter, thinking of the parable of the good

Samaritan, and wondering why nobody came to his aid: "Oh why, my people, have

you forsaken me ?" The thought of the attractions of martyrdom in the streets of

Liverpool slowly became apparent to him. His people watched through rubber

plants and lace curtains. How could they cross the social chasm and have a

superior being dependent on them ? Perhaps that teacher up the road might come

past soon; he could help him. As long as he takes him home, like; we don't want

him coming here tonight

Jimmy McGovern

THE TOP SHELF

A ship in the distance, what a sight,

Whatever made me climb to this height?

Me mam'll kill me, if I don't kill meself,

I'd better get down off this top shelf,

Now if that shelf had broken what would I have done?

I don't know I suppose I'd have run

And if me main had caught me, it wouldn't be nice,

I'd soon know she wasn't made of sugar and spice,

She'd have boxed me ears and made me black and blue, and shouted,

"You're going to pay for it, and it's going to look like new",

I don't know though it was great up there,

Looking out across the Mersey to New Brighton fair,

I think I'll climb up and have one last decko,

I'll climb on the fridge first, and stand on the echo,

I've got to do that so I won't make a mark,

If me main sees it she'll have one big nark,

I'm nearly there, not far to go,

The first shelf, the top shelf,

Ooh, I've put me hand in some dough,

Never mind I'm here,

And the day's nice and clear,

On top of Tate's I can see iron rails

And right over there I can see the hills of Wales

Ay up, the shelf's going, I'll be damned,

Aaaah, I've hurt me bloody hand,

And me foots stuck in the best pan,

"er hello mam".

Chris Darwin

I

FOUGHT NORMAN SNOW

The early

sixties were a good time to be a Scouse in London. All of a sudden, it was very

fashionable to be able to say you were from Liverpool, and I even knew one or

two Mickey Mousers that were from Leeds. But myself and a few mates of mine were

the genuine article and we wouldn't let anyone else into the act, even if they

came from Birkenhead. And of course, it was all down to the fact, that four lads

from Liverpool had made some hit records. The Beatles they were called.

Remember? One of my mates was supposed to be a cousin of John Lennon, another

was allegedly the cousin of Paul McCartney and me, with my hooter had to be a

relation of Ringo's. Funny enough no one claimed to be related to George

Harrison. Funny that.

Anyway,

instead of us just being some lads from up North somewhere, we were more easily

accepted as being someone. Or nearly, anyway. And as a consequence we met some

very interesting people. But one of the most interesting people I met was an

ex-professional boxer named Charley Burton. You most probably have never heard

of Charley, even if you were a fight fan. But the same guy had three hundred and

sixty four fights, professional, from bantamweight to middleweight and never got

near a title fight. But of course that was in the hard times, in the 'twenties

and 'thirties, when most fellows were just fighting to live.

I'll never

forget the day I hurt him though. We were hanging around the betting shop in

Fulham that he ran, which had become a habit with us because of the characters

that popped in and out, and the conversation, which was mostly about some sort

of villainy or other. Or it would be about boxing. And this of course Charley

loved. He would go through all kinds of moves, jabs, hooks, blocks, feints, the

lot: and generally his opponents always ended on the canvas, and Charley was the

hero of Fulham.

But this day

I interrupted him. I said:

"All right Charley, you've had all this number of

fights, but who have you fought who was any one?"

This got a

bit of a laugh from my mates, but Charley just smiled, took his cigar out of his

mouth, looked at the tip for a moment or two and said quietly, but with some

pride:

"I fought Norman Snow”

This of

course, made some of the boys near collapse with laughter. "Who the hell was

Norman Snow ?" gasped out Tony, between laughs. Now it just so happened that I

had that week's Boxing News in my pocket, and funny enough it had Norman Snow's

record in it, which covered a number of years and hundreds of fights. So I could

afford to be a bit knowing when I said to Tony:

"Wait a minute. He was a good

light and welter before the war. He must have been a good 'un, he even fought

Ernie Roderick".

Now Charley

started looking pleased again, because he had become more than a little annoyed

when the chaps started laughing and Mickey-taking. But I was waiting my

opportunity for a right giggle, because I was sure Charley's name was not

mentioned in Snow's record, which you will remember I had in my pocket all the

time. So I got Charley to talk about Norman Snow and he went off like a good

'un. Snow would do this and Snow would do that, but Charley blocked this and

blocked that and sneaked a few of his own punches in. He talked a great fight

did Charley.

So after he'd

got his audience back and he was happy with the centre of the stage, I, like a

louse, pulled out my copy of the Boxing News. "Well here's a coincidence" I said

"Norman Snow's record is in here". I was watching Charley at the time, thinking

I would catch a guilty look about him. But no, he was carrying it through. "Come

on I'll sort the fight out" he said. Well he looked and we looked, but sure

enough I was right.

Charley

wasn't mentioned. I started to laugh, seeing the look of confusion on Charley's

face and that was the signal for everyone in the betting shop to start laughing

and cat-calling old Charley, calling him a right old storyteller, but not

exactly those terms. After I'd had my laugh, I happened to catch the look on

Charley's face and I suddenly realised, he was Old Charley, and I'd spoiled his

stories and made him the butt of cowboys who wouldn't have said boo to him in

the old days. So I said "Listen Charley, take no notice of that, there could be

a misprint and anyway, most of these old records are incomplete. They're always

making mistakes in them. We'll get in touch with Tim Riley the editor. He can

put a correction in". I was saying all this to try to make it right for Charley.

But I could see it wasn't working. The poor old bastard was near crying, and I

felt sick about it all, as well. I felt that all I had to do was keep that paper

in my pocket and Charley wouldn't feel like this. So after making a few more

sympathetic noises, I made an excuse and left. The boys were still laughing.

I stayed away

from the betting shop for a few weeks, knocking around the West End with some of

the other scallywags. But eventually, I made my way back to Fulham to see how

Charley was getting on. Surprisingly, he gave me a big hello and made quite a

fuss of me, which to be honest, made me feel more guilty. So I hung around for a

while chatting to him, but the talk didn't get to boxing. Just then, three

fellows came in, and you could see straightaway it was trouble. The biggest

started to slag Charley something terrible over some bet he claimed he had. In

no time words had turned to blows. The big fellow threw a punch that Charley

slipped easily, but the other two tried to grab hold of Charley, and so I even

though I'm allergic to violence (I come out all cuts and bruises) had to make

myself busy. I gave one fellow a crack on the chin and he went down, not

surprising really. I picked on the smallest and he didn't see me anyway.

Meanwhile, Charley is giving a really good account of himself with the big

fellow so the other fellow turns on me. I tried to throw the head in on him, but

would you believe, he beat me to it, and butted me. I don't know what was hurt

more, my nose or my pride, but it was my nose that was bleeding. Fancy a Scouse

losing at the nanny goat. And to a Cockney as well.

When I came

to, Charley had knocked out the big fellow and even had the fellow who done me

on the floor. I heard Charley say to him "You'd better be able to use that" then

the geezer jumps up and punches Charley in the stomach. I thought he had punched

him. Then the geezer runs out, and I'm after him. I chased him down Charleville

Road and along North End Road but I lost him going towards Fulham Broadway,

which the way it turned out was lucky for me.

When I got

back to the shop, the other two hard cases had disappeared, but Charley was

still on the floor. And old Charley really looked old. I knelt down by him and I

saw all the blood from his stomach, and I realised it wasn't a punch that had

put him down. It was a knife. He opened his eyes just then and said:

"I really

did fight Norman Snow you know".

"I know" I lied. "I wrote to Tim Riley".

"Good

kid" he said. Then he died.

A few weeks

later, I was in a pub next door to the Old Vic's stage door, and an actor friend

of mine who I was having a pint with introduced me to a chap. He said he was a

producer. He had one of those superior attitudes and he needled me straightaway.

"Oh, you're from Liverpool are you ?" he said, speaking so far back his voice

was coming from behind him. "I suppose you're a great friend of John, Paul and Ringo ?" I felt like giving him a belt. Even he didn't mention George.

"No" I

said. "I never knew them. But I knew a fellow who fought Norman Snow".

Ed Barrett

POET FAILED

I remember how I tried to be a poet,

and tour all the folk clubs with me verse,

but every time I tried to get a gimmick,

somehow all me poetry got worse.

I remember very well just how it started,

I copied another poet, such a sin,

'Cause no sooner had I eaten me banana,

than the landlady she trips up on the skin.

So then I thought that I would buy a doggy,

and call it Mr Entwistle by name,

But when I got him home the budgie ate him,

and another good idea went down the drain.

A bloke I know then sold me this stuffed parrot,

there's a cleaning bill resultant of his wit,

£4.69 for bar-room curtains,

'cause it flew up there and covered them in Parrot seed,

The next time I went into a folk club,

I found reciting in bare feet just caused no shocks,

The only rumbles caused that night were by me,

Some bastard pissed off with me shoes and socks.

So I thought it time I found a new vocation,

the singers in this club wouldn't have a hope,

so this afternoon I bought a brand new Gibson,

and then fell down at the bus stop and it broke!

N Clinton

RESETTLEMENT

It couldn't be worse than here

or so we thought,

the hunger, the hostile glances,

the endless waiting

for nothing.

so we saved up for our train fare

our train tickets

to Auschwitz.

They crowded us all into cattle-trucks,

no room to move, no water,

the infants wailing,

the old slowly fading away,

unable to breathe in that hell on wheels.

Father was lucky

he died on the journey

it made me numb with loneliness

but later

I knew it was all for the best.

When we were unloaded

I could hardly walk

the air

tasted so fresh, so bitter-sweet.

RESETTLEMENT

It couldn't be worse than here

or so we thought,

the hunger, the hostile glances,

the endless waiting

for nothing.

so we saved up for our train fare

our train tickets

to Auschwitz.

They crowded us all into cattle-trucks,

no room to move, no water,

the infants wailing,

the old slowly fading away,

unable to breathe in that hell on wheels.

Father was lucky

he died on the journey

it made me numb with loneliness

but later

I knew it was all for the best.

When we were unloaded

I could hardly walk

the air

tasted so fresh, so bitter-sweet.

We were surrounded

by men in striped uniforms

like sleepwalkers in grotesque pyjamas;

I heard two of them joking in Polish

and childlike

smiled in happiness

I asked them

Sirs...where am I?

where have I come to?

They laughed at my naivete

and answered

- The centre of Hell.

There was nightmare in their unshaven smiles

you will leave by the chimney

my child

smell the ashes in the air

the sweet smell of burning

in the morning air

The German officer jokingly shouted

- sheep to the left

goats to the right

He ruffled a child's hair

as he pushed her

to the right

- those on the right will be dealt with first

shower and delousing...

those on the left will have to wait

He sounded like a gentleman

everybody trusted him.

He wasn't kidding

the next time we saw them

those of the right,

mainly women, old men and children,

I lost my faith in Daniel.

They were a pyramid of warm corpses,

fingers in eyes,

elbows in mouths

all struggling to reach the vent,

fighting each other to reach the airhole

through which, ironically enough,

the poison pellets dropped

our job?

to disentangle them.

We waited all right,

we waited for the allies,

there was no other hope

Had we not cried to God,

Lord of Righteousness

see what thy enemies do to thy people.

Had we not been mocked by an empty sky?

And now ? Thirty years after ... I am still waiting...

for what?

Resettlement.

We were surrounded

by men in striped uniforms

like sleepwalkers in grotesque pyjamas;

I heard two of them joking in Polish

and childlike

smiled in happiness

I asked them

Sirs...where am I?

where have I come to?

They laughed at my naivete

and answered

- The centre of Hell.

There was nightmare in their unshaven smiles

you will leave by the chimney

my child

smell the ashes in the air

the sweet smell of burning

in the morning air

The German officer jokingly shouted

- sheep to the left

goats to the right

He ruffled a child's hair

as he pushed her

to the right

- those on the right will be dealt with first

shower and delousing...

those on the left will have to wait

He sounded like a gentleman

everybody trusted him.

He wasn't kidding

the next time we saw them

those of the right,

mainly women, old men and children,

I lost my faith in Daniel.

They were a pyramid of warm corpses,

fingers in eyes,

elbows in mouths

all struggling to reach the vent,

fighting each other to reach the airhole

through which, ironically enough,

the poison pellets dropped

our job?

to disentangle them.

We waited all right,

we waited for the allies,

there was no other hope

Had we not cried to God,

Lord of Righteousness

see what thy enemies do to thy people.

Had we not been mocked by an empty sky?

And now ? Thirty years after ... I am still waiting...

for what?

Resettlement.

QUNEITRA I'M NOT ONE OF YOUR MANY SONS

The first light of dawn doesn't dry the dew from the roses.

The butterfly rests no more on the flowering apple tree.

The wind smells no longer of jasmine

Where the fountain was, the crowded cafes

Now ruins, barbed wire.

The robin clutches a twisted piece of iron lost without its voice

Where are the vegetable carts from the nearby valley ?

Where are the smiling children scurrying like ants

In the school yard?

Where is the young wife giving birth?

Where the Tiberian women selling country cheese

And thick yoghurt?

The aroma of broiling liver and green onions, the yellow

Of the bananas the red of the apples?

Where is all this ?

Mine is not a song, nor even a lament

Perhaps just a catch in my throat at the sight of Quneitra.

I climbed a precarious minaret hoping to see a roof;

Only tortured metal and suffocated trees.

My comrade; I would like you to see all of this

Any doubts you might have on Zionism and its principles would vanish

Quneitra

There is a pure sound to your name

Like the streams of Golan

A flower's name, the flower of the high plateau.

The name of a woman

Quneitra

I am not one of your many sons, nor your lover

Only the son of a far-away shepherd

A foreigner who loves you.

You are not dead

Your streets will echo with life.

PIE IN THE SKY

We the undersigned

being of sound mind

declare our belief

in life after death.

It matters not

we cannot locate

the exact spot

where we shall meet,

For there can be no

living or loving,

taking or giving

but thinking makes

it so.

Bill Eburn

TWO MINUTES

(A Poem for Jubilee Year)

Firstly the grave announcements,

and then

Suitably Solemn Musick on the airwaves.

The newsreels showed

a young heiress's dash by aeroplane

from one of those warmer, more congenial spots,

favoured by English royals,

when duty calls,

around the onset of each native winter.

Then the publicity got under way-

the morbid, lush magnificence of the funeral;

that catafalque (funny word, one recollects)

with queues of curious, acquiescent mourners.

One must admit to being 'strangely stirred'-

and who could not- given the machinations of a code

with thirteen hundred years' experience dispensing intellect-defying dope?

But what sticks in the memory the most,

is the statutory nationwide two minutes.

Myself at the time was gainfully employed,

boosting the national matzo-bread production.

My hands were stiff and sore with slinging trays,

my eyes like chapel hat pegs

through gawping at the silly squares of dough,

trundling by the thousand through the oven.

Almost eleven-the manager raised his hand;

the foreman threw a switch;

the belts stopped turning-

and fifty loyal matzo-making commoners

(trying not to look self-conscious),

came rigidly and solemnly to attention-

including yours truly-

snatching a surreptitious lick at blistered fingers,

and feeling rather glad the king was dead-

if only for two minutes.

Derek Lee

JUBILEE

I'd of forgot

all about it if it wasn't for Phil and Charlie. They operate the borers on

either side of mine.It was during the tea break on Monday when it came to light.

Phil says to me. Here Lobby" they call me Lobby because of my limp. He says:

"Here Lobby, it's your Silver Jubilee next week, ain't it ?" I said: "You what

?" and Charlie says: "Next week you'll have been with the firm for 25 years".

And then I thought: "Bloody hell, he's right. 25 years with the old firm. I

suppose that's something to be proud of. It's gone so bloody quick I've hardly

noticed. 25 years, bloody hell!"I remember the day I first got the job. I'd had

my name down for ages with the personnel office. The lads down at the pub used

to pull my leg about it summat awful, when I used to brag that one day I'd be

working at Dunkers.

"You'll never

get in there." Old Ted used to say. And Albert Foster used to laugh and say that

I'd be waiting ages for 'dead man's shoes'. But I got the last laugh on them,

when old George Tarbury got sucked into the machine and mangled to death. I got

the letter on the Friday, as he got sucked in on the Tuesday. "Can you start on

Monday ?" it said. I was on the dole at the time, so I thought "Not half !" And

I was down at the personnel office 7.30 sharp on the Monday morning.

It was damn

good money here in those days. It's good money now, I think, but it doesn't seem

to go as far somehow. It was worth getting a job, and keeping it, in those days.

Not like now. You got bugger all on the dole them days. Bloody hell, look at it

now ! Them lazy dossers down at the Dog and Crutch get almost as much as I get

for working forty hours. And all they do is sit in the vault swilling beer all

dinnertime, and then shuffle down to the bookies when the pub shuts.

Everything's different now though. The whole bloody country seems to be going to

the dogs. What with the trade unions dictating everything, and the Pakistanis

flooding the country, and the Chinese buying up all the chip shops. Old Winston

would of stopped their gallup if he'd have still been around. Aye, Old Winnie

was the best Prime Minister this country ever had. Not like the bugger that came

after him, that cross-eyed MacMillan geezer. Old Winnie wouldn't have gone round

giving all them darkies independence., like old cross-eyed MacMillan did. Bloody

hell, not half he wouldn't ! The buggar gave them independence, and the next

thing you knew they were swarming over here snapping up all the plum jobs. Old

Winnie would of kept them right out. He'd of restricted their numbers. He

understood the ordinary bloke did old Winnie. That was because he was an

ordinary bloke himself.

We've had a

few darkies in here at Dunkers over the years. I've seem 'em come, and I've seem

'em go. They never stuck it long. The old boring machine is too complex for the

average darkie to handle. They can't get used to it. None of them would admit it

though. They were proud sods, some of 'em. They'd never admit that they weren't

as clever as 'old whitey'. They'd all come up with some lame old excuse for

leaving, like "The money's no good" or "The conditions are not up to scratch".

Well I’ve been here 25 years, and Phil and Charlie have been here even longer

and we see nothing wrong with the money and conditions. Well, not much anyway.

Aye, I've

seen some changes in my twenty five years. I suppose everything changes over the

years though. Funny thing, my machine's never changed in all that time and it's

still as reliable as ever. Well, nearly. I've seen a

bit of bother in my time too. Like that time when they tried to get the union

into the place. Bloody long haired sod it was who tried to get 'em in. A right

little shitstirrer he was. Always trying to wind the men up. Always causing

discon-bloody-tent. Old Greenie the General Foreman soon had him out on his arse

though. The bloody union was taking on summat when they took on old Greenie. He

was in that Korean dust up. He fixed the bloody commies over there. And he'd fix

'em over here too, if he got half the chance. They could do with a few like old

Greenie up in bloody parliament. Tough as rocking-horse shit he is, and twice as

combustible. The union put a bloody picket line outside the gates for a few

weeks, after they fired the long-haired 'un and a couple of his shit-stirring

mates. But we took no bloody notice of 'em. We let em shout and rant, and stew

in their own juice for a few weeks. They soon got fed up of it, and buggared off

somewhere else to stir up their shit. That's the way to deal with unions, just

ignore the bleeders. They soon sling their hook when they know they're up

against someone whose forgot more than they'll ever know about bloody work.

Phil and

Charlie are trying to arrange a bit of a do for me in the canteen next Friday.

That's if the management will allow it. They've both been at Dunkers longer than

me. Charlie's been here since the place opened up in the 'thirties. He started

in the loading bay, and then he got a chance of a job on the borer and he

snapped it up. It was only a couple of coppers more a week, but it's a trade,

isn't it ? Phil's been here since the start of the war. When he heard that war

was about to break out he rushed down here and told 'em that he was a skilled

vertical borer. It was a reserved occupation at the time. Took a chance he did,

but he picked the job up soon enough, without anyone knowing the difference. You

can soon pick it up though, if you've anything about you. You can't go so far

wrong on a Stevenson & Whipple's vertical. I often wonder how old George managed

to get himself sucked into the buggar. Charlie said that one minute he was

standing there large as life, next minute he hears a scream and there he is as

dead as a doornail. Still I suppose all these things are sent to try us. One

man's misfortune is another man's gain.

You don't get

operators like Phil and Charlie anymore. I reckon they cracked the bloody mould

when they poured them two out. All we seem to get nowadays are young kids. Bits

of kids, straight from school. You try to get 'em a good training, but they

never seem to stay long enough. When they get to 17, old Greenie sees 'em off.

Charlie reckons it's something to do with the management wanting to give the new

school leavers a chance.

A lot of

people say that I'll be the last fellah to get 25 years in here. They say the

place'll be shut down in a year or two. But they've been saying that for years.

The Foremen keep telling us that the firm's losing money. But they've been

saying that for years too. Charlie says that the firm's been losing money ever

since he started here. I reckon they only keep saying it so that they can keep

our wage rises down to a minimum.

I'll tell you

what's a bloody funny co-incidence though. Me celebrating my 25 years in the

same week as her Majesty celebrates hers. Still, when I look back at it, she got

crowned the same week as I started here. So that explains it I suppose. Aye, I

copped for a day's paid holiday the same week as I started. It fell lucky for

me, didn't it ? And now, 25 years later, I'm copping for another day's paid

holiday. It makes you feel good inside to be living in a civilised country,

doesn't it?

Mike Rowe

RENT STRIKE

(to my mother)

Last ones to pay!

The rent-collector hasn't even the grace to snigger.

Now, thanks to a stand, struggle-by-struggle lies undone.

Paying at the end was less of a sacrifice than not paying

at the beginning.

Like someone fleeing a fire, you carried a prized

possession,

But threw it away to help the others get out:

Last ones to pay ! That's no blemish,

It's a bloody banner.

John Koziol

It might have been

acceptable for those piss‑artists in the Rails Branch to congregate in the Royal

Oak disguised as a Union Meeting, but the Town's Branch of the Communist Party

of Great Britain insisted on strict legality. Stanier wrote formally to the

landlord on CPGB red letterheaded notepaper and wasn't all that surprised,

three weeks later, to get a reply regretting that the room couldn't be made

available to 'extreme political groups of an anti‑democratic persuasion'. It

smelled of head office public relations. Anti‑democratic! Hadn't these people

read The British Road?

The decision was regretted

also by 'Hollowlegs' Ernie Barlow and his fellow foundryman Harry Horsefield.

They both suffered from an interesting medical condition; neither could get to

sleep at night unless he had at least five pints. Just fancy jugging it during

the meeting like those lucky bastards in the Rails Branch instead of having to

prod the business to a sudden close at nine o'clock so they could get over the

road into the Cock and Trumpet. But even that problem was mitigated by the fact

that Barlow was the Chairman. He suspected Jud had sabotaged the whole thing

just to slow them down. Anyway the Royal Oak was Tetley's and the required dose

of that gnat's piss was nearer seven or eight pints.

So the Town's Branch met

in the Coop at three pounds a month and its conscience was clear. It was a

strange little room, cream and green like a hospital or a nick, no windows, one

wall lined with mirrors, an upright piano in the corner and an Ascot gas water

heater which gurgled and dripped into a massive sink. Over a row of coathangers

at the far end was a notice which read: PERSONS FOUND DAMAGING THIS DRESSING

ROOM WILL BE BANNED FROM THE PREMISES. The Party literature was on a small

table near the door with a McTavish Shortbread Biscuit tin opened ready for the

cash.

It was a well attended

meeting. Eight people sat on two rows of plywood and steel tube stacking chairs

facing the warning notice. Jud Stanier, as Secretary, sat alongside Barlow

behind a formica topped table facing the rank and file, the piano and the Ascot

heater. A thin young lad with long hair and a single earring sat down after

making a lucid report.

'Well, you've heard what

Comrade Stelfox has had to say about the sit-in at Greenings Wire Works. Any

questions?' No harm in getting a discussion going thought Ernie. Only one more

item on the agenda and it's still only half eight.

'What's the chance of it being

made official ?' Ted Winter, schoolteacher retired, stooping, cord jacket, NHS

hornrims; the u shape of his pipe mated with the n shape of his nose.

'Support's one hundred per

cent' replied Arthur. 'Picket lines aren't being crossed, lorries aren't coming

and going; the area rep's coming down to see us tomorrow.'

'Who is the rep these days?'

'Matthews'.

'That twat!' A significant

look passed from Ernie to Jud. 'He used to work at your place didn't he ?'

'Best warn the lads when you

get back Arthur' said Stanier. 'Matthews is as right‑wing as they come. He

used to spout a lot when he was on the shop floor but as soon as he got that

full‑time Union job he turned right round. He'll try and bamboozle you into

going back, pending discussions with the management.' A ripple of grim laughter

went round the room as Jud invested the cliche with his heaviest irony. 'Stick

out for something concrete.'

'Well Comrade Secretary I move

we send a message of solidarity and support to the lads occupying Greenings and

a donation of...' Ernie glanced at Ted, the Treasurer, 'Could we go to a fiver

Ted?'

'Better make it three.'

'Three pounds.'

'Seconded.' said Stanier.

'All in favour ?' Every hand

rose. 'You can write the letter Jud, on Party notepaper. They're bound to have

a noticeboard they can pin it up on. And if it hasn't been made official yet

they won't be getting strike pay. Now then, item six: Morning Star sales.'

An uneasy silence

descended. Some looked into the mirrors in an attempt to detach themselves.

Fleet, who'd only been a Party member for two months concentrated hard on his

toecaps and noticed a split stitch and a faint smear of dogshit on the welt.

The Ascot gurgled. Ted smiled inwardly and folded his arms. It certainly

wasn't like this in the forties when he was working in the Hackney Branch. They

didn't ask you to sell lit in those days. They just dumped a pile in your arms

and came back the next day for the money. How many cubic feet had he shovelled

onto the fire and paid for out of his own pocket? No doubt about it, things were

getting better all the time. Ernie gestured Stanier into the firing line.

'As you know Comrades next

year I'll be standing for election to the Town Council. We've discussed this

matter at Branch Committee and decided that it would be a good idea to combine

preparations for the election with a Star Sales campaign to cover the whole of

the Fairfield Ward. George has run off copies of the street map on the Party

Xerox machine which we keep in Carlisle's offices (laughter) and we've divided

the whole area up into sections. Here's how I see it working.' Jud was on his

feet now. The Branch gave him their respectful attention. His energy was

already starting to get to them like a life‑giving drip feed.

'First we go round with this

leaflet,' He held it up, 'which explains what the Star is, how it's different

from the millionaire‑owned capitalist press and how, because of its financial

independence it's able to fight consistently for progressive policies.' The wail

of a band warming up filtered through the wall. Sometimes the large hall next

door was hired out for choir practices.

'Having got people interested

we go round again the following night with the Star itself. Not only do we sell

the Star but we also make contact with every voter in that ward, note who's

sympathetic and argue for the policies of the Party. To any of you, especially

you younger ones, like Arthur and Frank, who's never been on the knocker before,

let me tell you it's a great experience. And don't imagine it's a waste of

time! Remember we're not going to get into power in this country by storming the

Houses of Parliament or shooting coppers in the street. And trade union

activity alone isn't enough either, 26 proved that. No Comrades!' The bright

brassy beat of Onward Christian Soldiers bored through the wall. Stanier

grinned: 'And the bloody Sally Army won't be much use either! (laughter) It's

not soup kitchens this country needs, it's socialism! '

Ted was really enjoying

himself. The spectacle of Stanier in full flow was an education. He had stuck

with the Party through it all: the Fascist Pact, Tito, Twentieth Congress,

Hungary, Czecho. Total trust; total dedication. Ted, on the other hand, had

dropped out in 56 and come back in 60. That was in London but Stanier knew

because he'd been on the North West District Committee which had considered his

reapplication in Manchester. Could Jud ever forget that betrayal?

'Class‑consciousness ! That's

what it's all about. We're going to get there by changing the way people

think. And it's not brain washing, or putting one over on them, that's the

beauty of it ! It's simply a matter of telling them the truth, opening their

eyes, showing up the real nature of bourgeois society, how it depends on

exploitation and how it generates unemployment and poverty.'

Ernie was beginning to get

impatient. This bloody demagoging was all right on the streets or in the pub

but here, among the steel‑hardened cadres of the Town branch it was verging on

an insult to the membership's intelligence. Besides, time was passing. Still

the young lads seemed to be lapping it up.

'It's the hardest task in the

world! Remember what Lenin said to the woman who asked him how she could help

the revolution. When he found out she came from England he told her to go back

and work there, right in the heart of capitalism. There was no more important

job to be done. Soon we'll be moving into a period of intensifying class

struggle with problems we've not seen since the thirties. People are going to

be looking for answers. They won't find the answers on the telly Comrades And

they won't find them in the Daily Mirror! They'll find those answers in the only

independent newspaper of the working‑class, the only newspaper which isn't

spewing out capitalist propaganda, the Morning Star! ... Providing of course

they know the Morning Star exists.'

Ernie took off his watch

and pushed it along the table in front of Jud. The branch was no longer staring

at its shoes or glancing into the mirrors; it was gripped by Stanier's

impassioned rhetoric and the big eyes bulging out of a face like a piece of

mauve coloured shrapnel. He glanced down at the watch.

'So let's show 'em that the

Star exists, and that the Communist Party exists. You've not joined to talk

about revolution in Coop Meeting Rooms; We could do that till we're blue in the

face and the ruling class wouldn't give a toss. No! We're all members of this

Party because we want to FIGHT for the working‑class. And that's where we've

got to do it, out there, on the streets, ON THE KNOCKER ! So let's get stuck in

and DO IT!' He sat down. It was as if a power station turbine had been shut

off; a stunning, buzzing silence.

Barlow strapped his watch back

on.

'Any volunteers for next

Wednesday and Thursday ?' Ted gestured.

'Count me in' said Horsefield.

'I'll be there if I'm not on

picket duty' said Arthur. George Bender stuck his hand up; even old Bill Vine.

'Now then Billy' said Stanier,

'You're in no condition to go tramping round the streets with your ticker the

state it's in.'

'Just thought if you were

short‑handed.'

'You do enough for the Star

already. Bloody hell! You're collecting a fiver a week already aren't you?'

'It's not so bad on the bike

in the daytime. Anyroad, what about you Jud? 'Y'old bugger ! You won't be

running any races with what you've had.' Stanier had been badly gassed at work

years ago; his lungs were still affected.

'Reckon they might need me and

Ted in case they run into any of these young Trots.' Ernie referred to a diary.

'I won't be able to make it

Thursday. Got a Union meeting.'

'I'm on two ten that week'

said Brian Burns.

Joe Cornelia spoke. He

flattered speakers who moved him by repeating their ideas from the floor. His

gift for redundant amplification resulted in summaries longer than the original

speech. This bored the majority, amused Ted and struck terror into the heart of

Barlow.

'I'd like to fully endorse the

... er ... sentiments so forcefully and correctly expressed by Comrade Secretary

Stanier. It is ... vitally important that we increase the sales of the Morning

Star, the only paper which continually pursues ... er ... progressive policies

... on behalf of the working‑class. As brother Jud ... er ... Comrade Jud has

rightly pointed out, what this country needs is soup kitchens not socialism ...

er ... socialism not soup kitchens I mean to say, socialism not soup kitchens

Comrades and it is therefore our duty ... er ... as members of the Communist

Party, to try and raise ... er'

'Think you'll be able to make

it Joe?' Ernie ducked in under a gap in what promised to be a massive

structure. 'Next Thursday?' he added quickly in case some of the branch

imagined he meant the end of the speech.

'Well ... er ... I was just

coming to that point Comrade Chairman ... you see, unfortunately, I'll be ... er

... indisposed ... yes, indisposed on that particular evening ... er... and on

the one previous to it ... and even on the subsequent evening too... on account

of... er ... on account of...... interior decorating.' Ted skilfully managed to

turn a laugh into a cough. Ernie didn't try to restrain a grin:

'You'll just have to settle

for raising the class‑consciousness of the missus then Joe. Still you've done

your share in the past. Now then, any more?'

Fleet's dread of standing on a

doorstep asking strangers to part with eight p was in conflict with the moral

sense aroused by Stanier's speech. Finally he put up his hand.

'Good on yer Frank !' Stanier

beamed. Two months in the Party was a tricky time. Push them too hard and they

back off in fright; leave them alone and they fade away out of boredom. Got to

stir their conscience, that's what made them join in the first place.

'Well! That should be a real

good turn out. Six! We'll meet on the Rope and Anchor car park at half past

seven on Wednesday; leaflet three hundred houses, that'll take no time at all

with six of us out, then go back again on Thursday with thirty six Stars. I'll

organise them. All right?' He glanced at Ernie who looked at his watch.

'Any other business?' A throat

cleared menacingly. 'Right! Meeting closed!'

'Collection for the room!'

shouted Stanier over the noise of scraping chairs. They jostled out in a wave.

Ted recalled those special meetings in Hackney when they left at minute

intervals in ones in case the police were watching: things were getting better

all the time.

On the car park they

sorted out the maps in the back of Ted's Volkswagon Caravanette. Horsefield and

Bender were going to do Austral and Hilltop, Stanier and Arthur took Corporation

Crescent and Bibby Avenue while Ted and Fleet got Poplars and Grasmere. Stanier

gave his last instructions:

'You and Frank better stick

together Ted, while it's his first time. The rest of us will do opposite sides

as usual. And don't bother with those pensioners maisonettes at the end of

Poplars. They won't answer the door after dark and even if they do they won't

feel like parting with eight p on their screw. Meet back in the Rope when

you've finished.'

'Last one in buys a round'

said Horsefield. He and Bender were an unlikely pair. Harry was built like a

barrel. Ten years of humping ninety pound moulding boxes and ladles of molten

iron had given him a massive upper torso which merged into a well‑developed beer

gut, a product of ten years humping pint glasses. At twenty six he'd been in

the Party since he came out of his time. Barlow was his god; he'd taught him

the trade and politics at the same time. The only trouble with Harry on the

knocker was his short‑fuse temper. Bender was nearer forty, a draughtsman at

Carlisle's and a specimen of an almost extinct breed; the Party dandy. Visiting

speakers from District were shocked seeing Bender for the first time in a room

full of open necks, anoraks and donkey jackets. There he'd sit, immaculate;

tie, clean shirt, creased pants, perhaps even a white handkerchief sticking out

of his top pocket. This improper dress had got him the reputation of being

something of a shallow waster; that and his weird wit. Apart from the most

exclusive bond of all, a Party card, that's what he had in common with

Horsefield; they were both jokers. Stanier had reservations about the pair of

them; they seemed to enjoy themselves a bit too much. As they started off down

either side of the street, Harry shouted: 'Proletarians of the world unite!' to

which Bender shouted back: 'All Power to the Soviets!'

Stanier and Arthur got

together before the assault on Bibby.

'Do the odd numbers Arthur.

You'll probably get to the end before I do at the rate I walk these days so

start back on the evens till you get to me. Don't forget to make a note of the

numbers where you sell a Star and if you get talking try and steer the

conversation round to the Tenants' Action Committee and mention that it's

fighting the recent rent rise. Tell them I'm Chairman and if they're interested

in joining we have meetings in the Community Centre every Wednesday on the first

week in the month. Got that? Let's get going.'

It wasn't long before they

were dealing with that old, well‑roasted chestnut: Moscow Gold. Horsefield had

sized up his interrogator as a miserable little Tory anyway. A painted

cartwheel up against the wall and a brass coachlamp near the door suggested he'd

bought his house off the Corporation years ago. Up the drive was a trailer with

a boat on it. Stanier would probably have tried to reason with him but as far

as Harry was concerned it was a big waste of time. He thrust his face close to

the man on the doorstep, looked up and down the street conspiratorially and

raised his voice to compete with Coronation Street belting out of a 22 inch

colour telly:

'Course we get subsidies from

Russia' he said, 'See this donkey jacket?' he tugged the lapel, 'Made in

Leningrad. Specially flown over for us lads selling papers in the streets.

Never mind the paper though. I can see you're a man who knows how to live' he

nodded at the coachlamp 'Hows about a nice tin of imported black market caviare?'

Backing off from Horsefield's threatening bulk he slammed the door.

With Stanier it was just

like turning on a tape recorder. He was a real politician; serious but calm:

'Well I really don't know

where you get your information from my friend, or what kind of newspapers you

read, but that kind of lie is typical of the anti‑working‑class propaganda put

out by the mass media in this country. The Party has never got a penny from the

Soviet Union, nor would it accept it if it was offered. This newspaper here,'

he pointed to the relevant section of the front page, 'survives on the

contributions of its readers.' He paused to let this extraordinary fact sink

in. 'The readers of this newspaper contribute seven thousand pounds a month

just to keep it going. That's how important they think it is. And why do they

do that? I'll tell you why......'

Ted fielded the question in

much the same way but Fleet was puzzled.

'Where do they get these

bloody ideas from Ted? You only have to be in the Party a couple of weeks to

realise the whole thing's run on a shoestring. Christ! Only in the last

bulletin it mentioned that District were having their phone cut off again

because they couldn't pay the bill.'

'Well Frank, there is a

historical basis' Ted wouldn't have gone into this with those ignoramuses on the

doorstep but Fleet's understanding was at a higher level.

'In the early days the Party

was subsidised by the Soviet Union, well, Comintern to be precise. In 1925

alone it got well over fourteen thousand pounds. The press got hold of it

because the police raided Party headquarters that year and spilled the beans.

People have got long memories, and even though the details have slipped into

obscurity some kind of folk knowledge has persisted.'

'It could have been a frame

up.' Fleet seized on the easy answer like an old pro. Ted laughed.

'Now you're talking like Jud.

Course if you wanted to be strictly legalistic you might say that Comintern was

an independent, international organisation financed in theory by its

member‑parties. However,' The well‑oiled academic machine was now cranking

inexorably....... it would certainly be completely wrong to deny that the bulk

of its funds came from the Russian Party.' While Fleet absorbed the information

Ted pushed open the next gate and went on:

'Nevertheless I see

nothing morally reprehensible in all that. And the present day reality is that

the British Party is completely self‑supporting.' He nodded at the knocker, 'You

can do this one.'

While Fleet knocked

apprehensively Ted booted back a ball which had come rolling down the path. 'Up

the reds !' he shouted, 'Who are you then? Kevin Keegan?' A boy in a red

sweatshirt appeared:

'Kevin Arseholes ! We're all

United here! What yer sellin' then?'

Bender was, as usual on these

occasions, playing a blinder. His smart turn‑out and classless accent really

cut ice on these Corpy estates. People opened their doors thinking he was some

kind of superior clubman. Then after noticing he wasn't wearing bike clips,

imagined he was from the NAB or even the Town Hall. They felt proud to have him

on the doorstep and were intrigued by his peculiar newspaper. He was soon

chasing across to Horsefield for a refill. 'Got any left ?' he inquired with

ironic innocence, 'Give us a few, I've sold all mine.'

'You've not flogged them many

Bender,' said Harry, 'I've been watching. You've been sticking 'em down grids.'

'Give 'em here you bloody

clod! Down grids! Come with me next time Harry, see how it's done. Hey!

Should've seen what opened the door at number twenty four!' He cupped his hands

in front of him. 'Tits like coconuts!'

'They peck holes in milk

bottle tops too.' said Horsefield dismissively.

'No kiddin' I'm going back next

week with Marxism Today.'

'I'll have to report this to

Comrade Stanier Bender. You're just using the Party to further your own end.'

'Aye, somehow I just can't get

rid of these vestiges of bourgeois individualism.'

At half past eight Stanier was

arguing about the Wall with a man who had done his National Service in Berlin.

'Surely every state has the

right to protect its sovereignty by border controls?'

'Border controls?!' This

dialectical karate chop has the ex‑serviceman gasping for air. Stanier steamed

on:

'I'm English but I can't go

anywhere I like. I can't go to America because I'm a Communist. Is that right?

Land of the free eh? But what you've got to remember is the difference in

material conditions between West Germany and the German Democratic Republic.

While West Germany was being pumped up with billions of dollars under the

Marshall Plan the East was paying massive war reparations to the Soviet Union.

And the West was where all the industry was don't forget. What do you think

would happen if Scotland was stuck on the end of California and the border was

wide open?' It was an argument young Frank Fleet had come up with in the pub one

night, ingenious bugger that lad. 'Bet the Scots would be building a wall of

their own if that was the case don't you think?' The ex‑corporal was blankly

bewildered. Stanier suddenly remembered Sikorski's remark: 'The fact that

you've silenced a man doesn't mean you've convinced him.' Not that anyone ever

silenced Sikorski.

The insatiable Horsefield

and Bender had relieved Ted and Fleet of half a dozen papers leaving them one

with six houses to go. At the third from the end they were invited in by a

young man with freaked‑out hair dressed in what looked like a football shirt

with green and black bars and white collar and cuffs. While they sat down on the

couch, one of those cheap spiky contraptions with polished wooden arms, his wife

made them a cup of tea. She had the fine-drawn vulpine features commonly found

in people of Polish descent. Fleet watched her with scarcely concealed

admiration; the face seemed familiar somehow.

Ted was more interested in the

bookshelf, three planks of planed pine across an alcove. He wasn't close enough

to read the titles but he recognised by their size and colour Carr's History

of Soviet Russia and most of Deutscher's work in paperback. White cracks

down their spines indicated they'd been read. 'I get the Star already' said the

lad, 'On Saturdays. But I really wanted to get in touch with the local Party.

I've been dithering for years about joining. Been involved with the Ultra Left

but it all seems so bloody pointless. They spend more time attacking the

Communist Party than they do capitalism. And of course apart from that they

don't actually do anything.' Ted smiled understandingly.

'Inertia does help preserve a

certain moral purity. And intellectual debates on Trotsky and Bukharin are not

without fascination but, as someone once said, the idea isn't to understand the

world, it's to change it.'

'Quite. But there are certain

aspects of the Party I'm a bit unsure about; like Democratic Centralism. It's

not democratic at all it seems to me.'

'What is? When did you last

have the chance to influence the choice of your local Labour candidate?' Was Ted

trying to find out if he'd rebounded into the Labour Party?

Fleet was engaged in similar

investigative speculation. His wife was a cracker, he thought, too good for him.

Wonder if she’s looking for a bit on the side?

'I accept there's no such

thing as a real, workable, grass roots democracy as we stand now, and certainly

the bourgeois parliamentary variety is a complete con, but the CP, seen from the

outside... well… ' 'It's probably a lot more democratic than you think. And

history has vindicated its structure: it has survived. Where do you think Tariq

Ali and the International Marxist Group will be in fifty years' time? Strong

leadership and a united Party are the first essentials of any revolutionary

movement.'

'I was almost on the point of

joining when Jimmy Reid left over just this issue. I admired that bloke. The

things he did at UCS!'

'Jimmy was a good Comrade, but

he was just one member of a collective leadership. Even this small branch

collected damn near two hundred quid in a house to house collection. If you'd

been with us you could have been part of that. But I must say his criticisms of

the Party structure and methods weren't too clear even in his book. Personally

I think he was overworked; he needed a rest.' He thought back to those post‑war

days in Hackney when they were all working like dogs. He'd known leading

Comrades who hadn't even had a holiday in ten years, and some who'd cracked

under the strain. There was a pause.

'I like the paintings' said

Fleet.

'That's what I do' said the

lad.

'Paint ?'

'Teach art'. Ted thought he

could detect pedagogic overtones in His argumentative manner. Just what the

branch needs thought Fleet suddenly ashamed of his engineering background, a

cultured intellectual to knock some sense into the working‑class. Bloody

teacher thought Ted, as if the movement wasn't overloaded with them already.

What we really need are more engineers; a Lenin enrolment in fact. Still he

might be good at doing the odd poster for the branch education meetings.

'I used to teach too.'

'Really ! What subject?' The

lad seemed amazed that anyone so exalted could possibly be on the knocker.

'History. But to get back to

what we were talking about before, there's a good Party leaflet on Democratic

Centralism. Perhaps I could drop it in or send it round. And if you do want to

get in touch I'll give you the branch secretary's name and address. He lives on

this estate. Call in any time; Jud's always pleased to see potential new

members.'

They exchanged names and

addresses. Ted and Fleet got up to go.

'Things in the Party are

getting better all the time. These days we're taking a much more independent

line on things, more like the Italians and the French.' Personally he thought

the big continental parties were hovering opportunistically on the edge of a

Social Democratic deviation in order to attract mass votes, but it was the kind

of line which would impress this young aspirant in fear of jeopardising his

immortal soul. 'And if there are things you don't like when you get in then try

and change them. There's really nowhere else to go. We're the only mass party

of the working‑class.'

'I'll certainly give it some

thought, and thanks again for your time.' Fleet couldn't recall having been

thanked for his time before. He felt like some great psychiatrist who'd just

pulled someone back from the edge of lunacy.

Out on the street again

they headed for the pub and Stanier's debriefing.

'Hey Ted !' enthused Fleet.

'What ?'

'It's bloody great on the

knocker ! I had no idea ! When are we out again ?'

Ted laughed.

'It's not tea and Marxism

every night Frank lad. Usually it's just: What? Who? Piss off! Slam!'

'I'll take that leaflet round

if you like. No sense in you wasting a gallon of petrol coming from the other

side of town is there?'

'Aye, all right. If Jud's in

a good mood we might get him talking about Spain.'

'Spain? Jud was in Spain?'

'Aye. International Brigade;

volunteered at nineteen; finished up as one of Franco's POWS. Then went right

through World War Two as a tank driver.'

'And here he is selling Stars

on the knocker?'

'Don't underestimate it

Frank. As Jud said last week, raising consciousness is the struggle now. He's

no intellectual but that's his strength. A lifetime in the Party; forty years

of hard work at grass roots devoted to the cause. This is where it counts.' He

waved his hand towards the sodium lit houses. 'What do you think these people

care about the Fascist Pact or the Twentieth Congress? May be the Party has been

used as an instrument of Soviet foreign policy, so what? If we'd all stayed at

home agonizing about it we'd be nowhere today; a morally pure nonentity; a

bloody debating society! Politics is a shitty business Frank, but if you opt out

of the struggle you support the status quo; there's no clean ground. So get

active and keep your conscience on a short lead; deep down it's a bourgeois

liberal. The only thing that matters long‑term is the survival of the

revolutionary party. All over the country there are cells just like ours,

waiting, ticking over, all connected to the centre. One day they'll double,

quadruple, increase ten‑fold. The structure that we've preserved intact, on

trust, will fulfil its historical task.' From a dissident of 56 it was a strange

harangue. Fleet was alive to its ambiguities. Was it over‑reaction?

Middle‑class middle-aged guilt? Or was it really the well‑tempered wisdom after

the fire?

In the saloon bar of the

Rope and Anchor they waited for Horsefield. The saloon bar, like the donkey

jackets and anoraks, was Party style. The ale was cheaper, and that might have

been a consideration with Harry and Ernie, but the others didn't drink that

much. It was just that you got a better class of people in the saloon side; the

working‑class. Or, more accurately, the working working‑class; shiftmen, OAPS,

lumpenproles. The leisure working‑class usually headed straight through the

lounge door past the NO OVERALLS PLEASE notice. The saloon bar furniture;

scuffed lino, ripped benches, dartboard, hard chairs, wobbly formica tops all

contributed to the revolutionary tone. They were symbols of virtue like

Lenin's peaked cap, Castro's combat boots and Robespierre's lodgings.

They sat behind frothy

pints of best bitter, except Bender who had been seduced to lager by his trendy

drawing office mates. An extra one waited for Horsefield. Bert Brimelow came

across; he smelled of paradichlor‑benzine.

'Now then Jud, when's the

revolution then?' He took in the group with his single eye.

'Next Wednesday Bert. Think

you can make it?'

'No, got a Union meeting.

I'll watch it on the news'

'Should be on near the end'

said Bender. 'just before the weather. Don't go for a piss or you'll miss it.'

'What have you been up to

tonight?'

'Star sales on the knocker.'

'Put that in the kitty' Bert

dropped a quid on the table.

'Thanks Bert lad. You're a

true friend of the proletariat! What you doing in here anyway? Thought Friday

was your night out?'

'Got called in. Thought I'd

have one on the way home. That stirrer motor on the Paradi blew a fuse

again.'He worked in the same factory as Stanier.

'Be seeing you anyway Jud.

Keep the red flag flying.'

'Not seen him in the branch

Jud.' said Fleet.

'No, he's not Party now. Used

to be before the ETU bust up. After that it was either give up his Party card

or his job as shop steward in the electricians. He's still Party deep down. A

good Comrade Bert.'

'Hey! Where the hell's Harry?'

Bender looked at the clock, 'His pint'll be going cold.'

'He's probably fighting the

battle of Stalingrad on somebody's front lawn.'

If Ted had made it the Imjim

river he'd have been nearer the truth. The last two houses in Hilltop looked

strangely different; bigger, more separate, but Horsefield saw nothing ominous

in that. It was dark by now. One more to sell. If he didn't flog it he'd have

that bastard Bender crowing all over the pub. A light came on and a huge shape

filled the doorway. Horsefield went into his spiel. A voice cut him off in mid

flow:

'Fucking Communist scum! Get

off my fucking property!'

Horsefield quickly spiralled up

to action stations. He still couldn't make out any features but after a

broadside like that he'd have taken on King Kong.

'Come outside and say ...' A

fist the size of a ham shank smashed into his left eye. As he staggered back

the shape came over the doorstep. Horsefield ducked the next swing more by luck

than skill, brought his knee up into the monster's balls and butted him under

the jaw. There was a muffled crack like a piece of firewood snapping under a

blanket. Horsefield could see as he bent over him, blood dribbling out of his

mouth; he'd nearly bitten off the end of his tongue: out cold. A woman was

shrieking and shouting. After Harry had lugged him inside the police appeared,

then an ambulance.

Down at the local nick,

only two or three hundred yards away, Horsefield learned that those two houses

were Police houses, and that he had assaulted Sergeant McCormack. They took a

statement and let him go. The warrior returned to the Rope. By now there were

two pints in front of his chair. He finished off the first as he filled them

in.

'Good job he didn't cop me in

the mouth.'

'It's a bloody miracle you

didn't fall down the steps on the way into the cop shop Harry' said Stanier.

'Funny that Jud, I got the

impression the lads down there didn't really like him. They treated me all

right anyway.'

'Sergeant McCormack!' said

Fleet amazed.

'Sergeant McCormack MM'

corrected Harry.

'MM?'

'Military Medal; got it in

Korea. He was a POW for eighteen months. The lads in the nick reckon that's

where he must have gone off His nut.'

'Not a good time for the

Party, that period.' said Ted, 'I remember the slogans: 'Hands off Korea!' and

'The North Koreans are shedding blood to bring Communism to Britain!' The

Gloucesters fought to the death while the Party called them capitalist

mercenaries and lackeys of imperialism. The local papers in Hackney had a

field day putting Comrades on the spot over that one. A few dropped out.'

'Aye, the emotions may have

been wrong but the line was correct' Jud stepped in, 'People were wafted about

wherever the capitalist press blew them. And because our lads were dying out

there the Party was on a loser from the start.'

'They died in Spain too Jud,

while the Daily Mail supported Franco, but nobody got upset over that.' said

Ted.

'There's the morality of the

British press for you' Stanier went on, 'But Vietnam changed all that. It

took more than the press, big business and a government hocked up to the

eyeballs to the Yanks to whitewash that war. For once the truth prevailed; and

the British Party helped it to, in the streets, in the factories.' There was a

long pause.

As Bender came back with

the third round he had a sudden thought.

'Hey Harry! You realise your

dereliction of duty will have to be considered at the next Branch Committee.

You left an unsold Morning Star on McCormack's front path.'

Horsefield grinned lopsidedly

against the spreading bruise.

'Oh no I've not George. You

spoke a bit too soon there Comrade.' He pulled out from his pocket the last

Star. It was blackened with soil and gravel. Ted leaned over and took it from

him. 'Still perfectly readable' he said, spreading it on the table between the

glasses. 'Let's see now, this month's fighting fund stands at £4560.'

Ken Clay

THE WORKER’S ROAD TO HELL

I am the best

Said the white worker

To the woman at his side

Stand down about twelve inches

So the world can see my pride.

I'm second best

Said the white woman

To the black man

By her side

Stand down about twelve inches

For women too have pride.

I'm third best

Said the black man

To the woman at his side

Stand down about twelve inches

At least I have some pride.

And I'm fourth best

Said the black woman

To the brown man

By her side

Stand down about twelve inches

For I too must have pride.

And so it went

In a steady grade

Ever downwards

Shade by shade

Until there was a human stair

For those with eyes to see it there.

And up that stair

And up and up

With elegance and grace

Stepped a multi-coloured capitalist

A smile upon his face

And up and up and up he stepped

With heavy, heavy tread

Until he reached the very top,

And stood

On the white worker's head

Bert Ward

A WOMAN’S

WORK

It was

Monday. I was sitting on the kitchen sideboard, in the lotus position, crying. I

reckoned I had lots to cry about. It was two c'clock in the afternoon and the

monstrous pile of washing on the kitchen floor hadn't even been started. The sun