|

ISSUE 13

cover size 210 x 148 mm (A5)

Voices Appeal

Editorial Committee

You Pat Arrowsmith

The Tyneside Poets Alan C Brown

Maud Watson, Florist Keith Armstrong

The Occupation Ken Fuller

An Explanation and an Apology Alan Bridie Watts

Bleached Grass Pat Sentinelia

Savages John Salway

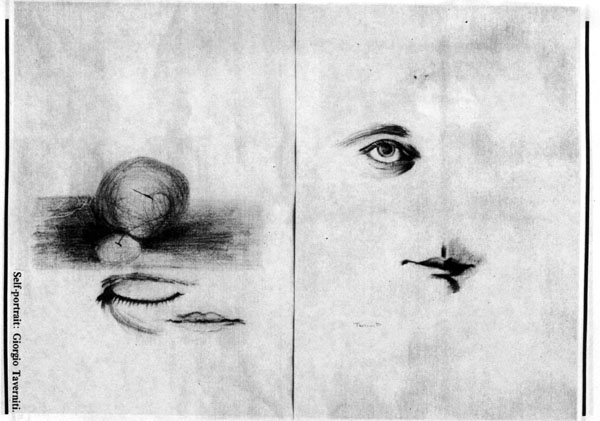

From Haifa to Die in Lebanon Giorgio Taverniti

The Stripper Jean Sutton

After You Bill Eburn

Rush Hour Bill Eburn

Absent Friends Bill Eburn

Manganese Nodules And You Les Barker

Comment on a Scorner of Mechanisation Frances Moore

A Silent Man Disguised as a Comrade Wendy Whitfield

Philpot in the City Paul St Vincent

Lambchops in Training Paul St Vincent

Natural Rhythm Rose Friedman

Power Trio Vincent P Richardson

The Hunt for the Bismarck Bert Ward

In Praise of Learning (trans by Rick Gwilt) Bert Brecht

Iry Rick Gwilt

VOICES

APPEAL

Total

acknowledged in "Voices 6", £164.23. Since then, the following donations have

been received for which we express thanks. Mr and Mrs Tartakower £4, Bob Dixon

£2, Peggy Kessel £3, GiorgioTaverniti £10, Kathy and Paul Levine £8.40, M M

Wiles £2, Mr G Doyle £1.40, May Ainley £5, Gillian Cronje £3, Horace Green

£1.40, Anon £5, a total of £45.20, which brings the grand total to date 31

January, 1977, to £209.43.

We would like

to wind this fund up by April 1, so please make your donations early.

VOICES

Editorial Committee

Some changes

have taken place recently. Alan Arnison has had to withdraw (temporarily, we

hope) because of illness. Rick Gwilt has come on as Joint Editor with Ben Ainley.

Greg Wilkinson has joined the Board to develop the idea of Writers Workshops.

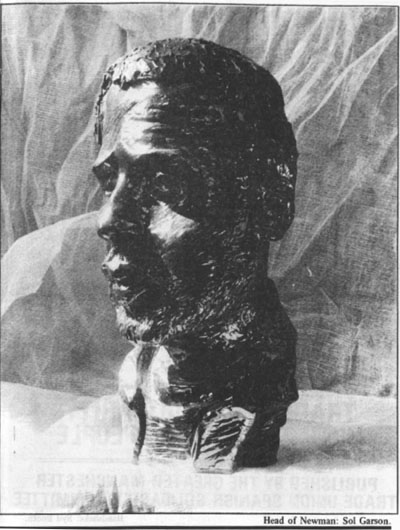

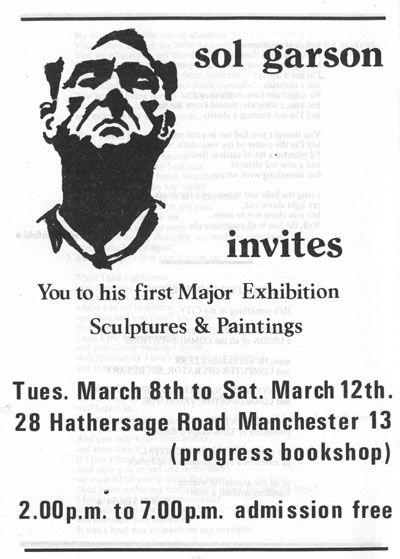

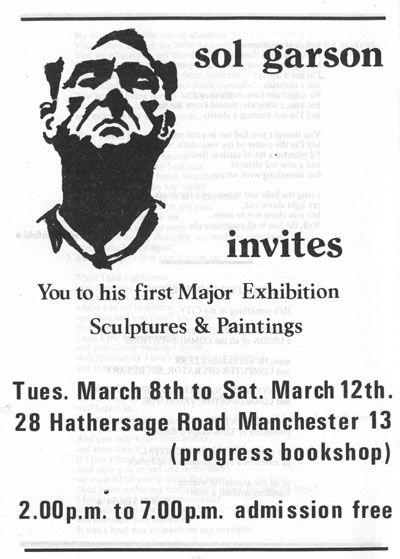

Maurice Levine is responsible for approaches to bookshops. Sot Garson becomes

Art Editor. Frank Parker remains Treasurer. Rose Friedman and Val Ohren remain

on the Committee, as does John Cooper Clarke. We have had regretfully to accept

the position that Les Barker does not feel able to function on the Committee.

Our thanks

are due for financial help from the North-West Arts Association.

YOU

You are glass.

Clear, bright, sharp-edged,

you shine, cut, pierce to the core.

Sometimes a prism,

you refract the light around you.

Ice-like you can even melt.

Or crack.

Occasionally you are shattered.

I know,

because your splinters are still in me.

Pat Arrowsmith.

THE

TYNESIDE POETS

Tyneside

Poets is a group of men and women residing in the North-Fast, who believe that

poetry should not be an ivory tower activity, but should go out to the people.

Since January 1973 we have given readings at various festivals, in pubs,

car-parks, town centres and at folk groups. Members have been invited to Sweden,

Germany and Iceland.

Tyneside

Poets hold regular meetings, give readings, issue small press publications and

stage occasional exhibitions on specific themes. We have appeared on radio and

TV, and have presented readings at the Newcastle Festival.

We have had

visiting poets from the USSR and Germany. We have set up exhibitions of Soviet

poetry, and German poetry. Poets have come, at our invitation, to Newcastle such

as: Maia Borisova, Michael Dudin, Violetta Palchinskyte and Joseph Nineshvilli

from USSR; and Oswald Andrea and others from Germany.

Our small

publications have included translations from many languages done by our members.

In POETRY NORTH-EAST we seek to bring the work of our members to the notice of a

wider public. We have had our poems translated into German and Russian and

published abroad. We have had articles about our group in magazines in the

Soviet Union, Sweden, and Germany.

Tyneside

poets aim to encourage poets and writers; they also strive to develop better

understanding between peoples.

Alan C Brown

10 November 1976

MAUD WATSON, FLORIST

bred in a market arch

a struggle

in a city's armpit

that flower

in your time-rough hands

a beautiful girl in a slum alley

all that kindness in your face

and you're right

the times are not what they were

this England's not what it was

flowers shrink in that crumbling vase

dusk creeps in on a cart

and Maud the sun is choking

Maud this island's sinking

and all that swollen sea is

the silent majority

waving

Keith Armstrong.

THE

OCCUPATION

Eric sat at

the kitchen table, chin in palm, and gazed vacantly across into the yard of the

house which backed onto his. On the garden wall of the other house, someone had

daubed a legend:

UNITED RULES-OK

He thought of

the team about which he had at times cared so passionately and for which, last

Saturday, he had fought. Now, on Monday morning, as the fact of his redundancy

began to sink in, United seemed irrelevant. Besides, he hadn't really been

fighting for them on Saturday. No, I was fighting for ... ah, I'm fucked if I

know why I was fighting. I was in a mood, had been since they told us, a week

before the event, that they were closing the factory. Then, at the match, I

remember looking around the grounds at all the people who had jobs, looking up

at where the directors sat puffing their cigars, dressed in their thick

overcoats, and suddenly I got mad and felt ashamed all at once, like it was my

fault that I had no job to go to.

When the game

started, though, the shame disappeared as we cheered the side on. There were

about twenty of us together, almost all from the same street, and it seemed like

we could beat the world, the way we felt. I even forgot about me job-until the

ball landed in the back of United's net, that is, and then I don't really know

what happened. The fighting started down the front. The shame came back. The

side was losing. A middle-aged feller next to me pushed me and called me a

hooligan because I was with the crowd that was fighting, so I kicked his shins

and belted him one. It was like he was saying it was my fault, when I hadn't

done a thing. Then the fight spread and me mates told me afterwards that I had

been doing most of it. They said it like they was proud of me, like it made them

feel good to be my mate, but it was nothing to be proud of, not really. No, I

wasn't fighting for United and I wasn't even really fighting against the people

who got in the way of my fist either, because I remember now that every now and

again I kept looking up at where the directors were, thinking you cunts, you're

no better than the sum who closed down our factory and put us on the street.

Yeah, before

the match, it had seemed like we could've beat the world, but then, when the

fight was on, the law came and we were finished. Somehow, I managed to squeeze

through the crowd and escape. That was the first time I'd been involved in

anything like that and I hope it'll be the last. But that bloke shouldn't have

called me a hooligan.

He pushed

aside his cereal-bowl and scratched his uncombed head, wondering what to do with

himself for the day. Then he heard someone at the side gate and realised that

the front door-bell had been ringing. Big Dave's head appeared at the kitchen

window.

Big Dave

wasn't so much big as fat. He was eighteen, a year older than Eric, and he tried

to appear worldly and adult, but Eric had long ago discovered that this was just

a means of hiding his lack of self-confidence. He liked him anyway. When he

opened the back door, Dave was standing there, squinting at him as he drew the

last lungful of smoke from his roll-up, which he held pinched between thumb and

forefinger.

"Where the

fuck you been, then? I been ringing the bell for ten minutes now."

"Sorry mate,

I was miles away. Come on in."

"You goin'

down to the meeting outside the factory ?"

"Christ, I forgot all about that !" Dave

shrugged.

"Can't see it doin' much good, anyway. Here, roll yourself a fag."

Eric rolled a

cigarette and lit it, the first lungful of smoke making his stomach turn as a

result of his cold breakfast.

"Where's the

old lady, then ?"

"She's on

mornings this week."

Dave had

rolled a cigarette which looked like a piece of stiff white bootlace. He held it

up to look at it and grimaced. "They'll be layin' off people there soon, as

well. Stands to reason, dunnit ? We supply Preston's with parts and if we're

closed down they can't get parts-'less they get 'em from the factory up North,

and that'll mean more expense, so they'll probably get rid of a few anyway."

"I hope

you're wrong, Dave. Christ knows what we'd do with just me old man working. He

pisses most of his wages up against the wall as it is." He bit his lip. "What's

wrong with this fucking country all of a sudden ?"

Dave started

a bonfire at the end of his cigarette. When the blaze had died down, he drew in

a mouthful of smoke and expelled it through his nose.

"I'm surprised at you,

Eric," he said, narrowing his eyes prior to taking another puff. "After all, you

don't have to look too far, do you ?" His stubby forefinger tapped four times on

the table. "Too-many-black-bastards. I thought you had that all weighed up, the

way you were taking the piss out of old Clement Atlee Armstrong the other day."

"Only because

everyone else was, and then it was only over his name, nothing else."

Dave rolled

his eyes. "Jesus Christ ! Whaddayou wanna stick up for him for-he's as thick as

shit !"

"Well, my old

son, he can't be all that thick, can he, 'cause he's got three A levels-three !"

"He'd still

be takin' a white man's job even if he had seventy-three fucking A levels."

"Well, I

wouldn't be too sure about that if I was you. I heard Donnelly talking about

this business of blacks taking jobs from whites and it just don't work out that

way." Dave pursed

his lips and folded his hands on the table.

"Okay, what way does it work out,

then ?"

"I can't

remember, but you can ask Donnelly yourself at the meeting if you really wanna

know."

"I wouldn't

ask that cunt the time of day, the murdering Irish bastard." Eric threw up his

eyebrows and pushed his chair back. "Well, I'm off to the meeting. Coming ?"

"Suppose

there's trouble ? I passed a lot of law cars on the way here."

"Oh, I don't

reckon they're anything to do with us, Dave-they must be on their way to arrest

Donnelly for murder."

"Piss off."

The high

street seemed somehow different this Monday morning, the shops drabber, the

housewives and pensioners who were now, at nine-thirty, coming out of their

husbandless, childless houses more ill-tempered, their faces pinched with a

hundred small concerns and worries and probably by one or two big ones as well.

The rubbish from Saturday's market still lingered, stuck to the street and the

pavement by intermittent October rain. An old man was washing down the steps of

the Ode on as Eric and Dave arrived at the bus stop; Eric glanced at the stills

of Kirk Douglas dressed as Spartacus.

"Not a bad

film, that," said Dave. "Went to see it last night. You seen it ?"

"Only on

telly." As they stood

in the bus-queue, Dave looked at Eric from the corner of his eye.

"Of course,

this meeting's gonna be a waste of time. You fancy nippin' down the employment

to see if anything's goin' ?" Eric grunted.

"That would be a waste of time."

The

industrial estate was five minutes' walk from the bus stop at the other end.

There was a funny feeling in the air. Looking up at the razor-blade factory and

the bakery as they passed, they could see men standing at the windows, looking

out.

"Whaddayou

think's up with them ?" Eric pressed

his lips together.

"Dunno. They're looking down towards our factory."

Dave snorted.

"It's not 'our' factory any more."

"It never

fucking well was."

Dave looked

at Eric, made to say something, then reconsidered and remained silent.

They were

late. By the time they reached the factory gate, the two hundred men and women

were listening to Donnelly as he wound up his speech. The Irishman was not big

but, as he stood at the head of the meeting, his finger jabbing the air and his

head thrown back so that his voice carried as far as possible, he looked as big

as he needed to look. With a glance at the six or seven policemen who stood on

one side, Eric and Dave joined on at the back and strained forward to hear what

was being said.

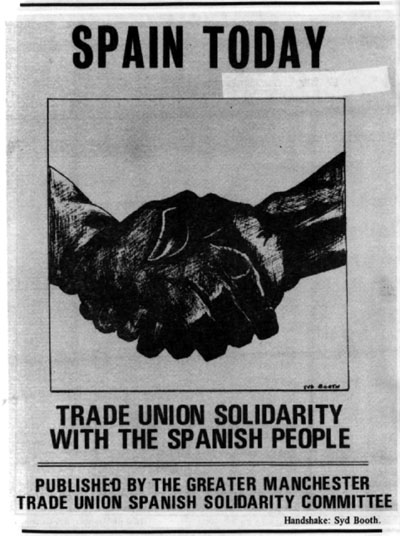

"So that's

their plan, brothers and sisters: first they put us on the street and then, in a

week or two, Preston's will close through lack of parts, or at least that's what

the workers at Preston's will be told. But the fact is that both operations will

be carried on in Spain-they are being carried on in Spain as we stand here. In

Spain, brothers and sisters, where the fact that the prisons are full of trade

unionists will mean bigger profits than ever before, even bigger dividends for

the shareholders than they got last year." Donnelly paused, placed his hands on

his hips and looked around at the meeting. "So should we accept the fact that

the business which we've built up over the past twenty years has been

transferred to fascist Spain ?"

He listened

to the chorus of noes and raised his eyebrows in mock surprise. Despite the

seriousness of the situation, everyone could see that he was about to playfully

chide them for past errors. "Ohhh, so now we all see what a tirrible thing

fascism is, do we ? From the measly little collection we took for the boys in

Spain a couple of Fridays ago, I wasn't thinking for a minute that we were all

such dedicated anti-fascists. But now it's hit us in the belly, eh ?" He smiled.

"Well, we're learning the hard way, but even that's better than not learning at

all. And I'll tell you another thing: don't be too surprised if when this has

all died down I get arrested and deported under the Anti-Terrorism Act-not for

being a terrorist, but for being a bloody good trade unionist. When you stand by

and let a law like that get passed, you don't always stop to think that it might

be used against yourself one day, but that's the kind of society we're living

in, brothers and sisters."

Some among

the audience thought that he had wandered too far.

"Yeah, but what are we gonna

do now ?" cried one worker.

Donnelly

stretched up on his toes and looked beyond the crowd to where a blue Mercedes

had drawn up, a police-sergeant bent to one of the rear windows.

"Well, first of

all we're going to let the governor in. We mustn't stop him from working just

because he stopped us, now, must we ? Move aside and let the silver-haired old

gentleman through. Of course I'm serious, brother-move aside and let the bastard

through now."

In some

confusion, the meeting obeyed and divided itself into two. The Mercedes crawled

through and stopped at the gate, where the chauffeur alighted with a bunch of

keys. While he was unlocking the gate, Donnelly swept off his hat, clasped it to

his heart and approached the rear window of the car.

"They're not at all bad

lads, sorr," he said, laying the brogue on thick and heavy, "It's only natural

that they should want to let off a bit of steam. Now pardon me presumption, sorr,

but if your good lady has any scraps that she can spare ... well, it's the

little ones, you see, sorr - they'll not be having much to eat since you're no

longer able to give us work and look after us."

The managing

director opened his mouth, licked his lips, frowned and told the returned

chauffeur to drive through the gate.Donnelly

straightened up and called out:

"And now, brothers and sisters, we're going to

occupy the factory. Come on."

The men

reached the office area before the Mercedes and so the managing director found

the way barred. He waited around for ten minutes and then drove away once more,

stopping outside the gate to converse with the sergeant. Donnelly, meanwhile,

had sent a man over the back wall to the house of the night-watchman. The man

returned forty-five minutes later with a full set of keys and by 11.15 the

factory was occupied in the fullest sense.

A meeting of

the shop stewards was called and this lasted until noon. The occupation, far

from having been as spontaneous as it had appeared, had been planned over the

weekend by the shop stewards and a handful of the most trusted workers. Now they

ironed out the finer points, drawing up watch-rotas, arranging for bedding and

food to be shipped in and for those workers who had not turned up for the

meeting to be informed. Someone was sent across to Preston's to advise the shop

stewards there of the occupation and of the future which lay in store for them. As Donnelly

left the meeting, one of the senior shop stewards walked with him across the

yard.

"I don't think you did us much good, Bob, talking that way to Jamieson." Donnelly

snorted contemptuously.

"Get away with you ! He's so thick he couldn't make out

whether I was taking the piss or not. Hey, young Eric!"

He left the

shop steward and walked over to where Eric and Dave were standing. Eric looked

up and, as if sensing that what Donnelly wanted to say to him was confidential,

patted Dave's arm and moved away. Donnelly

placed a hand on Eric's shoulder.

"My spies tell me that you were in some

trouble at the ground on Saturday."

Eric dropped

his eyes, not knowing how to meet the man's gaze.

"Well, at

least you're ashamed of it-that's a good sign. But why did you have to get mixed

up in a thing like that?"

Eric

swallowed. "It's hard to put into words. It didn't have much to do with the

match, really. All kinds of feelings were mixed up in me. One minute I was glad,

happy to be with me mates, then I was ashamed, 'cause all I was was a yob who'd

just lost his job and didn't know any better." The Irishman

smiled down at him.

"You know better, son-you know it and I know it and that's

all that counts. Never mind what anyone else thinks, least of all bastards like

Jamieson."

They walked

across the yard together. Donnelly put his hands in his pockets, took in a large

sniff of air and looked about him, as if visualising how things might be if,

instead of a defensive action, this occupation were of a more permanent nature.

"You see,

Eric," he said, "you'll find that every class system on earth, once it's

outlived its usefulness and is dying, will give rise to violence and to what

they call a 'breakdown in law and order.' That's because the system can't

satisfy the simple demands of the people any more and because something tells

them that the law is only a means of keeping them down anyway. But that doesn't

mean that this violence is a good thing, because nine times out of ten it's just

workers fighting workers. Then again, sometimes the violence is within the law,

like it was in Rome, where they made slave fight slave. They're happy-the

slave-owners, the barons or the capitalists-as long as worker fights worker, and

that's what you were doing on Saturday. What people like us have got to do is

turn workers' thoughts on creating a system where everyone can have a job, a

house, enough to eat and enough to do with his spare-time, building up his mind

as well as his body." He paused and grinned. "But you're not ready for that

yet."

Eric felt

better, no longer ashamed, because Donnelly understood. That was the trouble:

not enough people understood.

"What d'you

think's going to happen here ?" The Irishman

scratched his head.

"Oh, the police will come along and try to get us out. If

for some reason they don't succeed, then we'll try and get the government to

support us. But even if we get that far, it won't be far enough."

"How d'you

mean?" Donnelly

stopped, turned to Eric and smiled.

"You go away and see if you can answer that

one for yourself, then, when all this is settled one way or the other, we'll

talk it over"

Eric had been

given a tiny piece of understanding and was beginning to realise that an

experience was not half as frightening if it was understood. As he returned to

Dave, he noticed Clem walking away. Dave shrugged

sheepishly when he saw the look on Eric's face.

"Yeah, well, he ain't all that

bad," he said. "You were right about them A levels, anyway. He was just telling

me what the law might try to do to us - conspiracy to trespass and things like

that." Eric

remembered what Donnelly had said about Rome.

"Talking about Clem, did you say

that you saw Spartacus last night ? Well, don't you remember that bit where Kirk

Douglas was forced to fight that black slave, and the black slave, instead of

killing Kirk Douglas when he had the chance, attacked the poofs who were making

them fight ?"

"Yeah, that

was good, that bit. " Eric had been hoping for more. "Well, don't you see: he was

a slave, the same way Kirk Douglas was; Clem is a worker, the same way we are.

Why should we fight Clem when what we should be doing is taking on the bosses,

us and Clem together !" Dave frowned

and nodded slowly.

"That makes sense, I suppose, but how we gonna do that ?" Eric thought

desperately for a few seconds and then shrugged.

"I don't know, but I reckon the

time's come to find out."

In the early

afternoon, word came that the police were ten minutes from the factory. Eric's

stomach tightened for a moment, but then he drew on his new understanding and

the fear passed. The thought uppermost in his mind was then what a pity it would

be if the police succeeded in turfing them out, because in a few days people

would have forgotten that the occupation had ever taken place. He went to the

stores for a pot of paint and, when he returned, began to write on the wall:

THIS FACTORY OCCUPIED BY THE WORKERS and then the date. A group gathered around

him and so when he had finished he handed over the pot and brush to someone

else.

The police

were just entering the industrial estate. The workers, the men and the women,

became tense. Hands fluttered nervously. Nails were bitten. Donnelly went into

conference with the shop stewards and even his confidence seemed to be running

out. Then the men on the gate began to shout, jump up and down and wave their

arms wildly. So this was it. The end of the occupation was in sight.

Or was it ?

There came a roaring sound, low at first but growing all the time. Men broke off

their worried conversations and moved nearer the gate to see what was happening.

Donnelly looked at his shop stewards and grinned victoriously. He knew what was

happening. When the head of the column appeared, the workers at the gate began

to cheer. The entire workforce of Preston's-750 workers-was marching to the

factory to seal off the entrance from the police.

Eric threw up

his arms and laughed. His laughter became infectious and Dave, Clem and others

joined in. Eric caught sight of his mother among the marchers, which meant that

she must have stopped on after her finishing-time. Relations at home were a bit

strained at the best of times, but now he felt closer to his mother than he had

ever felt before, and proud, filled up with pride.

As they ran

to the gate, Eric noticed a sign which someone had painted:

THE WORKERS' RULE-OK

He smiled but

knew inside that it was not strictly true. In the crowd at the gate, the feeling

that washed over him was similar to the one he had experienced at the start of

the match on Saturday, although the feeling now was far finer, stronger and more

elevating than anything he had known before. Yes, together we can beat anyone

and one day we will.

One day ...

It was the biggest thing that had ever happened to him and yet even now he was

asking himself just how big it really was. We're strong enough to beat the law

today, but what about tomorrow ? What about all the other coppers and all the

soldiers and all the judges and all the other bosses ?

He remembered

the question he had asked Donnelly and the answer was there, at the back of his

mind. Yes, when all this was over, he'd have a long talk with Donnelly.

Ken Fuller

AN EXPLANATION AND AN APOLOGY

In Voices 6

we printed a poem called "Alan". On the contents page it was attributed to Sam

Watts. Under the poem itself, we had simply written "Watts". The poem was

printed without an explanation of the circumstances under which it was written.

The writer was Bridie Watts, the mother of Alan Watts, who was an active leading

member of the Young Communist League in Liverpool, and an EC member. Alan was

stabbed to death by a man who was drunk at the time. The family Sam (the father)

Paul (the brother) Bridie (the mother) were shaken to the core by the tragic

event. Bridie's verses are more a cry of anguish than a poem, but we believe it

deserves to be printed. Here it is then with this explanation and with my

apology for the way it was treated in the last issue.

Ben Ainley.

ALAN

No moon-no sun-no stars

No morning-no evening-no light

No trees-no flowers-no spring

No birds-no song-no rainbow

No seas-no sky-no streams

No smiles-no joy-no laughter

No music-no warmth-no love

No tenderness-no beauty-no feeling

No tomorrow-No Alan

Bridie Watts

BLEACHED

GRASS

The colour in

my mind is of bleached grass. "Some say the world will end in fire..." -gun-fire

from Soweto to Derry this summer of '76.

Meanwhile, I

am lulled in an August seclusion of rural peace, solaced by the image of a small

child in pink frock and curls; a child taking her first shaky steps, holding

only my breath, as she treads, tentative, on dry ground. This is the long, hot,

summer of eternal childhood-the sunlit smile in sunlit fields-the snapshot which

my mother has treasured for decades being identical to the one in my mind's eye

today. We are accustomed to this continual regeneration-as accustomed as we are

to water springing from the earth.

Still the

gun-fire cracks across my brain, stridencies which also hold my breath, and the

colour in my mind is of bleached grass. Perhaps it is my eyes that are too dry.

Pat Sentinella.

SAVAGES

(For the dispossessed people of Diego Garcia)

Those who

While the waters of the forest

Drop

Pare and trim and mill

A branch of mahogany

To a point

Or those who

With a casual cross

On a memorandum

Sweep away

Acres of men and women

Who sees the wood?

Who sees the trees?

John Salway

FROM HAIFA TO DIE IN LEBANON

Published in Arab Palestine "Resistance" No. 2

February 1976 by Palestine Liberation Army.

Images covered with dust; people!

My father pushing me in a cart

From Haifa ... to Die in Lebanon.

I was holding an open pomegranate

And a young sparrow!

I remember the sparrow

Picking at the ruby seeds

Sharing my bread-crusts

In Lebanon

Tossed about

Later: A target between two guns

I woke and stole a last look at the sun

Still here in my dead pupils

Take it ! !

I woke and died

Holding my child,

Dreaming:

I saw again fathers pushing carts

Then the burning red Flowers,

And a grey wave chasing me

Zionism closed my eyes

But you ... open them

But you:

Tear the hearts from the lifeless bodies

Take them back

Giorgio Taverniti

THE STRIPPER

They were the

last to leave. Lingering slowly up the slope to the car-park. Mellowed by the

night's drinking, reluctant to leave behind, the brightness and laughter.They

were still laughing and joking, tossing comments across to one another, sharing

a bond in the enjoyment of another evening together. They were content, like

fully happy cats, who looked no further than the next saucer of milk.

Only Claire

was quiet ... she gazed up at the sky, and the dark troubled clouds, that

promised rain. Her attention was divided between her friends, and her own

thoughts, and she made little contribution to the conversation. One couple

shouted goodnight, and with arms entwined, walked away to their car.

There was

ribald commentary on their early departure from the group. One of the men,

clenched his fist, patted his upper arm with his left hand, and made a punching

movement in the air.

"Wheigho! had

a promise Jack ?"

Everybody

laughed, including the couple in question.

"It's nowt to

do with you John", shouted Jack good humouredly.

They climbed

into the car. Jack sounded the horn, waved, and drove off down the slope,

followed by shouts, and cat-calls. They gazed

after the disappearing car.

"She's

certainly a character, isn't she ?"

"Aye.

Marvellous for her age, and good fun."

"Good bloke

Jack, too, he's sound, dead sound."

The men stood

there, smiles on their faces, hands in pockets. Everything was good on a

Saturday night. They looked forward to it all week. On Saturday nights, Monday

morning was buried.

"What about

that stripper last week Dave ? She was a real artist, that one." Claire came

down to earth. She was part

of the group again, listening intently, and Dave was careful to avoid her eye.

"Did Dave

tell you, Claire ?" He didn't wait for an answer, but carried straight on. "A

real genuine artist, and just listen.." He nudged

Claire, unnecessarily, for her attention.

can you

just see it, this stripper pranced up to Pete, pushed her bust right at him, and

bear in mind she was topless, and then she said-'Take me knickers off."'

He roared

with laughter, his eyes dancing at the picture conjured in his mind. Claire

laughed too. Dave chuckled, and shook his head from side to side. He was

incensed with merriment at the reminder of Pete, and the stripper. He felt it

safe to laugh, because Claire had laughed too. Still

smiling, he caught her eye, she stared straight through him.

"That was the

benefit concert, wasn't it ?"

She directed

her question at John, every time she looked at Dave, she opened her eyes wide

and stared coolly at him, before flicking her glance back to John.

"Yeah, it was

a great night, we didn't know there was a stripper on though." John's girl

friend Liz had joined the group in time to hear the last words.

"I'll bet you

didn't" she said. Claire was

careful not to let them guess that she was not in tune with their own jolly

mood. Only by her eyes, did she convey the message to Dave. She felt

anger, not so much at their night out, but at their obvious enjoyment over it,

with their small boy enthusiasm, and great shouts of laughter, as they

remembered more details to relate.

"Do you know

what riles me though ? If us women went to see a male stripper you wouldn't like

it would you"

"Ah well,

that's different, isn't it. I mean, it seems more crude somehow." This reasoning

came from another of the male majority of the group.

"Why is it ?" Liz joined

Claire, in her questioning.

"Well it just

does that's all. Men have always gone to see a stripper."

"There, you

see" said Claire. "Women's Lib kicks up about things like that not that I

want to see a male stripper, but if I did I shouldn't be made to feel odd about

it."

"Mmmm, true,

true but it's still different." John laughed,

and patted Claire's shoulder.

"I'll agree

there", said Dave. "It's like you always say Claire, one rule for men, another

for women - it applies there." He slung his arm around her. She stretched her lips

in a fair imitation of a smile. His male ego,

thought her silence signified defeat.

"Come on all you happy people" said Liz.

"It looks like rain". John held his palm up.

"Here it comes."

The rain fell

in large scattered drops, and before they reached the cars, a relentless sheet

of rain, stung their lightly clad bodies. Their calls of good night to one

another were brief and hurried. In the car Claire was careful not to mention the

strip show and Dave made no mention of it either, no explanation of why he

hadn't told her about it.

I'm not

bothered about it, she told herself, but he might have mentioned it. Why didn't

he ? If he'd told me about the stripper, I wouldn't have minded. A dark horse if

ever there was one, and he had the nerve to say she was as deep as the ocean ...

It was his stock phrase when he found her out in a white lie, or an omission of

confidence.

There was no

knowing men, that was for sure, and they talked about women. It was an effort to

keep silent about it, a test of will power, but she managed and was quite

pleased with herself. Yet she knew that at some future date she would have her

say. She could sense his relief, and was slightly amused.

It had been a

hot tiring day, and Claire thought longingly of the hot bath she had promised

herself. She made the beds quickly, not bothering much about shaking the pillows

up. She was tired

after her long day, serving in the shop, and wanted nothing more than to laze in

the bath, reading and smoking. Just then

Dave entered their bedroom. He made a grab for her as she passed him, and she

dropped her cigarettes.

"Ouch" she

gasped, and pulled herself away from his fierce embrace.

"You were different

downstairs, What's up, don't you feel like it ?"

"Yes, but I was just going for

a bath."

"Never mind

the bloody bath." Movements and

voices reminded them they were not alone in the house.

"The traffic around here

is too congested" said Claire.

"Well come on

then. Let's go into the bathroom." From the

lower regions of the house, someone shouted for Dave. He cursed.

"I'll be up in

a minute" he said to Claire.

"OK", she

picked her cigarettes up off the floor, grabbed her magazine, and went into the

bathroom, leaving the door unlocked.

She stripped

down to her briefs, and stretched her aching body. Mmm, that felt good, She

turned the bathtaps on, and threw in some bubble-bath, swishing the water, till

it looked like pink candy-floss. She caught sight of herself in the mirror. The

steam wouldn't do her hair any good, and they were going out later. She put some

rollers in quickly, and wound a pink, chiffon scarf, mammy-fashion round her

head. She reached for a bottle off the shelf. It was after-shave lotion.

Footsteps pounded up the stairs. Ah well after-shave was as good as perfume. She

splashed it liberally over her neck, and down her arms, and replaced it quickly

back onto the shelf, seconds before Dave entered the bathroom. He stood looking

at her. His eyes glistened. He locked the door without taking his eyes off her.

The sound he made, could never be found in a dictionary. It was an ejaculation

of appreciation, and expectation and sounded like 'Ffwar'

"Do I put you

off?" asked Claire, referring to the rollers in her hair.

"God ! No.

Come here quick."

She swayed

towards him, pressed her breasts agalnst his chest, and twined her arms around

his neck. She gazed

deeply into his eyes, then lowered her lashes. She stifled a laugh.

"Take me

knickers off then" she breathed huskily.

He pushed her

roughly away from him. The movement

was so unexpected, she almost lost balance.

"You've put

me off now" he said, and slammed the door as he left the bathroom. "And leave my

bloody aftershave alone" he shouted from the other side of the door. She gazed

at the door through which he had made his hasty exist.

Well ! There

was no knowing men.

She was still

smiling to herself, as she settled herself in the bath, lit a cigarette and

reached for her magazine.

Jean Sutton.

AFTER YOU

"What will happen to us?

she said. "That's what worries me

"We shall die" said I.

"Doesn't it bother you" she said

"not to know who will be the first to go ?"

"I had rather hoped" said I

diplomatically

''it would be me

"That's what I mean" said she

"You men. Self first,

self second and self again.

Bill Eburn

RUSH HOUR

"Why do you feign sleep

as soon as I appear

looking for a seat

that isn't there ?"

"Madam-

(I kiss your hand)

I simply cannot bear

to see a lady stand."

Bill Eburn

ABSENT FRIENDS

''So many gone' said my Dad

"I'm afraid to look in the glass."

"For fear of what you'll see there ?"

"No son. For fear I shan't be there."

Bill Eburn.

MANGANESE NODULES AND YOU

Take me back to the land of the manganese nodules,

To Chorlton-cum-Lately in your soft cobalt twilight;

Half-past-my-lovely, irridescence-of-rainbows,

Shine on this whiteness of my phosphorus midnight;

My life needs your colours:

Take me back to the land of the manganese nodules

And share with me all of your magical wealth.

Cowrie Shells, Jingly-bells, seahorses minglingamonga

Cornucopia of giving to you: my life's treat:

If I were the Phosphate Commissioner of Tonga

I'd lay Queen Salote's Phosphate before your small feet:

My life needs your taking:

Take me back to the land of the manganese nodules

And share with me all of your magical wealth.

In Chorlton-cum-Sideways every Saturday evening

The rest of the world makes libations down dark entries:

But I stays where I is and give gifts of my thoughtness

That try to slip by your self's forbidding-cold sentries;

My life needs your listening:

Take me back to the land of the manganese nodules

And share with me all of your magical wealth.

Take me down by the shoreline of Chorlton-cum-Uppance,

Interweave with the laurel that grows down Hardy Lane;

Receive all that I give, from a world to a tuppence

Interweave with all that I am, whether life or rain;

My life needs your being:

Take me back to the land of the manganese nodules

And share with me all of your magical wealth.

Please sing me your sweet song that revolves round my earole,

Does two laps of my ear lobes and twice round my mind;

Please let your lips touch me with a song and with touching

Sing your sweet manganese song, sing my life, sing, sweet kind:

My life needs your kindness:

Take me back to the land of the manganese nodules

And share with me all of your magical wealth.

Les Barker

COMMENT ON A SCORNER OF MECHANISATION

It's easy to see this scholar thinks and feels,

changes his linen, takes his decent meals,

without perception of the household wheels.

She who provides the comfort for him leans

joyously on the comfort of machines,

like us, who worked at washtubs in our teens.

Those poets who rest in neolithic themes

have less in common with man's stone age dreams

than the tractorman by whom the tilled earth teems;

than the twisting girls in the noisy dance halls,

the swaggering youths by the factory walls,

whose hands make plenty, whose future calls;

calls to take charge of the toiling machines

that they make and work as Plenty's means.

Frances Moore

A SILENT MAN DISGUISED AS A COMRADE

A silent man disguised as a comrade.

We think we have a choice on the question of marriage

but for my class

the choice is narrowed merely to a choice between one man and another

and even that is sometimes 'de rigueur'.

On the appointed hour we took our vows

never to regret but often to wonder what they meant

What had I meant?

Like all the rest we bump and grind along

each in our private cells behind a private door.

Never certain if it's only us who have problems,

never certain if the fault is ours

and had we made the wrong choice ?

Never realising we had no choice anyway.

Four years cloud the memory and was it always like this?

Did we always lie side by side

just watching the trees outside the window

and feeling desolate,

lonely?

In each other's pockets all the time

and yet we lock our minds away,

apart.

Occasionally we send long distance messages

Washed up, marooned on the island of marriage.

Bewildered, battling to constrain the circumstances

by the strength of my reason

and not succeeding,

I was picked off by a cruising shark

a spider asked me into his parlour.

Crushed by some enigmatic event

an emotional spastic

collecting women in his web

watching them struggle, tangle,

give in to his effortless superiority.

His malignant speculations pay off, and one by one

we fall into his bed

with the cold weight of coins in an empty safety box.

I deluded myself.

I thought I'd found an answer and opened up our marriage.

I was warmed by the glow of new communication,

by the conception of a network of non-exclusive lovers.

Free love. My love is available;

one owner only; slightly soiled though in good working order.

However, you seemed only in it for the parts.

You only wanted some spares

to patch up your own rusty framework.

Soon, that's all you'll be.

A rusty junk-heap of everyone else's left-overs.

If I believe it surely someone else does.

Why did you only want my icing?

Did you hope you were stealing my most precious possession?

Or someone else's?

My love is not finite, nor an absolute.

You looked through my letter box and thought you'd stayed the weekend

You were barely on my threshold.

I was ready there to welcome you

You moved me, and I had faith, comrade.

Your mind and heart are not fresh, comrade.

You are not being honest with yourself.

You speculate in emotions

and call yourself a communist.

Your silence betrayed me.

I was at peace in it.

I liked your eggs and bacon,

it was nice to have my bath run,

but I'd get that at a hotel, wouldn't I ?

You were irritated by my reality

and the impermanency of sexual tension.

You were impatient with my pain

in a hurry to despatch me.

Quite relieved to strip away my confidence.

I could feel myself shrinking, my outlines reducing;

I felt a small child again.

not the woman that you'd made me.

When I had nightmares

you diagnosed a disturbed mind.

I sat all night with half a shandy

whilst you sat in silence,

and then said you didn't know me.

You didn't want to.

I said I felt unwelcome

and you kindly made me drunk.

Well fortunately I don't suffer from hangovers,

and that includes you.

However, I learnt a lot.

You said my art must be a contribution:

well here it is.

You said you only got to know people after you'd been to bed with them.

That rules out a hell of a lot of people.

And you only know their bodies,

and even then it's not your eyes and mind,

it's just a hand, a thigh.

And once you've had one in the dark

we must all be pretty much the same.

Didn't you realise my body is only where the real me lives ?

I learnt to take the initiative myself

although I might have chosen better.

But comrade, you moved me.

It was a hard way to teach me my strengths

and your weaknesses.

I have weighed them up

but my love is not a sacrifice at your altar.

I'm not a martyr

nor a christian.

We might not have much choice

but you, a comrade, should know the way,

and I'm not running a charity.

You thought you had me in your orbit,

but I'm the centre of my own circle, comrade.

I'd planned a bit of nuclear fission

and a new red element

but something went wrong.

I rang the bells and threw open the doors

my light shone out,

but you chose not to enter.

Well, the loss is all your comrade.

Wendy Whitfield.

PHILPOT IN THE CITY

He's something in the CITY

an ENTREPRENEUR-and aims to start

a UNION of all the COMMUNICATIONS

men. He will include CLERK

and COMPUTER-OPERATOR, SECRETARY

and SYSTEMS ANALYST; OFFICE MANAGER

and CO-ORDINATOR; PROMOTER

and NEGOTIATOR and of course, his own

profession of LINK-MAN collecting

the tube-tickets. For extra CAPITAL,

he enters in a book names and addresses

of all the wonderful women

travelling without a ticket.

Paul St Vincent

LAMBCHOPS GOES INTO TRAINING

Chateauneuf du Pape; German/Hungarian/Yugoslavian

Riesling; Cotes du Rhone/du Provence; Cyprus

Sherry-that's not the half of what he's giving

up for the Contest. He must also say NO to his

better-half of a dream Sociologist, NO

to self-abuse to the SUN and MIRROR sin-page.

But Crusades have never been won by compromise.

He must nail the lie once and for all-of fecklessness,

lack of application, racial special

pleading. The early-morning job through

the park, six weeks on the building-site

and regular ann-wrestling have done wonders

for the body. But the mind, Lambchops, needs

muscling up. His strongest rival is a woman

using Psychology to unnerve him. She is out,

they say, learning to piss at the roadside without

wetting her shoes. It's been tried before,

darling, it won't wash, Lambchops will learn

to play chess, to count in Yiddish, to recognise

Mozart. He will be complete for the contest:

body of Muhammad Ali, mind of a great Cynic

and Chinese all over-with the world's computers

date-matching him. Training over, he relaxes

with a Shakespearean Sonnet, and stays awake

pondering the strangeness of things. Why for instance

do they need to use knives tomorrow for the darts match?

Paul St Vincent

NATURAL RHYTHM

It was on my return journey

That I began to realise who he was

Looking at him as though

For the first time

Striding forth to conquer some world or other.

I let him pass

Then called after him

"Why so fast ?"

He turned his head

To give me a tolerant smile

Before answering.

"It is our urgency

which helps to bring

The shape towards completion

Surely you are aware of this by now ?"

"How well did you spend your day ?"

But before I could frame my answer

He had passed out of sight.

Rose Friedman.

POWER TRIO

A Statesman

once a revolutionary became a politician matures

retires

A Politician

once a revolutionary aspires

retires.

A Revolutionary

never retires.

Vincent P Richardson

THE HUNT FOR THE BISMARCK

What's the buzz?

The Hood's gone down.

The Hood's gone down?

The Hood's gone down.

What's the buzz?

The Hood's gone down

That's the buzz

The Hood's gone down.

Twelve hundred pairs of eyes and ears,

Incredulous

Let's have it clear.

The buzz is that the Hood's gone down.

The Hood's gone down?

The Hood's gone down.

The buzz is that the Hood's gone down

That's the buzz

The Hood's gone down.

What's the buzz ?

The Hood's gone down.

What sank her ?

Tin fish ? Junkers?

The buzz is that the Hood's gone down.

A.R. End of message.

The Bismarck's out,

The Bismarck's out,

That's the buzz

The Bismarck's out.

The buzz is that the Bismarck's out

And we are looking for her.

What sank the Hood?

The Bismarck did.

The Bismarck did?

The Bismarck did.

What sank the Hood?

The Bismarck did

And we are looking for her.

The fog as thick as peasoup fell,

Concealing all around us

The skipper will address the crew

And so end all the rumours.

The Hood is gone

The Bismarck's out

A fleet is searching for her

The Ramillies has joined the hunt

Revenge will take her convoy

Twelve hundred men went down with Hood,

Two thousand went with Bismarck,

Where is the sense

Or what the good

That sends men seeking others blood

Is there a thing called brotherhood ?

I wonder

Bert Ward.

IN PRAISE OF LEARNING

Bertolt Brecht

(From the play "The Mother", based on the novel by Maxim Gorki)

Learn the simplest things.

For those whose day has come

It is never too late.

Learn your ABC. It's not enough, but

Learn it. Don't let it get you down.

Make a start. You must know everything.

You must take over the leadership.

Learn, man in the asylum.

Learn, man in prison.

Learn, woman in the kitchen.

Learn, sixty-year-old.

You must take over the leadership.

Find yourself a school, you who are homeless.

Get some knowledge round you, you who are freezing.

You who are hungry, grab yourself a book: it is a weapon.

You must take over the leadership.

Don't be afraid to ask, Comrade.

Don't let them talk you round,

Take a look for yourself.

What you don't know yourself

You don't know.

Check the bill,

You must pay it.

Put your finger on every item.

Ask: how did that get there?

You must take over the leadership.

(Translated by Rick Gwilt).

IRY

(This story

is dedicated to comrades in UCATT, especially John Madden, who taught me a lot

about being funny, and Bert Smith, who taught me a lot about being serious.)

Iry moved

onto the top floor of the Bull Ring a few months after I did, just as winter-was

closing in. It was a dull, wet Saturday and I'd been out selling the paper on my

own block. It was one of those days when a lot of people hadn't bothered to get

up, but those that had were more likely to buy a Star rather than splash their

way to the shop. Later, the rain had eased off and I was out on the walkway,

looking down over the parapet. In the adventure playground the kids were

climbing railway-sleeper mountains and swinging their way across mud-puddle

rivers.

In the corner

of my eye I could see a figure approaching, hugging close to the wall. I turned

to see an old man with very black skin and very white hair. He was very tall and

walked as if he were trying to hide the fact. Under a faded grey suit, which

fitted him the way a flag fits a flagpole, he wore a blue-green shirt open on

the neck, so that the white tufts of hair could be seen sprouting up from his

chest. On his face he wore a sheepish half-smile like a permanent apology. I

never once saw him wear anything different, except for the one day when

something happened that really cracked him up.

I showed Iry

how to work the electric meter-told him it cost a lot but he'd get some of it

back at the end of the year, providing the meter hadn't been robbed in the

meantime, which was what usually happened. It reminded me of the night I broke

Julie's meter open with a hacksaw-because it hadn't been emptied and too many

people knew she was moving out. We took the whole box down to NORWEB next

morning wrapped in a headscarf. After the meter, I explained to Iry about the

central heating, and he kept nodding. I asked him if he understood and he

nodded.

I didn't see

much of Iry for a while. With a fifty-foot drop for a back yard and a latrine

for dogs at the front, people on the Crescents didn't usually see much of their

neighbours. It was getting on for Christmas when someone called and told me that

Iry had been starving and freezing himself to death in there, paying £5.80 a

week rent and still only getting £1.50 off the SS for his old room down the

Moss. Some kids had found him sitting up in bed silent and shivering when they

broke in to rob the meter. They'd gone ahead and robbed the meter anyway,

because old habits die hard, but when they'd told someone's main, saying the

door was already broken open and they'd just walked in to check up. It turned

out Iry was only forty-seven-he just looked old.

Iry had come

straight from his village in Jamaica to the boat at Kingston to the train at

Southampton to another train at London to Manchester. It was the only journey

he'd ever made in his life, and he'd been lost ever since. When he sat down to

the dinner I'd cooked up, he didn't eat fast or hungrily, just steadily got

himself outside it so I began wondering if he had hollow legs. I asked him if it

was right that the woman from Social Services was getting him sorted out with

the SS and he nodded. I told him that was better than if I tried to help-I

always ended up losing my rag with those people. He nodded again.

I didn't see

much of Iry for another few months. I saw him once shuffling down to the

'Junction', but I had a Union meeting to go to, so I didn't join him for a

drink. It was the year Grocer Heath hit us with a three-day week and Wimpey's

hit us with a transfer to Rochdale. Most of us couldn't take to rambling over

the moors at seven every morning, and one by one we jacked up. I got a start

with Hamer's in Salford, building a new telephone exchange.

It was all

right while we were on digging the foundations, but as soon as I was doing a lot

of work with a drill, cutting out columns that had been poured wrong, I started

getting a head full of concrete dust and pretty bad ear-nose-and-throat trouble.

I was surprised I'd managed to last so long-not so much on account of such

natural causes as 'the dust', but because of the arrival of a gangerman called

Ollie. We'd been labourers together when I was doing it for Taylor Woodrow's two

years before. Anyway Ollie took one long hard look at me, then came out with

that immortal line: "Haven't I seen you somewhere before ?" A day or two later,

George was moaning as usual about the job, and I was ignoring him as usual. Then

Ollie stops shovelling concrete and says to George, "There s the man to talk to.

He's real strong for the Union. He'll sort your problems out for you." Now I had

to hand it to Ollie for moving fast-he didn't want any trouble where he was

gangerman and he'd chosen just the right man to put the bubble in, right under

my nose. You could practically see the steam rising from George's ears, like

he'd got the message and was already thinking about the shortest way to the

office. George had been with the company fifteen years and was the nearest thing

to a firm's man you'd find outside of Madame Tussaud's. Archie, the joiner, was

another gold-watch candidate, and it was obvious the agent had given him the

nudge. "Hey, I hear somebody say you are a Union man ?"-"Well, you can't believe

everything you hear, Archie." So I was just concentrating on keeping my head

down for a while and not getting provoked, especially after Rod got the bullet

first week we were there for asking questions about the bonus a bit too loudly.

It was in

April it all happened. I remember that because I was in hospital on April 1.

Well, there were telephone tables installed on fire escapes, backs getting

scrubbed with yard brushes, sets of gnashers turning up in cups of tea and

enemas being administered to folks with sinus trouble. And rumours being spread

that I was trying to take my mind off the operation coming up. A couple of days

of agony after I came back thrashing and moaning and minus tonsils, then I got

around talking to the really old blokes. Two old Jewish blokes I remember

especially. Mr Caradon was the one the nurses liked -soft and appealing with

rabbit's eyes. But I reckoned Mr Locker had a bit more life in him. Ugly old

feller with short-sighted frog's eyes, too proud for most of them. Eighty-three

and dying of cancer. So I was told on the quiet, as he wasn't supposed to know.

But he knew all right, he just wasn't letting on. He'd decided he wanted to be

alive till he was dead.

When I got

back home, there was still no money from the SS and I was just about broke. So I

signed myself off the sick and phoned the firm to say I'd be in on Monday. Then

I phoned the SS, who swore blind they were going to put a giro in the post right

away. Well, Saturday went and Monday came and still no giro. So it's off to work

and see the agent, who's terribly sorry but there's no chance of a sub first day

back. He seems a bit over-confident, like he's got everything set up since I've

been away. Most of the lads seem less alive than usual, but may be that's just

the way it seems to me. I'll have to get working on them again quietly.

Dinner-time

comes and I'm off to the SS. In out of the daylight and the lunchtime rush on

Ancoats Street. Into the dingy waiting room, where nobody moves, except for kids

who fidget and scuff because they've not been taught how to behave yet. There's

at least thirty-seven people, lined up in rows with glazed expressions, like

it's the queue for Belsen. Hard chairs specially designed to break every bone in

your arse if you don't learn to go numb. I see Iry there on the front row, and

he smiles his half-smile and nods to me. I realise he fits in here, looks just

like the rest of them. And something's boiling up inside me-like I'm not in the

mood for queuing up here losing an afternoon's wages and may be my job. Only it

goes deeper than that.

People turn

to look as I go straight through the sliding door without any invitation from

the loudspeaker. Then there's me and this clerk having this conversation not

quite with each other; I've been waiting three weeks and I'm sick and tired of

waiting; he's sorry to the young lady that this young man is behaving so

unreasonably and preventing him from attending to her case; I'm saying don't

fall for that love they're just trying to get us at each other's throats, and

he's apologising to her for the annoyance and the delay. So that does it. Two

steps back, up onto the counter, and straight over the grille. I felt like this

once, after Id jumped the fence at the Scoreboard End and just before I started

running across the pitch towards the Stretford End. The clerk calls through to

the main office but I'm already through there to save him the trouble. No, I

don't want to go through into the other office and wait for the manager. I don't

want to go anywhere you can lock me in. You realise you're being very selfish

and annoying all the other people waiting. I don't care. I've been waiting three

weeks and I'm not leaving here till I've seen the manager you think you can just

go on messing people around and they're just going to sit on their arses and

take it well I want my money.

Just as I'm

going out through the hall with everything settled amicably, who should pass me

going in but a bloke in a blue uniform and a tall hat who probably just happened

to be dropping in for a chat. So I take off down Lever Street like a lemming

that's late for the last train to Blackpool.

When I got

home from work that night I went straight to Iry's door. When he opens up

something strange happens to his face. It cracks open like a whale just seen a

big wave. Lights up like a pinball machine, balls rolling and dials whirring

everywhere, never been played for years because there were no coins to fit. "Hey

Iry, have the law been round this afternoon ?"-"No man, they don't come round.

Hee-hee, you was funny. We all have a larf. We can hear you through the walls

and everybody larf."-"They weren't annoyed then ?" "No man, they not annoyed.

They larfing together like they not larfed in years. I been larfing all

afternoon'

We talked for

a while longer, leaning over the parapet. I noted that the sun was larfing too.

It was turning into a fine April evening. Down in the adventure playground, the

kids were crossing fuel-ash oceans and climbing scaffold-tube canyons.

Things soon

came to a head at Hamer's. The following Monday we returned from a wet weekend

to find he wanted us to work down a ten-foot trench with no shoring. It looked

about as safe as Ronan Point. Everybody was muttering and agreeing it was

dangerous, but no one would refuse to go down it. Come tea-break I walked over

to the Precinct and phoned the Factories Inspector. He was there in the time it

took me to walk back. He strolled right around the site before he just happened

to notice the trench. The agent was listening and looking embarrassed, and the

lads were watching and nodding and agreeing that it was about time and it had to

happen sooner or later, and the inspector was telling the agent to claw all the

earth back from the top of the trench with the digger. Everybody must have known

it was me who phoned, but nobody said anything about it. I was annoyed with

myself because it wasn't the way I wanted to do things. I suppose I did it

mainly because I wasn't too struck on being crushed to death, but it was partly

just exasperation too. Little things from the past week that had been building

up, like the channel I was told to pick out so I got covered in muddy water,

when I could have done it a cleaner way. And then it turned out it wasn't a

spring causing the water at all-it was a leaking sewer from our own site toilet.

On the Monday

afternoon we were down the trench filling the muck skip. George was at the top

acting as banksman because the crane-driver couldn't see us down there. And

George kept guiding the skip down to where I could almost reach to unhook it but

not quite. And something started to boil again. I started shouting and swearing

at George, using words I didn't know I knew. Then George offered to knock my

block off and I began to sober up. I suppose it was partly a built-in sense that

you don't get into a fight on the job, and partly that I didn't fancy the idea

of fighting George (there was no glory in it if I won and a bloody nose if I

lost). But mainly, I suddenly realised I'd lost my rag with the wrong bloke at

the wrong time. When you start fighting amongst yourselves, it's time to jack

up-which is what I did.

Being angry's

a bit like laughter-you've got to learn to control it, because it can work two

ways. I was working for Laing's once when we refused to leave the cabin after

tea-break. The contracts manager came in and interrupted the meeting, said he

didn't care how long he waited, it was his cabin and he wasn't moving. So I said

how when I was a little lad I used to play football with a kid who would always

take the ball home when he was losing, because it was his ball. Well for a

moment I had two hundred blokes right there, faces lit up and throats barking.

Even the agent was laughing. Trouble was, when the laughter stopped, we lost out

on the being serious, and all the anger fizzled out in a couple of days.

I don't

really know if there's a science of being angry or being funny, except that when

you see faces lit up, you think may be it's possible for people to be alive till

they're dead. It's a bit like a lighthouse-it doesn't show you much, just keeps

you in with an idea where you're aiming at.

Rick Gwilt

January 1977

|